Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour Volume 6 (2024), Article ID: JMHSB-193

https://doi.org/10.33790/jmhsb1100193Research Article

Imagining Failure: How Episodic Future Thinking Relates to Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms

Megan E. Morillas1*

1Department of Psychology, San Diego State University, California, United States.

2Professor, Department of Psychology, California State University, Fresno,United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Megan E. Morillas, Department of Psychology, San Diego State University, California, United States.

Received date: 04th October, 2024

Accepted date: 16th December, 2024

Published date: 18th December, 2024

Citation: Morillas, M. E., & Oswald, K. M., (2024). Imagining Failure: How Episodic Future Thinking Relates to Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms. J Ment Health Soc Behav 6(2):193.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Episodic Future Thinking (EFT) refers to the cognitive ability to mentally simulate specific and vivid autobiographical future events. While EFT serves several adaptive functions in healthy populations, a small, but growing body of literature has begun to probe impairments in EFT linked to psychopathology. The present research sought to examine whether these deficits extend from temporary (i.e., state anxiety) to lasting (i.e., trait anxiety, depression) forms of internalizing symptomatology, and how these impairments relate to perceived success and emotional valence when imagining novel future tasks. This relationship was examined across two studies, where participants envisioned detailed episodic scenarios for seven novel future tasks and subsequently rated each scenario on perceived task success and valence. Internalizing symptoms were assessed using the State- Trait Anxiety Inventory and Beck Depression Inventory. Findings revealed a significant negative relationship between perceived task success, state anxiety, and depression, consistent across both an initial investigation and replication. These results suggest that individuals with higher levels of internalizing symptoms may have a tendency to adopt a more negative outlook when envisioning themselves performing future tasks, potentially contributing to the maintenance and exacerbation of symptoms. These novel findings provide further support for differences in future-oriented cognitive patterns associated with anxiety and depression, as well as demonstrate a need for the development of targeted interventions aimed at modifying negative future thinking in affected populations.

Keywords: Anxiety, Depression, Episodic future thinking, Imagination

Introduction

Autonoetic consciousness, the ability to mentally perceive oneself in the past, present, and future [1], is a phenomenon that has garnered considerable attention over the last decade. One specific facet of this ability—episodic memory—involves the recollection of personally experienced past events [2], whereas the mental representation of future events is referred to as prospection [3]. Prospection serves as an umbrella term encompassing a wide range of futureoriented cognitive phenomena, including affective forecasting, autobiographical planning, episodic simulation, prospective memory, and temporal discounting [4]. The present study investigates one form of prospection—episodic future thinking (EFT)—which refers to the ability to project oneself forward in time to pre-experience a future scenario [5].

A breadth of literature highlights the diverse functions that EFT serves, ranging from planning [6] and spatial navigation [7] to decision-making [8, 9] and emotion regulation [10, 11]. Perhaps one of the most critical functions of EFT is the ability’s capacity to generate joy in daily life, with 12% of our daily thoughts occupied by future cognition [12]. Generally speaking, humans exhibit a natural tendency to imagine themselves achieving success in the future rather than experiencing failure, with the mere anticipation of these positive outcomes fostering a sense of happiness and fulfillment [13].

Although the advantages of EFT in healthy populations are welldocumented, a growing body of evidence suggests that the ability functions differently in individuals with a diagnosis or underlying symptoms of a psychological disorder. A meta-analysis conducted by Hallford et al. [14] analyzed 19 empirical studies illustrating significant associations between psychopathology and decreased EFT detail and specificity, with notable effects observed in depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Collectively, these findings suggest that individuals with such diagnoses exhibit impairments in imagining episodically rich futures, a deficit suspected to contribute to poorer mental health outcomes in these populations.

While a handful of studies have examined EFT in the context of depression and other mood disorders, far fewer have investigated its connection to anxiety. Given the high rates of comorbidity between anxiety and depression [15], further investigation within the context of both conditions is essential to better understand the role of this ability in internalizing disorders. Most research investigating futureoriented thought in anxiety and depression targets worry. While worry and EFT both involve thinking about possible future scenarios, the two phenomena differ largely in contextual and emotional properties. For instance, worry is defined as a negative, often uncontrollable chain of thoughts [16]. Meanwhile, EFT is characterized as a positive and constructive cognitive process for imagining meaningful and detailed future events.

