Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour Volume 6 (2024), Article ID: JMHSB-192

https://doi.org/10.33790/jmhsb1100192Review Article

Maintaining Psychological Wellness in Young Cancer Patients and Survivors: An Awareness and Information Paper by The Global Alliance for Mental Health Advocates (GAMHA)

Fatimah Lateef1*, Jocelyn I Ilagan2, Fardous Hosseiny3, Cho-chiong Tan4, Porsche Poh5, and Gabriel Lungu6

1 Professor, Senior Consultant, Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore.

2 Faculty, Policy and Health Systems Specialist, Masters in Social Work, Technical Consultant, Dept of Health and Development Partners (USAID, UNFPA), Asian Seminary for Christian Seminaries, Phillipines.

3 Institute of Mental Health Research at the Royal, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

4 Neurology-Psychiatry. Institute of Medicine, Far Eastern University Dr Nicanor Reyes Medical Foundation.

5 Executive Director, Silver Ribbon, Singapore.

6 Mental Health Officer/ Nursing Officer, Ministry of Health HQ, Ndeke House, Lusaka, Zambia.

Corresponding Author Details: Fatimah Lateef, FRCS (A&E), MBBS, FAMS (Em Med), Professor, Senior Consultant, Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Outram Road, 169608, Singapore.

Received date: 31st October, 2024

Accepted date: 29th November, 2024

Published date: 02nd November, 2024

Citation: Lateef, F., Ilagan, J. I., Hosseiny, F.,Tan, C. C., Poh, P., & Lungu, G., (2024). Maintaining Psychological Wellness in Young Cancer Patients and Survivors: An Awareness and Information Paper by The Global Alliance for Mental Health Advocates (GAMHA). J Ment Health Soc Behav 6(2):192.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Over the years there has been significant improvement in the survival rate of young people with cancer. This can be attributed to the development and progress in diagnoses, treatment and supportive care. Survivorship does come with a multitude of challenges and late effects; from the physical to the psychological, neuro-cognitive and psycho-social. This calls for a systematic, organized and compassionate approach in handling young people with cancer. Explanation and awareness from the time of diagnosis, proper understanding and engagement with patients and their families must be inculcated as well as the regular, open conversations at all levels. Anticipating the potential issues and complications will be helpful in planning their care pathways.

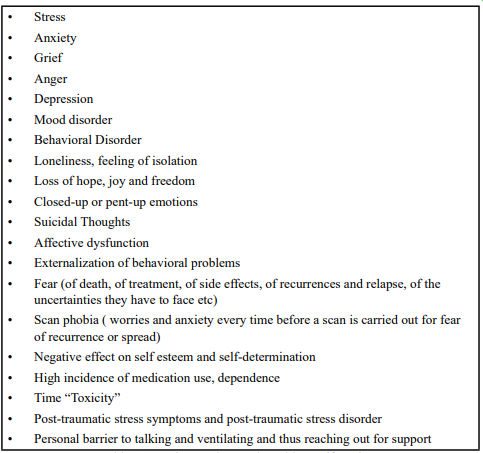

The psychological health aspects of the young cancer patient is critical and also a sensitive matter which need to be managed appropriately. Some unique considerations they may encounter include:

a. Uncertainty of their future with cancer

b. Thriving in society despite having cancer

c. Handling their confidence and self-esteem issues, as well as

d. Issues pertaining to body image, fertility and relationships

Fear of death and “death anxiety” are real concerns as well. At the stage where they are often flourishing and on an upward trajectory in their careers, it is definitely a drawback when cancer hits.

The learning and sharing of coping skills, keeping a positive attitude and mindset and staying strong throughout the whole journey is challenging enough, and yet these do not end when the treatment is completed. The longer term concerns and follow up can sufficiently cause much anxiety, worries and psychological impact, with concerns such as cancer recurrence phobia or scan-phobia. Thus, planning a young patient’s cancer care pathway is important. This must include psychological support, which can be stratified according to each individual psychological needs support; ie low, medium or high.

This is an awareness and information paper by some members of GAMHA. The Global Alliance for Mental Health Advocates (GAMHA) is a special global project initiated by Silver Ribbon (Singapore) and Lundbeck, with a vision to make Mental Health a global priority. With representation from some 21 countries, across the globe, GAMHA would like to express our support for an integrated care pathway for each young cancer patient, which must include the customized psychological needs assessment and support for as long as they need it.

