Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour Volume 6 (2024), Article ID: JMHSB-186

https://doi.org/10.33790/jmhsb1100186Research Article

Classroom Proximity, Students’ Perceptions of Their Teacher: A Proximity Disrupt-Control Exploration in High School

Su Jin1, Rouzhou Zhang2, Xiaoxi Li3*, and Aimin Wang4

1Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program, Department of Educational Leadership, Miami University, 201 McGuffey Hall, Oxford, OH 45056, USA.

2,4Department of Educational Psychology, Miami University, 201 McGuffey Hall, Oxford, OH 45056, USA.

3*Department of Deyu School of Marxism, Dalian University of Foreign Languages, Dalian University of Foreign Languages, No.6, West Section, Lvshun South Road, Lvshunkou District, Dalian 116044, Liaoning,China.

Corresponding Author Details: Xiaoxi Li, Department of Deyu School of Marxism, Dalian University of Foreign Languages, Dalian University of Foreign Languages, No.6, West Section, Lvshun South Road, Lvshunkou District, Dalian 116044, Liaoning, China.

Received date: 30th April, 2024

Accepted date: 26th June, 2024

Published date: 28th June, 2024

Citation: Jin, S., Zhang, R., Li, X., & Wang, A., (2024). Classrom Proximity, Students' Perceptions of Their Teacher: A Proximity Disrupt-Control Exploration in High School. J Ment Health Soc Behav 6(1):186.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Prompted by the need to understand factors that enhance student learning and achievement, this study investigates the causal relationship between student-teacher proximity (STP) and student evaluations of teachers (SET). It incorporates students' STP preferences and in-class disruptive behavior (DB). An initial study with 68 American high school students revealed a positive correlation between STP and SET, with no significant link to DB. A follow-up study with 192 Chinese students assessed an intervention based on STP preferences and DB levels. Findings indicated that SET-individual tendency, student preferred teacher (SP Teacher), and student-preferred teaching content (SP Teaching Content) significantly influenced both SET behavior and character. This research suggests that optimizing STP can improve student engagement and reduce disruptive behaviors, thereby fostering a more effective educational environment.

Keywords: Student-Teacher Proximity (STP), Student Evaluations of Teachers (SET), In-Class Disruptive Behavior (DB), STP Preferences

Introduction

In-class disruptive behavior and its impact on academic achievement have been extensively studied, showing a negative correlation due to the distractions caused during lessons [1-3]. Recent studies suggest that students’ evaluations of teachers may reflect the level of attention and support received from them. Teachers often develop negative attitudes toward frequently disruptive students, leading to reduced support and subsequently lower student evaluations of these teachers.

The classroom environment significantly influences disruptive behavior. While much of the literature focuses on physical aspects like temperature and lighting, few studies address seating arrangements and student-teacher proximity. Research indicates that close proximity to the teacher reduces misbehavior as teachers pay more attention to nearby students, enhancing their behavior and attention control [4]. Conversely, students seated farther away tend to receive less attention, potentially increasing distractions.

The relationship between student-teacher proximity and students’ evaluations of teachers is critical. Teachers perceive students seated closer as more attentive, leading to more patient and friendly interactions, which in turn results in more positive evaluations [5]. Proximity also affects students’ perceptions of educational interactions, enhancing their understanding of lectures through better access to nonverbal cues and clearer verbal expressions.

Understanding these proximity effects is essential for improving classroom seating design and management, enhancing both learning and teaching effectiveness. This study aims to analyze the relationships between student-teacher proximity, student evaluations of teachers, and in-class disruptive behavior to provide insights for high school classroom management and future research.

Literature Review

Student-Teacher Proximity

Student-teacher proximity is the actual distance from a student to the teacher, either measured in centimeters, or defined by the rows which students are seated [6]. Hall [7] first indicates the value of studying student-teacher proximity and categories the distance between a student to the teacher into accepted and rejected zones. Exhaustive findings have shown that physical layout of the seating can support learning objectives and a student’s achievement [8,9]. A student who sits close to the teacher is more attentive to the lectures being taught [10]. It is clear that more comprehensive knowledge on student-teacher proximity can assist classroom seating arrangement, which has inevitable influence on the extent and nature of student interaction and perception. Therefore, close student-teacher proximity could help create an environment of effective learning and efficient teaching.

Measurement techniques in proximity research have been a major concern in most of the literature. The major measurement techniques are divided into three categories: projective or simulation studies, quasi-projective or laboratory studies, and interactional or naturalistic studies. According to the previous study of proximity zone, the classroom was divided into two zones (close to teacher: 3-5m/ remote to teacher: 5-10m), which are in accord with Hall’s [7] category of proximity zone and Mehrabian’s [11] classification of proximity zone.

Student’s In-class Disruptive Behavior

A student’s in-class disruptive behavior is the behavior considered as inappropriate for the setting or situation in which it occurs. Clarles [12] notes 13 types of students’ disruptive behavior as: inattention, apathy, needless talk, moving about the room, annoying others, disruption, lying, stealing, cheating, sexual harassment, aggression and fighting, malicious mischief, and defiance of authority. Houghton and his colleagues [13] conduct a study among high schools in Britain, and stresses the most troublesome behavior in class is not the serious one as violence, physical assault on teachers, bullying, but identified by teachers as a minor break of the rules. The misbehavior occurs on a daily basis in high frequency, makes teachers stressed, and disrupts the class. The most frequent and disruptive problems identified by teachers are minor in nature, which means they will not cause serious results a single time, but will disrupt the class by its frequent appearances [14], such as talking out of turn, hindering others, and idleness/slowness.

