Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour Volume 6 (2024), Article ID: JMHSB-185

https://doi.org/10.33790/jmhsb1100185Research Article

Faculty Knowledge and Awareness of College Student Mental Health Resources

Jessica E. Tye

Associate Professor, Department of Social Work, Winona State University,USA.

Corresponding Author Details: Jessica E. Tye, Associate Professor, Department of Social Work, Winona State University, 400 South Broadway Suite 300, Rochester, MN 55904. USA.

Received date: 11th January, 2024

Accepted date: 08th February, 2024

Published date: 10th February, 2023

Citation: Tye, J. E., (2024). Faculty Knowledge and Awareness of College Student Mental Health Resources. J Ment Health Soc Behav 6(1):185.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

College student mental health is one of the most relevant issues in higher education today. Faculty have contact with students daily; therefore, they are uniquely positioned to recognize and support students with mental health concerns. This quantitative study surveyed 149 faculty members to assess faculty knowledge and awareness of mental health resources. Results showed some faculty lacked knowledge to recognize students with mental health concerns and were unaware of campus guidelines and places to refer students. Implications of the findings indicate faculty need to be educated about students’ mental health, informed of resources and places to refer students, and advised of institutional guidelines. Mental health and higher education professionals can educate faculty to ensure they have the knowledge to recognize and refer students to seek help, increasing the likelihood of students’ academic success.

Keywords: College Students, Mental Health, Counseling, College Campuses, Faculty

Introduction

Mental health of college students has become one of the most relevant issues in higher education today. There has been a national increase in reporting of mental health issues. The rate of students seeking treatment and receiving diagnosis has increased substantially on college campuses [1,2]. From 2007 to 2017 on college campuses, the percentage of students with a mental health diagnosis rose from 22% to 36% and students seeking treatment increased from 19% to 34% [3]. This statistic does not consider the number of students who do not disclose to their institution that they have a mental health concern, do not seek services, or have not received a mental health diagnosis. While most students with mental health concerns will never cause harm to themselves or others while in college, the incidents that do occur on campus become headlines in local and national news [4].

The core of higher education is the educational relationship between faculty and students. Faculty are the frontline in communication and relationships with students as they have direct contact with them [5-8]. Faculty have contact with students daily; therefore, are most likely to discuss with students their mental health and experience potential concerning behaviors from a student [9]. These behaviors could be minor such as a student expressing distressing thoughts in a writing assignment or could be major such as a threatening act in the classroom. Most faculty have limited training with mental health issues and are armed only with written literature if they were to encounter an incident [10-12].

Campus counseling centers, the outreach from college and universities regarding mental health, most often staff professionals who have received formal training in addressing student mental health and supporting students’ concerns. College counseling centers provide services to help students, but research shows services remain underutilized by students and campus professionals [3,13]. In addition, often the silos on college campuses between the faculty and administrators create a communication breakdown that can hinder the support students may need [14].

This study surveyed 149 faculty members at a Midwestern, public four-year institution to assess faculty awareness of campus mental health resources and their knowledge to recognize students with mental health concerns. Additionally, the study looked at faculty desires for further information and preferred formats to receiving education on students’ mental health.

Literature Review

College students’ mental health has become critically important in recent years after violent acts at Columbine High School, Virginia Tech University, and Northern Illinois University [4]. A survey conducted by the Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors found the number of students seeking counseling is continuing to increase, as is the severity of the presenting problems [15,16]. The number of college students suffering from depression and suicidal thoughts is increasing [1,3,17]. The National College Health Assessment conducted by the American College Health Association [1] found that 29% of college students met the criteria for suicidal ideation and 79% of college students experienced moderate or high stress in the previous 30 days [1]. Additionally, 89% of college students who had academic challenges reported moderate or high levels of distress [1]. Counseling centers have had to learn creative ways to serve students as budgets and staffing have not grown in proportion to students’ needs [2,18].

College students with mental health concerns face many academic challenges and engagement stressors [19]. Eighty-six percent of college students with mental illness withdraw from college, compared to 45% for students without mental illness [20]. Giesler [21] found that emotional well-being is a predictor of college student persistence and degree completion. Results of a study by the National Alliance on Mental Illness [9] found 64% of students with mental health problems end up withdrawing from school. Students with mental illness have lower grade point averages, face social isolation, and experience discrimination more often than students without a mental illness [22,23]. Salzer [19] found that students with mental illnesses were less engaged on campus and have poorer relationships, which were related to lower graduation rates.

