Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour Volume 7 (2024), Article ID: JMHSB-195

https://doi.org/10.33790/jmhsb1100195Research Article

Moderators of the Association Between Maternal Spanking and Behaviour Problems in At-Risk Black and White Children

Sara A. Moore*, Sandra Barnes, Anthony F. Greene, James E. Vivian, April E. Fallon, and Leanne J. Katz Levin

Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Psychology, Fielding Graduate University, 2020 De la Vina Street, Santa Barbara, California 93105, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Sara A. Moore, School of Psychology, Fielding Graduate University, 2020 De la Vina Street, Santa Barbara, California 93105, United States.

Received date: 24th November, 2024

Accepted date: 18th January, 2025

Published date: 20th January, 2025

Citation: Moore, S. A., Barnes, S., Greene, A. F., Vivian, J. E., Fallon, A. E., & Levin, L. J. K., (2025). Moderators of the Association Between Maternal Spanking and Behaviour Problems in At-Risk Black and White Children. J Ment Health Soc Behav 7(1):195.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

There is equivocal evidence as to whether physical discipline is more widespread within the Black community compared to a similar demographic White community. Our quantitative study investigated the association between caregiver’s use of spanking and externalizing behaviors among youth at ages 4, 6, 8, and 12. Race and gender were also examined as possible moderators of this relationship. The participants included 376 at-risk Black households (N = 265) and White households (N = 111) involved with the Longitudinal Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect (LONGSCAN) project. Results indicated that Black biological mothers reported spanking younger children more frequently than White biological mothers, while White mothers spanked older children more frequently than Black mothers. Significant but relatively small (r = .135 to r = .244) associations between the use of spanking and externalizing behavior were found at each age. Earlier use of spanking (at ages 4 and 6) was associated with externalizing behavior later in childhood (at age 8) and early adolescence (at age 12). Race moderated the relationship at ages 4, 8, and 12, with a positive association between spanking and externalizing behavior in Black households. The biological sex of the child did not influence the association between spanking and problem behavior. Our study adds to the discussion of racial differences in spanking and childhood outcomes using a developmental and identity-based cultural lens. Limitations and suggestions for future research are also presented.

Keywords: Corporal Punishment, Race and Development, Parenting Discipline Practices, Childhood Externalizing Behaviors, Ethnic and Cultural Differences

Introduction

Physical discipline is a prevalent and controversial parenting technique. The most common form of physical discipline is spanking, defined as hitting a child with an open hand on the buttocks or extremities with the intent to discipline without leaving a bruise or causing physical harm [1]. While spanking has been banned in some countries, it continues to be legal in the United States, although historical views on spanking have been shifting. While there was a higher acceptance of authoritarian parenting with attempts at behavioral management of children by spanking in previous decades, parental attitudes toward spanking have viewed it as less effective and less normalized more recently [2,3].

Researchers who study physical discipline say parents of all racial and ethnic groups, socioeconomic categories, and education levels practice some form of physical discipline with their children. A study conducted in 2011 found that 89% of Black parents, 79% of White parents, 80% of Hispanic parents, and 73% of Asian parents said they spanked their children [4]. A 2014 sample [5] found that Black families were more likely to engage in spanking of children between 0–9 years (59%) compared to White families (46%).

Trends in the use of corporal punishment in parenting have also changed over time. According to Finkelhor et al. [5], of a sample of American families, 49% of caregivers of children between the ages of 0–9 reported the occurrence of spanking, and 23% of children between the ages of 10–17 endorsed being spanked at least once the prior year. Spanking frequency was the highest between the ages of 3 and 4, with declines observed at age 7. These rates represented a decline in spanking of approximately 28% from the 1970s. Similarly, spanking prevalence among parents dropped from 50% in 1993 to 35% in 2017, with notable declines among children aged 2–4 years [6].

