Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour Volume 6 (2024), Article ID: JMHSB-188

https://doi.org/10.33790/jmhsb1100188Research Article

Intimate Introverts: Influence of Introversion on Self-Disclosure and Emotional Intimacy in Close Friendships

Naomi Battle, and Grace White*

Department of Psychology, University of Central Florida, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Grace White Ph.D., Department of Psychology, University of Central Florida, PO Box 161390, Orlando, FL 32816-1390, United States.

Received date: 09th April, 2024

Accepted date: 08th August, 2024

Published date: 10th August, 2024

Citation: Battle, N., & White, G., (2024). Intimate Introverts: Influence of Introversion on Self-Disclosure and Emotional Intimacy in Close Friendships. J Ment Health Soc Behav 6(1):188.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Social isolation is identified as a leading cause of loneliness, contributing to negative physical and mental health outcomes. Friendships developed or maintained in emerging adulthood can set the stage for social support and emotional well-being that individuals experience throughout their lifespan. Understanding the social and psychological mechanisms related to developing and maintaining these social connections may provide insight into solutions for many social problems. Introverted individuals tend to have fewer social contacts due to having a lower threshold for the energy required to fuel social interactions, impacting the development and maintenance of friendships. This study clarifies how trait introversion contributes to friendship intimacy, which may affect the strength and longevity of these important interpersonal relationships. Responses from 519 college-aged women from large southeastern university in the United States to the Friendship Qualities Scale, Emotional Self-Disclosure Scale, and the Aloof-Introverted subscale of the IPIP measure were analyzed. Results indicated that introversion had a significant negative correlation with both friendship qualities and emotional self-disclosure. Thus, introverts reported reduced levels of overall friendship intimacy. The current study offers a theoretical framework to shed light on factors contributing to the epidemic of loneliness among young adults. Consequently, we may gain insight into mitigating this issue by examining how individual characteristics impact interpersonal behaviors, resulting in diminished social and emotional connections.

Keywords: Introversion, Interpersonal Relationships, Friendship Qualities, Closeness, Emotional Self-Disclosure

Introduction

Interpersonal connections, particularly friendships, are important in providing social support that can significantly impact psychological development and stability across all life stages. This influence extends to reducing physical health risks and promoting positive mental health behaviors, especially in older adults [1]. From childhood, the nurturing of friendships contributes to a sense of belonging and aids in the formation of personal identity. As noted by Wrzus & Neyer [2], individuals often seek friends who share similar traits to reinforce their identity, personality, and emotional well-being. However, in today’s society, the ability to establish and maintain these vital social connections seems to be diminishing. Data from the Survey Center of American Life revealed that in 2021, only 16% of Americans relied on their friends for social support, a significant decrease from the 26% reported in 1990 [3]. This decline in reliance on friendships could be attributed to various factors, including cultural shifts that foster specific intrapersonal characteristics and social behaviors that may lead to increased social isolation.

Friendships are a cornerstone of social connection, needed for emotional well-being. According to social penetration theory, friendships go through four stages of development: orientation, exploratory affective exchange, affective, and stable exchange [4]. These stages are the equivalent of a relationship developing from acquaintances to “casual” friends and evolving to “close” and “best” friends if intimacy increases. Maintenance of friendships is described differently depending on whether the friend is considered “casual,” “close,” or “best.” “Casual” friendships rely mostly on proximity, while “close” and “best” friendships rely more on increased affection and interaction. Individuals are more likely to emotionally self-disclose and display relationship maintenance behaviors to foster friendship intimacy [4]. However, if intrapersonal factors or social behaviors inhibit emotional intimacy, it can be harder to receive much-needed social support and stress relief provided by friendships. The current study aims to explore how trait introversion influences closeness in friendship relationships, including emotional self-disclosure and friendship qualities, to better understand these social dynamics.

