Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour Volume 1 (2019), Article ID: JMHSB-106

https://doi.org/10.33790/jmhsb1100106Methodology

Acculturation & Attitudes towards Disability for Arab Americans

Tarek Zidan1*, MSW, Ph.D, Keith Chan, MSW, Ph.D2

Assistant Professor, School of Social Work, Indiana University South Bend, Wiekamp Hall, 2217, 1800 Mishawaka Ave, United States.

Assistant Professor, School of Social Welfare University at Albany, 1400 Washington Ave, Albany, NY 12222, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Tarek Zidan, Assistant Professor, School of Social Work, Indiana University South Bend, Wiekamp Hall, 2217, 1800 Mishawaka Ave, United States. E-mail: tzidan@iu.edu

Received date: 29th October, 2019

Accepted date: 10th December, 2019

Published date: 12th December, 2019

Citation: Zidan, T., & Chan, K. (2019). Acculturation & Attitudes towards Disability for Arab Americans. J Ment Health Soc Behav 1: 106.

Copyright: ©2019, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

According to 2010 Census estimates, there are 1.9 million Arab Americans in the United States, although the estimate may be closer to 3.7 million. Arab Americans are one of the fastest growing immigrant groups; over half are foreign-born and come from over 22 different countries. Acculturation is an important construct to consider for Arab Americans, who have a long history of immigration and cultural differences. A systematic literature review was conducted to understand acculturation and attitudes toward persons with disabilities for immigrants and refugees, as they relate to Arab Americans. Using multiple databases (PsycInfo, Ebscohost, Social Science Abstracts, and Google Scholar), we identified 300 articles using the search terms disabilities, acculturation, attitudes and Arab American. Of this number, 90 scholarly articles were chosen that highlighted acculturation and attitudes toward persons with disabilities among minority, immigrant, and refugee groups. The systematic review identified themes regarding acculturation, ethnic identity, social contact with the host culture, and the stigma of disabilities. Findings revealed that ethnic identity, social contact with the U.S. host culture, and the stigma of disability from the country of origin can influence attitudes of Arab Americans towards persons with disabilities.

The systematic review highlighted substantial gaps in the knowledge base and the importance of understanding attitudes of immigrants and refugees towards persons with disabilities within the Arab American community. Further research is needed to examine how the acculturation process can affect attitudes towards disabilities, and where policy and practice can intervene to improve outcomes. Social work practitioners must be culturally sensitive to the distinct aspects of Arab culture and their acculturation process, thereby enhancing their skills in the delivery of services. Results highlight the need for awareness in the struggles of immigrants and refugees, and how they can impact attitudes toward persons with disabilities in Arab American communities.

Key words: Arab Americans, Acculturation, Ethnic Identity, Disability, Attitudes

Acculturation & Attitudes Towards Disability for Arab Americans

According to 2010 Census estimates, there are 1.9 million Arab Americans in the United States (U.S), although the estimate may be closer to 3.7 million [1]. Arab Americans come from over 22 different countries and have a long history of migration. They may embody many different cultures due to their varied immigration pathways from the Middle East, Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia, and to the US. Acculturation is an important construct to consider for Arab Americans because of their multiethnic and multinational migration history.

Acculturation is associated with ethnic identity and a sense of cultural heritage [2,3], which may impact perceptions towards disability for Arab Americans. There is limited research which examines how the acculturation process for Arab Americans may influence attitudes towards persons with disabilities. Insights into this process will raise awareness of how their struggle can impact their attitudes toward persons with disabilities in Arab American communities.

Arab Americans are very heterogeneous in their cultural heritage. Past research on disability for this population has not fully considered their varied ethnic identities and how this may influence their attitudes towards persons with disabilities. Subsequently, their values, beliefs, and attitudes toward persons with disabilities might differ from those held by their American mainstream counter parts, as well as from those Arabs living in the Middle East and elsewhere.

Background

History of Arab Americans

Arab Americans are very diverse in socio-demographic characteristics, acculturation and assimilation [4]. Arab Americans who identify themselves as being of “Arab” descent are among the fastest growing minority groups in America [5]. According to the Arab American National Museum [6], “Arab Americans are diverse in terms of migration to the U.S., and their national religious, educational, and professional background. Despite this diversity, they do share a language and a cultureal heritage that gives them a shared American identity” (p.26).