Whether spanking is an appropriate discipline strategy or a childrearing technique that is harmful to children has been a controversial debate. Existing literature on spanking is not free from systemic and historical biases, with research frameworks and interpretations often shaped by dominant cultural norms. These biases may influence how corporal punishment is conceptualized, studied, and interpreted. Acknowledging these biases is critical for fostering a more nuanced understanding of the complex interplay between cultural practices, societal norms, and child outcomes. Several decades of research indicate that childrearing practices involving physical discipline are associated with several mental health problems, including internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems, cognitive delays, as well as other maladaptive developmental problems in childhood [7,8].

Conversely, there is limited evidence that suggests that spanking is an effective means of behavioral management that does not result in unintended developmental consequences or lasting damage to children, although these studies are generally older and limited in scope [9-13]. Considering the overwhelming evidence of the potential ineffectiveness and adverse effects of physical punishment, the American Academy of Pediatrics [14] released a policy statement in December 2018 discouraging parents and guardians from using physical discipline. In 2019, the American Psychological Association [7] adopted a resolution condemning corporal punishment, including spanking. Multiple organizations have called for education, legislative reform, and additional research on this subject [7,15,16].

Some studies found that spanking is linked to more concurrent behavior issues in children [17-20]. Other analyses have identified spanking in childhood as a predictive factor for externalizing behavior over time and in subsequent years [17,21], including adolescence [22]. In one study, researchers found no evidence that spanking increased children’s conduct problems in the full sample. However, they found that infrequent, mild spanking was associated with decreased conduct problems [13]. A study by Speyer and colleagues [23] found that the effects of harsh parenting on child behavior changed as children grew. Specifically, harsh parenting did not significantly affect conduct problems in preschool-aged children, and its impact on emotional problems only appeared between ages 5 and 7. However, studies note that the precise causal link between spanking and behavior problems is complex and could be affected by unmeasured factors and that findings should be interpreted cautiously due to study limitations.

Given the literature suggesting that spanking may increase externalizing behavior in children, this study explores potential differences in the age when spanking occurs with regard to externalizing behaviors. Racial differences in the use of spanking were also examined. More specifically, do Black children who are spanked have different outcomes than White children who are spanked? Notably, existing research on racial differences in parenting practices often relies on binary racial categorizations, which may oversimplify the nuanced and diverse experiences within racial groups. Such approaches risk overlooking systemic inequities and historical contexts that profoundly influence parenting practices. This study acknowledges these limitations and aims to interpret its findings with sensitivity to the broader framework of structural inequities and negative racial stereotypes. Furthermore, this research examined the relationships between spanking, externalizing behaviors, biological sex, and age cohort.

Rationale/Theoretical Base

The cultural-ecological theory [24] posits that parenting strategies vary across cultural groups to help children adapt to their social context. Disciplinary techniques deemed appropriate in one culture may be viewed as harsh in another, reflecting differing goals for raising socially competent children. Parenting styles reflect family characteristics, cultural context, and socialization goals [24,25]. Parenting styles, shaped by diverse cultures, challenge using a single standard to define appropriateness [26]. Research highlights varied outcomes of physical discipline across racial groups [27,28]. A cultural-ecological framework helps explains why groups differ in parenting practices and how culture moderates spanking's effects on behavior.

Moderators

Why are some children who are physically disciplined more vulnerable to adverse outcomes, while others seem more resilient? Adequate assessment of the effects of physical discipline on children’s development requires considering the broader parenting context within which physical discipline occurs. Several researchers contend that outcomes regarding spanking are likely moderated by different contextual factors such as ethnicity and gender, often with varying results.

Some studies report a significant relationship between corporal punishment and behavior problems for White children, yet a weak or no relationship for Black children [27-30]. Others reflect a significant relationship between corporal punishment and more behavior problems for White children but fewer behavior problems for Black children [28,31]. Some studies found that Black adolescents who had been spanked as children had higher levels of externalizing behaviors [22]. Still, other studies report no association between physical discipline and behavior problems for Black children or White children [21,32-36]. To add to the body of literature, our study looked at the association between maternal spanking and externalizing behavior throughout childhood and over time and how that effect is moderated by race, specifically for White children and Black children and age cohorts (4, 6, 8, and 12).