Over the last few decades, a number of studies have investigated the relationship between anxiety, depression, and future cognition, forming the empirical and theoretical basis of subsequent literature. One critical finding involves the different frequencies at which anxious and depressed individuals generate positive and negative experiences. In comparison to asymptomatic populations, anxious individuals generate significantly more negative experiences [17], while depressed individuals generate significantly fewer positive experiences [18] when imagining personally-relevant future events.

Expanding on these foundational insights, recent literature has sought to further disentangle the link between internalizing symptomatology and EFT specifically. One such study conducted by Wu et al. [19] aimed to characterize EFT in individuals with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) using an experimental recombination paradigm—a procedure that combines different elements from a participant’s life to facilitate the imagination of personally plausible, yet novel, future scenarios. Results revealed that participants with GAD added less spontaneous detail to episodic future simulations. Participants also rated negative events as more plausible to occur in their personal future compared to their non-anxious counterparts. These findings reveal a negativity bias in EFT for individuals with GAD as well as a deficit in generating vivid simulations for such populations.

In an additional investigation, Hallford et al. [20] explored the relationship between phenomenological characteristics of EFT and anticipatory pleasure in individuals with a major depressive episode (MDE). Depressed and non-depressed participants provided descriptions of personally-relevant positive future events and then rated each event for phenomenological characteristics of EFT and anticipatory pleasure. Results indicated that participants with MDE simulated events with less detail and vividness, perceived events as less likely to occur, and associated each event with less state anticipatory pleasure.

Similar findings extend to less severe forms of psychological strain, such as life stress. Lalla and Sheldon [21] explored the relationship between perceived life stress, emotional valence, and the capacity to recall personal experiences and envision future events. Participants generated past and future events to various positive and negative cues and completed a questionnaire that measured life stress. Results indicated that when participants experienced higher levels of life stress, they evaluated past and future events with a lower positivity bias. Additionally, higher levels of stress were associated with tendencies to rate positive events as less likely to occur and to rate overall events with a more negative valence.

The present research aimed to further elucidate the relationship of EFT to both temporary and lasting forms of psychological strain, such as state anxiety, trait anxiety, and depressive symptoms. Our primary research questions were: Do individuals who experience state anxiety, trait anxiety, and characteristics of depression imagine themselves performing novel tasks less successfully, and do individuals who experience state anxiety, trait anxiety, and depressive symptoms view themselves performing novel future tasks with a more negative valence?

Prior research exploring EFT and psychological disorders consistently demonstrates a wide array of deficits in both temporary and lasting forms of psychological strain. Drawing from previous findings of EFT deficits in stress [21], anxiety [19], and depression [20], we predicted that individuals experiencing state anxiety, trait anxiety, and depressive symptoms would imagine performing novel tasks less successfully than those who experience fewer symptoms. Additionally, given findings on negative future outlook styles within anxious and depressed individuals [17, 18], we also predicted that individuals experiencing state anxiety, trait anxiety, and depressive symptoms would simulate future events with a more negative valence compared to those with lower levels of symptoms.

Study 1

Past research highlights the relationship of temporary forms of psychological strain such as day-to-day life stress with impaired EFT [21]. Given this finding, we explored the relationship between other forms of temporary psychological strain and the way one envisions performing future tasks. Here, we investigated the relationship between novel future task imagination, state anxiety, and symptoms of depression. Our hypotheses were: 1.) Individuals experiencing higher state anxiety and more depressive symptoms would simulate novel future events with a more negative valence than those with lower levels of symptoms, and 2.) Individuals experiencing higher state anxiety and more depressive symptoms would imagine performing novel future tasks less successfully than those with fewer symptoms. Participants generated scenarios of themselves performing seven novel future tasks. Following each simulation, participants detailed perceived task performance and valence (i.e., negative, neutral, or positive) for each imagined scenario. Then, participants completed the Beck Depression Inventory and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory- State Anxiety Scale.

Method

Participants

One hundred and twelve undergraduates at California State University, Fresno, were recruited using the Department of Psychology experimental participation system. Nineteen participants failed to complete the surveys and were therefore excluded from all analyses. Thus, the final sample consisted of 93 participants. Sixtynine percent of participants were women, with ages ranging from 18 to 22 (M = 19.19, SD = 1.05). Fifty-four percent of participants identified as Hispanic or Latino, 25% identified as Asian or Pacific Islander, 16% identified as Caucasian, 3% identified as other, and 2% identified as Black or African American. All participants earned a high-school degree or equivalent. Participants were told they were participating in a study that sought to better understand how humans think about future events. Each student received one credit towards their Introduction to Psychology research requirement for the completion of the 20-minute online survey.