Key words: Cancer, Young People, Psychological Wellness, Coping Mechanisms

Introduction

Childhood, adolescence and youth are the years where rapid changes and growth happens in a person’s life: physically, emotionally, cognitively as well as socially. Over and above the usual ups and downs, throw in the diagnosis of cancer; and the disruption, challenges and psychological distress will certainly increase. Cancer will affect every aspect of their young lives. According to World Health Organization, adolescents are those from 10 to 19 years and youth are those aged between 15 to 24 years. “Young people” thus refers to the wide age range of 10 to 24 years [1,2].

The frequency of children, adolescent and youth cancer continue to increase. The causes may be linked to genetic, inherited or environmental risk factors. The increasing trends is seen in almost all countries and across both genders; the commoner ones being leukemia, brain tumours and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [1-5]. Unlike adult cancer patients, these young people inflicted by the disease face a variety of unique challenges. In some cases, when diagnosis and treatment is delayed, fatality rate can be very high. With time, progress and developments in cancer drugs, technology and therapy, more options are now available, which has improved survival rates. This also means these young cancer patients are living and surviving longer. The positive part of this is if they are cured or remain in remission. However, living longer may also mean more concerns on relapse and complications; which may be linked to greater psychological distress and low health-related quality of life [1,3-5]. (Table 1)

Upon the diagnosis of cancer, there will be numerous changes, some of which could be life-changing, which the young person and their family will have to go through. Their developmental milestones will definitely be altered and affected. This is also dependent on the age at which the diagnosis is made. For children, decisions will be made by their parents and families. Those who are slightly older will probably recall the multiple hospitalizations, the investigations, scans and injections they have to go through, the loss of their play time with friends and some of the side effects (fatigue, loss of weight and appetite, low mood, loss of hair, nausea, vomiting etc) they experienced [3,6]. For the older child and adolescent, they may have a better understanding of the concept of illness, disease and cancer. Parents will play a critical role in the explanation and conversations with them. There will be loss of school days, having to later catch up with lessons. They may also recall how they were not allowed to socialise and play with their friends too freely, compared to their peers. For the youth inflicted with cancer, some may be pursuing higher education or working and thus the illness may be seen as a disruption to their life plans and career trajectory [7,8]. It will affect their social networks as well as personal relationships. Importantly, the psychological distress may not just be during the acute phase of the cancer, but may dwindle on for many years after completion of treatment [6,7,9] (Table 1).

They may go through the Kubler-Ross’s stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and finally acceptance; not necessarily in this order. Questions such as “Why Me?”, “Why at this young age?” and “What is going to happen to my education and career?”, “Isn’t cancer a disease of the old?” are common [10].

Coping Skills and Support Systems

Coping refers to the spectrum of thoughts and behavior that an individual or group can mobilize to manage a challenging, stressful or difficult situations. These situations may be internal or external; just as the coping skills itself can also be internal and external. Internal coping skills are within one’s self and involve the thoughts, self-determination and behavior each individual go through and demonstrate. Examples of internal coping include positive self-talk, managing your own mindset, deep breathing exercises, positive visualizations and meditation. External coping skills utilize things or individuals outside of oneself and the examples would include watching television, talking to friends, working out, reading, writing or journaling, attending counselling sessions and many others. Coping can also be looked at in terms of physical coping as well as psychological coping [11-13].

For the young cancer patients with their unique psychological needs, they may turn towards these coping mechanisms to help them handle issues such as:

e Uncertainty of their future with cancer

f Thriving in society despite having cancer

g Handling their confidence and self esteem issues as well as

h Issues pertaining to body image, fertility and relationships

The bottom line is that their mental health and wellness is key. Having a reasonable spectrum of support system and resources is beneficial and can go a long way for the young cancer patient (Table 2).