Personality and Friendship Development

For individuals who are temperamentally shy or socially aversive, also known as introverts, the development and maintenance of friendships can be particularly important as a protective factor for mental health. Social withdrawal has similarities to introversion in that both have the traits of solitary behavior and small friendship circles [5]. However, friendship quality or depth can be more psychologically significant than the number of friendships. Research on socially withdrawn adolescents revealed that having even one high-quality friendship provided noteworthy psychological benefits [5]. It can, therefore, be argued that elucidating the personality factors and social behaviors that foster friendship intimacy provides a framework for understanding these unique interpersonal connections and identifying at-risk populations [6].

Emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic, during which global mandates enforced physical and social isolation, the significance of the human need for social interaction and support became strikingly apparent [7]. Friends provide each other with social support, which functions like a safety net, relieving environmental and mental stressors [1]. For individuals whose personalities are highly social and gregarious, also known as extraverts, it is assumed that social contact and support are more necessary for them than their introverted counterparts [8]. However, social support has been shown to be equally important for highly extraverted and introverted individuals. In fact, introverted individuals could be at higher risk for loneliness due to the assumption that they do not need social interaction in the same manner as extraverts [8].

Social support received from interpersonal connections is multidimensional [1]. Some individuals in the support network can fulfill several roles, while others may fulfill just one. The network can be large with weaker connections or small with stronger connections. Introverts are more likely to have a smaller number of people fulfill multiple social support roles than several friends who serve only one function. The development and maintenance of digital friendships and social connections have increased due to the rise of social media and online networks. Online interactions have emerged as a significant way to initiate and sustain relationships [9], particularly for introverted individuals.

Those with introverted personalities and communication apprehension often find solace in online interactions, as it alleviates discomfort and social anxiety experienced in physical social settings [10]. Therefore, technology has become a useful resource in easing social tension and aiding introverts in developing meaningful social connections. Nevertheless, there is an ongoing question about whether introverts have the necessary social adeptness to sustain interpersonal connections. Therefore, it is important to investigate the characteristics associated with this trait and its influence on the quality of friendships. This may allow for the recognition and identification of any behavioral tendencies that could hinder the establishment of strong and lasting friendships.

Self-Disclosure in Friendships

Self-disclosure plays an essential role in fostering close-knit friendships. This means that individuals willing to share personal and emotional information contribute to deepening their social bonds. According to the Disclosure Processes Model, if the information shared is well-received in the initial stages of social interaction, communication is more likely to persist, ultimately leading to increased intimacy [11]. Self-disclosure can be an integral part of friendship intimacy as it fosters connectedness, can illicit social support, and provides opportunities for psychological authenticity. These elements also align with many psychological factors in overall well-being.

Shyness and its associated traits can lead to a lower level of self disclosure. This may be due to the individual’s negative perception of social interactions and can prevent closer social relationships [12]. Shyness is associated with low psychological security, leading shy individuals to withhold personal information to feel “safe.” This behavior contributes to a lower rate of self-disclosure among individuals with this trait. Hence, it may undermine aspects of friendship intimacy that are needed for social connectedness and mental health.

Individuals with social anxiety can also have difficulty with self disclosure, especially in the initial stages of friendship [13]. Whil in most instances, befriending another person can relieve stress, individuals with high levels of social anxiety can become more stressed in these interactions. This can make it harder for these individuals to self-disclose and form close friendships. However, the actor-partner interdependence model posits that those with social anxiety are more likely to befriend and become close with another person who has a similar level of social anxiety and that they influence each other within the friendship [14,15]. It is important to recognize that self disclosure plays a key role in nurturing deeper social connections. As a result, we delve deeper into the characteristics and behaviors that hinder this process to better understand and address them.

Insecurity can also greatly impact how much we open up to others. Research has shown that people are more likely to share personal information with their friends than with strangers, but this can change when it comes to insecurities [16]. The fear of exposing vulnerabilities and potentially damaging their close relationships can make individuals hesitant to disclose their insecurities to their friends. Interestingly, the "passing strangers" effect [17] can come into play in these situations, as disclosing insecurities to strangers may feel less risky. Specifically, strangers are not intimately familiar with the person's life and are not a constant presence to remind them of their insecurity. Overall, friendship intimacy thrives on emotional self-disclosure, which builds strong and lasting connections. These bonds have far-reaching effects on our emotional well-being and psychological resilience throughout our lives. Subsequently, empirical explorations of these concepts remain necessary to develop practical recommendations to address mental health crises surrounding issues of loneliness in society.

