Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour Volume 6 (2024), Article ID: JMHSB-190

https://doi.org/10.33790/jmhsb1100190Research Article

Addressing Adverse Childhood Experiences in the Latino Community: An Innovative Parental Education Program -Strikeout Toxic Stress!

Irán Barrera*, and Vrinda Sharma

Department Social Work Education, Fresno State University, 5310 N. Campus Drive M/S PHS 102, Fresno, CA-93740, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Irán Barrera, Professor, Department Social Work Education, Fresno State University, 5310 N. Campus Drive M/S PHS 102, Fresno, CA-93740, United States.

Received date: 03rd October, 2024

Accepted date: 28th October, 2024

Published date: 30th October, 2024

Citation: Barrera, I., & Sharma, V., (2024). Addressing Adverse Childhood Experiences in the Latino Community: An Innovative Parental Education Program -Strikeout Toxic Stress!. J Ment Health Soc Behav 6(1):190.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) harm childhood behavior and well-being. Often leading to long-term health outcomes during adulthood, ACEs are associated with an increased risk of chronic diseases and mental health problems. Screening tools like the ACE questionnaire help identify at-risk individuals, highlighting the need for targeted interventions. Parental education programs aim to mitigate the effects of ACEs by empowering parents with knowledge and skills. In this context, a twelve-module learning series intervention program called Strikeout Toxic Stress! was designed to enhance parental engagement in learning about ACEs through activity books. We evaluated this novel approach by assessing the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ-Parent form) and a modified ACE questionnaire (ACE-Q) for Latino parents in Fresno, California. We evaluated data collected before and after intervention through paired sample t-tests to determine the statistical differences between responses.

The evaluation revealed significant improvements in parenting practices post-intervention. Particularly in Latino communities, where disparities exacerbate ACE incidence, targeted interventions are crucial for mitigating long-term effects. While sample homogeneity and size limitations exist, innovative initiatives like this promise to foster healthier outcomes, enhancing the well-being of our youth. Further long-term studies could help health policymakers to adapt this innovative program to other communities.

Keywords: Childhood Well-being; Mental Health; Community health initiatives; Parenting Intervention Programs; Family Engagement Strategies

Introduction

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) critically impact childhood behavior and lifestyle quality. ACEs are preventable, potentially traumatic events that occur among individuals from 0 to 18 years old and are often associated with sociodemographic factors related to adverse social, economic, and cultural environments [1].

The association between poor health outcomes -the risk of chronic diseases and mental illness- and experience of multiple adverse events in childhood has been well documented since 1998 when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published the CDC-Kaiser study [2].

The consensus of the literature on ACEs indicates that children who experience maltreatment, such as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, have an increased risk of mental health problems, substance use disorder, depression, suicide attempts, and risky sexual behavior [3,4].

Like many other population traits, variances among communities exist, leading to fluctuating risks of ACE across different socioeconomic and educational strata and ethnic groups. Children from minor communities, including Hispanics, Blacks, and American Indians; children from lower-income homes; and children from single-parent households are more likely to experience ACEs at an early age compared to non-deprived communities [5].

In the US, 63.9% of surveyed adults reported at least one ACE and 17.3% had suffered four or more ACEs [6]. ACEs became a short- and long-term public health concern due to adverse health outcomes during adulthood [3]. Furthermore, as disparities among the population increase, so does the incidence of ACEs. Policy development to address ACEs could reduce -or prevent- negative long-term impacts on children's adulthood.

One critical aspect of addressing childhood adversity is accurately identifying patients through screening, often achieved through comprehensive surveys or questionnaires [7]. The ACE questionnaire (ACE-Q) and its many versions were designed to cover conflicted and adverse themes in different populations, including children, adults, and parents. Examples of ACE-Q are the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), an annual random telephone ACE-Q developed for US adult data collection [6], and the World Health Organization (WHO) ACE International Questionnaire (ACE IQ) [8]. Basic ACE-Q are designed for people older than 18 years and determine exposure to eight types of ACEs. Questions are divided into modules that cover physical, sexual, and emotional abuse; peer violence; witnessing intra-familiar or collective violence; household substance abuse; or mental illness. ACE-Q has demonstrated that exposures to ACEs converge to increase the risk for a wide range of mental illnesses, addictions, and medical diseases [9].