Studies show that in most classes there always be 10-20% of students existing as troublesome students and disrupting teaching [13]. It has been found that a student’s disruptive behavior often has a negative relationship with the student’s academic achievement. The major reason for this negative relationship is reported to be the student’s disruptive behavior distracting them from the lessons being taught in the classroom [2]. Besides, a teacher has less interaction with the student who has more disruptive behavior, and the teacher shows less patience when answering questions and gives fewer opportunities to his/her individual developments [15]. Therefore, student-teacher intervention in the classroom is necessary in order to reduce and eliminate a student’s in-class disruptive behavior and the associated effects it has on teachers and other students [14].

Proximity Strategy to Control Disruptive Behavior

Proximity strategy is an essential theme in teaching since the physical layout of the seating can affect disruptive behavior and learning. Black [16] finds a poor seating location can affect a student’s learning by 50% when he/she stands or sits 20 feet (6 meters) or more away from the teacher within the classroom. Anguiano [17] learned that students sitting in the front row and in the center desks of each row had the greatest participation. Haghighi and Jusan [8] indicate that modifying seating arrangements to provide closer proximity can be a method to reduce DB and positively influence teaching and learning in the classroom. Also, Ervin and his colleagues [18] have sufficiently examined the effectiveness of STP intervention strategy in the field of special education.

Modern classrooms had been curved to arrange a maximum of three rows of seats so that all students were within closer proximity to the teacher. However, there are psychological thoughts emphasizing external control limits children’s ability to be self-regulating and keeps children in an ego-centrism state. When students are regulated by means of external control, it is very difficult for them to assimilate guidelines for appropriate behavior. Because they have not grasped self-regulatory behavioral techniques for self-control [9]. Additionally, many students at this age are concerned with being accepted by their classmates as “cool”, and trying to avoid public praise through DB.

Moreover, though physical DB are explicitly studied, emotional DB are seldom addressed in most educational observations. It is hard for researchers to record this psychological behavior because an observed physical behavior possibly combines multiple inner activities. we’ve got no reason to suppose an equal level of disruption in the same behavior, meanwhile, we could not expect the same inner activity would necessarily occur in the same disruption situation. Educators are too often failing to realize students’ emotional DB, which should be recognized in their own contests, rather than measured by standardized rules that are not likely to work for the whole class. To be specific, DB is what a student knows he/she should not do it. “An accidental hiccup during quiet work time is not misbehavior, but when feigned for the purpose of disrupting a lesson, the same behavior is justifiably disapproved [19]”.

Student’s Evaluation of the Teacher (SET)

Using a student’s rating to evaluate the teacher (SET) dates back to 1926, when the Purdue Rating Scale of Instruction was first introduced [20]. Specially, numerous methodologically unsound studies on SET were published in the 1970s [21], which is labeled as “the golden age of research on student evaluations” by Centra [22]. Since then abundant investigations have confirmed that SET is a reliable and valid method of measuring an instructor's effectiveness [23-25]. Compared with other formal ways to measure teachers’ teaching, such as evaluations carried out by peers, administrators, and the individual instructors themselves (as self-evaluation), SET is used to indicate teaching productivity and identify teaching attributes to improve learning [25-27]. Thus, SET becomes “a standard component of the way colleges and universities access the quality of an instructor’s teaching for purposes of promotion and tenure, develop necessary classroom skills [28], as well as merit raise allocations [29]”.

Even with all the findings showing that SET is one of the best terms that is supported by empirical research to efficiently measure teachers’ teaching, the results on SET were really “ambiguous” and “contradictory” [30]. VanArsdale and Hammons [20] state that “student evaluations are just congruent with faculty peer evaluations; a professor's age, gender, years of experience, and personality have minimal effects on student evaluations; and that the student variables of personality, year in school, gender, age and academic performance have negligible impact on student ratings (p.34-35).” Some researchers also find that instructors can simply “buy” better evaluation scores by inflating students’ grade expectations [31-34]. Nevertheless, Soper [35] presents results showing that “students’ perceptions of their teachers’ abilities have no connection with what they learn (p.95).” Inconsistent with previous findings, Rodin and Rodin [36] even find a strong negative correlation between mean SET scores and performance on tests in calculus classes, indicating that less effective teachers could get higher evaluations. Consequently, though thousands of studies have been investigating SET, the results are still far from sufficient. More detailed elements that may affect SET should be included in future SET studies.

Proximity, Student’s In-class Disruptive Behavior and Student’s Evaluation of The Teacher

As soon as SET was introduced at several major universities in the U.S. in the 1920s [20], research on SET and the various factors that may affect SET had showed “mixed results” [37]. Plenty of studies report the influence of class enrollment on SET [25,38,39]. Findings show that the number of rows per classroom is negatively associated with student ratings. That is, the greater the number of rows in the classroom, the lower the average student evaluations [34]. Nonetheless, there are still a few researchers who find no significant relationship [40] between class enrollment and SET, while others have found a curvilinear relationship between the two aspects [9]. In summary, student-teacher proximity is of significant importance in students’ learning experience and schools’ classroom seating management.