Current Study

The current study aims to investigate the intersection of trait introversion and friendship intimacy in young adults using elements of the social penetration theory [4] and the Disclosure Processes Model [11] to help contextualize friendship processes. It should be taken into consideration how important friendships are in shaping identity in emerging adulthood, as well as the social and mental benefits friendships form across the lifespan [1,5]. Friendship dynamics can give insight into how people respond to changes within themselves and in their environment. However, there is a paucity of research exploring these social connections beyond childhood and adolescence. The current study may provide additional context to how introverts navigate their close friendships in emerging adulthood. This may further clarify whether this group is at risk for social isolation or dysfunction in their social connections.

Gender differences often influence the nature of friendships, with female friendships typically involving more intimacy and interdependence than male friendships [18]. This expectation for greater intimacy can pressure both parties to provide support, potentially straining the relationship. Additionally, a lack of social support from friends can make it more challenging for women to navigate social environments, such as college, where women are expected and compete to belong to different social groups. The significance of female friendships cannot be understated, as they play a central role in female development. Thus, we focused on exploring these connections among an all-female sample.

Social penetration theory [4] posits that friendships evolve through four distinct stages, with relationships gradually developing as individuals cautiously assess each other to determine the compatibility of the friendship. As relationships move through the four stages, the friendship deepens in closeness and intimacy. We further argue that characteristic friendship qualities and self-disclosure depend not only on closeness but also on personality trait introversion and its associated behaviors like communication apprehension. While closeness can be a function of the length of the friendship, this is not always an indicator of intimacy, especially with introverts. Consequently, we hypothesized:

1. Introversion will be significantly associated with aspects of friendship relationship dynamics or qualities. Specifically, we predicted scores on the Friendship Qualities Scale (FQS) [19], including the subscales of companionship, conflict, help, security, and closeness and the Aloof-Introverted subscale of the International Personality Item Pool–Interpersonal Circumplex Scale (IPIP-IPC) would correlate, indicating an association between introverted personality and friendship characteristics.

2. Introversion will be significantly associated with self-disclosure in friendship relationships. Specifically, we expected the scores on the Emotional Self-Disclosure Scale (EDSDS) [20] and the Aloof-Introverted subscale of the IPIP-IPC would correlate, indicating an association between levels of introversion and depth of emotional self-disclosure in friendships.

Self-disclosure is an essential aspect of denoting friendship intimacy, as the Disclosure Processes Model states that positive disclosure exchanges in the initial stage of relationships foster more communication in later stages, helping sustain social relationships [11]. By taking introversion’s influence on interpersonal relationships into account, we can investigate intrapersonal factors and social behaviors on friendship quality.

Method

Participants

519 women from a large southeastern university in the United States, whose average age was 23.27 years old (SD = 5.83), responded to study measures. The sample was mostly white 71.7% (n= 372). Other races included in the sample were Black 14.3% (n= 74), Asian 3.9% (n= 20), Native American. 4% (n= 2), Hawaiian Pacific Islander .2% (n= 1), and mixed race 9.2% (n= 48). Two participants did not respond to this item. 32.9% (n= 171) of the sample also identified as Hispanic/Latina. Regarding friendship characteristics, the average length of friendships was approximately 7 years (M = 86.24 months, SD = 67.36). 62.8% (n= 326) of friendships began before adulthood. 84.8% (n= 440) of friendships were same sex, with participants indicating that they shared the same gender identity with their friends.

Procedure

Prior to collecting data, the measures and study procedures were approved through the institutional review board (IRB). Participants were recruited from a large southeastern university and through social media flyers. Students earned extra credit or course credit. Participants were required to be at least 18 years old and have a friendship of at least 6 months. Before participants answered any survey questions, they completed an informed consent and agreed to participate. The survey was conducted online through Qualtrics. Participants completed the Friendship Qualities Scale, Emotional Self-Disclosure Scale, Personal Report of Communication Apprehension Scale, and the Aloof-Introverted subscale of the International Personality Item Pool–Interpersonal Circumplex Scale, and answered demographic questions about age, race, ethnicity, and friendship characteristics.