The college years are a time of significant transitions and stressors for students [24,25]. The Suicide Prevention Resource Center [26] stated:

Major life transitions, such as leaving home and going to college, may exacerbate existing psychological difficulties or trigger new ones. Moreover, leaving family and peer supports to enter an unfamiliar environment with higher academic standards can deepen depression or heighten anxiety. (p. 8)

Non-traditional students and graduate students also experience significant transitions and stressors [26]. Transitions and stress can become overwhelming if they exceed students’ coping abilities [27,28], which can cause negative coping mechanisms and trigger mental health problems [25,29].

The World Health Organization [30] defines mental health as, “A state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her own community” (para. 1). On the other hand, mental health problems or concerns refer to individuals with “less than optimal mental health” [31].

There has been an increase in the number of students seeking mental health services, an increase in the severity of mental health problems, and an increase in psychiatric medication usage [2,18,32]. The National Survey of Counseling Center Directors [18] reported 88% of directors have seen a significant increase in severe psychological disorders among their students and 87% of directors observed an increase in the number of students coming to campus already taking psychiatric medications. In addition, 92% of directors reported the number of students seeking help at their centers has been rapidly increasing in recent years. Eighty-eight percent of directors state the increased demand for counseling and more serious psychological problems have created staffing problems for their centers [18]. This evidence shows that mental health problems are increasingly prevalent on today’s college campuses.

Universities are faced with increased pressures to meet students’ mental health needs but remain underfunded and understaffed to meet the numerous needs of the campus community [13]. In response to tragic incidents on campuses and staggering research findings, colleges have begun to implement campus-wide mental health promotion and suicide prevention strategies [4]. One campus wide strategy to promote student mental health is to educate campus gatekeepers about recognizing signs of mental health concerns [33]. Gatekeepers are individuals who may come in contact with persons at risk for mental health concerns and have the opportunity to identify concerning behaviors. On college campuses, gatekeepers are those who regularly connect with students, including faculty, academic advisors, deans of students, student affairs staff, and residence hall staff [34]. Gatekeeper training is focused on educating individuals to recognize signs of distress and offer referrals to mental health professionals when needed. College faculty and advisors interact with students on a daily basis and are more likely to hear from a student with mental health concerns than a college counseling center staff member [9,35] therefore, they are uniquely positioned to recognize and support students with mental health concerns. Providing gatekeeper training to faculty members can help identify students with mental health concerns and assist them in receiving early mental health treatment [36].

Faculty and student interactions can positively affect students’ intellectual development, personal growth, learning outcomes, persistence, and degree completion [5-8]. Despite the benefits of student interactions, some faculty have negative attitudes, lack knowledge, and have discomfort towards students with mental illnesses [10-12]. A few studies have found the majority of faculty have positive expectations for students with mental illnesses [10,12] however, several studies have shown faculty knowledge, experiences, perceptions, attitudes, and comfort levels may possibly be related to faculty referring students to mental health professionals [10,11,37].

Becker et al. [10] examined “faculty and student attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, and experiences with students identified as having a mental illness” (p. 359). Becker et al.’s [10] results revealed although the majority of faculty have positive expectations for students with mental illnesses, some faculty are not knowledgeable and have negative expectations for students with mental illness. Faculty who had the potential for stigmatizing discrimination or social distancing had greater discomfort, were fearful, and less likely to help students with mental illness. Additionally, faculty who were not familiar with campus mental health services were less likely to discuss concerns with a student, convince students to seek help, and refer to counseling. Becker et al. [10] suggested educating faculty about mental illnesses and campus resources would increase the likelihood of referrals. Similarly, Quinn, Wilson, MacIntyre, and Tinklin [38] provided recommendations on ways higher education administrators can create a more inclusive and supportive environment for students with mental illness. Their suggestions included clearer policies, specific institutional procedures, gatekeeper training for staff/ faculty/administrators, educating students, peer support system, anti-stigma initiatives, and linking mental and physical well-being. Brockelman, Chadsey, and Loeb [11] conducted a similar study, and their results showed the majority of faculty felt they did not have sufficient knowledge of mental illnesses and desired more training and awareness of resources. Based on these studies, I desired to assess faculty awareness of campus mental health resources and desires for further education about college student mental health.