Beside class’s characteristics, the instructor’s characteristics are also important determinants of SET [34,41]. Researchers show male instructors get better scores than females, and younger instructors are more popular than older ones [31]. In addition, individual student differences (directed toward particular categories of students such as accepted/rejected, high ability/low ability, Black/white, or male/ female) appear to influence how teachers are perceived [42-44]. For previous literature, SET focuses on both teachers’ personal traits (character) and the quality of their verbal and nonverbal interaction (behavior) should be paid sufficient attention [45]. Additionally, in the classroom, physical proximity can be used to communicate caring and concern. The greater the distance between a student and the teacher, the more likely the student will engage in disruptive behaviors. Meanwhile, the misbehaving student may get less support from the teacher, and perceives more negativity in the teacher’s behavior and character.

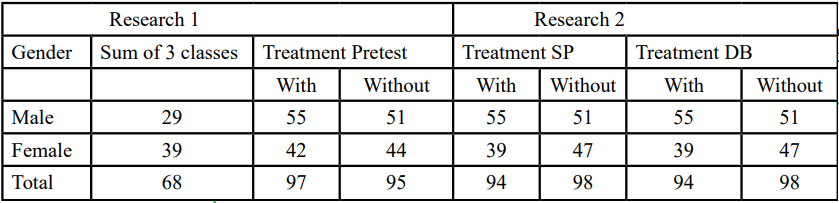

The current study contains two parts. The pilot study measured classroom student-teacher proximity (STP), observed each student’s in-class disruptive behavior (DB) and collected each student’s ratings on the teacher’s behavior and character (SET). It included 68 students (29 males) from three classes in a high school of the United States, according to which STP positively predicted SET. However, non-significant correlation on DB was found in either STP or SET.In order to further test and examine the generality of the findings, 192 students (106 males) from a high school in China and manipulated STP according to student’s preference of STP (STP-preferred: close vs. remote to teacher) and DB (low vs. high).

Research Question for Study 1

Exploring the significant correlation between classroom student teacher proximity, a student’s in-class disruptive behavior, and SET, including a student’s evaluation of both the teacher’s behavior and the teacher’s character.

Research Question for Study 2

1. Was there a significant causal relationship between STP and SET, controlling the impact of pretest and student’s preference of STP?

2. Was there a significant causal relationship between STP and SET, controlling for the frequency level of students’ disruptive behavior (DB level)

Methodology

Participants

The samples in Research 1 were gathered from a public, coeducational high school in the Midwest region of the United States. The participants were tenth-grade students, with ages ranging between 14 and 16, who were enrolled in an American history class taught by a single teacher. The sample consisted of 75 students, with 39 females and 29 males who provided both parental consent and student assent letters to participate in the study. Of the 75 students, 68 voluntarily participated in the observation and evaluation processes and were included as valid data sources.

Research 2 recruited 192 Chinese students (106 males and 86 females) from a senior high school in Beijing, China. All participants were first-year senior high school students, ages ranging from 15 to 16, who were taking Chinese Literature courses instructed by two female teachers. The study utilized a quasi-experimental design, with four classes randomly assigned to three different treatments based on the Solomon Four Group design. The specifics of these treatments are described in the procedure section of the study.

Both studies collected data prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, with IRB approvals obtained beforehand.

Instrument

Teacher Behavior and Character Evaluation Survey

Three separate surveys, regarding students’ evaluation of teacher’s behavior (SET Behavior), students’ evaluation of teacher’s character (SET Character) and student’s preference of teacher(SP Teacher) and teaching content (SP Teaching Content), are included in the Teacher Behavior and Character Evaluation Survey, which was developed by Brooks [46]. There are 11 questions related to SET Behavior. For each question, students grade their teacher based on their teacher’s performance in the class with a grading interval from 0 to 100. There are 13 “5-point Likert Scale” questions related to SET Character. The internal consistency reliability (Cronbach alpha) of the Chinese-translated survey was .94 and .88 (N=192), respectively. The content validity of this survey was assessed by experts from both the translation field and the field of education. The last part asked about “how do you like the teacher/ teaching content”, and “When you evaluate your teachers, you are a person who always tends to give them (1-5)”, to measure the SP Teacher, SP Teaching Content and SET-individual tendency.

Proximity Related Instruments

The research included a Seat Preference Survey, and a Proximity (Seat) Recording Chart. The Seat Preference Survey was conducted to gather data on students’ preference of seat according to their own choice of student-teacher proximity (Close/ Remote to teacher) in response to Treatment SP. The Proximity (Seat) Recording Chart was used to track SET and DB by recording students’ seating position in the classroom. The STP was calculated according to “the Pythagorean Theorem” in meter (m). The classroom was divided into two zones (close to teacher: 3-5m/ remote to teacher: 5-10m) based on Hall’s [7] category of proximity zone (social distance-far phase/ public distance-close phase) and Mehrabian’s [11] classification of proximity zone (attraction/ avoidance).