Materials

Friendship Intimacy: We operationalized friendship intimacy as the relational attributes on the Friendship Qualities Scale (FQS) and Emotional Self-Disclosure Scale (ESDS). FQS has 23 questions “concerning the friendship qualities of conflict, companionship, help, security, and closeness” on a 5-point Likert Scale, 1 “not at all true” to 5 “really true” [19]. High scores on the conflict (α = .77) subscale can be indicators of friendships that have elevated levels of disagreements and tension, thus possibly reflecting poor friendship quality. High scores on the companionship (α = .72), help (α = .84), security (α = .58), and closeness (α = .80) subscales can be indicators of healthy relationship behaviors, thus characterizing constructive relationship qualities.

The Emotional Self-Disclosure Scale (ESDS) has 40 questions “concerning the extent to which you have discussed these feelings and emotions with your friend” on a 5-point Likert Scale, scored 0 “I have not discussed this topic with my friend” to 4, “I have fully discussed this topic with my friend” [20]. A high score on any of the eight subscales (depression, happiness, jealousy, anxiety, anger, calmness, apathy, and fear) would indicate higher levels of self disclosure on each of the subscale topics. However, an overall index of emotional self-disclosure can also be computed. The overall scale's reliability coefficient, Cronbach’s alpha, was .97.

Introversion. To explore the trait introversion, we used the aloof-introverted subscale of the International Personality Item Pool– Interpersonal Circumplex Scale (IPIP-IPC). IPIP-IPC has 32 items that describe the participant’s current self and trait behaviors on a 5-point Likert Scale, with 1 meaning “Very inaccurate” and 5 meaning “Very accurate.” Items 1, 9, 17, and 25 are the subscale Aloof-Introverted. A high score would indicate high levels of introversion [21]. Scores range from 4 to 20. The reliability coefficient of this subscale was .74.

The Personal Report of Communication Apprehension Scale (PRCA 24) is 24 statements “concerning feelings about communicating with others” on a 5-point Likert Scale, with 1 meaning “Strongly Disagree” and 5 meaning “Strongly Agree” [22]. Scores are obtained by adding all four subscales (Group discussion (α = .79), Meetings (α = .87), Interpersonal (α = .80), and Public Speaking (α = .82)) together. Scores below 51 represent those with very low communication apprehension (CA) levels and indicate a low level of introversion. Scores between 51 and 80 represent the average amount of CA, and scores above 80 equal a high level of CA, with the latter indicating a high level of introversion.

Data Analytic strategy

SPSS software version 28 was used to complete the descriptive and inferential data analyses. Assumptions of univariate normality were met for skewness and kurtosis (skewness < 3, kurtosis < 10) for the measures of aloof-introversion IPIP-IPC, Personal Report of Communication Apprehension Scale (PRCA-24), the Friendship Qualities Scale (FQS) and the Emotional Self-Disclosure Scale (ESDS) before testing the hypotheses. We conducted Pearson correlation analyses to assess the relationships between introversion IPIP-IPC scores and scores on the Friendship Qualities Scale and the Emotional Self-Disclosure Scale. We also completed independent sample t-tests to compare low and high-scoring groups on introversion to each other on the friendship intimacy variables. The alpha level was set to .05.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

We examined the connection between our primary study variables and the length of reported friendship to investigate whether time in the relationship was affected by personality or had a significant connection to friendship intimacy attributes. Friendship length (in months) was found to have a significant positive correlation to emotional self-disclosure (r = .11, p = .028) but not introversion (r = .07, p = .154). Friendship length was not significantly correlated with the FQS subscales of friendship, conflict (r = .04, p = .204), companionship (r = -.001, p =.492), or closeness (r = .06, p = .126). There were, however, significant positive correlations for help (r = .14, p = .003) and security (r = .12, p = .009). These findings indicate that length of friendship may have some small notable links to aspects of relational attributes that contribute to friendship intimacy. Nonetheless, it is not strongly related to these friendship qualities, nor is time in relationship a function of personality, specifically introversion, in these data.