Uncertainty of their Future/ Thriving in Society

This is where many have fear that their lifespan will be shortened and they will not be able to fulfill all their wishes, aspirations and dreams. This may arise because of the dramatization of cancer patients over television dramas, movies and even on social media sharing platforms by cancer patients and their next of kin. They worry that their plans and life as well as career trajectories cannot be achieved. They may experience functional limitations and fatigue. Even if they do survive, they are often concerned that they may not be like “others”; their stamina may be lowered, their health may take a toll on their physical growth and development and mental capabilities, they may miss classes and work which could affect their chances of progress and promotion. They will encounter bullying and discrimination as a result of the lack of awareness and understanding of cancer by their peers, teachers, family members and colleagues as well as the lack of social and community support and understanding. All these are real concerns. Some may even stop planning their life and decide to live day-by-day. They feel they are left behind. In a competitive society, these considerations can be common, when young people cannot perform like their peers or even worse become discriminated. They feel disappointed and upset with themselves, their families and even the world around them. For the very young ones, parents and family members play a crucial role; with the need for frequent check-ins, heart-to-heart conversations, managing mindsets and providing explanation. For those who turn towards religion and spirituality, these may provide another platform for them to reconcile and come to terms. The journey can be like a roller-coaster, with its ups and downs, unpredictability and unique challenges [13-16].

Handling Confidence and Self esteem Issues

It may not be easy for a young person, whose life experience is still limited, to face the ‘mountain’ of challenges the diagnosis of cancer can bring on. They may encounter multiple perceived barriers at home, in school, in communities or at work. Thus, the presence and use of supporting resources to cope and manage their lives is very important. They can build confidence if they understand the trajectory of their cancer. Therefore, open and honest conversations with their healthcare team, oncologist, parents and other staff, and counselors is important. They may tend to mature faster than their peers sometimes. This would mean having to support them psychologically and emotionally, to adapt to the changes they will face. They may also need counselling and support if they feel they are “missing out” on some life experiences as compared to their peers and friends. Instilling hope, positivity and understanding can help them improve their self confidence and esteem levels. They must be made to realize that is no fault of theirs that they are inflicted with cancer. Peer mentoring programmes, where survivors are paired with young cancer patients, can offer valuable support, increase understanding and acceptance as well as help reconnect them with their friends in meaningful ways. These peers with lived experience represent an important resource group, often overlooked. The use of online peer to peer support support conversations can provide an opportunity to meet and greet virtually just to keep in touch and catch up with the young patients.

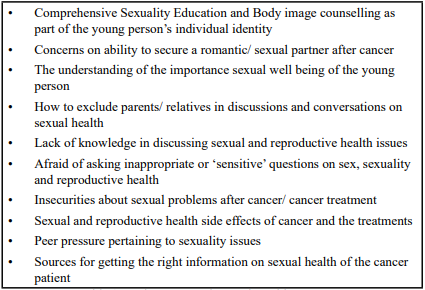

Body Image, Fertility and Relationships

With such a wide spectrum of paediatric, childhood and youth cancers today, as well as an expansion of the types of treatment and therapy available, the impact and effect on each individual young cancer patient can be very unique. They are at a stage of their life and development where peer pressure is a real issue, where appearances and being with the ‘in-crowd’ at school and society is top priority, and where, trying out the latest in fashion and trends make a very big difference. Therefore, if surgery is required, or chemotherapy causes hair loss, radiation causes pigmentation and discoloration, the emotional impact can cut very deep and some may not be able to handle. This is where open discussions and truthful sharing from the beginning must be done properly and adequately. Counselling may be required. For the older youth, joint and collaborative decision making can be done. Options should be discussed and their questions answered, in order to build trust. Significant effort may be required in allaying their anxieties related to body image. For the older youth in relationships, this need to be handled in a sensitive manner. Partners may worry that they may not live long enough to see marriage. They may worry about recurrences and relapses or even if there are genetic predisposition whereby they may pass the gene to their children, in some cases of cancer. Others may decide to refrain from being in a relationship or from marriage and having children. In specific cancers where fertility and reproductive capacity may be affected, desire to have children will have to be managed through counseling and open discussions with specialists (Table 3).

Besides just managing and handling the cancer patients, educating their family members, relatives, peers, and colleagues can also be very important, to help inculcate understanding and correct misperceptions/misconceptions. This can be a very crucial step in helping to allay anxieties amongst the people that the cancer patient or cancer survivor interacts with.