Research on expectations for biological sex or gender differences on the potential impact of spanking on externalizing behavior is limited. The available evidence is mixed with some findings supporting moderated effect by child’s gender [20,37-39] and others finding no evidence of gender differences [21,40-42]. Furthermore, studies have used a variety of statistical methods to evaluate gender and spanking, including cross-lagged path [21,41] and structural equation modeling [20], while other studies controlled for gender [21,22]. Given the lack of clarity, this study sought to further examine whether the link between spanking and externalizing behavior differs by the gender of the child.

Therefore, our study investigated the impact of spanking on externalizing behavior by examining data collection points of youth at ages 4, 6, 8, and 12 to address the following hypotheses: 1). Within a sample of mothers of at-risk children, Black caregivers will have a higher frequency of physical discipline than their White counterparts; 2). Higher use of physical discipline by the mother will have a significant correlation with externalizing behaviors; 3). Race plays a role in moderating the relationship between the frequency of physical discipline and externalizing behavior; and 4). Biological sex plays a role in moderating the association between spanking and externalizing behavior.

Materials and Methods

Our correlational study used longitudinal archival data to assess spanking and externalizing behaviors among youth who were at risk for maltreatment during childhood. Hayes’ PROCESS regression analyses were utilized to examine and determine whether race or gender moderated the effects of spanking on externalizing behavior. Our decision to test for moderation was based on an interest in whether there is a relationship between the independent and dependent variables. Research suggests there may be mixed results regarding the impact of spanking, particularly for various groups. Therefore, we hypothesized that contextual factors alter these outcomes. Our study explored the association of spanking with externalizing behavior when race and gender are taken into account. Specifically, we sought to examine what happens in the relationship between spanking and externalizing behavior across childhood when race and gender are considered.

Participants

Our study utilized data from the Longitudinal Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect (LONGSCAN), which is a five-site consortium established in 1990 conducting a longitudinal study of the etiology and impact of child maltreatment [43]. A sample of N = 376 households from the LONGSCAN dataset was targeted for the investigation. Self-reporting of race was included in the LONGSCAN research protocol and participants were categorized as White, Black, Hispanic, Native American, Asian, Mixed Race, or Other. In this study, households were included in which the caregiver/respondent was the biological mother and the same race of either a male or female Black child (N = 265) or White child (N = 111) child from birth to at least 12 years of age. Families of other races or where race was missing were excluded. For the primary analyses, history of physical abuse/maltreatment was treated as a covariate. It is important to note that the LONGSCAN dataset primarily represents low-income, at risk populations, specifically children who have experienced or are at high risk for child abuse and neglect.

Measures

Demographic Information: The Caregiver Demographics Scale (CDS) was utilized to determine race and child gender. Basic demographic information was collected at the age 4 interviews with LONGSCAN participants and their caregivers and updated at subsequent interviews. Caregivers reported on the race and gender of the child. Caregiver race was assessed via the item: “Looking at this card, please tell me your racial or ethnic background.’ Response options included White, Black, Hispanic, Native American Indian, Asian, Mixed Race, or Other (specify).” Child demographics were with a similar item. Child “gender” was reported using the item: “Child’s gender,” with two response options: “Male” or “Female.” The LONGSCAN dataset relied on caregiver-reported gender, which likely reflects biological sex as perceived by the caregiver. This approach reflects the binary categorization common in early 1990s research protocols. We acknowledge the importance of distinguishing between gender identity and biological sex in contemporary research and recommend future studies use measures that capture these distinctions.

