Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour Volume 6 (2024), Article ID: JMHSB-191

https://doi.org/10.33790/jmhsb1100191Research Article

Body Image Self Assessments of College Students who Engage in "Body Dating" or Hookups

Sandra Terneus1*, and Hannah K. Atkinson2

1 Professor, Department of Counseling & Psychology, Tennessee Tech University, Matthews Hall, Rm. 166, United States.

2 KdG, A Division of Shive-Hattery, Inc., St Louis, Missouri, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Sandra Terneus, PhD, NCC, LMFT, LPC, LCPC, Professor, Department of Counseling & Psychology, Tennessee Tech University, Matthews Hall, Rm. 166, United States.

Received date: 16th October, 2024

Accepted date: 20th November, 2024

Published date: 22nd November, 2024

Citation: Terneus, S., & Atkinson, H. K., (2024). Body Image Self Assessments of College Students who Engage in "Body Dating" or Hookups. J Ment Health Soc Behav 6(2):191.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Body image is a multidimensional construct that incorporates the complexities of persons' perceptions of their physical appearance and attitudes about their own body [1]. The cultural ideals of beauty continue to be difficult to achieve [2] as people have tried to change and align their bodies to these esthetical standards [3] of thinness and sexiness for females and muscularity for males. During a post-COVID environment, researchers have noted an increased concern over body image and appearance anxiety since the sedentary COVID isolation may have stifled the pressure of being mentally consumed with one’s weight, shape, and appearance. Further complexities in returning to campus included a return to hookups which is identified as two people meeting to engage in casual sex without emotional commitments. This latest social norm of hookups implies that the first encounter requires a physically appealing first impression which exacerbates the anxiety, depression, and at-risk behaviors associated with body image and appearance. Therefore, the purpose of the study was to ascertain college students’ perception of body image via silhouettes of increasing weight and shapes. Participants were asked to identify the silhouette which represented themselves, the silhouette which they desired to be, the silhouettes they believed each gender (male and female) would find most attractive as well as the most common silhouette in their culture. For the most part, the results concur with the literature except for the desire for an athletic and toned female image as desired among female participants as opposed to the once-desired thinness. This matches male respondents desire for an athletic female silhouette as well as the athletic and muscular male profile. Perhaps, an athletic toned physique will be the new desired body image for and of both genders.

Introduction

Literature has documented extensive research regarding body image, appearance anxiety, and the accompanied mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression, eating disorders, obsessive compulsive disorders, among youth and adults across various cultures and countries. Regarding college students in the United States, Leavitt [4] had suggested that undergraduate college students were vulnerable to the development of eating disorders, disordered eating, and body image concerns. Disordered eating is a term to describe a range of irregular eating behaviors which caused significant distress in a person’s life that may or may not warrant a diagnosis of a specific eating disorder [5]. Although it is common to have body image concerns with eating disorders, a person does not have to have a diagnosable eating disorder to maintain a distorted negative body image. College counseling centers have been reporting that among anxiety and depression, body image and appearance anxiety are one of the most frequently reported concerns of college students. In the 2020 Annual Survey, college counseling centers reported that eating disorders and body image issues were reported at 13% in 2020 and increased to 14% in 2021 [6,7]. Thus, the issues of eating disorders, appearance, and body image and subsequently, self esteem, anxiety, depression, and life satisfaction are still pertinent trends to investigated.

Study of Literature

Literature continually advocates that social media, and the fashion/ celebrity industries have negatively influenced youth and young adults on their perceptions about their bodies. In addition, Leavitt [4] revealed unhealthy behaviors which were normalized and expected among American college students such as: 1) avoid eating before going out, 2) fasting for later alcohol consumption, 3) fasting in order to wear apparel, 4) over-exercising, 5) hearing or sharing comments about other people’s bodies, and 6) wishing to have an eating disorder to maintain a desired thinness. Unfortunately, the fashion industry, movies, and social media, have created a platform for body and appearance comparisons, but have also glamorized eating disorders [4].

Closely related to body image concerns is appearance anxiety and appearance investment. According to Cash, Melnyk, & Hrabosky [8] appearance investment is the extent to which one engages in appearance self-evaluative or appearance improvement behaviors such as attributing one’s weight as a measure of self-identity and the effort of appearance improvements through cosmetics, diet, apparel, and exercise. Sarwer et al. [9] found that female college students maintained a greater appearance investment as well as greater internalization of social media’s portrayal of beauty. Female undergraduates who have reported more distorted body image perceptions have stronger investments in their appearance than males and contended with higher levels of anxiety and depression as accompanied by disordered eating patterns and low self-esteem [10]. Henniger, Edwards, and Terneus [11] found that female college students reported significantly higher levels of cognitive distortion, body image awareness during sex, and appearance investment than male college students. Accordingly, Yan’s [12] study found that female college students, thus, also suffered from appearance-anxiety problems, and have identified the main causes of college students’ appearance anxiety as the “pursuit of beauty” “defects in appearance” as well as the halo effect or cognitive bias of attractiveness within the social environment, and thus, the resulting lack of self-confidence.