Coping Skills: Changing Mindset, Unlearning and Re-Learning

In building up their own coping skills and capabilities, they will need to reflect and think about issues or topics of concern to them. These could be topics they think about very often or find that they are unable to resolve these concerns. They may seem to mature faster than their peers in some cases because of this. Once they have overcome the initial emotional challenges, they may need to put things and their life in perspective and take stock of issues [7,11,17]. They may have to unlearn old approaches, outlook and mindset and relearn new strategies. These young people can learn to:

a. Have a positive outlook, learn to convert negative thinking to positive thinking. Practice a lot of positive self-talk which can build up their confidence levels. They can learn to use “replacement thoughts” ie. converting negative thoughts to positive ones

b. Practice positive thinking and the use of imagery, just like it is practiced amongst elite athletes. The subconscious mind cannot differentiate real experience and imagined experiences so thinking about and having imageries can be very useful as well.

c. Use stress relieving and relaxation techniques. These can be very personal to each individual. Examples may include, aromatherapy, yoga, massage therapy, deep breathing exercises and meditation.

d. Create a ‘gratefulness’ diary: charting what one is grateful for everyday

e. Use of positive quotes and posters to be placed around the room, or on the desk, to serve as reminders and visual cues.

f. Make a list of accomplishments every day. Even simple things such as “ I manage to overcome my pain today with less pain killers” can be an achievement.

g. Have their own list of coping skills e.g. writing or journalling, running, watching television, listening to music or doing volunteer work, and spiritual enlightenment

Cross Cultural Variations and Understanding

There are many differing beliefs and perceptions about cancer across various ethnic groups. There are also differences across the western versus the eastern or Asian population. The former can be more vocal, open and confident in sharing their views, emotions and queries openly, whereas the latter tend to be more private, conservative and less vocal in sharing. They would only share with their closest family members of friends. In eastern societies, options such as traditional treatment, use of herbal concoctions and supplements and TCM (Traditional Chinese Medication), including use of oils, massage and acupuncture are also being used in the treatment of cancer. Some of these may not be evidence-based from the scientific perspective, but may seem to have a proven “track record” within that specific community. For an older young person affected by cancer, they may become subjected to more stress and anxieties if their older family members wish to subscribe to such therapy, which they themselves are not receptive too. This can add another layer of psychological burden and mental stress. Conflicts can then arise within the family, which affects their mental wellness. Such conflicts are discomforting as the young cancer patients may not want to go against their parents/ senior family members’ wishes as they realize that they need these people to help them in care giving, physical support and as their emotional resource. Some of these factors may have either a direct or indirect impact on the mental health of the young cancer patients. These inter-generational differences in beliefs may need to be handled amicably to avoid negative outcomes in the family dynamics and interactions [18-20].

Different ethnic groups may also turn towards specific religion and religious practices to help them get through this challenging period in their lives [21].

Death Anxiety

Death is often a taboo topic across many cultures, which can generate heightened emotions. In many cases and contexts, it remains an unspoken topic. It is a phenomenon of great change for the family and loved ones. Many wonder if death will hurt or be painful. This is especially with cancer patients who may have to go through a variety of procedures, endure pain for a variety of reasons throughout the course of their illness. Often young people will not think of death, but when diagnosed with cancer, this becomes a thought which may bring on worries, anxiety and even fear. Others may go through a denial period and may not want to discuss or talk about it. For those with certain religious practices, they will be guided by their beliefs. Once a level of acceptance is reached, some degree of planning and preparation for death is not uncommon. Some may reach a stage where they are even willing to talk openly about their wishes at the end of the life, what they want to fulfill before death and what they hope for after their death. Some may have a “to do” list to attain, whilst others may just focus on what they feel is most important and meaningful to them. Younger patients and children may not have to be concerned about leaving a will but the older, working youth may have to consider this [21,22].

Fear of death upon the diagnosis of cancer can also manifest in many ways, such as, being hypersensitive about each and every symptoms, including some minor ones. Some may experience somatization with a spectrum of multiple complaints, that it becomes challenging to differentiate these from real, organic symptoms they may encounter.

In view that the experience towards death for each cancer patient is unique, people around them should support them in a customized fashion as deemed relevant and appropriate. Deep psychological support, religious and spiritual counselling may be useful [21,23].

Spirituality

Experiencing spiritual distress is not uncommon among cancer patients. Unfulfilled spiritual needs could be a contributor causing distress. Spiritual distress and suffering may influence a person's experiences and symptoms associated with illness and contribute to poor health and psychosocial outcomes. It is believed that spirituality is one essential factor providing a context for cancer patients to derive hope and meaning to cope with their illness from the time of diagnosis through treatment, survival, recurrence, and dying, and it could serve as a protector factor, buffer the deteriorating impacts of life stresses and illness [2,5]. Individuals who are living with a life-threatening illness such as cancer may be most vulnerable to spiritual distress and are more aware and sensitive to their spiritual selves and spiritual needs.