Through assessing faculty awareness and desires, mental health and higher education professionals can better prepare faculty to recognize and refer students to seek out mental health supports. Also, educators can use this information to develop curricula focused on faculty. This knowledge will assist professionals in supporting college students with mental health concerns in receiving needed services, increasing the likelihood of students’ academic success, and improving campus communities.

Methods

In this study I used a descriptive, quantitative research design to assess faculty awareness of campus mental health resources, knowledge to recognize students with mental health concerns, and desires for further education on students’ mental health. I also collected additional data regarding faculty prior referral experience and desired formats for further training. For the purposes of this study, mental health concerns refer to those with “less than optimal mental health” [31]. Mental health concerns do not meet the DSM-5 criteria for a diagnosis of a mental disorder; however, mental health problems put one at high risk for developing a mental disorder [39]. A questionnaire I developed containing self-report demographic questions was used in this study. Demographic questions included faculty members’ gender, age, and race. I also collected data on their awareness of campus resources and guidelines, knowledge to recognize concerning behaviors, prior referral experience, and desire for further mental health information.

The participants were full-time or part-time faculty members at a single, Midwestern public four-year university with a Carnegie classification of Masters M. There were 7,788 students enrolled, 93% of which are undergraduate students [40]. The population included all full-time or part-time faculty members at the Midwestern public four-year university, of which there were 316 full-time and 187 part time faculty members [40]. The sample consisted of 149 faculty members, which was a 28.8% response rate. There were 101 females (67.8%) and 48 males (32.2%) in the sample, of which 88.6% were White (n = 132) and 11.4% were non-White (n = 17).

Using convenience sampling techniques, I received an email list of all faculty members provided by the university’s communications department. I generated a recruitment email describing the study and included a website link to Qualtrics online survey software. The Qualtrics link contained the consent letter and the questionnaire regarding faculty awareness of and desires for further information. To ensure confidentiality, questionnaires did not ask identifying information and were identified using number codes. Informed consent was obtained by asking participants to agree to the consent letter prior to completing the online questionnaire. The consent stated participation was voluntary and respondents could withdraw at any time without penalty, identified the risks and benefits of participating, and provided contact information for the results or any questions. Participants were told by continuing to complete the survey they consented to participate in the study. This study was approved by the university Institutional Review Board (IRB# 1573-1965).

Results

Data collected was analyzed using descriptive statistics through SPSS statistical software. The survey data was downloaded from Qualtrics online software and imported into SPSS software for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to identify frequency of faculty who have referred students in the past, faculty awareness and knowledge, and preferred formats for further mental health information.

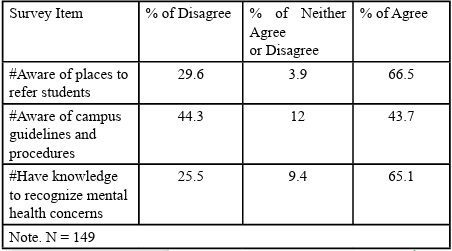

Of the faculty respondents, 117 (78.5%) had referred a student in the past to a mental health professional. Only 32 (21.5%) had never referred a student with mental health concerns. The percentage of faculty aware of places to refer students, awareness of campus guidelines and procedures to be followed, and knowledge to recognize and refer students are presented in Table 1. All three questions were scored on a 7-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The most preferred format of receiving further education about mental health concerns was workshops (64.4%) through conferences or faculty development trainings, followed by written literature (53.7%). Slightly less than half (43%) of respondents preferred online trainings/videos and 39.6% preferred talking to a specialist.

In summary, this study revealed most faculty respondents had referred a student in the past to a mental health professional (78.5%), felt they had sufficient knowledge of mental health concerns (65.1%), and were aware of several places to refer students (66.5%). Also, faculty members prefer mental health education through workshops (64.4%) and written literature (53.7%). Further analyses showed one fourth (25.5%) of respondents did not feel they were knowledgeable about mental health, over one-fourth (29.6%) indicated they were unaware of places to refer students, and almost half (44.3%) of faculty were unaware of campus guidelines and procedures to be followed when referring students.

