Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour Volume 2 (2020), Article ID: JMHSB-125

https://doi.org/10.33790/jmhsb1100125Mini Review

Gender Differences in Depression Literacy Among African American Young Adults

Maureen Wimsatt, Ph.D., M.S.W1, Kim L. Stansbury, M.S.W, Ph.D2*., Gaynell M. Simpson, Ph.D., LCSW (GA)3, Yarneccia D. Dyson, M.S.W., Ph.D4., Kristin W. Bolton, Ph.D., M.S.W5., Rhonda Brown MSW 6

1Development Director, Sacramento Native American Health Center, Sacramento, CA, United States.

2Associate Professor, School of Social Work, North Carolina State University. Raleigh, NC., United States.

3PT Instructor, Georgia State University, School of Social Work. Atlanta, GA., United States.

4Assistant Professor, Department of Social Work, University of North Carolina-Greensboro. Greensboro, NC., United States.,United States.

5Associate Professor, University of North Carolina-Wilmington. Willington, NC. United States.

6MSW Student at the joint University of North Carolina-Greensboro/North Carolina Agriculture and Technical State University MSW Program. Greensboro, NC. United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Kim L. Stansbury, M.S.W, Ph.D., Associate Professor, School of Social Work, North Carolina State University. Raleigh, NC., USA. E-mail: klstansb@ncsu.edu

Received date: 06th August, 2020

Accepted date: 22nd September, 2020

Published date:25th September, 2020

Citation: Wimsatt, M., Stansbury, K.L., Simpson, G.M., Dyson, Y.D., Bolton, K.W., & Brown, R. (2020). Gender Differences in Depression Literacy Among African American Young Adults. J Ment Health Soc Behav 2(2):125. https://doi.org/10.33790/ jmhsb1100125

Copyright: ©2020, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

This pilot study used a coping framework to explore gender differences in depression literacy among African American young adults. A total of 38female and 15 maleyoung adults read a vignette about an individual with depression; completed a mixed-methods survey about what may be wrong with the person; identified strategies for coping with the issue; and reported the individual’s prognosis with and without professional help. Analysessuggested gender differences in perceived depression and recommended coping strategies. Varied response patterns were also associated with the gender of the individual in the vignette. Implications of examining depression literacy through a gender-focused coping framework are discussed..

Keywords:

Depression literacy, Coping, Gender Differences, African Americans, Young Adulthood

Introduction

Young adulthood is marked by increased independence and changes in contextual and social roles [1-4]. During this period, young adults become more individualistic and begin to define their life purpose [5-7]. Young adulthood is also denoted by increased geographic mobility; pursuit of diverse opportunities; and completion of developmental milestones, including personal and professional goals [4,8-10]. Due to the multiplicity and complexity of these changes, young adulthood is associated with greater mental health risks than later developmental stages [11-13]. Given that the manifestation of depression is common during this period, and research suggests that depression rates increase in a linear fashion as adolescents transition into adulthood [11,12,14], it is important to consider the depressive symptoms as they present during adolescence. It is estimated that 15% of adolescents experience depression, and the prevalence rises to greater than 20% among young adults over the age of twenty [14-16].

In 2015, approximately 3 million American youth between the ages of 12 and 17 had at least one major depressive episode during the previous year. This represented 12.5% of the U.S. population aged 12 to 17. Furthermore, extant research has documented gender differences in depression rates [17,18]. Gender-related disparities begin to emerge during adolescence, with post-pubescent females being twice as likely to be depressed as their male counterparts [19-21]. Young adult African American women may be especially affected by depression. Recent empirical findings reveal African American females experience more severe and chronic depression than men or Caucasian women [22],[23]. However, mistrust of the mental health system often results in underreporting of depression among African Americans [24]; therefore, we know little about the depression experiences of young adults from the African American community.

Gender variations in depression are often attributed to sexdifferentiated coping resources and strategies [21,25-27]. Coping, or the extent to which an individual can manage emotions in accordance with the stressful demands of their environment, can influence one’s risk of developing depression [18,25,28-30]. Males often believe they have more psychological and physical resources to cope with the environment and use problem-focused coping strategies (e.g., planning and active coping) to eliminate external demands. In contrast, females frequently view themselves as lacking the resources to cope with demands, and they use emotion-focused strategies (e.g., rumination, distraction) to moderate stressors in the environment [26,27,30-33]. Individuals experience a greater number of depressive symptoms when they perceive themselves as having limited coping resources and/or if they use emotion-focused coping strategies more often than problem-focused ones. Thus, it is argued that the presence of differnces in coping processes between males and females leaves females at higher risk for developing depression [32-34]. However, there is a paucity of research on African American young adults that captures their literacy of depression and possible sex-differentiated in coping strategies.