In the most general terms, the Arab population self-identifies as “the Arab Nation” or “al-Umah al-Arabiya” (in Arabic) because its members speak Arabic and share the values, culture, and traditions inherited from the Arabian Peninsula’s nomadic tribes [2,7,8]. Samhan [9] and Majaj [10] also differentiate between the terms “Arabs” and “Arab Americans.” “Arabs” refer to the people living in one of the Arab countries, while “Arab Americans” refer to Arabs, who immigrated to or were born in the United States, but whose heritage comes from Arab countries. Adding another layer of complexity, there are those who speak Arabic and migrated from Arab countries, such as Kurds in Iraq and Syria, yet culturally are not considered Arabs. Arab Americans live in every state in small towns and large metropolitan cities (e.g., Los Angeles, San Francisco, Detroit, Chicago, Houston, Washington, DC, and New York City) [6,11]. Despite their shared language, religious affiliations, cultural beliefs and traditions, Arabs are very heterogeneous and diverse within their own sub-cultures [2,8,12], yet are an integral and diverse population in American society [13]. For example, Abraham [14] describes the Arab population as embracing “numerous national and regional groups as well as many non-Muslim religious minorities” (para .3). The majority of Arabs are Muslim; however, roughly 10% of them are Christians living in Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Palestine, and, Jordan. In Lebanon, almost 50 percent of the population is Christian and other [11,13]. The majority of Arabs speak Arabic but with different dialects; some Arabs in North Africa speak more French and Spanish than they do Arabic (e.g., Tunisians, Moroccans, and Algerians). Arab Americans differ in the clothing, food [2], and religious affiliation based on country and region of origin. For example, slightly more than half of all Lebanese are Christians, with the rest a mix of Islam and other religions. In the 2012 report by AAI, Arab American ancestry represents about 22 Arabicspeaking countries in North Africa and in the Southwestern Asia such asLebanon (26%), Egypt (10%), Syria (8%), Somalia (6%), Morocco (5%), Palestine (5%), Iraq (5%), Syrian/Chaldean (5%), Jordan (3%), and Sudan (2%). Some others do not like to be called by their countries, but rather prefer to classify themselves as Arabs (15%). Additionally, 11% come from Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Kuwait, Libya, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen [1]. Many Arabs may have migrated through Europe and other non-Arab countries before arriving to the US.Michigan, specifically the Detroit-Dearborn area (Wayne County), has the largest and most diverse Arab American population, the greatest immigrating from Syria and Lebanon [4]. Zogby’s [15] poll estimates that this population is highly concentrated in Detroit- Dearborn (more than 400,000), Los Angeles (over 300,000), and New York City (at least 225,000).

Immigration of Arab Americans

Prior to the 1940s, the U.S. government used racial schemas to determine eligibility for citizenship and naturalization. During this period, immigrants were not able to become citizens if they were not legally determined to be “white.” Thus, Arab Americans were classified as both white and non-white, dependent upon court decisions. After the 1940s, the U.S. government identified Arabs from North Africa as “white” and from all other Arab countries as “black or others” [15].

Literature on Arab Americans has shown that this immigrant group arrived during several immigration pattern waves with some asa part of the slave trade from 1700 to 1890 [6]. The first wave of Arab immigrants arrived between 1890 and 1920. The second wave was between 1948 and 1966, and the majority of Arabs were Palestinian, Egyptian, Syrian, and Iraqi. By the 1970s, the third wave of Arab Americans found it more difficult to integrate into American society due to political conflicts such as the 1967 Arab-Israeli war and the tragic events of September 11, 2001. The largest group of immigrants came after the Iran-Iraq War and the First Gulf War. Many exhibited a high level of isolation due to the post 9/11 backlash [11,16]. The geopolitical divide between the Arab world and the United States has affected Arab immigrants in each wave of arrival [17], leading to struggles with assimilation. Due to a multitude of factors in the political and economic relationships between the U.S. and the Arab world, their history of Arab Americans in the US is very complex [16].

Arab Americans & Muslim Americans

In the literature, “Arab American” has been used interchangeably with the name “Middle Easterns” [18]. However, “Arab Americans” are different from “Muslim Americans” in that Arab Americans are identified by ethnic origin while Muslim Americans are identified by religious affiliation. Nevertheless, Islam is the main religion within Arab countries [19]. There is considerable overlap in the literature and public understanding with regard to the Arab and Muslim groups. The majority (77%) of Arab Americans are Christians (mostly Catholics, then Eastern Orthodox, and Protestants) and only about 23% are Muslim (mostly Sunni, then Shia, and Druze; [20,21]). Yet, it is important to note that not all Arabs are Muslim and not all Muslims are Arab [22]. For example, the majority of Iranians and Iranian Americans are Muslim but do not speak Arabic and have no Arab ancestry [2].

Arab Americans are highly heterogeneousin their ethnic heritage, country of origin, pre-migration factors, post-migration circumstances, and religious beliefs. This is reflected in differences in educational background and labor participation for this population.

Education and Labor Participation of Arab Americans

According to the AANM [6] & Abu-Ras and Abu-Bader [20], about 40% of Arab Americans hold bachelor’s degrees and more than 24% hold graduate degrees. This is compared to 17% and 9%, respectively, of the general U.S. population. The majority of Arabs born in the U.S. have high school diplomas, whereas those born in Arab countries are more likely to have college degrees [23]. Arab Americans are younger than other major ethnic groups as well as the U.S. population primarily in the 20–44 age groups with 47% under the age of 25 and only 6% who are 65 years or older.

Similar to the national average in labor force, about 64% of Arab American adults are employed and 10% unemployed [1]. The most recent U.S. Census data 5-year report based on the American Community Survey (ACS) estimates that the median household income annually in 2010 for Arab Americans was ($56,000), which is higher than the median household income ($51,914) for all households in the U.S. [24].