Physical Discipline (Spanking): Portions of the Parent-Child version of the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-PC) [44] were administered to caregivers to assess levels of physical discipline toward the child at ages 4, 6, 8, and 12. The CTS-PC measures the extent to which a parent has carried out specific acts of physical and psychological aggression, regardless of whether the child is injured. The core scales of the CTS-PC include Nonviolent Discipline, Psychological Aggression, and Physical Assault. The core scales of the CTS-PC have adequate internal consistency with an alpha of .55 to .70 [44]. Straus and colleagues [44] report that the interrelations of the scales and their correlations with selected demographic variables support the construct validity of the scales. In the current study, one item— spanking— was assessed via the item: “How many times in the past year, when you have had a problem with the child, did you spank him/her?” Response options included: Never, Once, Twice, 3–5 times, or >5 times. At age 8, the timeframe for recall was adjusted to six months. At age 12, the revised Conflicts Tactics Scale was introduced [44]. The specific item used to assess spanking asked, “In the past year how often have you: Spanked him/ her on the bottom with hand.” Response options included: This has never happened, Once, Twice, 3-5 Times, 6-10 Times, 11-20 Times, > 20 Times, Not in the past year but it did happen before. While the CTS-PC is a widely used and validated tool, the reliance on single-item measures to assess spanking limits the validity of interpretation and may not fully capture the broader context, severity, or intent behind the act of spanking, introducing potential measurement error. Nonetheless, this item was chosen as the best available measure in the dataset for this specific category of physical discipline.

Externalizing behaviors: The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) measured externalizing behaviors among the youth by analyzing scores on the Externalizing Behaviors scale as reported by the caregiver to report on externalizing symptoms of delinquency, aggressive behaviors, and social competence. The CBCL is one of the most commonly used measures of child psychopathology. The measure has been normed on a national sample and is a reliable measure for capturing Externalizing Behavior Problems, with an alpha of 0.93 [45]. The CBCL was used with the LONGSCAN population at ages 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 at all five sites. Although, this study examined data collection points at ages 4, 6, 8, and 12. The content, construct, and criterion-related validity of the CBCL instrument are also well documented. The criterion validity of the CBCL has been demonstrated by its ability to discriminate between clinic-referred and non-referred children [45]. The broadband raw score for Externalizing Behavior Problems was used in the current study as the major child outcome variable. The clinical range cutoff score of T>63 was used to designate clinically significant externalizing problems.

Procedures: Common measurement protocols and procedures were developed by the LONGSCAN consortium to address multiple questions related to risk and protective factors for child maltreatment and subsequent outcomes. This retrospective study involving human participants was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Human Investigation Committee (IRB) of Fielding Graduate University approved this study. After obtaining Fielding Graduate University IRB approval and gaining permission to access the LONGSCAN dataset, analyses of the data were conducted. All incidents of abuse were considered, including alleged and/or substantiated Child Protective Services (CPS) reports, to control for maltreatment. Race was dummy coded with only White and Black groups considered as the focus of this study.

Results

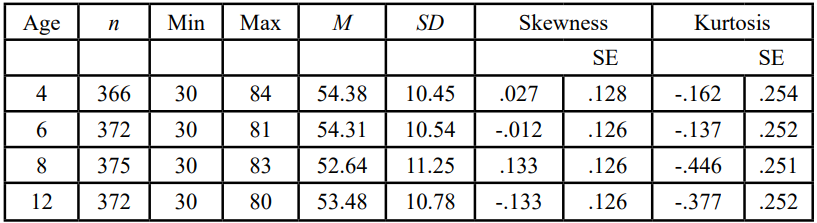

A sample of N = 376 households from the LONGSCAN dataset was targeted for the investigation. Households were included in which the caregiver/respondent was the biological mother of either a Black child or White child (male or female) from birth to at least 12 years of age. The sample included only cases where child and caregiver race matched (Black/White). Other racial categories were excluded to target Black households and White households specifically. Our analysis yielded a final sample of 376 households. Characteristics of the target sample can be found in Table A1. Overall, the sample of households was disproportionately Black (70.5%). White households appeared to be proportionately more likely to include a male child (54.1) and Black households to include a female child (54.3). The association between household race and child gender was not significant χ2(1) = 2.21, p = .137. Distributions of CBCL externalizing behavior scores were examined at each age (see Table 2A).

Spanking in Black Households and White Households

The study employed a combination of ANCOVAs, partial correlations, and moderation analyses using Hayes’ PROCESS macro. While these methods are standard for examining group differences and moderation, more advanced methods, such as cross-lagged panel models or random intercept cross-lagged models, could account for stability, bidirectionality, and within-person versus between-person effects, although these approaches were not used due to the scope of the current project and the challenges in applying these techniques to a dataset originally designed for a different purpose. Despite this limitation, the approach allows for an exploration of immediate and lagged associations between spanking and externalizing behavior, as well as the moderating effects of race and gender.