Student’s In-class Disruptive Behavior Recording Form

The Student’s In-class Disruptive Behavior Recording Form is an instrument that was used in a study to record and categorize students’ in-class disruptive behavior. The instrument was developed based on Charles’ [12] systematic categories of disruptive behavior, which includes 13 sub-types of misbehavior. The instrument was modified to fit the specific characteristics of Chinese high school students and classroom settings based on the teacher’s recommendation. The observation was conducted on an individual student, and a video recorder was used to capture the behavior, which was then recorded on the Students’ In-class Disruptive Behavior Recording Form . The duration of the behavior was coded by two trained research assistants based on the videotaped material, and the observations were checked every five seconds during the entire observation period. Moreover, the frequencies of students’ disruptive behavior were regrouped into levels (DB Level: low/ high) to magnify the potential difference among students. The recording form was assessed by credentialed experts and confirmed by a pilot study.

Procedure

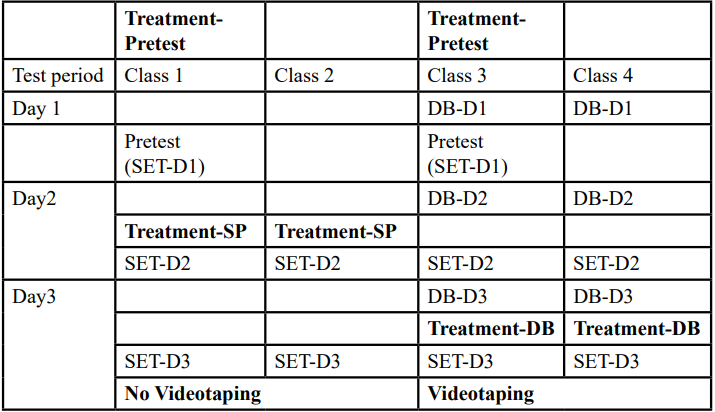

In the first research, the observers independently observed each participant’s behavior using the Student’s In-class Disruptive Behavior Recording Form. Participants were asked to finish the Teacher Behavior and Character Evaluation Survey after the observations, with their seats recorded. The second research utilized a modified Solomon 4 group design to control for potential contributing variables. The Solomon 4 group design was employed to counterbalance the effect of pretest (SET-Day1) on the subsequent SET survey and to determine the effect of treatment on students' evaluations of their teachers regardless of their increasing familiarity with the teacher and the SET survey's impact on the final results. To achieve the experimental design, three different treatments were randomly assigned to four classes during the three-day experimental period: Treatment SP, Treatment DB, and Treatment Pretest.

Treatment SP involved manipulating seating arrangements according to students' preferences for student-teacher proximity (STP) to test the effect of the experimental proximity zone on SET while controlling for students' STP preferences. Treatment DB involved rearranging seating based on students' disruptive behavior (DB) levels to test for the effect of the experimental proximity zone while controlling for the frequency of students' disruptive behavior. Treatment Pretest examined the effect of pretest on the subsequent SET survey.

The general procedure involved random seat assignments, distribution of treatments, completion of the Teacher Behavior and Character Evaluation Survey, and random pretest assignments. Videotaping of students' in-class disruptive behavior was carried out in the two classes with Treatment DB. The procedure of Treatment SP involved recording original seat arrangements and surveying students’ preference STP on Day 1, conducting Treatment SP on Day 2, and returning students to their original seats on Day 3. Treatment DB involved recording seating arrangements and videotaping students' disruptive behavior on Day 1, videotaping students' disruptive behavior, combining DB codes (Sum the results from Day 1 and Day 2) on Day 2, and conducting Treatment DB on Day 3. Detailed arrangement procedures in appendix IV.

Results

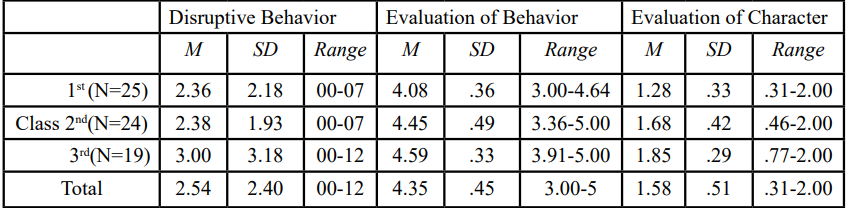

The first study analyzed measured classroom student-teacher proximity, observed each student’s in-class disruptive behavior and collected each student’s ratings on the teacher’s behavior and character as variables (Table 2). Non-parametric analysis (variables were not normally distributed) indicated that no significant difference on a student’s evaluation of the teacher’s character (U = 674.00, p > .05), a student’s evaluation of the teacher’s behavior (U = 771.50, p > .05), or observed a student’s in-class disruptive behavior (U = 470.50, p = .23) between the gender groups. Thus, it was reasonable to combine the two gender group. In-depth exploratory results showed that student-teacher proximity was significantly correlated with a student’s evaluation of the teacher’s behavior (rs = .25, p < .05, r2= .07), and a student’s evaluation of the teacher’s character (rs= .36, p < .05, r2= .13). The correlation between a student’s evaluation of the teacher’s character and his/her classroom proximity was significantly stronger than the correlation between the student’s evaluation of the teacher’s behavior and his/her classroom proximity (Z = .69, p < .05). No significant correlation (rs = .18, p > .05) existed between student-teacher proximity and a student’s in-class disruptive behavior. Besides, neither a student’s evaluation of the teacher’s behavior (rs= .02, p > .05), nor his/her evaluation of the teacher’s character (rs= .08, p > .05) was found significantly correlated with the student’s in-class disruptive behavior.