Acculturation of Arab Americans

According to Amer [2], acculturation is a cultural change process between two groups in which a single group or both groups adopt each other’s beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. Acculturation occurs from the experience of exposure to a different culture. Berry [25] describes acculturation as the process of adapting to a new culture that is different from one’s own. Haboush [26] adds that the person’s own culture is influenced by the dominant culture in the community where they are exposed. Erickson et al. [27] suggest that acculturation begins when new immigrants arrive in the new country, after which they either accept or reject all or parts of their own culture and the dominant culture and establish an integrated cultural identity. Ortiz et al. [28] posit that mainstream U.S. culture is a mixture of Western European culture and the individuals’ own culture. Ward and Geeraert highlight that acculturation is affected by family, work, school, and socio-political contexts. Furthermore, Khawaja [29] suggests that discrimination may play an important role in the acculturation of immigrants who immigrate from countries in the Muslim world. According to Al-Krenawi et al. [30], “ethnic Arab societies are highly diverse and consist of heterogeneous systems of social differentiation based on ethnic, linguistic, sectarian, familial, tribal, regional, socioeconomic, and national identities” (Para.6). Arab Americans were developed by immigration patterns of the Arab immigrants who moved to the Western countries. Acculturation patterns of Arab immigrants were influenced considerably by mainstream American culture. Al-Krenawi and Graham add that factors such as age, religious affiliation, visiting the homeland Arab country, and length of stay in the host country will determine the level of acculturation of Arabs living the Western countries. The theory of acculturation broadens the study’s scope of Arab population’s attitudes toward disabilities from the address on acculturation.

Acculturation Theory

Although acculturation theory was first established by anthropologists, it has become very significant in the field of cross-cultural studies since the 1900s [2,25,31]. This theory refers to changes in an individual’s attitudes, behavior, and values based on the belief that social activities are the result of acculturative contact with another culture [32]. According to Amer [2], the term “acculturation” highlights the nature of cultural interaction between two groups (new/acculturation group and host group) and the changes that may occur through direct and indirect contact with each other. Amer [2] also indicates that acculturation is used interchangeably with assimilation in the literature. These changes are part of adapting to the dominant (or host) group’s cultural beliefs, values, and behavioral customs. These changes may affect, either positively or negatively, the acculturation group’s attitudes and behaviors toward other people and, more specifically, toward the mentally ill. During this acculturation process, the new group will either assimilate or dissimilate into the adopted host culture [2,31,33].

According to Graves [34], there is a distinction between general acculturation and psychological acculturation [2]. He points out that general acculturation refers to the changes in new group’s value system and cultural practices that it has adapted from the host group; whereas, psychological acculturation refers to “the intra-individual processes whereby a single person changes his or her attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors after exposure to an alternative culture” (p.6). This latter process can be either positive or negative. A positive psychological adaptation may occur when there is a good fit (goodness of fit) between the person and the host culture, one that leads to more positive attitudes and behaviors toward mental health. However, negative adaptation may occur when there is conflict and identity confusion between the person and the host culture[2,31,34].

Several theorists have emphasized the acculturation model that occurs through a linear assimilation or a unidimensional acculturation [2,32,33]. The acculturation model is based on the length of stay in the host culture, which includes a period of biculturalism as the midpoint of the process before full assimilation into the host culture. In contrast, [36,37] favor the bi-dimensional and multidimensional models of acculturation. The first is based on the person’s ethnic identity theory and assimilation process, which may occur through adopting the host culture while retaining one’s ethnic culture. Adaptation and retentiondepend on a variety of factors, such as the quantity and quality of the original culture’s traditions and community support from others with the same cultural background. The well-known multi dimensional model developed by Berry [37] is also based on the person’s ethnic identity theory; it further explains that individual decisions are made at the level of acculturative contact with others in the new host culture [2].

According to Amer [2], this multi-dimensional model has gained more recognition and support in recent years. Researchers have agreed that sociodemographic and other variables significantly influence the acculturative process, along with the quality and quantity of the contact with others from either the original or the host culture. In addition, acculturation significantly affects people’s attitudes and behavior toward others, especially among immigrants and minorities.

Acculturation and Perceptions Towards Disability

The influence of acculturation and cultural differences on attitudes toward persons with disability has substantial practical implications. Thus, understanding cultural differences in this context is crucial for such a diverse country as the United States [38]. According to Mio et al. [3], the process of acculturation is an important factor in shaping people’s attitudes and beliefs toward others, including those with disabilities. Mio et al. also defined acculturation as the experiences and changes that occur to individuals and groups through their interactions and contacts with people from a different culture. People from other countries and ethnic groups often struggle to acculturate themselves to the host culture while maintaining their own cultures [39]. Acculturation is also linked to the concept of ethnic identity. People that have a strong sense of cultural heritage and ethnic identity have greater difficulty with the acculturation process than those who do not self-identify as closely with their native heritage [3]. For example, some Arabs may strongly identify with their native culture and thus reject mainstream U.S. culture as a host culture (separationist); whereas, others may choose to integrate into both the Arab and American cultures (integrationist) or not belong to either culture (marginalist). Then, there are those who reject their native Arab culture and merge themselves into the host culture (assimilationist). People’s attitudes are influenced by their levels of assimilation and acculturation with the new or host culture [3,40]. Thus, Arab Americans with a strong sense of ethnic identity will likely struggle with adopting Western culture and U.S. views regarding people with disabilities.