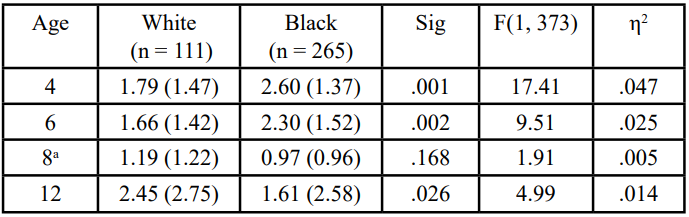

To examine the hypothesis that spanking was used more frequently in Black households than in White households, we ran a series of single factors ANCOVAs. For each analysis, the racial composition of the household (Black/White) served as the independent variable, and the frequency of spanking at each age served as the dependent variable. History of allegations of physical abuse was treated as a covariate in all analyses. Results can be found in Table A3.

Consistent with our hypothesis, significantly more spanking was reported in Black households than in White households at ages 4 and 6. No significant differences were observed at age 8. Conversely, at age 12, significantly more spanking was reported in White households than in Black households.

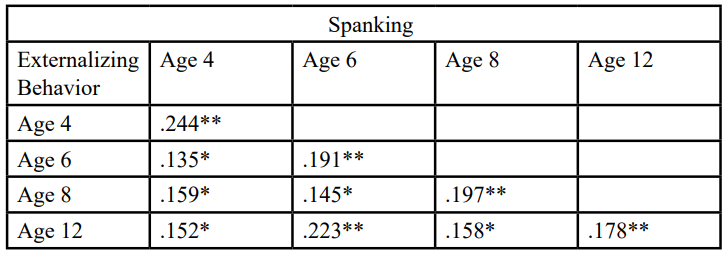

The Association between Spanking and Externalizing Behavior

To examine the association between spanking and externalizing behavior, a series of partial correlations were run, controlling for a history of physical abuse allegations. Results are presented in Table A4. Significant, though fairly small, correlations were consistently found between spanking and externalizing behavior (r = .135 to .244). As seen in Table A4, this finding held true when the association was examined contemporaneously (e.g., age 4 spanking with age 4 externalizing behavior) and when spanking at earlier ages was associated with externalizing behavior at later ages. Although small, all of the correlations were significant, consistent with the hypothesis that spanking and externalizing behavior are positively associated.

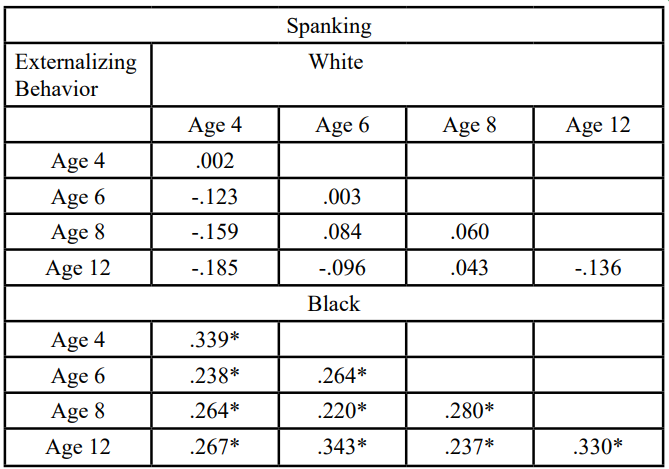

Bivariate correlations between spanking and externalizing behavior were also examined separately in the Black households and White households (see Table A5). When this was done, significant correlations were consistently obtained in the Black households (r = .220 to .339) but not in the White households where no significant correlations were obtained (r = .002 to -.185).

Table A5: Bivariate Correlations between Spanking and Externalizing Behavior in White Households and Black Households

Does Race of Household or Child Sex Moderate the Association between Spanking and Externalizing Behavior?