Grossbard et al. [13] proposed that although both genders experienced body image and associated self-esteem issues, female self-esteem was contingent on thinness while male self-esteem was contingent on muscularity. Hoyt and Kogan [14] examined body image issues in conjunction with relationships among female and male college students and found that females indicated significantly higher dissatisfaction with their own body image than males. Contrarily, males indicated significantly greater dissatisfaction with their relationship status and overall sex life than did females. Thus, this may indicate that female college students equated life and relationship satisfaction upon their assessment of their own body image, and males equated life and relationship satisfaction upon the quality of sex within their relationships [15]. Hoyt & Kogan [14] poised that appearance was prioritized of more importance for females because males typically emphasized physical attractiveness of their partners significantly more so than females in partner selection.

As research has recently documented the influence of the pandemic on society, Ferrara et al. [16] found that during the pandemic, college students, especially male students, abandoned or reduced physical activity practice and nutrition while increasing social media use. Thus, the results indicated a direct association between very low frequency of physical activity and increased sedentary time and between change in dietary style and increased body mass (weight gain). Zhou and Wade [17] concurred and noted a significant increase in weight concerns, disordered eating, and negative affect among female college students after the onset of COVID. However, due to the isolation during COVID, one wonders if the appearance anxiety and body image concerns lessened due to a lack of social interaction and potential scrutiny perceived by both genders. This would prove worthy of further investigation.

Rubio [18] contends that one of college students’ initial goals to campus life is to fit in and acclimate to the campus norms, and there is the expectation that students will conform with a certain image and behavior. One of the expectations or norms of college life appears to be hooking up or body dating (casual sex without commitment). Hooking up occurs at alcohol-supported social functions such as fraternity and sorority functions in which college students who are strangers or brief acquaintances meet to engage in varying sexual encounters without commitment of a relationship. Hooking up has increased in frequency and as an accepted form of a quick social encounters among college students due to the instant gratification of sex without the potential emotional upheaval of a relationship; hence the emphasis on body dating [15,19,20]. Some college students, who continue hookup encounters, are satisfied with casual sex; however, for others, consenting to a hookup encounter carries hope in establishing a continued and future relationship with that partner. Usually, this first encounter of hooking up refines the decision making process on the evaluation of the first impression...if one’s body and appearance are considered attractive enough by another. Unfortunately, research has revealed that the aftermath of casual sex has left negative and regretful responses by both genders, including accentuated body image issues.

Thus, research has continued to show a trend in distorted thinking focused on appearance on body image issues, especially, on female college students. In research of body image and self-esteem in college students, Lowery et al. [21] found that females consistently held negative body image perceptions and poor attitudes as compared to males. Females also perceived themselves with larger discrepancy between their real self-image and their ideal body image [22]. Therefore, the focus of this study was to ascertain college students’ perceptions of body weight and shape associated with their self image and attractiveness.

Methodology

Participants

The participants were college undergraduate students enrolled in psychology classes at a southeastern university. The demographics of the sample of undergraduate college students (N=85) revealed a mean age of 18, gender selection revealed 33% were males and 67% were females, and racial indicators revealed 88% White, 4% Asian, 4% First Nations People, 3% Black, and 1% Other. Regarding relationship status, 64% of males and 46% of females were single, 36% of males and 49% of females were in a relationship, and 0% of males and 5% of females were married.

Materials/Measure

Current weight charts include images ranking from morbid obesity to underweight body images. However, there is currently a lack of an image chart which includes muscular physique on a continuum scale. Therefore, this survey contained an original body image weight chart depicting silhouettes ranging from morbid obesity to overly muscular physiques. The silhouettes ranged in sizes using the classification of weight status by body mass index (BMI) such as Obesity: class 3, Obesity: class 2, Obesity: class 1, Obesity, Overweight, Healthy, Underweight, and muscular physiques such as Athletic Gymnast, Weightlifter, and Body Builder for females and Athletic Soccer Player, Football Player, Weightlifter, and Body Builder for males. Professional body builder trainers and nurses confirmed the silhouettes as reflective of varying weights and forms. Darkened or shadowed silhouettes were used to omit appearance issues such as facial features (see Appendix A). The participants were asked to read questions and respond relative to the silhouettes. Descriptive statistics were used to used to discern the participants top three responses.