Research has examined acculturation and its effect on attitudes toward persons with disabilities [41]. For example, a cross-cultural study of Asian students, investigating attitudes toward persons with disabilities found that anxiety was associated with negative attitude towards persons with disabilities, while longer lengths of stay in the U.S. is associated with positive attitudes. Additionally, a comparison of attitudes of Greek citizens and Greek Americans toward persons with disabilities found that Greek Americans hold more positive attitudes toward the disabled population than Greek citizens. This is likely due to the attached stigma of disability in Greek society, reporting that Greeks are more likely to feel ashamed about disabled family members and try to hide them from others. On the other hand, Greek Americans, hold higher positivity attitudes from assimilation and acculturation of the American societal values [42]. The researchers also concluded that previous contacts with disabled people positively influenced the participants’ attitudes.

Similarly, Choi et al. [43] provides that Korean Americans have more positive attitudes toward persons with mental disabilities than their Korean counterparts. One explanation for the difference is more stigmatization of persons who suffer from mental disabilities in Korea than in the United States. Another reason is Korean’s cultural belief that mental illness is a punishment for having committed an evil act. On the flip side, Korean Americans reportedly hold more favorable attitudes toward persons with disabilities due to their higher levels of acculturation.

However, findings on the impact of acculturation on attitudes towards persons with disabilities bears inconsitency. A study comparing Chinese international students and Chinese graduates in China reveals no significant difference in attitudes toward persons with intellectual disabilities [41]. The research suggests that Chinese international students face language barriers during the acculturation process, which likely decrease attitudinal change towards persons with disabilities. In addition, positive changes in Chinese legislative policies for people with disabilities in recent years may also lead to more favorable attitudes of Chinese graduates; In essence, the study indicated no statistical difference in attitudes between Chinese international students and students in China. An extension of research, using meta-analysis, examining acculturation and attitudes, as related to disabilities among the Arab American population, can increase the current knowledge.

Methods

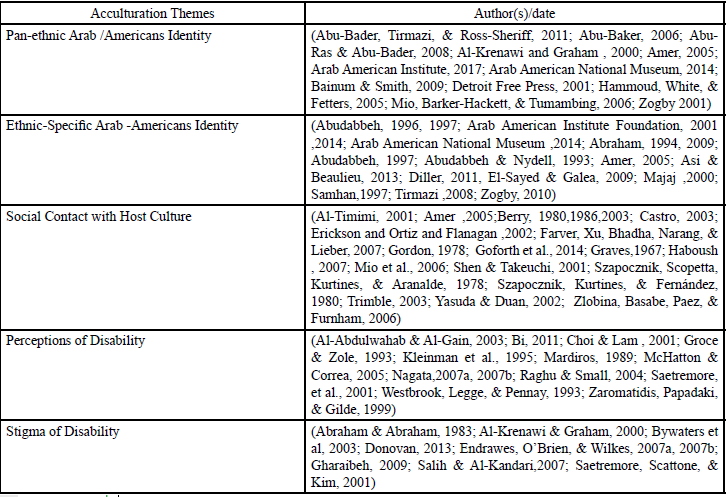

A systematic literature review was conducted to understand acculturation and attitudes toward persons with disabilities for immigrants and refugees, as they relate to Arab Americans. Using multiple databases (PsycInfo, Ebscohost, Social Science Abstracts, and Google Scholar), we identified 300 articles using the search terms disabilities, acculturation, attitudes and Arab American. Of this number, 90 scholarly articles were chosen that highlighted acculturation and attitudes toward persons with disabilities among minority, immigrant, and refugee groups. The systematic review revealed three key themes 1) Acculturation & Ethnic Identity, 2) Social Contact with Host Culture, and 3) Stigma of Disabilities (Table 1).

Acculturation & Ethnic Identity

Through a systematic review of literature, the prevailing acculturation model shows the greatest explanatory power with acculturation with Arab Americans based on two principles: 1) cultural maintenance (marginalization & separation), where a person maintains his/her own culture identity through restricted exposure to the host culture, and 2) contact participation (assimilation & integration), where a person chooses to participate and be part of the larger host society. Arab Americans may also move toward four different modes of acculturation: 1) assimilation, 2) separation, 3) integration, and 4) marginalization. The Arab American community as a whole may choose to separate itself from the host mainstream American culture and value its own Arab heritage culture, even if some of its individual members may choose to fully integrate into the mainstream culture. This theoretical model also accounts for how the host culture may marginalize and/or isolate individual Arab Americans or their community from the mainstream culture due to Islamophobia. Integration, on the other hand, occurs when an individual or a community maintains its ethnic cultural identity while simultaneously choosing to transition into a host culture and become bi-cultural, to become an integral part of the larger society. Acculturation is a continuing process, and each mode of acculturation may influence attitudes toward persons with disabilities. Past research suggested that Arab Americans who identified strongly with mainstream American culture had more favorable attitudes toward persons with disabilities, and embraced attitudes of optimism–humanism, behavioral–misconceptions, and pessimism–hopelessness, regardless of their level of identification with Arab culture.