The hypothesis concerning the moderating effects of household race was examined further. Table A6 presents results pertaining to hypotheses concerning the moderating effects of race and child gender on the association between spanking and externalizing behavior. A regression-based approach to these analyses was used (the PROCESS macro) [46] by which evidence of moderation takes the form of a significant (spanking by race) interaction effect. Significant interaction effects were then probed with simple slopes analysis where the effect of interest (the association between spanking and externalizing behavior) was examined at the different levels of the moderator (White/Black households; male/female child). In each of the models tested, history of physical abuse was treated as a covariate.

The first series of (4) analyses examined the moderating roles of household race and child gender in models that matched the age at which spanking and externalizing behavior were measured. The second series of (4) analyses were intended to examine longer-term effects of spanking at younger ages (4 and 6) on externalizing behavior later in childhood (age 8) and early adolescence (age 12). As seen in Table A6, significant spanking by race interaction effects were obtained at ages 4, 8, and 12. Examination of the conditional effects indicated, further, that the race of the household appeared to moderate the effects of spanking on externalizing behavior in essentially the same way across these ages. In each case, there was a significant, positive association between spanking and externalizing behavior in the Black households but not in the White households. For instance, the significant race-by-spanking interaction at age 4 (p < .01) indicates that the relationship between spanking and externalizing behavior is positive in Black households but not significant in White households. These conditional effects underscore the potential moderating role of race in shaping these associations.

Table A6: The Moderating Effects of Household Race and Child Gender on the Association between Spanking and Externalizing Behavior

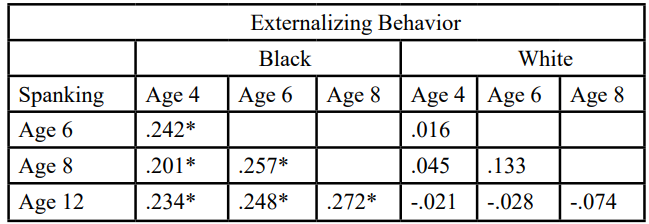

The second set of (4) analyses were intended to apply a developmental lens to these data by examining the moderating effects of race on the association between spanking at younger ages (4 and 6) and externalizing behavior during later childhood (age 8) and early adolescence (age 12). Race of the household continued to function as a moderator of the effects of spanking (at younger ages) on externalizing behavior (later in childhood/adolescence). As before, there were significant, positive associations between early spanking (ages 4 and 6) and externalizing behavior at ages 8 and 12 in the Black households but not the White households.

Further analysis was conducted to explore the possible direction of the relationship between spanking and externalizing behavior and to aid in our understanding of the moderating effects of household race that emerged. As already seen, spanking at earlier ages predicted (was associated with) externalizing behavior at later ages (see Tables A4 and A5), and this effect appeared to be restricted to Black households. Because the data are correlational, it is possible that externalizing behavior at earlier ages also predicts spanking at later ages. When these correlations are examined, it becomes clear that the association between earlier externalizing behavior and later spanking are, once again, restricted to Black households. As seen in Table A7, in the Black households, externalizing behavior at age 4 was associated with spanking at ages 6, 8, and 12. Externalizing behavior at age 6 was associated with spanking at ages 8 and 12, and so on. No such associations were observed in the White households.

Table A7: The Associations Between Early Spanking on Later Externalizing Behavior Moderated by Household Race

When the outcome included only the clinical range (CR) on the CBCL (T>63), the same pattern was also found. Prevalence of scores in the clinical range by age cohort were as follows: Age 4 – 62 (16.9%); Age 6 – 69 (18.5%); Age 8 – 70 (18.7%); Age 12 – 70 (18.8%). The link between spanking and externalizing behavior was found exclusively in Black households. The results closely parallel those found with the T-scores from the CBCL, particularly when using spanking at younger ages of 4 and 6 to predict clinical range externalizing behavior at ages 8 and 12.

A similar set of analyses, treating child biological sex/gender (female/male) as the moderator revealed no significant spanking by gender interaction effects. With this targeted sample, there was no evidence that the association between spanking and externalizing behavior was different for girls or boys.