Procedure

As research had been following society’s responses to body image and cosmetic reconstruction as well as the increased concerns in eating behavior during and returning to a post pandemic environment, this study’s focused was on college students’ perceptions of body image. After obtaining IRB approval, a survey was distributed to undergraduate psychology students using Qualtrics as the survey engine. Participants were asked to select the silhouette which closely matched their own physique, which figure they preferred, which figure they believed males and females would prefer, and which figure was the most common in their culture. In addition, participants were asked follow-up questions regarding body satisfaction and body scanning.

The Results

When participants were asked if they were satisfied with their own figure, 54% of males and 54% of females indicated that they were not satisfied. When participants were also asked if they would trade in a year of their life to have an ideal figure, 38% of males and 32% of females indicated that they would do so. As a follow-up, participants were asked how many years that they would be willing to trade in for the ideal figure which resulted in responses that 61% of males would not trade, 25% of males would trade 1 to 2 years of life for the ideal figure, and 14% would trade 3 to 5+ years of life to have the ideal figure, while 67% of females would not trade, 26% of females would trade 1 to 2 years of life for the ideal figure, and 7% would trade 3 to 5+ years of life for the ideal figure.

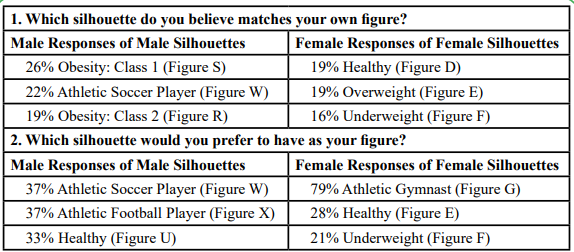

The following table provides data regarding self-assessment and preferences by gender. Male participants were asked to view a male silhouette ranging from classification of weight via BMI and muscular builds of Athletic Soccer Player, Football Player, Weightlifter, and Body Builder. Similarly, female participants were asked to view a female silhouette ranging from classification of weight via BMI and muscular builds of Athletic Gymnast, Weightlifter, and Body Builder.

Although male respondents indicated self-perceptions of having a heavier body mass, the desired preference of male respondents indicated the more muscular and healthy silhouettes. Female respondents reported self-perceptions ranging from Underweight to Overweight silhouettes as matching their own physique; however, female respondents desired preference indicated a jump of 79% for the toned Athletic Gymnast while maintaining Healthy and Underweight as desired silhouettes. These responses were concurrent with literature in that males preferred muscular builds; however, it also appeared that even though some of the female respondents desired a silhouette which was considered Underweight, the pronounced choice for the toned Athletic Gymnast body image may be emerging for females’ preference. It was interesting to note that both genders had preferences for the Healthy and Athletic builds except for some female participants who indicated a preference of Underweight.

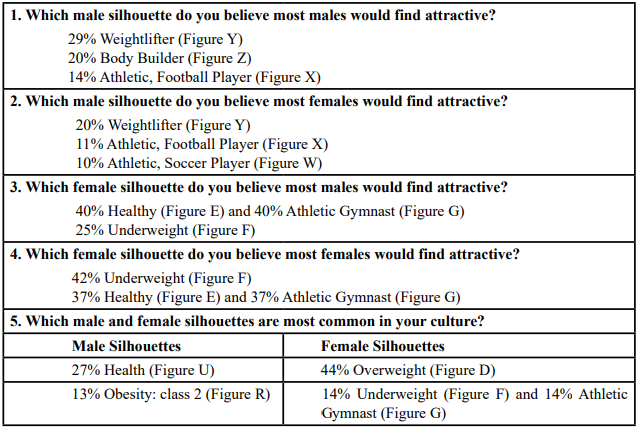

The following table was to investigate the belief that participants have regarding what other people would identify as attractive. In other words, female participants were asked which silhouettes they believed other females and males would find attractive. Similarly, male participants were asked which silhouettes they believed other males and females would find attractive.

As noted above, males and females perceived a muscular male silhouette as attractive as indicated in preferences for Weightlifter, Football Player, and Soccer Player; this outcome for a desired muscular form for males concurs with the literature. However, regarding identification of the attractive female silhouette, there appeared to be a small discrepancy in the belief that females would find the Underweight female silhouette as attractive (42%) and the belief that males would find the Healthy female silhouette as attractive (40%); therefore, the question poised were females more concerned with being identified as attractive to other females or were the participants following the social norm of thinness as attractive for females. It was interesting to note the belief that males would find the Healthy and Athletic silhouettes as attractive for females since the social norm has been thinness. Regarding the most common male and female silhouettes as perceived in their culture, it appears that both genders have represented weight sizes ranging from the Overweight and Healthy classifications as the norm for their culture which also parallels their perceptions of their own physique in Question 1.