Regarding the expansion of ACE disease, parental education could be the answer to reducing the prevalence of ACEs: Giving parents the knowledge that prevents ACE among children and adolescents from disadvantaged communities can demonstrate how practical tools can change family norms, parents' attitudes, and behavioral intentions [1,10].

To begin unraveling the relationship between parental emotional education and the impact of ACE on their children, our team developed an intervention program called Strikeout Toxic Stress! This twelve-module learning series program was designed to educate parents about the adverse effects of ACE on their children by using a learning series/coloring activity book [11]. We chose this method based on empirical evidence showing that adult coloring reduces depressive symptoms and anxiety [12]. With a strong focus on Latino families, we conducted a pilot study that included sixteen participants from rural and peri-urban regions of Fresno City, California, during the SARs-Co-2 lockdown [11].

In the present study, we analyzed the potential benefits of the Strikeout Toxic Stress! program in the Latino community of Fresno. Two cohorts of Spanish-speaking parents from different areas of Fresno City completed two complementary questionnaires, the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ-parent form) and ACE-Q modified, before and after completing the Strikeout Toxic Stress! Program. We aimed to elucidate whether this tailored educational material improves emotional care and parenting involvement in children's lives.

Methodology

Data collection

The APQ-parent form comprises 42 Likert-scale questions. Each question has a scale response structure, ranging from never (1) to always (5). It measures five dimensions of parenting relevant to the causes of externalizing problems for children. Each subscale or category evaluates parenting involvement, positive parenting, poor monitoring/supervision, inconsistent discipline, and corporal punishment, with six additional questions to establish other disciplinary practices. We surveyed in Spanish, and all participants signed an informed consent form.

While the original ACE-Q is a self-reported measure to identify childhood experiences of abuse and neglect, we developed a modified ACE-Q adapted to measure parents' perceptions of ACEs. We revised and adjusted the questions to avoid confusion arising from the complexity of the initial ACE-Q, which included several double-barreled questions. Consequently, seven specific questions (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 9) were divided into separate inquiries (1a, 2a, 3a, 4a, 5a, 7a, 7b, and 9a) to enhance the survey's clarity. All instruments were administered in Spanish [see Supplementary Information for the English version (SS1) and Spanish (SS2)].

Participants

From November 2020 to September 2021, two distinct cohorts (n = 37) of Latino parents underwent assessments using the APQ-Parent form and a modified ACE-Q. The initial dataset comprised responses from twenty-two participants, sourced from the Fresno Center (FC), collected between November and December 2020. Subsequently, the second cohort consisted of fifteen participants from the Centro La Familia (CLF) dataset, surveyed between August and September 2021. We administered surveys at designated dates and times before and after participants participated in the parental intervention program (detailed below), with each session typically lasting 1.5 to 2 hours.

Intervention

Strikeout Toxic Stress! is a twelve-module learning series program (hereafter referred to as the intervention) focused on parental engagement in learning about ACEs. Using coloring activity books, Latino parents learned about the negative impact of ACEs on child development. The intervention included self-esteem, respect, encouragement, protection, communication, rest, affection, thoughtfulness, bouncing back, love, health, and success as individual and family values. We designed coloring activity books to address each topic, assess the parental role in the child(ren) 's ACEs, and educate them about the adverse health outcomes related to ACEs. To reinforce this strategy, we encourage parents through different activities, including descriptions of communication styles between parents and their children, role-playing exercises, providing the pros and cons of unhealthy communication, and examples of positive communication and its role in fostering healthy parent-child relationships.