Discussion and Recommendations

The rise in mental health issues can provide an opportunity for college administration and faculty to work together for the betterment of students. This study found that some faculty lacked knowledge to recognize students with mental health concerns, but that most faculty were interested in receiving further education about students’ mental health. Mental health and higher education professionals can take this opportunity to aid faculty in this education. My findings also showed that while most faculty were willing to refer a student to go get help, they may not have known where to send them and what their role could be in reporting the student’s issues to the institution.

The results of this study strengthen the implications of my findings and indicate faculty need to be educated about student mental health, informed of resources and places to refer students, and advised of institutional guidelines. These are consistent with Quinn, Wilson, MacIntyre, and Tinklin [38]’s recommendations of ways higher education administrators can create a more inclusive and supportive environment for students with mental health concerns. While traditional faculty workshops, campus emails about promotion, and written literature could be one way to provide this information to faculty, I also recommend a more direct approach to informing faculty of the resources offered on the campus [38]. First, outreach needs to be made to the academic deans to discuss resources and guidelines of the institution. Second, college counselors should directly schedule with individual academic departments to set up trainings. While more time consuming, this takes away the optional aspect many faculty workshops have on campus that often attract the same people. By meeting with the entire department, most faculty would directly receive this information. Third, connections should be made with new faculty orientation programs, so that new faculty as they come into the university are exposed to student mental health information.

This direct approach to the faculty is designed to build the personal relationship between faculty and college counselors. This relationship along with the education will make it easier for faculty members to refer students in need of further services. Faculty will be aware of campus resources and institutional procedures, have the knowledge to recognize students of concern, and know a personal contact instead of a campus office to refer students too. The personal touch and humanization of the process will increase the likelihood of faculty referring students of concern and create a more inclusive environment for students with mental health challenges [10,38].

Faculty reach students daily; therefore, they are uniquely positioned to recognize and support students with mental health concerns. Higher education and mental health professionals can educate faculty to ensure they have the knowledge to recognize and refer students to seek help. This will assist college students with mental health concerns in receiving needed services, increasing the likelihood of academic success, and improving campus communities.

Competing Interests:

The author reports no conflict or competing interests.

References

American College Health Association (2022). American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment III: Undergraduate Student Reference Group Executive Summary Spring 2022. Silver Spring, MD: American College Health Association.View

Brown, S. (2020). Overwhelmed: The real campus mental health crisis and new models for well-being. Washington, DC: The Chronicle of Higher Education. View

Lipson, S. K., Lattie, E.G., Eisenberg, D. (2018). Increased rates of mental health services utilization by U.S college students: 10 year population-level trends (2007-2018). Psychiatric Services, 70(1), 60-63.View

Kraft, D. P. (2011). One hundred years of college mental health. Journal of American College Health, 59(6), 477-481. View

Astin, A. W. (1993). What matters in college: Four critical years revisited (Vol. 1). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.View

Kuh, G. D., & Hu, S. (2001). The effects of student-faculty interaction in the 1990s. The Review of Higher Education, 24(3), 309-332. View

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How college affects students: A third decade of research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. View

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. View

National Alliance on Mental Illness (2012, November 1). College survey of college student with mental health problems. Business Wire. View

Becker, M., Martin, L., Wajeeh, E., Ward, J., & Shern, D. (2002). Students with mental illness in a university setting: The relationship between college students’ beliefs about the definition of mental illness and tolerance. Journal of College Counseling, 3, 100-112.View

Brockelman, K. F., Chadsey, J. G., & Loeb, J. W. (2006). Faculty perceptions of university students with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 30(1), 23-30.View

Sniatecki, J. L., Perry, H. B., & Snell, L. H. (2015). Faculty attitudes and knowledge regarding college students with disabilities. AHEADAssociation, 28(3), 259.View

LaFollette, A. M. (2009). The evolution of university counseling: From educational guidance to multicultural competence, severe mental illness and crisis planning. Graduate Journal of Counseling Psychology, 1(2), 1-8.View