To explore the convergent validity of trait introversion and communication apprehension, scores on the IPIP-Introversion and the PRCA were correlated. Findings revealed trait introversion was significantly associated with both the overall communication apprehension global score (r = .21, p < .001) and aspects of communication apprehension, including group discussion (r = .22, p < .001), meetings (r = .21, p < .001), and interpersonal (r = .16, p < .001). However, it was not correlated with the public speaking scale (r = .03, p = .277). The small magnitude of the correlations suggests that trait introversion and communication apprehension lack strong convergence and may be distinct characteristics, at least as measured by the PRCA and the IPIP-IPC in these data. Thus, we did not further investigate the PRCA as an equivalent trait, or interchangeable trait, with trait introversion.

Hypothesis Testing

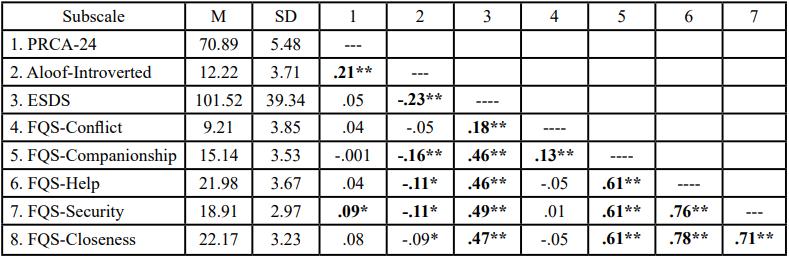

Hypothesis 1. Correlation coefficients for the primary hypotheses are shown in Table 1. Hypothesis 1 predicted that introversion had a significant association with friendship qualities, which would influence friendship intimacy. Scores on the subscales of the Friendship Qualities Scale and the aloof-introverted subscale of the IPIP-IPC would indicate this relationship. An inverse association was found between introversion and friendship qualities, with significant negative correlations on subscales of companionship (p < .001), help (p = .006), security (p = .008), and closeness (p = .016). Conflict was not significantly correlated with introversion (p = .150). These results suggest that the higher an individual’s level of introversion, the less likely they were to report engagement in or expression of, certain friendship maintenance and intimacy behaviors. The magnitude of the effects was small.

Table 1: Inter-Correlations between Introversion, Friendship Qualities, and Emotional Self-Disclosure

Given the mean score in the sample on the IPIP-IPC introversion scale (M = 12.22, SD = 3.71) indicated that there were moderate to low levels of introversion present overall, we were concerned about the restriction in the score range towards the lower end of the scale for introversion in the correlational analyses. To further examine the impact of introversion on our variables of interest, we separated the sample responses into individuals with higher introversion scores and individuals with lower introversion scores. Thus, the sample was split into participants with scores 10 or below on the aloof-introversion scale (n= 169), indicating less introversion, grouped as “1” and those with scores above 10 (n= 348), indicating more introversion, grouped as “2.” A preliminary independent-sample t-test was conducted to confirm that there was a difference in introversion between these two groups. Their mean introversion IPIP-IPC scores revealed that the low introversion group (M = 7.95, SD = 1.74) and high introversion group (M = 14.30, SD = 2.42) were indeed significantly different in their average introversion scores t(515) = -30.51, p < .001, 95%CI [-6.76, -5.94], d = -2.86. We then used these high and low introversion groups to compare participant responses on the friendship intimacy variables.

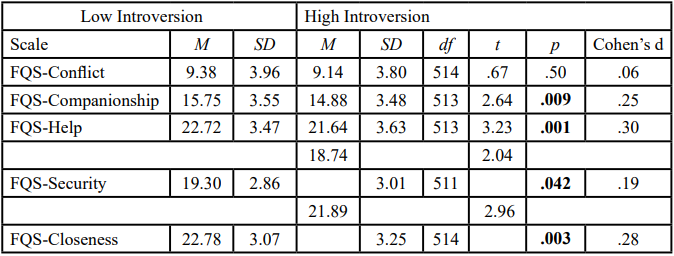

We report the coefficients and test statistics from these t-tests in Table 2. When comparing these two groups on friendship qualities, it was found that those with the lowest levels of introversion in the sample were significantly different from the “high” introversion group in that they engaged in more positive friendship qualities, with a significant difference existing in their average scores on companionship, help, security, and closeness and no significant difference with conflict.