Purpose

There is an inherent need to explore the impact of gender differences on individual level factors such as gender at the intersection of understanding depression and other mental health diagnosis among African American young adults in the United States. This study offers a preliminary investigation of the relationship between gender, coping and depression. Specifically, the goal of the present study is to investigate depression literacy in a sample of African American young adults. Furthermore, this study seeks to to expand upon previous research, applying gender-focused coping framework to the exploration of depression literacy in African American young adults. Compared to African American young adult males, the hypotheses are that African American young adult females would: (1) be more depression literate; (2) label fewer mental health treatments as helpful coping resources; (3) more frequently rate emotion-focused coping strategies as helpful; (4) less frequently report task-oriented coping strategies as helpful; (5) more frequently recommend an emotion-focused “best” strategy; and (6) predict a poorer prognosis for a person with depression. We also hypothesized that depression literacy would vary by vignette assignment. This study focused on how African American youth described their depression and understanding of the diagnoses (literacy). In addition, the Mental Health Literacy Framework [35], south to the do the following: 1) recognition (of disorders and types of distress); (2) knowledge (of mental illness, self-help, professional help, and where to find information); (3) attitudes/beliefs (that promote self-help and may influence treatment outcomes). The research team specifically sought to evaluate a gender-focused coping framework to the exploration of depression literacy in African American young adults.

Depression literacy is the ability to recognize the signs of depression in another individual; rate specific depression interventions as helpful or harmful; recommend appropriate ways to manage symptoms; and predict an individual’s prognosis with or without professional help [35,38]. Young females appear to be more depression literate and suggest more interpersonal treatments for depression than young males [36,39,40].

Method

A total of 53 African American young adults completed a survey about depression literacy. Ranging in age from 18 to 24 years, the sample was comprised of 38 females and 15 males enrolled at a Pacific Northwestern university. Respondents were separated by gender and randomly assigned to one of four groups. Each respondent was provided with a vignette and completed measures associated with depression, coping, emotion and prognosis.

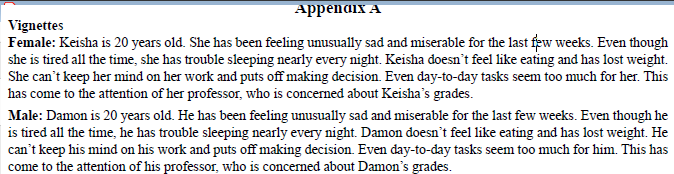

The mental health literacy survey consists of two vignettes from the original survey [41]. The vignette features either Tom or Mary, characters experiencing DSMIV (APA, 2007) depressive symptoms, who were renamed Damon and Keisha to reflect common African American names. After reading the vignette, students answered two open-ended questions: (a) What would you say, if anything, is wrong with Damon/Keisha? and (b) with or without professional help, what do you think are Damon/Keisha’s chance of recovery? Researchers coded participants as those who identified depression (ID group) and those who did not (No ID) based on the first question. Additionally, researchers coded responses to the second question into three categories: (a) will recover with professional help, (b) limited chance of recovery without professional help, and (c) will not recover without professional help. Respondents then categorized helping professionals (e.g., social workers, psychologists, and clergy) and interventions (e.g., antidepressants, vitamins, or admission into a psychiatric hospital) as helpful, harmful, or neither helpful nor harmful to the person in the vignette. Three additional questions, guided by work on mental illness in African American culture included: (a) Is there a stigma related to mental illness in the African American culture? (b) What is needed to reduce the stigma in the African American culture? and (c) Where can you find information on mental health?

Measures

Identified depression

Participants were randomly assigned to a culturally adapted vignette about depression and followed the procedure used by Jorm and colleagues [35,41] to identify what was wrong with the individual in the scenario (Appendix A). Those who responded to the open-ended item with “depressed” or “depression” were categorized as identifying depression.