O'Connor, J. S. (2012). Factors that support or inhibit academic affairs and student affairs from working collaboratively to better support holistic students' experiences: A phenomenological study. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA.View

Reetz, D. R., Bershad, C., LeViness, P., & Whitlock, M. (2016). The Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors annual survey [Report]. Retrieved from http://www. aucccd.org View

Sieben, L. (2011, April 3). Counseling directors see more students with severe psychological problems. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.chronicle.com View

Hunt, J., & Eisenberg, D. (2010). Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(1), 3-10.View

Gallagher, R. P. (2014). National Survey of Counseling Center Directors. Alexandria, VA: International Association of Counseling Services.View

Salzer, M. S. (2012). A comparative study of campus experiences of college students with mental illness versus a general college sample. Journal of American College Health, 60(1), 1-7.View

Collins, M. E., & Mowbray, C. T. (2005). Higher education and psychiatric disabilities: National survey of campus disability services. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75(2), 304-315.View

Giesler, F. (2022) College success requires attention to the whole student. Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour, 4(1), 154.View

Blacklock, B., Benson, B., Johnson, D., & Bloomberg, L. (2003). Needs assessment project: Exploring barriers and opportunities for college students with psychiatric disabilities. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Disability Services.

Eisenberg, D., Golberstein, E., & Hunt, J. (2009). Mental health and academic success in college. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 9, 40-41. View

Iarovici, D. (2014). Mental health issues and the university student. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.View

Reynolds, E. K., MacPherson, L., Tull, M. T., Baruch, D. E., & Lejuez, C. W. (2011). Integration of the brief behavioral activation treatment for depression (BATD) into a college orientation program: depression and alcohol outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 555.View

Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (2004). Promoting mental health and preventing suicide in college and university settings. Retrieved from http://www.sprc.org/View

Freeburn, M., & Sinclair, M. (2009). Mental health nursing students' experience of stress: burdened by a heavy load. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16(4), 335-342.View

Kucirka, B. G., (2013). Navigating the faculty-student relationship: A grounded theory of interacting with nursing students with mental health issues. (Doctoral dissertation, Widener University). Retrieved from http://gradworks.umi. com/35/70/3570583.htmlView

Cook, L. J. (2007). Striving to help college students with mental health issues. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing, 45(4), 40-44.View

World Health Organization. (2019). Mental health: A state of well-being.View

MacKean, G. (2011, June). Mental health and well-being in post-secondary education settings. In CACUSS preconference workshop on mental health. Retrieved from http:// campusmentalhealth.caView

Kraft, D. P. (2009). Mens Sana: The growth of mental health in the American college health association. Journal of American College Health, 58(3), 267-275.View

Wallack, C., Servaty-Seib, H. L., & Taub, D. J. (2013). Gatekeeper training in campus suicide prevention. In D. J. Taub & J. O. Robertson (Eds.), Successful approaches to campus suicide prevention (New Directions for Student Services) (pp. 27-41). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.View

Servaty-Seib, H. L., Taub, D. J., Lee, J., Morris, C. W., Werden, D., Prieto-Welch, S., & Miles, N. (2013). Using the theory of planned behavior to predict resident assistants’ intention to refer students to counseling. The Journal of College and University Student Housing, 39(2), 48-69.View

Nelson, K. L. (2019). Mental health and advising on college campus. Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour, 1, 101.View

Yufit, R. I., & Lester, L. (2004). Assessment, treatment, and prevention of suicidal behavior. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.View

Backels, K., & Wheeler, I. (2001). Faculty perceptions of mental health issues among college students. Journal of College Student Development, 42(2), 173-176.View

Quinn, N., Wilson, A., MacIntyre, G., & Tinklin, T. (2009). ‘People look at you differently’: Students’ experience of mental health support within higher education. British Journal of Guidance & Counseling, 37(4), 405-418.View

Santor, D., Short, K., & Ferguson, B. (2009). Taking mental health to school: A policy-oriented paper on school-based mental health for Ontario. Paper prepared for The Provincial Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health at CHEO. Retrieved from http://www.excellenceforchildandyouth.caView

U.S. Department of Education. (2018). Fast facts. National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from http://nces. ed.gov/fastfacts/View