Corresponding to the first/pilot study, the second/main research was conducted to explore the causal relationship between STP and SET under a more scientific and systematic research design in a convenient Chinese content with three different treatments, Treatment SP, Treatment Pretest and Treatment DB. Preliminaries correlation and multi-variances analysis were conducted, and found a significant positive correlation between SET Behavior and SET Character during each of the three-day data collection, r1(93) = .22, p = .03; r2(188) = .52, p < .001; r3 (192) = .53, p < .001 respectively. In order to explore the relationship among SET, STP, and the two types of STP-arranged (STP-arranged (SP) based on student’s preference of STP and STP-arranged (DB) based on student’s DB Level), controlling SET-individual tendency, SP Teaching Content and SP Teacher, a Partial Correlation was conducted as the preliminary analysis for the treatments in this study. The result of this partial correlation is summarized in Table 3.

Table 2: Description of A Student’s In-class Disruptive Behavior and His/her Evaluation of the Teacher by Class and Gender

Table 3: Partial Correlation for SET, STP and STP-arranged, by controlling SET-individual tendency, SP Teaching Content and SP Teacher

Above table shows statistically significant correlations among STP, STP-arranged, SET Behavior and SET Character on Day 2, producing the significant r values r1(39) = .27, p < .05 (one-tailed); r2(39) = .30, p < .05 (one-tailed) respectively. There are significant correlations between STP-arranged (SP) and SET Behavior, r3(39) = .47, p < .05 (two-tailed); and SET Character, r4 (39) = .31, p < .05 (two-tailed). On Day 3, significant correlation was found between SET Character and STP, r5(39) = .53, p < .05 (two-tailed); and STP arranged (DB), producing the significant r values r6 (39) = .46, p < .05 (two-tailed). However, SET Behavior was not significantly correlated to either STP or STP-arranged (DB) on Day3.

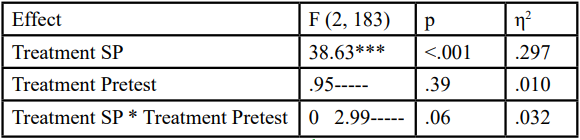

Further statistical analyses were conducted to test the effect of STP arranged (SP) on SET, controlling the impact of Treatment Pretest and students’ preference of STP (Table 4).

The multivariate analysis indicated a significant main effect of the manipulation of STP based on students’ individual preference of STP (Treatment SP), F (2, 183) = 38.63, p < .001, η2 = .297. A univariate test indicated the experimental group (M = 55.52, SD = 4.87) was significantly higher than the control group (M = 44.71, SD = 10.79) on SET Behavior, F (1, 184) = 77.57, p < .001, η2= .297. Meanwhile, the experimental group (M = 53.00, SD = 9.28) was significantly higher than the control group (M = 47.12, SD = 9.86) on SET Character, F (1, 184) = 17.33, p < .001, η2= .086. However, neither significant effect of Treatment Pretest nor the interaction between Treatment Pretest and Treatment SP was found.

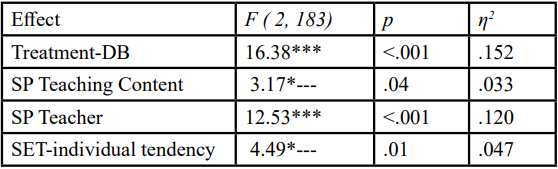

In order to test whether the manipulation of STP according to students’ DB Level (Treatment DB) had an effect on SET behavior and SET character on Day 3, controlling SET-individual tendency, SP Teaching Content and SP Teacher, a Multivariate Analysis of Covariance was conducted (Table 5), and suggested a significant main effect of the manipulation of STP according to students’ DB Level (Treatment DB), F (2, 183) = 16.38, p < .001, η2= .152. A univariate test indicated students with Treatment DB (M = 53.27, SD = 4.99) gave significantly higher evaluations than students without Treatment DB (M = 46.64, SD = 12.49) on SET Behavior, F (1, 184) = 22.51, p < .001, η2= .109. Meanwhile, students with Treatment DB (M = 52.75, SD = 8.57) gave significantly higher evaluations than students without Treatment DB (M = 47.34, SD = 10.60) on SET Character, F (1, 184) = 19.48, p < .001, η2= .096.

Table 5: Multivariate Analysis of SET by Treatment DB, by controlling SP Teaching Content, SP Teacher and SET-individual tendency

Three covariates, SP Teaching Content, SP Teacher and SET individual tendency, are significantly related to SET Behavior and SET Character, F (2, 183) = 3.17, p = .04, η2= .033, F (2, 183) = 12.53, p < .001, η2= .120, F (2, 183) = 4.49, p < .001, respectively. The results suggest these three covariances are eligible to be included in this model. Among these three covariances, SP Teacher had a higher effect size (η2= .120) than the other two.