In this meta-analysis study, Arab Americans’ level of identification with mainstream American culture was stronger than previous studies of Arab Americans [2,44]. However, those who self-identified with the general Arab-Muslim heritage culture had a high level of separation from mainstream American culture. Arab Americans who identify strongly with mainstream American culture seemed more likely to have favorable attitudes toward persons with developmental disabilities [3,40], and that acculturation is linked to a person’s ethnic identity and is an important factor in shaping people’s attitudes and beliefs toward others [2]. Acculturation was defined in the scholarship as the experiences and changes that occur to individuals and groups through their interactions and contacts with people from different cultures. This process can be influenced by how strongly one is tied to one’s ethnic identity. Tirmazi [45] suggested that in addition to SED factors, various ecological (environmental) factors (e.g., ethnic language use, religiosity, family cohesion, and social support) could influence the level of acculturation among Arab- Muslim Americans. For example, based on Berry’s [46] model of acculturation (i.e., integration, assimilation, separation, and marginalization) and as discussed in the theory section, Arabs in America will go through four distinct stages of acculturation, the end result of which will be (a) a strong identification with their ancestral culture and subsequent rejection of (separation from) mainstream American culture (host culture), (b) integration into both cultures (integration), (c) not belonging to either culture (marginalization), and (d) rejection of their ancestral Arab culture and merging into mainstream American society (assimilation). In the Tirmazi study, Arab Americans’ attitudes were shown to be influenced by their high levels of assimilation and acculturation into mainstream American culture.

Social Contact with the Host Culture

Research suggested that the length of stay in mainstream American culture (host culture) is associated with higher levels of acculturation and assimilation [2]. Accordingly, Arab Americans who have lived here longer are more likely to report a higher degree of interaction with mainstream American culture than those who only interacted with it for a short period of time [47,48]. Likewise, studies have found a positive association between sociodemographic variables (e.g., education and income) and levels of acculturation [2,31,49], and positive attitudes toward persons with disabilities. In other words, better-educated and wealthier Arab Americans would likely be more integrated into American society due to their jobs, services, and interaction with non-Arabs as well as persons with disabilities. Ethnic identity and social contact with the US host culture can be important components in the acculturation process for Arab Americans. Although there is a growing body of research on attitudes towards Arab Americans, scholarship on Arab Americans’ attitudes towards disability are very limited. Overall, there are substantial gaps in the knowledge base on the relationship of acculturation and disability for Arab Americans.

Stigma Towards Persons with Disabilities

In the Arab world, disability (i’aqa in Arabic) is a generic term that is equivalent to handicapped or retarded in English, and is used to stigmatize persons with disabilities [50,51]. Gharaibeh [51] also suggested that it used to stigmatize such people based on the particular disability and that people with one or more developmental or intellectual disabilities, or a mental illness, are more stigmatized than those with physical or visual impairments are. The attitudes of Arab Americans toward persons with disabilities remain largely unknown. Arab Americans with disabilities also go largely unseen. This lack of visibility has led some researchers to characterize them as an invisible or a hidden minority [52]. However, they became a very visible group due to the backlash against the Arab/Muslim community after the tragedy of 9/11. Social work practitioners need this substantive knowledge so they can better understand and work with the Arab American population. Though the literature on Arab people in Western countries is disparate, investigating the complexities of Arab culture can inform social work practice. This knowledge can help develop culturally appropriate interventions to overcome the stigma toward mentally ill clients [30].

A qualitative study by Endrawes et al. [53] used the phenomenology approach to explore the beliefs, values, and perceptions of Egyptian families in Australia toward relatives who were mentally ill. Researchers collected data using in-depth audiotaped interviews of seven Egyptian families. Most of the families believed that the stigma associated with mental illness prevented their loved ones from seeking treatment. The authors suggested that Arab families may tend to hide mentally ill family members because they fear their families’ reputations will suffer if such knowledge leaks out. These feelings of shame and embarrassment were due to stigma as well as feelings of having “bad” blood or bad spirits inherited from generation to generation. The study concluded that Middle Easterners, including Egyptians, may believe that the cause of mental illness is due to possession by an evil spirit.

For example, underdeveloped rural communities in Egypt follow folk beliefs and practices such as the Zar cult, which is a kind of spiritual healing practice. The term “Zar” translates as a “crazy party” in Arabic, referring to evil spirits [54]. This folkloric or ritual practice has little to do with religious belief. The Egyptian government has outlawed it, but it continues there and in other Arab and African countries. Normally, people do not report such events to the authorities [54].