Table 2. Differences Between Women with Low Introversion versus High Introversion on the Friendship Qualities Scale

Our findings confirm the first hypothesis, revealing a significant relationship between introversion and friendship relationship maintenance behaviors. Specifically, individuals with higher levels of introversion reported fewer positive relationship maintenance and intimacy behaviors or feelings, such as companionship, help, security, and closeness. These effects, though small to moderate based on Cohen’s d effect size conventions [23], are nonetheless significant, shedding light on the impact of introversion on friendship intimacy.

Hypothesis 2. It was predicted that introversion has a significant association with emotional self-disclosure, which would influence friendship intimacy. Scores on the aloof-introverted subscale of the IPIP-IPC and the ESDS were correlated. Similar to hypothesis one, we found a significant negative correlation between introversion and emotional self-disclosure (r = -.23, p < .001). These results suggest that increases in introversion scores were associated with decreases in reported emotional self-disclosure.

An independent-sample t-test also confirmed differences between the low and high introversion scoring groups on emotional self-disclosure. Those with lower levels of introversion, on average, had significantly higher self-disclosure scores (Low Introversion: M = 112.68, SD = 37.11, High Introversion: M = 96.08, SD = 39.35); t(507) = 4.55, p < .001, 95%CI [9.43, 23.76], d = .43. These findings confirmed our second hypothesis that introversion has a significant impact on emotional self-disclosure in friendships. This had a moderate effect overall.

Discussion

Friendships are an important source of interpersonal connection and social support [1,25]. Nonetheless, little research explores the dynamics and processes in friendships after childhood and adolescence [15,19]. This lack of focus on friendship processes in adulthood may be partly due to the increase in romantic dating and marital relationships, which are also an important source of support and emotional stability in adulthood. The primary aim of this study was to explore the impact of intrapersonal characteristics, like introversion on friendship intimacy. Using elements of the social penetration theory [4] and the Disclosure Processes Model [11], we anticipated that introversion would impact friendship development and maintenance behaviors as well as emotional self-disclosure, which are foundational components of friendship intimacy. This research also focused specifically on female friendships, as these social connections are typically characterized by high levels of self-disclosure and relational intimacy [18].

As predicted, our findings indicated that women with higher levels of introversion reported fewer friendship intimacy behaviors. This included engaging in lower levels of self-disclosure and expressing fewer feelings of closeness and security in their friendships. The average levels of introversion in the sample were moderate to low. Nonetheless, it is important to note that approximately 67% of the women in the sample were categorized into the “high” introversion group with scores greater than 10 on the aloof-introverted subscale of the IPIP-IPC. Comparing the “high” introvert to the “low” introvert groups on their introversion scores indicated a large effect size (d = -2.86). Thus, there may be meaningful differences between these individuals as it relates to their intrapersonal experiences of introversion. Even at moderate levels, introversion appears to have a measurable negative impact on friendship intimacy, including self-disclosure. The effects of introversion on friendship attributes were mostly moderate.

Previous research aligns with these results, as introverted individuals have tended to be socially reserved [6]. Researchers have interpreted this reservation to mean that introverts perceive friendship development as being more gradual, using metaphors like “friendship blossoming” when describing their relationships, which may imply more cautious approach [6]. In particular, introverted individuals can have qualities related to shyness and social anxiety. These traits are associated with decreased self-disclosure and greater tension during social interactions [12,13]. The stress that social anxiety can bring to an intimate interaction like self-disclosure can heavily discourage an individual from deepening an early friendship [13]. This can cause them to become avoidant and be more likely to lessen the amount of self-disclosure they engage in to avoid the discomfort. Ultimately, these behaviors can have a detrimental effect on friendship intimacy, as supported by the current study. These findings also suggest that interventions targeting introverted individuals could focus on enhancing emotional self-disclosure skills. Creating an environment that can reduce stress levels and make individuals feel safer in self-disclosing can be a step forward in improving social relationships and creating more intimate friendships.