Coping resources

Young adults answered questions about the harmfulness or helpfulness of self-help interventions for the person in the vignette [35]. Responses were coded -1 for harmful; 0 for neither harmful nor helpful; and 1 for helpful. Total number of suggested coping resources was a sum score across all 27 items.

Emotion- and task-focused coping strategies

Of the aforementioned 27 items, emotion-focused strategies were those that would buffer the scenario in the vignette (e.g., talking to a friend, physician, counselor, family, naturopath). Task-focused coping strategies were those aimed at directly eliminating depressive symptoms (e.g., medication, vitamins/minerals, deal with it alone, physical activity) [27,30]. We classified 13 of 27 items as emotionfocused strategies and 14 of 27 as problem-focused strategies. Responses were summed to compute total number of emotion- and task-focused coping strategies recommended to the person in the vignette.

Primary coping strategy

Participants responded to an open-ended item about how the person in the vignette would best be helped. Answers were entered verbatim, and content analysis was used to group suggested strategies into emotion- and task-focused responses [42].

Prognosis

Two items addressed the individual’s prognosis with or without professional help. After obtaining verbatim responses, responses were grouped into two themes: good prognosis (individual expected to recover) or bad prognosis (individual not expected to recover) [42].

Vignette assignment

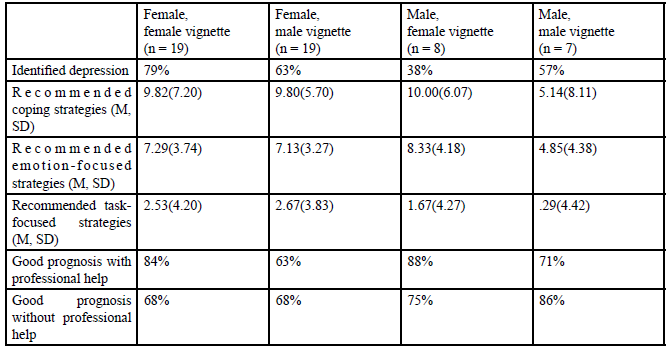

There were four groups of vignette assignments: Females with female vignette (n = 19); females with male vignette (n = 19); males with female vignette (n = 8); and males with male vignette (n = 7).

Results

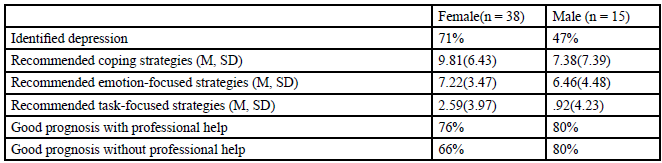

Table 1 includes depression literacy survey responses by gender. In addition, participants overwhelmingly suggested that emotionfocused coping strategies would best help the person in the vignette. A total of 46 of 53 (87%) of young adults said the individual would be best helped by “talking to someone,” like friends, family, and/ or counselor. An additional 4 participants (3 female) suggested a combination of emotion-focused and task-focused coping strategies (e.g., “talk to someone and get a hobby”), and 3 participants (1 female) reported task-only strategies (e.g., time management (e.g., time management, “doing what makes them happy”) for helping the individual. Table 2 presents depression literacy survey responses by vignette assignment.

Discussion

Echoing previous research results on gender differentiation in depression literacy, young adult females in our sample identified depression more frequently than young adult males [39,40,43,44]. Greater knowledge of depression…

In contrast, possessing such knowledge promotes mental health stigma reduction, increased help-seeking behaviors, early detection, and positive treatment outcomes for mental illness. The likelihood of help-seeking is greatest among young adults who possess the ability to recognize symptoms of mental illness and have the knowledge and encouragement to seek help.

Contrary to the hypotheses, females labeled a greater number of self-help interventions as helpful coping resources than males. Females suggested a greater number of emotion-focused and taskfocused help-seeking strategies to the person in the vignette rather than showing a preference for emotion-focused strategies. Nearly all young adults offered an emotion-focused coping strategy as the best way to help the person in the vignette. In fact, African American young adults uniformly rated emotion-focused coping as most helpful even when they could not identify depression in the vignette. As expected, females predicted a poorer prognosis for a person with depression than males.