Discussion and Conclusion

The research findings support the relationship between STP and students’ rating of their teacher’s behavior and character [9,34]. In many studies, questionnaires and surveys of SET are applied as the most important measure of teaching effectiveness [47]. According to Patrick and Smart [48], teaching effectiveness includes three factors: respect for students, organization and presentation skills, and ability to challenge students. The first factor, respect for students, refers to the teacher’s character and the other two factors refer to the teacher’s behavior. This classification was confirmed by the SET survey used in this research. Two additional questions related to student’s preference of teacher (SP Teacher) and teaching content (SP Teaching Content) were added to the end of the Teacher Behavior and Characteristic Evaluation Survey [46]. Significant covariates were found for both factors. In addition, the result showed that a student’s preference of a teacher had a higher impact on SET. This finding was supported by Hamermesh and West’s study [49] which indicated students gave higher evaluation to their preferred teachers. Hall’s [7] study indicated that much of nonverbal communication is done by hand gestures and body positioning which is influenced by spatial STP. A study of a student’s perception of teacher’s verbal and nonverbal behavior showed the influence on SET Character [50], and the significant effect of the manipulation of STP (based on students’ preference of STP) on SET Character was strongly confirmed by the main study. Meanwhile, no significant relationship between student’s in-class disruptive behavior (DB) and SET was found. The insignificant result was probably due to the potential observation bias of students’ disruptive behavior.

The status of student’s expectation of STP (meet/ violated), SP Teacher and SP Teaching Content were taken into consideration in the second research to analyze the causal relationship related to SET. After revising the experimental procedure by considering the impact of the above factors, the second/main study revealed the significant relationship between SET and SET-arranged based on students’ preference of STP and the relationship between SET and SET-arranged based on student’s DB Level. According to the result, manipulation of STP according to students’ preference of STP could influence a student’s evaluation. Students whose seats were prearranged by their seating preference had a higher evaluation of their teacher’s behavior and character than students who were randomly seated. When students were given opportunities to choose where to sit, the STP would be voluntary. The effect of STP might be diametrically opposite to the effect that occurred when individuals had no control over where they sat. That is to say, the affiliation motivation between participants could be interpreted or reflected by their expectation of proximity to the teacher [9,31,49]. On the contrary, the individual’s affiliation motivation could become unpredictable when the student had no control over where they sat.

Moreover, a significant relationship between the frequency levels of student’s disruptive behavior (the frequencies of students’ disruptive behavior were regrouped into low/ high to magnify the potential difference among students) and SET was found. The result corrected to the finding of the pilot study and revealed the relationship between SET and DB Level. The analysis of Treatment DB, which referred to the manipulation of STP according to student’s DB Level, consequently had its significance. Additionally, five sub-types of DB were found occurring frequently during the observation portion of this study. They were inattention, apathy, needless talking, annoying others, and disruption. Compared with the previous classification of student in-class disruptive behavior, the observations in this study found the students’ misbehavior categories more practical. These comprised personal behavior, such as promptness in arriving at class, inattentiveness, and language, technical behavior which includes the use of cell phones and iPods in class, and collaborative behavior such as receiving help on a test from another student or taking another person’s work and turning it in as their own. The observations also confirmed Humphrey’s finding of “successful interrupters”, which refers to students keeping quiet and waiting for the “best time” to disrupt class. The current research found, through recoding DB into DB Levels and manipulating STP, student’s disruptive behavior might be applied as a mediator to analyze the relationship between STP and SET. This finding is supported by a previous study, which shows that DB is reduced if a student is assigned to a seat close to the teacher [8,17].

Results also indicated the effectiveness of the Treatment DB after excluding for the impact of SET-individual tendency, SP Teacher and SP Teaching Content. The study found three covariates, SET individual tendency, SP Teacher and SP Teaching Content, was significantly related to SET Behavior and SET Character, which indicates that these three factors should be taken into considered when analyzing the causal relationship related to SET. However, among these three factors, SP Teacher has the highest strength for explaining SET. Previous study suggests that student behavior can shape a teachers’ impression of a student and the expectations they have for that student [51]. Many of the observed actions of teachers toward students were reactions to student behaviors, particularly DB [9]. People often use the implications of their own behavior as a basis for judgments and decisions to which this behavior is relevant [52,53].

Different perceptions and standards of DB could influence any misunderstanding between student and teacher, which would probably result in a predictably low SET. Additional, a significant relationship was found between student’s DB and student’s academic performance [52,54,55]. In China, a teacher’s perception of a student is strongly influenced by a student’s grade, GPA or test score. Thus, it is reasonable to presume that grades could be regarded as a significant mediator in the relationship among student’s DB, teacher’s perception of student and SET.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study pertains to the inadequate analysis of a specific factor. While the research examined the association between student-teacher proximity (STP) and in-class disruptive behavior (DB) among students, the analysis failed to account for the potential influence of other factors on the observed outcome. Subsequent investigations should consider incorporating additional variables, such as student-teacher rapport, teaching style, and classroom environment, as these factors may have a bearing on students' behavior within the classroom setting.

Furthermore, another limitation concerns the measurement and manipulation of STP. Although the current study computed STP based on the actual physical distance between students and teachers, it would be statistically advantageous to standardize STP by calculating it relative to peer comparisons. Future research endeavors could employ more advanced statistical techniques, such as multilevel modeling or structural equation modeling, to yield a more nuanced understanding of the impact of STP on student behavior.