Cancer patients reported that spirituality is a source of strength that helps them cope with their cancer experiences, define wellness during treatment and survivorship, find meaning in their lives, find a sense of health, and make sense of their cancer experiences during illness [2,5,6].

Nurses and other health-care professionals have responsibilities to assess cancer patients’ spiritual needs as well as to plan and deliver culturally appropriate spiritual care to them. More studies investigating spiritual well-being, spiritual needs, and culturally appropriate spiritual care for cancer patients with Asian cultural backgrounds are urgently needed to overcome barriers preventing the delivery of proper and competent spiritual care to all cancer patients.

It is necessary to ensure caregivers and health-care professionals become familiarized with the aspects of spirituality, understand cultural influences on cancer patients’ spirituality and spiritual well-being, and overcome the barriers to providing spiritual care to properly deliver appropriate and comprehensive care to each cancer patient.

Psychological Wellness and Support Services

Across the spectrum of young persons with cancer, the level of psychological support required may vary and this is also dependent on many factors; individual factors and characteristics, family factors, presence of resources and how these are utilized etc. For those with low psychological support needs, these can often be fulfilled by people who are around the patient such as their counsellor, friends and family members, who need not have specialized training in mental health. Patients in this group may need less intensive psychological follow up and it may be more ad hoc or on a “as needed” basis. Patients who are in the medium psychological support needs group, require more follow up and often they will also need healthcare professionals with specific mental health training. The final group with high psychological support needs, will need trained mental health personnel very early after the diagnosis is made and often throughout their journey with cancer. Their situation is more complex and may be integrated with a multitude of factors, which need to be resolved and ironed out. Their follow up is also more frequent [24-26].

Today, many young cancer survivors do well after treatment, but there is still a significant proportion of them who experience psychological distress, poor quality of life compared to what they had before and post-traumatic stress symptoms. In fact the latter is reported with a current prevalence of between 2-20% , with a lifetime prevalence of up to 21% to 35% [27,28]. In view of this spectrum, it may become necessary to ensure referral to psychological wellness counselling and support services is included in the care pathways of all young cancer patients. They should be provided with stratified level of services based on their level of psychological support needs. Currently, it is more reactive and ad hoc, where the referral is made only when manifestations of some form of psychological need arises. A dedicated service and trained personnel, counsellors and staff will be very useful. The outcomes and psychological impact will bear fruits in the medium to longer term. These personnel should be trained in handling children and young people, understand their issues and be able to manage the family dynamics and concerns. Unique issues such as peer pressure, fitting with the ‘in crowd’ at school or at work, the youth trends and the mindset of each young person is crucial to understand. The building of trust is also important. These personnel should be able to have open, honest, and adaptable conversations with the young cancer survivors. Even if they are in remission, follow up is still to be encouraged, although it can be less frequent. The idea is not to be too prescriptive but allow flexibility and personal customization.

The service should have integration of social service, counselling, financial support, psychological support, genetic counselling and other advisory services as deemed necessary. Not every young cancer patient will need all services but they can be customized appropriately. For the cancer patient still in school, working with their school counsellor will be helpful and for those who are older and need assistance with job placement, the relevant training and support can be given. Combining all these services and guiding the patient on their journey as they battle cancer and beyond will certainly have beneficial medium to longer term impact. This will make them feel cared for, appreciated as members of a community or society and will see them through challenging times. Using mindfulness and creative approaches as well as trying out new techniques to help maintain balance and positivity amongst the young cancer patients can be meaningful for them. They may feel more gratefulness and a greater appreciation for life.

Many of the parents of young cancer patients are also in need of psychological support and counselling. Their psychological distress and fear may extend beyond the treatment period into the years of their children’s survival. Thus, this support must not be left out of the care pathway plans [29,30].

The counselling and follow up can be done one-on-one or in a group. Face to face sessions are useful but offering of virtual sessions and e-consultations provide more options as well. Some young cancer patients may prefer to meet counsellors on their own, whereas others may choose to have their family with them. For married cancer patients, spouses presence is also helpful. The spectrum and range of topics to be covered can be wide, including addressing psychological safety, stress management, coping mechanisms, early efficacy, acceptability, social skills and competence, psycho-education, relaxation techniques, positive thinking and many others [31].