The gender of the vignette influenced the identification of depression, total coping resources, coping strategies, and prognosis. Perhaps most interesting were responses of male participants: Males assigned to the female vignette had the lowest depression identification rate, but they offered the best prognosis and recommended the greatest number of helpful intervention resources and emotion-focused coping strategies. Males assigned the male vignette also anticipated a good chance of recovery but rated the individual in the vignette as having fewest resources as compared to the other three groups.

Limitations

The most noteworthy limitation of this pilot study is the small sample size [45]. Future studies should replicate our findings in a larger sample, conducting gender-by-response inferential analyses and using statistical techniques to compare quantitative answers with qualitative response themes. Subsequent research should also extend the present study to assess the relation between depression literacy and individual and community depression rates.

Summary

Our study suggests that African American young adult females are more literate about depression than African American young adult males, but both groups lack substantial awareness about the signs and symptoms of the depression, appropriate help-seeking interventions, and expected prognosis with and without treatment. Future research and practice priorities include improving depression literacy for young adults in the African American community, with particular emphasis on teaching males about how to recognize the signs of depression in other males and about the benefits of emotionand task-focused coping strategies.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests:

Authors report no conflict or competing interest.

References

Erickson, E. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis.View

Park, M., Mulye, T., Adams, S., Brindis, C., & Irwin, C. (2006). The health status of young adults in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39, 305-317. View

Konstam, V. (2015). Emerging and Young Adulthood - Multiple Perspectives, Diverse Narratives. Springer.View

Schlenberg, J., Sameroff, A., & Cicchetti, D. (2004). The transition to adulthood as a critical juncture in the course of psychopathology and mental health. Developmental Psychopathology, 16, 799-806.View

Guan, S.-S. A., & Fuligni, A. J. (2016, June). Changes in Parent, Sibling, and Peer Support During the Transition to Young Adulthood. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(2), 286- 299.View

Jones, R. M., Vaterlaus, J. M., Jackson, M. K., & Morrill, T. B. (2014, March). Friendship characteristics, psychosocial development, and adolescent identity formation. Personal Relationships, 21(1), 51-67.View

Dollinger, S., & Dollinger, S. (2003). Individuality in young and middle adulthood: An autophographic study. Journal of Adult Development, 10, 227-236.

Benson, J. E., Kirkpatrick Johnson, M., & Elder Jr, G. H. (2012, November). The Implications of Adult Identity for Educational and Work Attainment in Young Adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 48(6), 1752-1758 .View

Lin, K.-C., Twisk, J. W., & Rong, J.-R. (2011, April). Longitudinal Interrelationships Between Frequent Geographic Relocation and Personality Development: Results From the Amsterdam Growth and Health Longitudinal Study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(2), 285-292.View

Schubach, E., Zimmermann, J., Noack, P., & Neyer, F. J. (2016, March-April). Me, Myself, and Mobility: The Relevance of Region for Young Adults' Identity Development. European Journal of Personality, 30(2), 189-200.View

Choe, D. E., Stoddard, S. A., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2014, April). Developmental trajectories of African American adolescents' family conflict: Differences in mental health problems in young adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 50(4), 1226-1232.View

Heinze, J. E., Stoddard, S. A., Aiyer, S. M., Eisman, A. B., & Zimmerman, M. (2017, March). Exposure to Violence during Adolescence as a Predictor of Perceived Stress Trajectories in Emerging Adulthood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 49, 31-38.View

Turner, R., & Avison, W. (2003). Status variations in stress exposure: implications for the interpretation of research on race, socioeconomic status, and gender. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44, 488-505.View

Gutman, L., & Sameroff, A. (2004). Continuities in depression from adolescence to young adulthood: Contrasting ecological influences. Developmental Psychopathology, 16, 697-684.