Among people of different faiths there are also varying attitudes toward people with disability. A comparative study of Arab and Jewish families in Israel with disabled family members found that most Arab participants had experienced more shame and embarrassment than their Jewish counterparts [55]. Another comparison study discussed attitudes toward disabilities between Pakistani and Bangladeshi Muslim parents of disabled children in the United Kingdom. Both groups expressed feelings of shame and negative attitudes toward their children with disabilities [56]. The study also suggested that Muslim families believed that everything in life is under God’s control and depends on “God’s will” or “Allah’s wish” (i.e., “Insha Allah”) [56]. Therefore, a Muslim child or adult with developmental disabilities is viewed as either God’s punishment or as God’s gift. However, the study found little evidence to support the claim that religious beliefs can shape Muslim families’ attitudes toward persons with disabilities [56].

Salih and Al-Kandari [56] conducted a quasi-experimental design to compare two groups of female social work students who took a course about social work and people with disabilities at Kuwait University. The study investigated whether attitudes among students toward persons with intellectual disabilities would be improved by the information provided in the social work course. The experimental group included 31 students and the control group included 30 students who completed the self-administrated Mental Retardation Attitudes Inventory adapted by the authors for the Kuwaiti culture. A pre-test, post-test, multivariate analysis of covariance and a t-test were conducted to compare the significant mean differences between the two groups. The results showed that the course had no effect on students’ attitudes toward persons with intellectual disabilities. The researchers concluded that students’ prior knowledge and information about disabilities influenced their attitudes toward persons with disabilities.

The attitudes toward persons with disabilities in the Arab world have been understudied with the exception of a handful of studies. For example, Al-Abdulwahab and Al-Gain [58] conducted a study in Saudi Arabia and Nagata [59] completed research in Jordan. Both studies examined the attitudes of non-disabled adults and the attitudes of health care professionals toward persons with disabilities. These studies were conducted within the same Arab culture butyielded different results.Specifically, Al-Abdulwahab and Al-Gain [58] found health care professionals’ attitudes more positive while Nagata [59] found the overall attitudes of more negative.

Another study by Nagata [60] examined the attitudes of 94 university students toward persons with disabilities, particularly those with an intellectual disability and a mental illness in Lebanon. The study aimed to determine the baseline of prejudicial attitudes against persons with disabilities and to examine the relationship between the students’ attitudes and their previous personal experience with the disabled. A baseline survey was developed for the study, which examined students’ attitudes toward persons with disabilities. The study showed that the majority of Lebanese students had less favorable attitudes toward people with an intellectual disability, a mental illness or a history of mental illness. Nagata [60] concluded that knowledge and social interaction variables could foster positive public attitudes in Lebanon. Arab Americans are very heterogeneous in their values, beliefs, and attitudes. Moreover, their values, beliefs and attitudes toward persons with disabilities might differ from those held by their American mainstream counter parts as well as from those Arabs living in the Middle East and elsewhere. This study attempts to fill this gap in the literature and explain factors that contribute to Arab Americans’ attitudes (positive or negative) toward persons with disabilities.

Conclusion

The relevant literature indicates that many researchers have studied and discussed the experience of various ethnic groups with regard to their attitudes toward people with disabilities (i.e., African Americans, Chinese Americans, Japanese Americans, Korean Americans, Latin Americans, Native Americans, and Vietnamese Americans; [30,55,61-66]. However, there are a few studies that address attitudes toward persons with disabilities among Arabs in the Middle East, but not in the United States among Arab Americans. The literature demonstrates that attitudes toward people with disability are influenced by sociodemographic variables, level of acculturation, and level of social contact. These variables are the most frequently documented factors in the literature that influence attitudes toward persons with disabilities.

Implications

The systematic review highlighted the importance of understanding attitudes of immigrants and refugees toward persons with disabilities, particularly within the Arab American community. Further research is needed to examine how the acculturation process can influence attitudes towards disabilities, and where policy and practice can intervene to improve outcomes. Social work practitioners must be culturally sensitive to the distinct aspects of Arab culture and their acculturation process enhancing social work professional skills thereby improving the delivery of services for the growing Arab American population. Finally, results also highlight the need to raise awareness in the struggles of immigrants and refugees, and how these struggles can impact attitudes toward persons with disabilities in Arab American communities.

Conflicts of Interest (COI) Statement

The author has declared no conflict of interest.

References

Arab American Institute Foundation. (2017). Demographics.View

Amer, M. M. (2005). Arab American mental health in the post September 11 era: Acculturation, coping, and stress (Doctoral dissertation) University of Toledo.View

Mio, J. S., Barker-Hackett, L., & Tumambing, J. (2006). Multicultural psychology: Understanding our diverse communities. Boston, MA: McGraw Hill.