Analysis Conducted

To evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention, parents completed two complementary questionnaires, the APQ-Parent form and a modified version of the ACE-Q, before and after the intervention.

We conducted comparisons of both the mean and median values for each sub-scale. However, to ascertain the effectiveness of the intervention, we prioritized the determination of statistical significance through the t-test.

Analysis

All the participants were required to complete the survey at the beginning and end of the intervention. We evaluated each questionnaire subscale before and after the program using a paired sample t-test. The pre-test evaluations served as the baseline data, and the post-test allowed us to directly compare the participants' responses between two time periods, which can provide a clear indication of a change.

Our null hypothesis states that no difference exists between the scores recorded before and after the program implementation. The paired sample t-test provides an estimate of the significance of the difference between the means of the participants' responses before and after.

Results

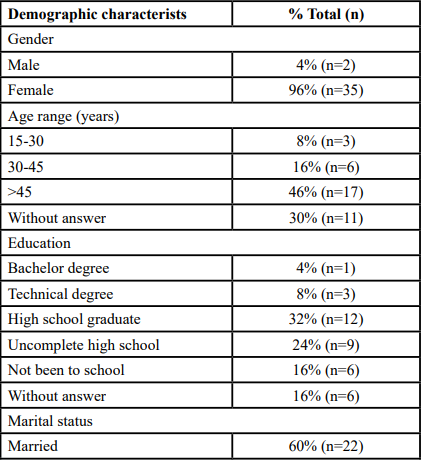

Thirty-seven Latino parents answered a Spanish version of the APQ-Parent form and a modified version of the ACE questionnaire. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of this population. From the total of participants, 22 answers were collected from the Fresno Center (FC) dataset, and 15 were from the Centro La Familia (CLF) dataset.

While most participants resided in Fresno City (84%), 6 participants lived in the rural area (16%) of Fresno City. This population had significantly more females (96%) and married participants (60%). As shown in Table 1, the most common family structure involved 2-4 children (68%), with an income prevalence under $25,000 (57%).

Alabama Parenting Questionnaire

All the participants answered the survey at the beginning and end of the intervention (see Tables 2 and 3).

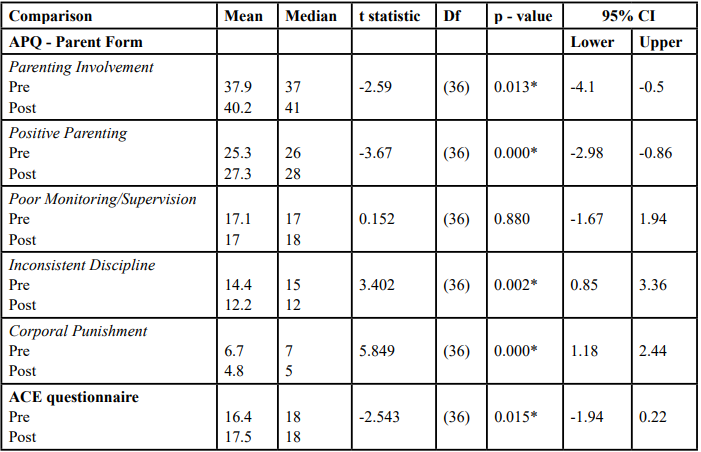

The Parenting Involvement sub-scale consisted of 10 questions regarding parent's participation in the child's life. The minimum score of this sub-scale is 10, while the maximum is 50. We observed increased parents' involvement after finishing the program (Pre-intervention: 37.9 vs. Post-intervention: 40.2, p < 0.05).

Table 2. Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ - Parent Form) and modified-ACE questionnaire. Pre and Post interention Scores

The Positive Parenting sub-scale consisted of 6 questions identifying positive reinforcement (praise and material rewards) of parenting styles. The minimum score of this sub-scale is 6, while the maximum is 30. A higher score in this sub-scale indicates more positive parenting than a lower score. After finishing the program, we observed a significant increase in positive parenting scores (Pre-intervention: 25.3 vs. Post-intervention: 27.3, p < 0.05).