Materials

Seven novel EFT cues (see Appendix A) were developed and piloted by the researchers in order to evaluate EFT. Task novelty and imagination ease of the EFT cues were screened in a previous survey (n = 25) to ensure the cues conformed to three parameters: undergraduates have not performed the activity, and one can easily imagine themselves performing the task both successfully and poorly (see Appendix A for ease of imagination parameters).

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was used to assess depressive symptoms. The BDI is a widely used 21-item self-report questionnaire that evaluates the severity of depression [26]. This selfreport instrument has exhibited high internal consistency (α = .91) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.93 [23]).

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-State Anxiety Scale (STAI-S Anxiety Scale) was used to measure anxiety. The STAI-S Anxiety Scale is a widely used 20-item self-report inventory evaluating “state” anxiety [24]. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (e.g., from “Not at all” to “Very much so”). This self-report instrument has exhibited high internal consistency (α = .86–.95) and test-retest reliability (r = .65–.75 [24]).

Design and Procedure

In an online survey using Qualtrics, participants were displayed seven cues and asked to generate scenarios performing novel tasks (e.g., “Take a moment to vividly imagine yourself directing traffic in a busy intersection”) (see Appendix A). After imagining each scenario, participants detailed their imagined physical exertion, emotional state, environment, and surroundings through a written description. Participants were then asked to rate perceived task success on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “very unsuccessful” to “very successful” and simulation valence (i.e., positive, neutral, or negative) (see Appendix B). After participants imagined, detailed, and rated all seven events, the Beck Depression Inventory and the STAI-S Anxiety Scale were administered to measure state anxiety and depressive symptoms. Last, demographics were assessed through a brief questionnaire to assess gender, age, ethnicity/race, education level, and occupational status.

Results and Discussion

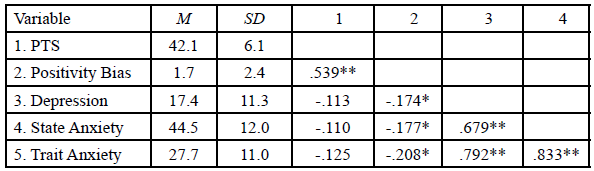

To measure the perceived success of the imagined events, a “perceived task success” score was computed for each participant by totaling the seven task success scores. A “positivity bias” score was also computed by calculating the frequency counts of events simulated in a positive, neutral, or negative valence. Negative valence frequencies were subtracted from positive valence frequencies to create an overall positivity bias score for each participant. BDI and STAI-S results were scored per standard scoring instruments to represent depressive symptom and state anxiety scores.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were computed to evaluate the relationship between depressive symptoms and perceived task success, as well as positivity bias. There was a negative correlation between depressive symptomatology and perceived task success, r(91) = -0.22, p < .05. Additionally, there was a negative correlation between depressive symptoms and positivity bias, r(91) = -0.26, p < .05.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were also computed to assess the relationship between state anxiety and perceived task success, as well as positivity bias. There was a negative correlation between state anxiety and perceived task success, r(91) = -0.31, p < .01. Additionally, there was a negative correlation between state anxiety and positivity bias, r(91) = -0.49, p < .001.

The current study was motivated to explore the relationship between internalizing symptoms, positivity bias, and perceived task performance in episodic future thinking. We first hypothesized that individuals with higher levels of state anxiety and more symptoms of depression would simulate future events with a more negative valence than those with lower levels of symptoms. Second, we hypothesized that individuals with higher state anxiety and more symptoms of depression would imagine performing novel tasks less successfully than those with fewer symptoms. Findings demonstrated that individuals with higher scores of state anxiety and depressive symptoms viewed imagined events with a lower positivity bias, as well as imagined performing tasks less successfully. Thus, both hypotheses of the current study were supported.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Coefficients for Study Variables

Note. ** p < 0.01 (2-tailed); * p < 0.05; N = 93; PTS - Perceived Task Success

Study 2

Study One demonstrated that individuals who experience temporary forms of psychological strain are more likely to imagine themselves completing novel future tasks less successfully and with a more negative valence. The aims of the current study were twofold: 1.) to replicate the findings of Study One, and 2.) to explore if this relationship extends to more lasting forms of psychological strain (i.e., trait anxiety). We first hypothesized that individuals who experience higher levels of trait anxiety, state anxiety, and depressive symptoms would imagine performing novel tasks less successfully. Second, we hypothesized that individuals who experience higher levels of trait anxiety, state anxiety, and depressive symptoms would imagine performing novel tasks with a more negative valence.