Prior research may also help to explain the decrease in self-disclosure to long-term friends. Kim et al. [16] posit that insecurities can sometimes cause individuals to not self-disclose to those closest to them. Not wanting to be associated with their insecurities, individuals may opt not to self-disclose to avoid being around a constant reminder of their apprehension. Given that our sample was college-aged women in emerging adulthood this age group may still be grappling with self-discovery and identity formation. Even though they reported an average length of friendships of over 7 years, these early years of adulthood, including the early 20s, may be a ripe period for insecurities and uncertainties. Consequently, they may be experiencing insecurities that they are not yet willing to share with their long-term friend groups. This effect on self-disclosure introduces another level of complexity to interpersonal relationships, as an individual can choose to self-disclose to their innermost social network in certain contexts and avoid self-disclosure in other contexts. As introverts are more likely to have smaller social support networks, the possible negative effects of self-disclosing their insecurities to their closest friends could be seen as more risky than beneficial.

Implications and Future Directions

Early adulthood can be a life stage full of disruptive transitions. The emergence of COVID-19 and the subsequent lockdowns resulted in physical and social isolation for many, including those who were already vulnerable to loneliness [24]. Women are frequently stereotyped as having large, intimate friend groups [18]. As such, they are treated as being at lower risk for loneliness. However, for introverted women, this depiction may not accurately capture their real-life experiences. The current study provides insight into these experiences that show a lower level of social connectedness for introverted women compared to their less introverted female peers.

Friendships are among many vital social relationships that help young adults maintain good mental health. Social inclusion is a good indicator of how individuals receive and maintain mental health support [25]. Individuals with strong social support systems, stable employment, and education have better opportunities and abilities to maintain their mental health than those with weaker social ties and NEET (Not in Employment, Education, or Training) status. Nonetheless, for introverts the ability to solicit much-needed social support may be inhibited or undermined by their characteristic behavioral tendencies or insecurities, resulting in decreased friendship intimacy. Hence, identifying these behaviors may be necessary to develop appropriate interventions for this at-risk population.

The current study can provide important information about aspects of social processes among young adult women. However, given that the sample was female and mostly white, these findings may not generalize to male friendships and individuals of other ethnicities. Therefore, future research must explore these friendship processes for introverted males and within more diverse populations. Moreover, a longitudinal examination of friendship processes over time may provide additional clarification of these relationship dynamics that are not captured by short-term, cross-sectional reports of friendships. Most of the effects found in this study were also small to medium, which may limit our ability to fully discern the practical impact of the measured factors on behavior. Future research may address these concerns through more rigorous real-world measurements rather than self-report data.

Conclusion

The current study brings attention to the concerning levels of social isolation and disconnection experienced by introverted women. In today's society, there is a misconception that women always have access to strong, close-knit friend groups for social support, while men are celebrated for being the strong, silent type [18]. However, loneliness is on the rise for both men and women [7]. The lack of social connections can have detrimental effects on mental health and society as a whole. It is important to understand that friendships play a primary role in mitigating loneliness and social isolation. Individuals who feel lonely can react in ways that are both harmful to themselves and society. This study highlights the need for mental health professionals and policymakers to consider individual personality traits and diverse social experiences of women when developing interventions to combat loneliness. It's essential to create environments where introverts feel comfortable engaging with others and where genuine emotional connections can be made to foster healthy social relationships. Addressing the increasing loneliness in our society may be the key to resolving many of the social and mental health crises faced by today’s culture.

Declarations

The authors have no competing interests to declare relevant to this article's content.

The authors declare that neither they nor any immediate family member has a significant conflict of interest nor any potential bias against another product or service discussed in our paper.