The Poor Monitoring/Supervision sub-scale consisted of 10 questions that identified parents' attention to what the child was doing. The minimum score of this sub-scale is 10, while the maximum is 50. In this case, a higher score would indicate poorer monitoring/ supervision of the child. We did not observe a significant difference between the mean responses on the poor monitoring/supervision score between pre- and post-intervention (Pre-intervention: 17.1 vs. Post-intervention: 17.0, p > 0.05).

The Inconsistent Discipline sub-scale consisted of 6 questions identifying the application of disciplinary rules erratically or unpredictably. The minimum score of this sub-scale is 6, while the maximum is 30. A higher score would indicate higher inconsistency in discipline. There was a statistically significant difference between the mean responses on the inconsistent discipline score between pre-and post-program (Pre-intervention: 14.4 vs. post-intervention: 12.2, p < 0.05), meaning that, after finishing the program, parents were more consistent with their disciplinary style.

The Corporal Punishment sub-scale consisted of 3 questions identifying a physical punishment form. The minimum score of this sub-scale is 3, while the maximum is 15. A higher score would indicate higher corporal punishment. We observed significant differences between corporal punishment after and before the program (Pre-intervention: 6.7 vs. post-intervention: 4.8, p < 0.05), showing a reduction in corporal punishment.

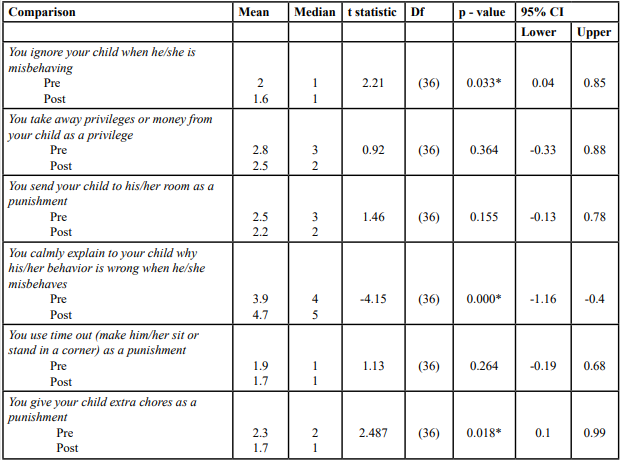

The APQ-Parent form includes six questions excluded from the five analyzed sub-scales. Each provides information on Other Discipline Practices (Table 3) item-by-item basis. After finishing the program, we observed a significant decrease in parental neglect of child misbehaving (Pre-intervention: 2.0 vs. post-intervention: 1.6, p < 0.05), an increase in time toward explaining children misbehaves (Pre-intervention: 3.9 vs. Post-intervention: 4.7, p < 0.05), and a decreased in the punishment with extra chores (Pre-intervention: 2.3 vs. Post-intervention: 1.7, p < 0.05). However, taking away privileges, sending their child(ren) to the room, and using time out (e.g., making their child(ren) sit or stand in a corner) as punishments did not change after finishing the program (Table 3).

ACE Questionnaire

We have created an adapted version of the ACE-Q, comprising 18 true-or-false questions with scores ranging from 0 to 18 (SS1 and SS2). We compared total scores before (ACE pre-questionnaire) and after (ACE-post-questionnaire) the parental intervention program. A higher score indicates a higher ACE literacy among the parents.

We observed a significant increase in the mean score of the ACE pre-questionnaire compared to the ACE post-questionnaire (Pre-intervention mean 16.4 vs. post-intervention 17.5, t-test: 2.54, p-value: 0.015). These results showed an increase in ACE literacy among parents.