Method

Participants

One hundred and fifty-four undergraduate students at California State University, Fresno were recruited using the Department of Psychology experimental participation system. Twenty-eight participants failed to complete the survey and were therefore excluded from all analyses. Thus, the final sample consisted of 126 participants. Seventy-five percent of subjects were women, with ages ranging from 17 to 23 (M = 19.35, SD = 1.87). Fifty-eight percent of participants identified as Hispanic or Latino, 19% identified as Asian or Pacific Islander, 15% identified as Caucasian, 6% identified as Black or African American, 2% identified as other, and 1% identified as Native American or American Indian. All participants earned a high-school degree or equivalent. Participants were told they were participating in a study that sought to better understand how humans think about future events. Each student received one credit towards their Introduction to Psychology research requirement for the completion of the 20-minute online survey.

Materials and Procedure

Materials and procedures were identical to Study One with the following exception: The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) was used to measure both state and trait anxiety, replacing the STAI-S (which only measured state anxiety) in Study One. The STAI is a widely used 40-item self-report inventory, with 20 items evaluating “state” anxiety (STAI-S Scale) and 20 evaluating “trait” anxiety (STAI-T Scale) [24]. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (e.g., from “Not at all” to “Very much so”). This self-report instrument has high internal consistency (α = .86–.95) and test-retest reliability (r = .65–.75 [24]). A brief demographics questionnaire was used to assess participants’ gender, age, ethnicity/race, education level, and occupational status.

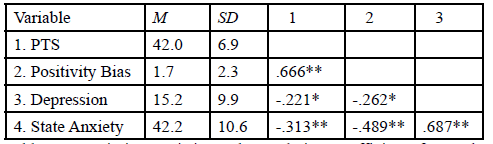

Results and Discussion

As in Study One, to measure the perceived success of the imagined events, a “perceived task success” score was computed for each participant by totaling the seven task success scores. A “positivity bias” score was computed by calculating the frequency counts of events simulated in a positive, neutral, or negative valence for each participant. Negative valence frequencies were subtracted from positive valence frequencies to create an overall positivity bias score. BDI and STAI-S results were scored per standard scoring instruments to represent depressive symptom and state anxiety scores.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were computed to evaluate the relationship between depressive symptoms and perceived task success, as well as positivity bias. There was a negative correlation between depressive symptomatology and positivity bias, r(124) = -0.17, p < .05. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were also computed to assess the relationship between state anxiety and perceived task success, as well as positivity bias. There was a negative correlation between state anxiety and positivity bias, r(124) = -0.18, p < .05. Lastly, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were computed to assess the relationship between trait anxiety, perceived task success, and positivity bias. There was a negative correlation between trait anxiety and positivity bias, r(124) = -0.21, p < .05.

We were motivated to explore the relationship between long-term and short-term forms of psychological strain (e.g., state anxiety, trait anxiety, and depressive symptoms) and positivity bias in episodic future thinking. We first hypothesized that individuals with state and trait anxiety, and depressive symptomatology would simulate future events with a more negative valence than those with lower levels of symptoms. Second, we hypothesized that individuals with state and trait anxiety, as well as symptoms of depression would imagine performing novel tasks less successfully than those with fewer symptoms. Findings demonstrated that individuals with higher scores of state and trait anxiety and depressive symptoms viewed imagined events with a more negative valence, thus supporting our first hypothesis and replicating the results of Study One.

Note. ** p < 0.01 (2-tailed); * p < 0.05; N = 126; PTS - Perceived Task Success

General Discussion

Investigating the relationship between Episodic Future Thought (EFT) and underlying symptoms or diagnosis of a psychological disorder has been a focus of research over the last decade. The primary goal of the current research was to extend this investigation into the realms of depression and both state and trait anxiety. Our aims were to examine the relationship of both temporary forms and lasting forms of psychological strain (i.e., state anxiety, trait anxiety, depressive symptoms) with how one envisions their performance of a novel future task, and to replicate findings of a relationship between perceived task performance, anxiety, and depressive symptoms.