Discussion

As earlier stated, Grossbard et al. [13] proposed that although both genders experienced body image concerns as females desired thinness and males desired muscularity. These results concur with the overall literature with the exception of the growing perception of females’ preference (n=79%) for an athletic and toned female image as opposed to thinness. This concurs with male respondents indicating as a preference for an athletic female silhouette as attractive as well as for an athletic and muscular male profile.

Clearly, it is alarming to know that young adults would be willing to trade life away for an image which they possibly believe would bring them happiness, acceptance, and life satisfaction. Such a definitive desire may tie into the reasons for a growing cosmetic and reconstructive surgery as a profitable business. However, research on post-surgical and treatment would warrant further investigation.

A limitation of the study was the small sample size as well as college students as participants. In addition, as an investigative study, statistical analysis was restricted to selection frequency. Also, the silhouettes were original and non-standardized. Since literature consistently equates the beginning of body image concerns occurring in adolescents, additional studies inclusive of age range, ethnicity, and sample size could enhance current body image trends.

Since body image seems pervasive in social media and with hookup encounters on college campuses, additional questions were posed in the survey. When asked if physical attraction was a high priority in considering dating someone, 39% of males and 95% of females indicated yes, but 61% of males and 49% of females indicated no. However, when asked if having a relationship included someone who was physically attractive to the participant and vice versa, 86% of males and 84% of females indicated yes. It can be assumed that although physical attraction may not be the priority, it is a reciprocal necessity in a relationship.

Relevant to hookup behaviors, participants were asked if they scanned a person’s body parts when they met someone for the first time. Male participants revealed that 37% indicated that they scanned everyone, 27% scanned only females, 0% scanned other males, and 36% did not scan. Female participants revealed that 53% scanned everyone, 2% scanned females, 12% scanned only males, and 33% did not scan. In comparison, participants were asked if they scanned a friend’s body parts. Male participants revealed that 29% indicated that they scanned friends, 11% scanned only female friends, 0% scanned other male friends, and 60% did not scan friends. Female participants revealed that 33% scanned friends, 4% scanned female friends, 2% scanned only male friends, and 61% did not scan friends. Since both genders scanned others, this would suggest that body scanning may need further research, i.e., are those individuals who scan aware of their scanning behavior upon others, and if so, is there an evaluative outcome? Are people aware when they are being scanned, and how does body scanning of others impact a relationship? In addition to Leavitt’s [4] list of unhealthy behaviors, is body scanning also a behavior being normalized and expected among college students? Thus, with hookup encounters on college campuses and post pandemic research indicating weight changes and an increase on appearance, body scanning may also be a component to be examined further.

In conclusion, although the overall results of this study concurred with the literature, some responses indicated a detour from the social norm of thinness for a female as indicated by a preference for the athletic and toned female silhouette as attractive. As this sample was a small size (n=85) and stereotypically gender silhouettes were used, further research would help to validate this trend. In addition, further studies may also help to explore body scanning’s impact upon others (friends, strangers, how often), as well as body dating behaviors on college campuses and the effect of mental health of those who engage in hookups or body dating since recent literature has suggested was remorse was experienced by both genders, and especially, the distortions and need to harbor the desire to trade more than a year of one’s life in exchange to have an ideal figure. Recent post-COVID research has indicated that eating and body concerns are re-escalating; one ponders if this is a by-product of transitioning back into a social environment as opposed to the COVID’s isolation lifestyle which prohibited encounters and thus, stifled the anxiety and concerns of weight and appearance. As college counseling centers are still posting waiting lists for counseling services, the Center for Collegiate Mental Health has reported anxiety to be the most common presenting concern [23], and Gorman et al. [6] found that 13% of the student sample reported eating/body image concerns. Thus, it would be apparent that normalized unhealthy behaviors of body scanning and body dating/hookups may have facilitated the increase anxiety and investment of body appearance repertoire as well as unwanted sexual encounters for college students in the United States.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Thompson, j. K., & Schaefer, L., (2019). Thomas F. Cash: A multidimensional innovator in the measurement of body image; Some lessons learned and some lessons for the future of the field. Body Image. 31:198-203. View