Discussion

ACEs encompass traumatic experiences during childhood and adolescence, including physical, psychological, and sexual abuse, as well as neglect and exposure to domestic violence. The growing body of evidence regarding the lasting harmful effects of ACEs includes mental health disorders and poor health outcomes [13]. While the biological mechanisms are unknown, researchers suggest that childhood experiences modify the structure and function of the brain and, in the case of ACEs, trigger abnormal stress responses and cognitive impairments during adulthood [14].

To change the future of children harmed by paternal misconduct, we developed an innovative approach through our twelve-module learning series program, Strikeout Toxic Stress! Our goal is to educate parents about the negative impact of ACEs on their children through a coloring activity book [11].

To evaluate the program's effectiveness, we assessed parental responses about their relationship with their children before and after the Strikeout Toxic Stress! Intervention using the APQ-Parent form and modified ACE-Q. Our findings reveal that four sub-scales of the APQ-Parent form exhibited significant differences between pre-and post-program assessments, showing increased parent involvement and positive parenting among participants and reduced inconsistent and corporal punishment. We are confident that this translated into a positive shift in parental attention to the child, the time invested in explaining misbehavior and reducing extra chores as punishment. Furthermore, our modified ACE-Q, designed to assess parents' views on child abuse, revealed differences between assessments. This outcome suggests an increased recognition of ACEs among participants after the intervention and a significant influence of the program on parental awareness.

In the US, the Latino population is an underprivileged community with socioeconomic, educational, and cultural disparities. The incidence of ACEs increases as these disparities grow deeper. It is urgent to change the future of these children. Early identification and targeted interventions are tailored to the needs of vulnerable children during their formative years [15]. Furthermore, educational policy must be focused on parental behavior to avoid or reduce the negative impact of ACE on their children.

While the transmission mechanism of ACE through generation remains unclear, the consequences of parental ACEs are clear, highlighting the urgency for comprehensive public health policies to protect future generations [2,16].

Initiatives based on parent education awareness of ACEs, with a cultural community base, improve children's social-emotional development, allowing them to grow in a safe environment [17].

Limitations and Future Perspectives

While our study demonstrated that the Strikeout Toxic Stress! program modified parental involvement, turning it into positive parenting, it is essential to acknowledge the limitations of our research.

While the sample shows homogeneity, sample size and the lack of a control group are the main limitations of this study. Although the sample size of 37 participants limits the generalizability of the findings, it offers a preliminary insight into the potential impacts of the parental education intervention. Small effect sizes may hold clinical relevance, mainly when consistent changes are observed across multiple participants. However, the modest sample size reduces statistical power, making it difficult to detect subtle differences and increasing the risk of Type I and Type II errors.

In this sample, high mean scores on some scales before and after the intervention suggest that parents were already performing well before the program, resulting in a "ceiling effect" that restricts the ability to detect significant improvements. Nevertheless, the statistically significant results indicate consistent, albeit minor, enhancements among parents.

A sample of this size may struggle to detect moderate effects, particularly in studies involving diverse outcomes like changes in sentiment or behavior. Our findings may not represent a broader population, so future studies should aim to replicate these findings in more extensive and long-term, more diverse populations to confirm the efficacy and scalability of this educational approach, where variations in socioeconomic status, cultural background, and education level can significantly influence outcomes.

Our study offers preliminary insight into the potential impacts of parental education intervention. This innovative approach holds promise in mitigating the adverse effects of childhood adversities, thereby fostering healthier outcomes for future generations.

Conclusion

The negative impact of ACEs during adulthood triggers vast adverse health outcomes, from mental disorders to diverse comorbidities. Initiatives focusing on parental education could create a more promising future for our children. The Strikeout Toxic Stress! Parental program is a unique prevention program aimed at reducing ACEs.

Declarations

Competing interests:

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding: The authors did not receive financial support for research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: Dr. Irán Barrera conceived and designed the Strikeout Toxic Stress! Protocol, performed data collection and execution of the research experiment and wrote and revised the final manuscript for submission.

Vrinda Sharma conducted the statistical analyses and data interpretation.

Ethics statement: This study was approved by Fresno State University Human Subjects Committee under Fresno State's University Review Board.