Study One explored how state anxiety relates to perceived task success (e.g., successful or unsuccessful) and valence (i.e., positive, neutral, negative) in an imagined future scenario. As predicted, we found that individuals who experienced higher levels of state anxiety and more depressive symptoms tended to imagine performing novel future tasks less successfully than those who experienced fewer symptoms. Additionally, individuals with higher levels of state anxiety and depressive symptoms possessed a lower positivity bias when imagining future events than those with fewer symptoms. In other words, individuals who experience more internalizing symptoms tend to imagine performing future tasks through a more negative lens.

Study Two aimed to explore how trait anxiety relates to perceived task success (e.g., successful or unsuccessful) and valence (i.e., positive, neutral, negative) in an imagined future scenario, as well as sought to replicate the findings of Study One. As predicted, individuals who experienced higher levels of trait anxiety, state anxiety, and depressive symptoms demonstrated a lower positivity bias when imagining future events compared to those with fewer symptoms. The results of Study Two, however, did not demonstrate a relationship between temporary or lasting forms of psychological strain with perceived task success, despite there being a strong correlation between perceived task performance and positivity bias. Such findings partially replicate the results of Study One, which demonstrate a relationship between state anxiety, depressive symptoms, and positivity bias in EFT. These results also exhibit the extension of this relationship to more lasting forms of psychological strain (i.e., trait anxiety).

Our results parallel previous findings demonstrating how anxious individuals generate more negative experiences when imagining the future [17], while depressed individuals generate fewer positive scenarios when thinking about future outcomes [18]. Our findings imply that how one envisions their future could also be related to shortterm psychological strain (e.g., state anxiety, depressive symptoms). In other words, an individual’s mood and affect may relate to one’s ability to envision a positive future, depending on the extent of state anxiety or depressive symptoms experienced at that moment. These findings complement existing literature on internalizing symptoms and future outlook styles, given that past literature focuses on more severe, long-term forms of psychological strain, for instance, clinical disorders.

Study One demonstrated a more potent relationship between state anxiety, perceived task performance, and positivity bias than exhibited with depressive symptoms. A possible explanation may lie in how anxiety is specifically a future-oriented emotional state driven by the anticipation of future events [25]. Uncertainty is a significant driving force for anxiety, which diminishes effective and efficient preparation for the future; thus, anxiety is often invoked when outcomes of future events are intrinsically unknown [25]. The EFT cues developed and utilized were selected on the basis of novelty, with each scenario involving a new situational environment that most participants may have lacked experience with. Therefore, for those more susceptible to state anxiety, the general lack of familiarity that accompanied participants’ simulations may have contributed to a greater tendency to imagine unsuccessful outcomes to each cue.

Our research is the first to explore perceptions of task performance while investigating the relationship between EFT, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. There are many possible explanations as to why there may be a relationship between how one envisions performing a future task, state anxiety, and depressive symptoms. Many studies have linked low self-efficacy to anxiety and depression. Self-efficacy, a concept coined by psychologist Albert Bandura [26], refers to an individual’s belief in their competence or effectiveness in executing behaviors. Low levels of self-efficacy generally accompany higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptomatology. In contrast, individuals with a stronger sense of self-efficacy tend to be more resilient, less anxious, and less depressed [27, 28]. Given that anxious and depressed individuals tend to have lower self-efficacy, this may explain why participants with higher levels of state anxiety and depressive symptoms imagined performing future tasks less successfully than other participants. Individuals with higher levels of state anxiety and depressive symptoms may have had a weaker belief in their competency to execute each assigned task, resulting in less successful imagined simulations.

Potential limitations of our findings include the use of subjective self-report questionnaires. Additionally, given that these online surveys were administered to an undergraduate population, materials used were fitting for such a population. Events considered novel to a population with less life experiences may not be representative of populations with more life experiences. It is possible that some participants may have already experienced the event cues provided within the survey, which would influence their perceived task success and valence ratings positively given they would already have experience performing the task. Additionally, some particular cues utilized may have been objectively easier or more difficult to imagine, which would influence the success ratings within those particular scenarios.

There are many avenues of investigation for future research on EFT and psychological disorders. For instance, future research could aim to explore the driving factors that propel anxious and depressed individuals to pre-experience novel tasks in an unsuccessful manner. In addition, it may be valuable to explore how to leverage EFT as an intervention for reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms. Rehearsing positive and rational episodes of the future may facilitate long-term benefits for individuals who experience anxiety and depressive symptoms.