A third limitation lies in the potential for observational bias during the assessment of student DB. The study employed Charles' classification system for in-class disruptive behavior, which may not be universally applicable across diverse cultural contexts. Additionally, the lack of clear operational definitions for each disruptive behavior category may introduce bias in the observations. To enhance the accuracy of behavioral assessments, future studies could employ multiple observation methods, including teacher ratings and peer assessments. Moreover, utilizing more precise and culturally relevant definitions of disruptive behavior would contribute to more reliable and valid findings.

Overall, addressing these limitations through future research endeavors will enable a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the relationship between STP, SET, disruptive behavior, and related factors within educational settings.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Walker, C. O., Winn, T. D., Adams, B. N., Shepard, M. R., Huddleston, C. D., & Godwin, K. L. (2009). Hope & Achievement Goals as Predictors of Student Behavior & Achievement in a Rural Middle School. Middle Grades Research Journal, 4(4), 17-30.View

Willoughby, M. T., Kupersmidt, J. B., Voegler-Lee, M. E., & Bryant, D. (2011). Contributions of Hot and Cool Self-regulation to Preschool Disruptive Behavior and Academic Achievement. Developmental Neuropsychology, 36(2), 162-180.View

Willoughby, M. T., Kupersmidt, J. B., & Voegler-Lee, M. E. (2012). Is Preschool Executive Function Causally Related to Academic Achievement? Child Neuropsychology, 18, 79-91.View

Mcclowry, S., Snow, D. L., Tamis-Lemonda, C. S., & Rodriguez, E. T. (2010). Testing the Efficacy of "INSIGHTS" on Student Disruptive Behavior, Classroom Management, and Student Competence in Inner City Primary Grades. School Mental Health, 2(1), 23-35.View

Levine, D. W., O’Neal, E. C., Garwood, S. G., & McDonald, P. J . (1980). Classroom Ecology: The Effects of Seating Position on Grades and Participation. Personally and Social Psychology Bulletin, 6(3), 409-412.View

Holliman, W. B., & Anderson, H. N. (1986). Proximity and Student Density as Ecological Variables in a College Classroom. Teaching of Psychology, 13(4), 200-203.View

Hall, E. T. (1966). The hidden dimension. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.View

Haghighi, M. M., & Jusan, M. M. (2012). Exploring Students Behavior on Seating Arrangements in Learning Environment: A Review. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 36, 287 – 294.View

Dong, Z., Liu, H., & Zheng, X. (2021). The influence of teacher student proximity, teacher feedback, and near-seated peer groups on classroom engagement: An agent-based modeling approach. PloS One, 16(1). View

Johnson, W., Mcgue, M., & Iacono, W. (2005). Disruptive Behavior and School Grades: Genetic and Environmental Relations In 11-Year-Olds. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(3), 391-405.View

Mehrabian, A., (1972). Nonverbal Communication. Behavioral Sciences, 31 (10). View

Charles, C. M. (2009). Building classroom discipline. Emeritus, SD: San Diego State University.View

Houghton, S., Wheldall, K., & Merrett, F. (1988).Classroom Behavior Problems which Secondary Teachers Say They Find the Most Troublesome. British Educational, 14(3), 297-312View

Infantino, J., & Little, E. (2007). Students’ Perception of Classroom Behavior Problems and the Effective of Different Disciplinary Methods. Educational Psychology, 25, 491-508. or Assessing Instructor Effectiveness. Business Education Digest.16,47-59.View

Brooks, D. M. (1978). Teacher behavior and character evaluation survey. Unpublished Instrument. Oxford, OH: Miami UniversityView

Black, S. (2007). Achievement by Design. American School Board Journal, 194(10), 39– 41.

Anguiano, P. (2011). A First-Year Teacher’s Plan to Reduce Misbehavior in the Classroom. Teaching Exceptional Children, 33(3), 52-55.

Ervin, R. A., Kern, L., Clarke, S., DuPaul, G. J., Dunlap, G., & Friman, P. C. (2000). Evaluating Assessment-based Intervention Strategies for Students with ADHD and Comorbid Disorders within the Natural Classroom Context. Behavioral Disorders, 25(4), 344–358.View

Charles, C. M. (1995). Building classroom discipline. London: Longman Pub Group.View

VanArsdale, S. K. & Hammons, J. O. (1995). Myths and Misconceptions About Student Ratings of College Faculty: Separating Fact From Fiction. Nursing Outlook, 43 (1), 33-36.View

Marsh, H. W., & Dunkin, M. J. (1992). Students' Evaluations of University Teaching: A Multidimensional Perspective. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Hartdbook of theory and research. New York: Agathon,Vol. 8, pp. 143-233.View

Centra, J. A. (1993). Reflective faculty evaluation. San Francisco, SF: Jossey-Bass.View

Engstrom, D. (1999). Correlations Between Teacher Behaviors and Student Evaluations in College Level Physical Education Activity Courses. Physical Educator, 56(2), 105-112.