References

Asante, S., & Karikari, G. (2022). Social relationships and the health of older adults: An examination of social connectedness and perceived social support. Journal of Ageing and Longevity, 2(1), 49–62.View

Wrzus, C., & Neyer, F. J. (2016). Co-development of personality and friendships across the lifespan. European Psychologist, 21(4), 254–273.View

Cox, D. A. (2021, June 8). The state of American friendship: Change, challenges, and loss. American Survey Center. View

Rose, S. M., & Serafica, F. C. (1986). Keeping and ending casual, close and best friendships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 3(3), 275–288. View

Barzeva, S. A., Richards, J. S., Veenstra, R., Meeus, W. H. J., & Oldehinkel, A. J. (2021). Quality over quantity: A transactional model of social withdrawal and friendship development in late adolescence. Social Development.View

Nelson, P. A., & Thorne, A. (2012). Personality and metaphor use: How extraverted and introverted young adults experience becoming friends. European Journal of Personality, 26(6), 600– 612.View

Demarinis, S., (2020). Loneliness at epidemic levels in America. Explore, 16(5), 278–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. explore.2020.06.008View

Card, K.G., & Skakoon-Sparling S. (2023). Are social support, loneliness, and social connection differentially associated with happiness across levels of introversion extraversion? Health Psychology Open, 10(1). View

Larson, L. (2021). Social media use in emerging adults: Investigating the relationship with social media addiction and social behavior. Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research, 26(2),228–237.View

Punyanunt-Carter, N. M., De La Cruz, J., & Wrench, J. S. (2018). Analyzing college students’ social media communication apprehension. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 21(8), 511–515.View

Chaudoir, S. R., & Fisher, J. D. (2010). The disclosure processes model: Understanding disclosure decision making and post disclosure outcomes among people living with a concealable stigmatized identity. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 236–256. View

Li, L., Chen, Y., & Liu, Z. (2020). Shyness and self-disclosure among college students: the mediating role of psychological security and its gender difference. Current Psychology.View

Ketay, S., Welker, K. M., Beck, L. A., Thorson, K. R., & Slatcher, R. B. (2018). Social anxiety, cortisol, and early-stage friendship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(7), 1954–1974. View

Kashdan, T. B., & Wenzel, A. (2005). A transactional approach to social anxiety and the genesis of interpersonal closeness: Self, partner, and social context. Behavior Therapy, 36(4), 335–346. View

Van Zalk, N., Van Zalk, M., Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2011). Social anxiety as a basis for friendship selection and socialization in adolescents’ social networks. Journal of Personality, 79(3), 499–526. View

Kim, S., Liu, P. J., & Min, K. E. (2021). Reminder avoidance: Why people hesitate to disclose their insecurities to friends. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(1), 59–75. View

Rubin, Z. (1975). Disclosing oneself to a stranger: Reciprocity and its limits. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 11, 233–260. View

Felmlee, D., Sweet, E. & Sinclair, H.C. (2012). Gender rules: Same- and cross-gender friendship norms. Sex Roles, 66, 518– 529.View

Bukowski, W. M., Hoza, B., & Boivin, M. (1994). Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence: The development and psychometric properties of the Friendship Qualities Scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11(3), 471–484.View

Snell Jr, W. E., Miller, R. S., & Belk, S. S. (2013). The Emotional Self-Disclosure Scale (ESDS). Measurement Instrument Database for the Social Science.View

Markey, P. M., & Markey, C. N. (2009). A brief assessment of the interpersonal circumplex: The IPIP-IPC. Assessment, 16, 352-361.View

McCroskey, J. C. (2005). An introduction to rhetorical communication. (9th ed). Prentice Hall.View

Privitera, G. (2019). Essential statistics for the behavioral sciences. (2nd edition). Sage Publications.View

Dingle, G., Han, R., & Carlyle, M. (2022). Loneliness, belonging, and mental health in Australian university students pre- and post-COVID-19. Behaviour Change, 39(3), 146-156. View

Filia, K., Menssink, J. M., Gao, C. X., Rickwood, D., Hamilton, M., Hetrick, S., Parker, A. G., Herrman, H., Hickie, I. B., Sharmin, S., McGorry, P. D., & Cotton, S. (2021). Social inclusion, intersectionality, and profiles of vulnerable groups of young people seeking mental health support. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57(2), 245–254.View