To our knowledge, this research is the first exploration of novel future task imagination and perceived success within anxiety and depressive symptoms. Our research extends the existing literature on EFT by highlighting the relationship between both temporary and lasting forms of psychological strain across future outlook styles. These findings emphasize how anxious and depressed individuals tend to naturally produce more negative episodes of the future, which provide significant clinical applications and open the door for future research.

Competing interest:

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

Tulving, E. (1985). Memory and consciousness. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 26(1), 1-12. View

Tulving, E. (1984). Précis of elements of episodic memory. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 7(2), 223-238. View

Gilbert, D. T., & Wilson, T. D. (2007). Prospection: Experiencing the future. Science, 317(5843), 1351–1354. View

Szpunar, K. K., Spreng, R. N., & Schacter, D. L. (2014). A taxonomy of prospection: Introducing an organizational framework for future-oriented cognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111, 18414–18421. View

Atance, C. M., & O'Neill, D. K. (2001). Episodic future thinking. Trends in cognitive sciences, 5(12), 533–539. View

Schacter, D. L., Benoit, R. G., & Szpunar, K. K. (2017). Episodic future thinking: Mechanisms and functions. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 17, 41–50.View

Arnold, A. E. G. F., Iaria, G., & Ekstrom, A. D. (2016). Mental simulation of routes during navigation involves adaptive temporal compression. Cognition, 157, 14-23.View

Dassen, C. M. F., Jansen, A., Nederkoorn, C., & Houben, K. (2016). Focus on the future: Episodic future thinking reduces discount rate and snacking. Appetite, 96, 327-322.View

O’Donnell, S., Daniel, T. O., & Epstein, L. H. (2017). Does goal relevant episodic future thinking amplify the effect on delay discounting? Consciousness and Cognition, 51, 10-16.View

Brown, G. P., MacLeod, A. K., Tata, P., & Goddard, L. (2002). Worry and the simulations of future outcomes. Anxiety Stress and Coping: An International Journal, 15(1), 1-17.View

Jing, H. G., Madore, K. P., & Schacter, D. L. (2016). Worrying about the future: An episodic specificity induction impacts problem solving, reappraisal, and well-being. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145(4), 402-418.View

Klinger, E., & Cox, W. M. (1987-1988). Dimensions of thought flow in everyday life. Imagination, Cognition and Personality 7(2), 105–128.View

Gilbert, D. T. (2006). Stumbling on happiness, New York: Knopf.

Hallford, D. J., Austin, D. W., Takano, K., & Raes, F. (2018). Psychopathology and episodic future thinking: A systematic review and meta-analysis of specificity and episodic detail. Behavior Research and Therapy, 102, 42–51. View

Hirschfeld, R. M. (2001). The comorbidity of major depression and anxiety disorders: Recognition and management in primary care. The Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 3(6), 244-254.View

Hirsch, C. R., & Matthews, A. (2012) A cognitive model of pathological worry. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(10), 636–646.View

MacLeod, A. K., & Byrne, A. (1996). Anxiety, depression, and the anticipation of future positive and negative experiences. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105(2), 286–289.View

MacLeod, A. K., & Salaminiou, E. (2001). Reduced positive future-thinking in depression: Cognitive and affective factors. Cognition and Emotion, 15(1), 99–107.

Wu, J. Q., Szpunar, K. K., Godovich, S. A., Schacter, D. L., & Hofmann, S. G. (2015). Episodic future thinking in generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 36, 1-8.View

Hallford, D. J., Barry, T. J., Austin, D. W., Raes, F., Takano, K., & Klein, B. (2020). Impairments in episodic future thinking for positive events and anticipatory pleasure in major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 260, 536—543.

Lalla, A., & Sheldon, S. (2021). The effects of emotional valence and perceived life stress on recalling personal experiences and envisioning future events. Emotion, 21(7), 1392-1401.View

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of general psychiatry, 4(6), 561-571. View

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. View

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, R., Vagg, P. R., & Jacobs, G. A. (1983). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Grupe, D. W., & Nitschke, J. B. (2013). Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: an integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(7), 488–501.View

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co.View

Bandura, A., Pastorelli, C., Barbaranelli, C., & Caprara, G. V. (1999). Self-efficacy pathways to childhood depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 258–269.View

Muris, P. (2002). Relationships between self-efficacy and symptoms of anxiety disorders and depression in a normal adolescent sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 32(2), 337-348.View