Kessler, R., & Walters, E. (1998). Epidemiology of DSM-III-R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depression and Anxiety, 7, 3-14.View

Moreh, S., & O'Lawrence, H. (2016, Fall). COMMON RISK FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH ADOLESCENT AND YOUNG ADULT DEPRESSION. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, 39(2), 283-310.View

Culbertson, F. (1997). Depression and gender. American Psychologist, 52, 25-31.View

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Girgus, J. (1994). The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 424-443.View

Cyranowski, J., Frank, E., Young, E., & Shear, K. (2000). Adolescent onset of gender differences in lifetime rates of major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 21-27.View

Hankin, B., & Abramson, L. (1999). Development of gender differences in depression: description and possible explanations. Annals of Medicine, 31, 372-379.View

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2001). Gender differences in depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 173-176.View

Franko, D., Striegel-Moore, R., Bean, J., Barton, B., Biro, F., Kraemer, H., . . . Daniels, S. (2005). Self-reported symptoms of depression in late adolescence to early adulthood: A comparison of African-American and Caucasian females. Journal of Adolescent Health, 37, 526-529.View

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). (2009). African American women and depression. Arlington, VA: Author.

Whaley, A. (2001). Cultural mistrust and mental health services for African Americans: A review and meta-analysis. Counseling Psychology, 29, 513-531.View

Kim, S., Han, D., Trksak, G., & Lee, Y. (2014, January 21). Gender differences in adolescent coping behaviors and suicidal ideation: findings from a sample of 73,238 adolescents. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 27(4), 439-454.View

Matud, M. (2004). Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 1401-1415.View

Thoits, P. (1995). Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Extra Issue, 53-79.View

Adler, A. D., Conklin, L. R., & Strunk, D. R. (2013, December). Quality of Coping Skills Predicts Depressive Symptom Reactivity Over Repeated Stressors. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(12), 1228-1238.View

Horwitz, A., Czyz, E., Berona, J., & King, C. (2018, March). Prospective Associations of Coping Styles With Depression and Suicide Risk Among Psychiatric Emergency Patients. Behavior Therapy, 49(2), 225-236.View

Holroyd, K., & Lazarus, R. (1982). Stress, coping, and somatic adaptation In L. Goldberger & S. Breznitz (Eds). Handbook of stress: Theoretical and clinical aspects, 21-35.View

Dhillon, R., & Arora, M. (2017, July-December). Perceived Stress, Self Efficacy, Coping Strategies and Hardiness as Predictors of Depression. Journal of Psychosocial Research, 12(2), 325-333.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Larson , J., & Grayson, C. (1999). Explaining the gender difference in depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1061-1072.View

Rey Pena, L., & Extremera Pacheco, N. (2012). Physical- Verbal Aggression and Depression in Adolescents: The Role of Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies. Universitas Psychologica, 11(4), 1245-1254.View

Li, C., DiGiuseppe, R., & Froh, J. (2006). The roles of sex, gender, and coping in adolescent depression. Adolescence, 41, 409-415.View

Jorm, A., Korten, A., Jacomb, P., Christensen, H., Rodgers, B., & Pollitt, P. (1997). Mental health literacy: A survey of the public's ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Medical Journal of Australia, 166, 182-186.View

Byrne, S., Swords, L., & Nixon, E. (2015). Mental Health Literacy and Help-Giving Responses in Irish Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 30(4), 477-500.View

McCarthy, J., Bruno, M., & Fernandes, T. E. (2011). Evaluating Mental Health Literacy and Adolescent Depression: What Do Teenagers "Know?". The Professional Counselor, 1(2), 133- 142.

Ruble, A. E., Leon, P. J., Gilley-Hensley, L., Hess, S. G., & Swartz, K. L. (2013, September 25). Depression knowledge in high school students: Effectiveness of the adolescent depression awareness program. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(3), 1025-1030.View

Burns, J., & Rapee, R. (2006). Adolescent mental health literacy: Young people's knowledge of depression and health seeking. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 225-239.View

Cotton, S., Wright, A., Harris, M., Jorm, A., & McGorry, P. (2006). Influence of gender on mental health literacy in young Australians. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40, 790-796.View

Jorm, A. (2000). Mental health literacy: Public knowledge about beliefs about mental disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, 177, 396-401.View

Weber, R. (1990). Basic content analysis (2nd edition). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.View

Swami, V. (2012). Mental Health Literacy of Depression: Gender Differences and Attitudinal Antecedents in a Representative British Sample. PLoS ONE, 7(11).View

Martinez-Hernaez, A., Carceller-Macias, N., DiGiacomo, S., & Ariste, S. (2016). Social support and gender differences in coping with depression among emerging adults: a mixedmethods study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 10(2).View

Plackett, R. (1983). Karl Pearson and the Chi-Squared Test. International Statistical Review, 51, 59-72.View