Neuro-Cognitive Dysfunction

Neuro-cognitive deficits have been observed amongst childhood cancer survivors. In some series it has been reported up to 35%.Those with central nervous system tumours are at highest risk, in view of the higher dose of cranial radiation therapy and greater brain volume affected. The spectrum of presentation can be wide, from mild to moderate and even severe in some cases. These presentation may include decrease in general intelligence, impairment of processing skills and speed, impaired verbal fluency and cognitive flexibility as well as impact on memory and attention [32-35].

Therefore, in the approach to supporting young cancer patients, these will have to be taken into account. Before their therapy, all the risks and potential effects should be shared with them. They can then plan and manage their expectation, if they are in the older age range of ‘young patients’. In other cases the parents and family should be appraised of this. For those who are already manifesting these neuro-cognitive effects, a tremendous amount of patience and understanding in approaching them. Counselling and therapy should be customized as required. Often when they realize their dysfunction and deficit, this may lead to isolation, depression, sadness and other behavioral manifestations. Others who have learnt to accept this, may have to manage their lifestyle and work commitments. For example, if they do realize their reaction time may not be as quick, they may not want to continue to be in certain jobs or they may choose jobs that may not portray this dysfunction so vividly. All these may not be easy for the young person to accept, in the prime of their lives. Thus, the support, love and understanding of people around them is most crucial for their healing, growth and development [32,33,35,36].

With-Holding The Diagnosis of Cancer

When the diagnosis is “cancer”, there will be much emotions and anxiety involved, whether it is in adult or young people. For the very young, who may not have much understanding of the issues and terminology, parents will front the journey and management decisions. These young children may only have an understanding of the concept of being “sick” and having to visit the hospital or see a doctor. They may understand the fact that they need to take medications or have injections ( which may come with a negative experience and memory), because they are ‘unwell’. They may understand this also form the perspective tat they are not like their other friends.

For young people, when the diagnosis of cancer is made, two possibilities may surface:

a For the older and working young, they may at first keep the diagnosis to themselves. They may have to weigh the pros and cons of sharing the information with their family (perhaps with aged parents) and spouses/ children. It may soon become obvious to the people around them that they are unwell and discussions or questions will surface, where the patient will have to open up and share the facts.

b When the diagnosis is made amongst some young people, it may first be broached to their parents, who may then request the doctors/ healthcare staff to not reveal the diagnosis to the patient. Again, the patient will need some explanation as to why they are in hospital frequently and need treatment which may make them experience side effects.

Either way, it is not easy to keep the diagnosis and eventually, at some appropriate time, the discussion will have to take place. From the medical perspective, doctors respect the autonomy patients have in knowing and understanding their disease and it can be challenging to ask the doctor to “hide” or not mention the diagnosis, especially f the patient were to ask them directly. Families keeping quiet and discussing behind the patients’ back may also bring on suspicion on the part of the patient, who will start asking questions for clarifications. The families good intention of not wanting to share the diagnosis may backfire and cause more distress on everyone’s part.

Culture has a strong impact on this issue of sharing the diagnosis. There are also differences in the way this is handled, both in the western and eastern cultures. Eventually, it is probably best to be open about the diagnosis and garner family support. In fact family bonds and relationships often can be strengthened during these periods of ‘hardship’ in a young person’s journey with cancer.

A Checklist Approach for the Young Cancer Patient

The following list may be used as a guide that the young cancer patient can cross check and make reference to during their journey with cancer.

1. Internalize the diagnosis and treatment options as discussed with the oncologist. Take time to ask for clarifications as needed.

2. Manage your mindset and be prepared to embrace change that will take place from the point of diagnosis onwards. Managing mindset is a critical step to help you navigate the physical and psychological shifts you will encounter. Be flexible as you move through the different stages of treatment and recovery.

3. Be prepared to slow down from your usual pace as needed.

4. Request for as many open conversations and consultations as needed to help assimilation of information related to cancer

5. Research and read if possible, from reliable sources, which can be requested for from your oncologist. Social media may not always have the most accurate information, thus the need to verify these.

6. Have as many combined or separate individual discussions with your family members, spouse and siblings as needed. There should be heart-to-heart sharing, with frank concerns addressed and clarified. Even the simplest things may need to be addressed eg. who will be taking or driving you for your treatment, who will be your care-giver, who will take time off work on a rotational basis during your chemotherapy period or who will cook for you.

7. Perform reflection as much as you need to. This is where you can focus and consolidate your thoughts, emotions and plans, moving forwards.