Data Availability: Data is not made available to the public to protect study participant privacy.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Mónica Faut for their services as Medical Editor.

List of Abbreviations

ACEs: Adverse Childhood Experiences

ACE-Q: Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire

APQ: Alabama Parenting Questionnaire

BRFSS: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CLF: Centro La Familia

FC: Fresno Center

References

Narayan, A. J., Lieberman, A. F., & Masten, A. S., (2021). Intergenerational transmission and prevention of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Clin Psychol Rev. 85: 101997. View

Boullier, M., & Blair, M. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences. Paediatrics and Child Health, 28(3), 132–137. View

Hunt, T. K. A., Slack, K. S., & Berger, L. M. (2017). Adverse Childhood Experiences and Behavioral Problems in Middle Childhood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 67, 391. View

Liming, K. W., & Grube, W. A. (2018). Wellbeing Outcomes for Children Exposed to Multiple Adverse Experiences in Early Childhood: A Systematic Review. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 35(4), 317–335. View

Mersky, J. P., & Janczewski, C. E. (2018). Racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences: Findings from a low-income sample of US women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 480–487. View

Swedo, E. A., Aslam, M. V., Dahlberg, L. L., Niolon, P. H., Guinn, A. S., Simon, T. R., & Mercy, J. A. (2023). Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences Among U.S. Adults — Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011–2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 72(26), 707– 715.View

Jacob, G., Van Den Heuvel, M., Jama, N., Moore, A. M., Ford Jones, L., & Wong, P. D. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences: Basics for the paediatrician. Paediatrics & Child Health, 24(1), 30–37. View

Gette, J. A., Gissandaner, T. D., Littlefield, A. K., Simmons, C. S., & Schmidt, A. T. (2022). Modeling the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire-International Version. Child Maltreatment, 27(4), 527–538.View

Zarse, E. M., Neff, M. R., Yoder, R., Hulvershorn, L., Chambers, J. E., & Chambers, R. A. (2019). The adverse childhood experiences questionnaire: Two decades of research on childhood trauma as a primary cause of adult mental illness, addiction, and medical diseases. Cogent Medicine, 6(1), 1581447.View

Webster, E. M., (2022). The Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences on Health and Development in Young Children. Glob Pediatr Health. 26:9:2333794X221078708.View

Barrera, I., Mendoza, C., & Crawford, M. (2022). Juntos: Changing Knowledge and Prevention of Adverse Childhood Experiences Among Latinos During a Pandemic. Academia Letters. View

Flett, J. A. M, Lie, C., Riordan, B. C, Thompson, L. M, Conner, T. S, & Hayne, H. (2017). Sharpen your pencils: Preliminary evidence that adult coloring reduces depressive symptoms and anxiety. Creativity Research Journal, 29(4), 409–416. View

Yeo, G. H., Lansford, J. E., Hirshberg, M. J., & Tong, E. M. W. (2024). Associations of childhood adversity with emotional well-being and educational achievement: A review and meta analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 347, 387–398. View

Su, Y., D’Arcy, C., Yuan, S., & Meng, X. (2019). How does childhood maltreatment influence ensuing cognitive functioning among people with the exposure of childhood maltreatment? A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 252, 278–293.View

Matjasko, J. L., Herbst, J. H., & Estefan, L. F. (2022). Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences: The Role of Etiological, Evaluation, and Implementation Research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 62(6 Suppl 1), S6–S15. View

Grafft, N., Lo, B., Easton, S. D., Pineros-Leano, M., & Davison, K. K. (2024). Maternal and Paternal Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Offspring Health and Wellbeing: A Scoping Review. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 28(1). View

Giunta, H., Romanowicz, M., Baker, A., O'toole-Martin, P., & Lynch, B. A. (2021). Positive Impact of Education Class for Parents with Adverse Childhood Experiences on Child Behavior. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 15(4), 431–438. View