Engstrom, D. (2000). Correlations Between Teacher Behaviors and Student Evaluations in High School Physical Education. Physical Educator, 57(4), 193.View

Quinn, D. M. (2020). Experimental evidence on Teachers’ racial bias in student Evaluation: The role of grading scales. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 42(3), 375–392. View

Morgan, W.D., & Vasche, J.D. (1978). An Educational Production Function Approach to Teaching Effectiveness and Evaluation. Journal of Economic Education, 9: 123-126. View

McGee, R. (1995). Faculty Evaluation Procedures in 11 Western Community Colleges. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 19, 341-348.View

Gump, S. E. (2007). Student Evaluations of Teaching Effectiveness and the Leniency Hypothesis: A Literature Review. Educational Review Quarterly, 30(3), 55-68.View

McPherson, M. A., Jewell, R. T., & Kim, M. (2009). What Determines Student Evaluation Scores? A Random Effects Analysis of Undergraduate Economics Classes. Eastern Economic Journal, 35(1), 34-51.View

Sommer, R. (1981). Twenty Years of Teaching Evaluations: One Instructor's Experience. Teaching of Psychology, 8, 223-226. View

Michael, A., McPherson, R., Todd, J., & Myungsup, K. (2009). What Determines Student Evaluation Scores? A Random Effects Analysis of Undergraduate Economics Classes. Eastern Economic Journal, 35, 37-51.View

Villard, H. H. (1973). Some Reflections on Student Evaluation of Teaching. The Journal of Economic Education, 5(1), 47–50.View

Mason, P. M., Steagall, J. W., & Fabritius, M. M. (1995). Student Evaluations of Faculty: A New Procedure for Using Aggregate Measures of Performance. Economics of Education Review, 14(4), 403–416.View

Safer, A. M., Fanner, L. S. J., Segalla, A., & Elhoubi, A. F. (2005). Does the Distance From the Teacher Influence Student Evaluations? Educational Research Quarterly, 28(3), 28-35. View

Soper, J. C. (1973). Soft Research on a Hard Subject: Student Evaluations Reconsidered. The Journal of Economic Education, 5(1), 22–26.View

Rodin, M., & B. Rodin. (1973). Student Evaluation of Teachers. The Journal of Economic Education, 5(1), 5–9.View

Nimmer, J. G., & Stone, E. F. (1991). Effects of grading practices and time of rating on student ratings of faculty performance and student learning. Research in Higher Education, 32(2), 195– 215.

Mateo, M. A. & Femandez, J. (1996). Incidence of Class Size on the Evaluation of University Teaching Quality. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 56(5), 771-778.View

Evans, M. & McNelis, R. (2000). Student evaluations and the assessment of teaching: What can we learn from the data? Washington, DC: Georgetown University.

Lin, W. Y. (1992). Is Class Size a Bias to Student Ratings of University Faculty? A Review. Chinese University of Education Journal, 20(1), 49-53.

Centra, J. A. (1993). Student evaluations of teaching: What research tells us. Reflective faculty evaluation: Enhancing teaching and determsining faculty effectiveness. San Francisco, SF: Jossey-Bass.

Silberman, M. L. (1969). Behavioral Expression of Teachers’ Attitudes towards Elementary School Students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 60, 402-407.View

Crump, H. B. (1974). An Analysis of the Verbal and Nonverbal Behaviors of Teachers toward Adjudicated Delinquents. Dissertation Abstracts International, 35(6), 3559-3560.

London, F. (1977). A Comparison of Black and White Observer Perceptions of Teacher Verbal and Nonverbal Behaviors toward Adjudicated Delinquents. In C. Achilles & R. French (Eds.), Inside classrooms: Studies in verbal and nonverbal communication. Danville, Ohio: Interstate Printers and Publishers.

Brooks, D. M. (2012). Classroom management. Unpublished class material. Oxford, OH: Miami University.

Brooks, D. M., Silvern, S. B., & Wooten, M. (1978). The Ecology of Teacher-Pupil Classroom Interaction. Journal of Classroom Interaction, 14, 39-45.

d'Apollonia, Sylvia, Abrami, & Philip C. (1997). Navigating student ratings of instruction. American Psychologist. 1198- 1208.View

Patrick, J., & Smart, R.M. (2006). An Empirical Evaluation of Teacher Effectiveness: the emergence of three critical factors. School of Applied Psychology. 165-178.View

Hamermesh, D. S., & Parker, A. (2005). Beauty in the classroom: instructors’ pulchritude and putative pedagogical productivity. Economics of Education Review, 24(4), 369–376.View

Brooks, D. M., & Rogers, C. J. (1981). Researching Pupil Attending Behavior within Naturalistic Classroom Settings. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, (3), 201. View

Good, (1983). Teachers Make a Difference. Journal of Teacher Education, 30, 52-64.View

Beaman, & Wheldall, (1994). Teachers' Use of Approval and Disapproval in the Classroom. An International Journal of Experimental Educational Psychology. 20 (4), 431-446. View

Albarraccin, & Wyer (2000). Influences of physical proximity to others on consumer choice. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 22(3), 418-423.

Little, E., Hudson, A., & Wilks, R. (2000). Conduct Problems Across Home and School. Behaviour Change, 7(2), 69-77. View

Little, E., Hudson, A., & Wilks, R. (2002). The Efficacy of Written Teacher Advice (Tip Sheets) for Managing Classroom Behavior Problems. Educational Psychology, 22, 251–266.View