8. Make a personalized list for yourself: the do’s and don’t’s, the positive and negative, the “to do” and “to avoid”, list of questions and concerns to clarify. This can help you keep track of what is important to you.

9. Make a plan for yourself on how to manage your life: ie school, education, work-life balance, promotions and taking on new roles, time-off for treatment, family time, socialization or voluntary work commitments. Plan for a well-balanced life.

10. Seek spiritual guidance. Talk to your religious leader if you feel it is necessary, for advice.

11. Find a truly “trusted person” you can talk openly to and approach for any matter, including the most intimate and private concerns. Having such a person can make a lot of difference to a young cancer patient, facing new experiences and challenges.

12. Maintain your psychological well being: practice breathing exercises as appropriate, ensure enough rest, sleep, proper diet, plan your social activities time and hobbies that you may continue to pursue. A balance need to be struck in order to continue with your life. If some things need to be deferred or delayed, you will need to give these weighted consideration, bearing in mind your health and cancer status.

13. Keep yourself positive and happy as much as possible. Make your “bucket” list:

• Things to do

• Activities to pursue

• Countries to visit

• Food you desire to eat or try, etc

14. Find strength in your own personalized ways. Understand that the journey is yours and you can direct it to a certain extent. You can take charge, just as reflected in this quote “If the egg breaks from outside, life ends. If the egg breaks from inside, life begins. Great things begin from ‘inside of you’ (from within)”

15. Finally, train yourself to look for ‘the ordinary miracle’ everyday

Conclusion

Planning a young patient’s cancer care pathway is important. This must include psychological support, which can be stratified according to each individual psychological needs support; ie low, medium or high.

This is an awareness and information paper by some members of GAMHA. The Global Alliance for Mental Health Advocates (GAMHA) is a special global project initiated by Silver Ribbon (Singapore) and Lundbeck, with a vision to make MH a global priority. With representation from some 21 countries, across the globe, GAMHA would like to express our support for an integrated care pathway for each young cancer patient, which must include the customized psychological needs assessment and support for as long as they need it.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E. et al. (2022). Cancer statistics, CA Cancer J Clin; 72: 7-33 View

The WHO definition of Young People. Adolescent and young adult health (who.int) ( accessed on 26 Sept 2024) View

Huang, J., Chan, S. C., Ngai, C. H., et al. (2023). Global incidence, mortality and temporal trends of cancer in children. A joint point regression analysis. Cancer Med; 12: 1903-1911 View

Health Promotion Board Singapore. 50 years of cancer registration in Singapore cancer registry 50th Anniversary Monograph 1968-2017.View

Butler, E., Ludwig, K., Pacenta, H. L., et al. (2021). Recent progress in he treatment of cancer in children. CA Cancer J Clin; 71(4): 315-332View

Mullen, C. J. R., Barr, R. D., Franco, E. L., (2021). Timeline of diagnosis and treatment: The challenge of childhood cancer. Br J Cancer; 125: 1612-1620View

Fong, F. J. Y., Wong, B. W. Z., Ong, J. S. P., et al. (2024). Mental wellness and health related quality of life of young adult survivors of childhood cancer in Singapore.

Michel, G., Vetsch, J., (2015). Screening for psychological late effects in childhood, adolescence and young adults cancer survivors: A systematic review. Curr Opin Oncol; 27: 279-305 View

Larsen, P. A., Amidi, A., Ghith, N., et al. (2023). Quality of life of adolescents and adult survivors of childhood cancer in Europe: A systematic review. Int J Cancer; 153: 1350-1375 View

Tyrell, P., Harberger, S., School, C., et al. (2024). Kubler Ross Stages of dying and subsequent models of grief in StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing In: Available at View

Wenniger, K., Helmes, A., Bergel, J., et al. (2013). Coping in long term survivors of childhood cancer in relation to psychological distress. Psycho-Oncology; 22: 854-861 View

Hildenbrand, A. K., Alderfer, M. A., Deatrick, J. A., et al. (2014). A mixed methods assessment of coping with pediatric cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 32(1):37-58. View

Friend, A. J., Feltbower, R. G., Hughes, E. J., et al. (2018). Mental health of long term survivors of childhood and young adult cancer: A systematic review. Int J Cancer; 43: 1279-1286 View

Fidler, M. M., Ziff, O. J., Wang, S., et al. (2015). Aspects of mental health dysfunction amongst survivors of childhood cancer. Br J Cancer; 113: 1121-1132 View