Hassoun, R. J. (2005). Arab Americans in Michigan. MUSE Project.View

Arab American Institute Foundation. (2014 ). Lobbying for a “MENA” category on U.S. Census.View

Arab American National Museum (AANM). (2014). Arab Americans an integral part of American society. AANM Educational Series.View

Abudabbeh, N. (1996). Arab families. In M. McGoldrick, J. Giordano, & J. K. Pearce (Eds.), Ethnicity and family therapy (2nd ed., pp. 333–346). New York, NY: Guilford Press.View

Abudabbeh, N. (1997). Counseling Arab-American families.In U. P. Gielen& A. L. Comunian (Eds.), The family and family therapy: An international perspective (pp.115–126). Trieste, Italy: Edizioni LINT.View

Samhan, H. H. (1997). Not quite white: Race classification and the Arab Americans experience. In M. Suleiman (Ed.), Arabs in America: Building a new future (pp. 209–226). Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Majaj, L. S. (2000). Arab Americans and the meaning of race. In A. Singh & P. Schmidt (Eds.), Postcolonial theory and the United States: Race, ethnicity, and literature (pp. 320–337). Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

El-Sayed, A., & Galea, S. (2009). The health of Arab-Americans living in the United States: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Public Health,9(1), 272. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-272. View

Abudabbeh, N., & Nydell, M.K. (1993). Transcultural counseling and Arab Americans. In J. McFadden (Ed.), Transcultural counseling: Bilateral and international perspectives (pp. 261– 284). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.View

Abraham, N. (1994). Anti-Arab racism and violence in the United States. In E. McCarus (Ed.), The development of Arab- American identity (pp. 1-232). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Abraham, N. (2009). Countries and their cultures: Arab Americans.View

Zogby, J. (2010). Arab voices: What they are saying to us, and why it matters. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan Ltd.

Diller, J.V. (2011). Cultural diversity: A primer for the human services (4th ed.). Belmont: CA. Brooks/Cole Press.

Abu-Baker, K. (2006). Working with Arab and Muslim American clients. In J. V. Diller (Ed.), Cultural diversity: A primer for the human services (pp.289–301). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole Press.

Detroit Free Press (2001, May 4). 100 questions & answers about Arab Americans: Who are the Arab Americans? View

Hammoud, M. M., White, C., & Fetters, M. (2005). Opening cultural doors: Providing culturally sensitive healthcare to Arab American and American Muslim patients. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 193(4), 1307–1311. doi:10.1016/j. ajog.2005.06.06 View

Abu-Ras, W., & Abu-Bader, S. (2008). The Impact of the September 11, 2001, attacks on the well-being of Arab Americans in New York City. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 3, 217–239. doi:10.1080/1556490080248763.

Zogby, J. (2001). What ethnic Americans really think: The Zogby culture polls. Washington, DC: Zogby International.View

Bainum, B., & Smith, R.A. (2009, January 9). Report on Middle Eastern Americans and disabled persons. Academic Commons Columbia University online Journal.View

Arab American Institute Foundation. (2001). Arab Americans today: Family and settlement patterns.View

Asi, M., & Beaulieu, D. (2013). Arab households in the United States: 2006–2010: American community survey briefs. U.S. Census Bureau.View

Berry, J. W. (2003). Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In K. M. Chun, P. E. Balls Organista, & G. E. Marín (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 1–260). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. View

Haboush, K. L. (2007). Working with Arab American families: Culturally competent practice for school phycologists. Psychology in the Schools, 44(2), 183–198. doi: 10.1002/ pits.20215 View

Erickson, C. D., & Al-Timimi, N. R. (2001). Providing mental health services to Arab Americans: Recommendations and considerations. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 7(4), 308–327.View

Ortiz, S. O., & Flanagan, D. P. (2002). Best practices in working with culturally diverse children and families. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology: IV (pp. 337–352). Bethesda, MD: Author.View

Khawaja, N. G. (2016). Acculturation of the Muslims Settled in the West. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 10(1). http://dx.doi. org/10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0010.102 View

Al-Krenawi, A., & Graham, J.R. (2000). Culturally sensitive social work practice with Arab clients in mental health settings. Health & Social Work, 25(1), 9–23.View

Castro, V.S. (2003). Acculturation and psychological adaptation. Westport, CN:Greenwood Press.View

Gordon, M. (1978).Human nature, class, and ethnicity. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Szapocznik, J., Scopetta, M., Kurtines, W., &Aranalde, M. (1978). Theory and measurement of acculturation. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 12(2), 113–130.

Trimble, J. E. (2003). Introduction: Social change and acculturation. In K. M. Chun, P. E. Balls Organista, & G. E. Marín, (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research(pp. 3–13).Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Graves, T.D. (1967). Psychological acculturation in a tri-ethnic community: Southwestern. Journal of Anthropology, 23, 336– 350.

Szapocznik, J., Kurtines, W. M., & Fernández, T. (1980). Bicultural involvement and adjustment in Hispanic-American youths. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 4 (3), 353–365.View

Berry, J. W. (1980). Acculturation as varieties of adaptation. In P. Padilla (Ed.), Acculturation, models and some findings (pp. 9–25). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Westbrook, M., Legge, V., &Pennay, M. (1993). Attitudes towards disabilities in a multicultural society. Social Science & Medicine, 36(5), 615–623.View

Yasuda, T. & Duan, C. (2002). Ethnic identity, acculturation, and emotional well-being among Asian American and Asian international students. Asian Journal of Counseling, 9(1), 1–26.View

Farver, J. A., Xu, Y., Bhadha, B. R., Narang, S., & Lieber, E. (2007). Ethnic identity, acculturation, parenting beliefs, and adolescent adjustment: A comparison of Asian Indian and European American families. Merril-Palmer Quarterly, 53, 184–215.View