Murnen, S. K. (2011). Gender and body image. In T. F. Cash & L. Smolak (Eds.), Body image: A handbook of science, practice, and prevention (2nd ed.) (pp 173-179). NY: Guilford. View

Goswami, S., Sandeep, S., & Sachdeva, R. (2012). Body image satisfaction among female college students. Industrial Psychiatry Journal; Mumbai, 21(2), 168-172. View

Leavitt, N. (2021, March 23). Eating disorders, disordered eating, and body image within college students and media, News, Illinois State University, Normal, IL USA https://news. illinoisstate.edu/2021/03/eating-disorders-disordered-eating-and-body-image-within-college-students-and-media View

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders,(5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author.View

Gorman, K. S., Bruns, C., Chin, C., Fitzpatrick, N. Y., Koenig, L., LeViness, P., & Sokolowski, K. (2020). Annual Survey 2020, Association for University College Counseling Center Directors. View

Healthy Minds Network. (2022). Healthy minds study among colleges and universities, year, 2021–22 data report. Healthy Minds Network, University of Michigan, University of California Los Angeles, Boston University, and Wayne State University. View

Cash, T. F., Melnyk, S. E., & Hrabosky, J. I. (2004). The assessment of body image investment: An extensive revision of the Appearance Schemas Inventory. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 35(3), 305-316.View

Sarwer, D. B., Cash, T. F., Magee, L., Williams, E. F., Thompson, J. K., Roehrig, M., Tantleff-Dunn. S., Agliata, A. K., Wilfley, D. E., Amidon, A. D., Anderson, D. A., Romanofski, M., (2005). Female college students and cosmetic surgery: An investigation of experiences, attitudes, and body image. Plastic Reconstructive Surgery, 115(3), 931-938.View

Vartanian, L E., Giant, C L., & Passino, R. M., (2001). “Ally McBeal vs Arnold Schwarzenegger”: Comparing mass media, interpersonal feedback and gender as predictors of satisfaction with body thinness and muscularity. Social Behavior and Personality, 2, 711-723.View

Henniger, N. E., Edwards, D., Terneus, S. K., (2024). Body Image Cognitive Distortions during Sexual and Nonsexual Situations: Differentiating the Effects on Appearance Investment, Tennessee Counseling Association Journal, 9(1), 33-46.

Pan, Y., (2023). Analysis of the Causes of Appearance Anxiety of Contemporary College Students and Its Countermeasures, Journal of Medical and Health Studies, 4(4), 45-53. View

Grossbard, J., Lee, C. M., Neighbors, C., & Larmier, M. E., (2009). Body image concerns and contingent self-esteem in male and female college students. Sex Roles, 60(3-4), 198-207. View

Hoyt, W. D., & Kogan, L. R., (2001). Satisfaction with body image and peer relationships for males and females in a college environment, Sex Roles, 45(3/4), 199-215.View

Terneus, S. K., (2022). College Students’ Perceptions of Chaperones in Opposition to Hookups or “Body Dating”. In M. Shelley, V. Akerson, & I. Sahin (Eds.), Proceedings of IConSES 2022 International Conference on Social and Education Sciences (pp. 146-156), Austin, TX, USA. ISTES Organization. View

Ferrara, M., Langiano, E., Falese, L., Diotaiuti, P., Cortis, C., & De Vito, E. (2022). Changes in Physical Activity Levels and Eating Behaviours during COVID-19 Pandemic: Sociodemographic Analysis in University Students. International Journal of Environment Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5550. View

Zhou, Y., & Wade, T. D. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on body-dissatisfied female university students. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54(7), 1283-1288. View

Rubio, A. (2018, October 19). College students continue to struggle with body image, The Daily Toreador, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 7940. View

Bogle, K. A. (2008). Hooking Up: Sex, dating, and relationships on campus. New York University Press. View

Garcia, J.R., Reiber, C., Massey, S. G., & Merriwether, A. M., (2013). Sexual Hookup Culture: A Review. Review of General Psychology.16(2),161–176. View

Lowery, S. E., Kurpius, S. E. R., Befort, C., Blanks, E. H., Sollenberger, S., Nicpon, M. F., & Huser, L. (2005). Body image, self-esteem, and health-related behaviors among male and female first year college students, Journal of College Student Development, 46(6), 612-623. View

Lokken, K., Ferraro, F. R., Kirchner, T., & Bowling, M. (2003). Gender differences in body size dissatisfaction among individuals with low, medium, or high levels of body focus. View

Center for Collegiate Mental Health. (2023, January). 2022 Annual Report (Publication No. STA 23-168) View