Schuelke, T., Crawford, C., Kentor, R., et al. (2021). Grief support in paediatric palliative care. Children; 8: 278 View

Hughes, L., taylor, R. M., beckett, A. E., et al. (2024). The emotional impact of a cancer diagnosis: a qualitative study of adolescent and young adult Experience. Cancers; 16: 1332 View

Osborn, M., Johnson, R., Thompson, K., et al. (2019). Models of care for adolescents and young adults cancer program. Paediatric Blood Cancer; 66: e27991 View

Lam, C. S., Peng, L. W., Yang, L. S., et al. (2022). Examining patterns of traditional Chinese medicine use in pediatric oncology: A systematic review, meta-analysis and data-mining study. J Integr Med. Sep;20(5):402-415. View

Hongxin, J., Lina, Bu., (2024). Progress in the treatment of lung adenocarcinoma by integrated traditional Chinese and Western medicine, Frontiers in Medicine; 10.3389/fmed.2023.1323344,10 View

Zhoudi, L., Yiwei, S., Lianli, Ni., et al, (2024). Study on the Mechanism of Yadanzi Oil in Treating Lung Cancer Based on Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking Technology, ACS Omega; 10.1021/acsomega.3c10105, 9, 17, (19117-19126) View

Çaksen, Hüseyin., (2021). Religious Coping in Parents of Children With Cancer. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/ Oncology; 43(6): 241-242 View

Blasco, T., Jovell, E., Mirapeix, R., et al. (2022). Patients desire for psychological support when receiving a cancer diagnosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health; 19: 14474 View

Fardell, J. E., Irwin, C. M., Vardy, J. L., et al. (2023). Anxiety, depression, and concentration in cancer survivors: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey results. Support Care Cancer. 15;31(5):272. View

Lange, M., Licaj, I., Clarisse, B., Humbert, X., Grellard, J. M., Tron, L., et al. (2019). Cognitive complaints in cancer survivors and expectations for support: results from a Web-based survey. Cancer Med. 8(5):2654–2663. View

Götze, H., Friedrich, M., Taubenheim, S., Dietz, A., Lordick, F., Mehnert, A., (2020). Depression and anxiety in long-term survivors 5 and 10 years after cancer diagnosis. Support Care Cancer. 28(1):211–220. View

Pitman, A., Suleman, S., Hyde, N., et al. (2018). Depression and anxiety in patients with cancer BMJ. 361, k1415 View

Mertens, A. C., Gillelard, M. J., (2015). Mental health status of adolescent cancer survivors. Clin Oncol Adolesc Young Adults; 5: 87-95 View

Taieb, O., Moro, M. R., Banbet, T., et al. (2003). Post-traumatic stress symptoms after childhood cancers. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry; 12(6): 255-264 View

Wakefield, C. E., McLoone, J. K., Butow, P., et al. (2011). Parental adjustment to the completion of their children’s cancer treatment. Pediatr Blood; 56(4): 524-531 View

Pai, A. L., Greenlay, R. N., Lewandowski, A., et al. (2007). A meta-analytic review of the influence of pediatric cancer on parents and family functioning. J fam Psychology; 21(3): 407-415 View

Niedzwiedz, C. L., Knifton, L., Robb, K.A., et al. (2019). Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: a growing clinical and research priority. BMC Cancer. 19:943View

Michel, G., brinkman, T. M., Wakefield, C. E., et al. (2020). Psychological outcomes, health-related quality of life and neurocognitive functioning in survivors of childhood cancer and their parents. Pediatr Clin N America; 6(7): 1103-1134 View

Ullrich, N. J., Embry, L., (2012). Neurocognitive dysfunction in survivors of childhood brain tumors. Semin Pediatr Neurol; 19(1): 35-42View

Knull, K. R., Hardy, K. K., Kahallay, L. S., et al. (2018). Neurocognitive outcomes and interventions in long term survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36(21): 2181- 2189View

Pulsifer, Mb, Duncanson, H., Grieco, J., et al. (2018). Cognitive and adaptive outcomes after proton radiation for pediatric patients with brain tumours. Int J radiat Oncol Biol Phys; 102(2): 391-398 View

Cheung ,Y. T., Krull, K. R., (2015). Neurocognitive dysfunction outcomes in long term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated on contemporary treatment protocols: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehavr Rev; 53: 208-220 View