Bi, H. (2011, May). Chinese graduate students’ attitudes toward persons with intellectual disabilities: An acculturation approach. Paper presented at the 55th Annual Conference of the Comparative & International Education Society (CIES), Montreal, Canada.View

Zaromatidis, K., Papadaki, A., &Gilde, A. (1999). A crosscultural comparison of attitudes toward persons with disabilities: Greeks and Greek-Americans. Psychological Reports, 84(3c), 1189–1196.View

Choi, G. H., & Lam, C. S. (2001). Korean students’ differential attitudes toward people with disabilities: An acculturation perspective. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 24(1), 79–81.View

Abu-Bader, S. H., Tirmazi, M. T., & Ross-Sheriff, F. (2011). The impact of acculturation on depression among older Muslim immigrants in the United States. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 54(4), 425–448. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2011.560928 View

Tirmazi, M. T (2008).The Impact of Acculturation on Psychosocial Well-being Among Immigrant Muslim Youth (Doctoral dissertation).Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. (Accession Order No. 3307125).

Berry, J. W. (1986). The acculturation process and refugee behavior.In C. L. Williams, & J. Westinmeyer (Eds.), Refugee mental health in resettlement countries (pp. 25–37). Washington, DC: Hemisphere.

Goforth, A. N., Oka, E. R., Leong, F. T., & Denis, D. J. (2014). Acculturation, acculturative stress, religiosity and psychological adjustment among Muslim Arab American adolescents. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 8(2). http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/ jmmh.10381607.0008.202 View

Zlobina, A., Basabe, N., Paez, D., & Furnham, A. (2006). Sociocultural adjustment of immigrants: Universal and groupspecific predictors. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30, 195–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.005 View

Shen, B. J., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2001). A structural model of acculturation and mental health status among Chinese Americans. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 387–418. doi: 10.1023/A:1010338413293 View

Donovan, E. A. (2013). Arab Americans parents’ experience of special education and disability: A phenomenological exploration (Doctoral dissertation). View

Gharaibeh, N. (2009). Disability in Arab societies. In C. A. Marshall, E. Kendall, M. E. Banks, & R. M. S. Gover (Eds.), Disabilities: Insights from across fields and around the world (Vols. 1–3) (pp. 63–79). Westport, CT: Praeger. View

Abraham, S. Y., & Abraham, N. (1983).Arabs in the new world: Studies on Arab-American communities(1st ed.). Detroit, MI: Wayne State University, Center for Urban Studies.

Endrawes, G., O'Brien, L., & Wilkes, L. (2007a). Egyptian families caring for a relative with mental illness: A hermeneutic study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 16(6), 431–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2007.00498 View

Endrawes, G., O’Brien, L., & Wilkes, L. (2007b). Mental illness and Egyptian families.International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 16(3), 178–187. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0349.2007.00465 View

Saetremore, C. L., Scattone, D., & Kim, K. H. (2001).Ethnicity and the stigma of disabilities.Psychology & Health, 16(6), 699– 713. doi: 10.1080/08870440108405868 View

Bywaters, P., Ali, Z., Fazil, Q., Wallace, L.M., & Sing, G. (2003). Attitudes towards disability among Pakistani and Bangladeshi parents of disabled children in the UK: Consideration for services providers and the disability movement. Health and Social Care in the Community, 11(6), 502–509. View

Salih, F. A., & Al-Kandari, H. Y. (2007). Effect of a disability course on prospective educators’ attitudes toward individuals with mental retardation. Digest of Middle East Studies, 16(1), 12–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1949-3606.2007.tb00062 View

Al-Abdulwahab, S. S., & Al-Gain, S. I. (2003). Attitudes of Saudi Arabia care professionals towards people with physical disabilities. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal,14(1), 63–70. View

Nagata.K. K. (2007b). The scale of attitudes towards disabled persons (SADP): Cross-cultural validation in a middle income Arab Country, Jordan. The Review of Disability Studies: An International Journal,3(4),3–9. View

Nagata, K. K. (2007a). The measurement of the Hong Kongbased “baseline survey of students” attitudes toward people with a disability: Cross-cultural validation in Lebanon. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 30(3), 239–241. View

Groce, N., & Zola, I. (1993).Multiculturalism, chronic illness, and disability. Pediatrics, 91(5), 1048-1055. View

Kleinman, A., Wang, W. Z., Li, S., Cheng, X. M., Dai, X. Y., Li, K. T., & Kleinman, J. (1995). The social course of epilepsy: Chronic illness as social experience in interior china. Social Science & Medicine, 40(10), 1319–1330. View

Mardiros, M. (1989).Conception of childhood disabilities among Mexican-American parents.Medical Anthropology, 12(1), 55–68. View

McHatton, P. A., & Correa, V. (2005). Stigma and discrimination: Perspectives from Mexican and Puerto Rican mothers of children with special needs. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 25, 131–142. View

Raghu, R., & Small, N. (2004). Cultural diversity and intellectual disability.Current Opinions in Psychiatry, 17(5), 371–375. View