Discussion

Our study sought to add to the literature examining race and gender differences in the association between spanking and problem behavior in children through cultural and developmental lenses in a sample of at-risk households. The purpose is to contribute to the existing literature by providing insights into cultural factors that may shape disciplinary practices and their consequences for child development. We aimed to highlight any nuanced relationships between spanking and child outcomes, emphasizing the importance of understanding cultural contexts in interpreting disciplinary strategies. The intention is not to support or condone corporal disciplinary practices. Instead, we hope to contribute to efforts to promote culturally informed research and effective and nurturing parenting practices that support optimal development and positive outcomes for children, considering the complexities, trends, and diverse perspectives involved in disciplinary practices.

Our first hypothesis was partially supported in that more spanking was reported in Black households than in White households at ages 4 and 6, but no differences were found at age 8. Conversely, at age 12, more spanking was reported in White households than in Black households. These findings suggest that cultural norms and societal expectations surrounding spanking may differentially influence its prevalence and perception across different stages of childhood and racial groups. Given these findings, the variations in spanking reported between Black households and White households at different ages may be influenced by several factors, including cultural norms and developmental changes. In Black households, spanking was more prevalent at ages 4 and 6, potentially as part of a culturally embedded approach to instill obedience and respect early in life [47,48]. Black caregivers might use spanking as a proactive measure, aiming to equip their children with the discipline necessary to navigate a society that may judge them more harshly. As these children grow and gain a better understanding of social expectations, these findings suggest their parents may shift towards other forms of discipline, decreasing the reliance on spanking. Conversely, the increase in spanking reported in White households at age 12 could reflect a response to the challenges associated with preadolescence, where children assert more independence and might provoke stricter disciplinary measures from parents. This shift could also be influenced by societal expectations and perceptions that evolve as children grow, with parents adjusting their disciplinary methods in reaction to changing behaviors and societal pressures. Further research is needed to confirm and fully understand these relationships.

Our study also found a positive association between reports of spanking and the child’s externalizing behavior among Black families. Children who were spanked exhibited more problem behavior, consistent with prior research, while also underscoring the complex relationship between disciplinary practices and child outcomes [17,18]. The directionality of this association remains unclear as to whether physical discipline is an antecedent to subsequent increases in aggressive behavior or whether aggressive behavior leads to increased spanking. Recent research suggests a causal relationship may exist, but more research is needed to replicate those findings [49].

There has been a proliferation of research concerning the effects of physical discipline on early child development. Studies have revealed that frequent and ongoing physical discipline in early childhood was positively related to childhood aggression [17-20] Our study added some support for such with small but significant effects similar to those found in other studies. The correlation between spanking and externalizing behavior is intricate and does not suggest causality. Patterson’s coercion model suggests a cyclical pattern where child misbehavior may provoke harsher parenting responses, potentially exacerbating behavior issues [50]. There is still much to learn to better understand why some children who are physically disciplined are particularly vulnerable to negative outcomes and others seem more resilient.

As hypothesized, the effects of spanking on externalizing behavior were different depending on race. Our study found that spanking in Black households, but not White households, was associated with more externalizing behavior in children at ages 4, 8, and 12. This pattern was consistently found, albeit with small effects, when examining the data in several ways, including at each age period, as earlier spanking on later problem behavior, and as a predictor of being in the Clinical Range of externalizing behavior in later ages. The small effect sizes observed in our study raise questions about the practical significance of these findings, despite their statistical significance. These results may indicate that while spanking contributes to behavioral outcomes, other contextual and developmental factors could play a more substantial role in shaping child behavior. Several researchers contend that outcomes regarding spanking can be moderated by different contextual factors such as race and gender [18,20,22]. These studies that examined racial disparities in spanking did not comment on the potential reasons for this [18]. In our study, variations in how spanking is related to externalizing behaviors suggests differential impacts based on identity-based cultural factors, although it remains unclear explicitly why.

It is also critical to consider the potential measurement errors and limitations inherent in the constructs and items used in this study. Spanking was assessed using a single self-report item, which likely does not capture the nuances of this behavior, such as the context, severity, or intent of the discipline. This limited measure may introduce error, as caregivers may interpret the term “spanking” differently based on cultural or individual experiences. Similarly, race and gender were assessed using single-item measures, with limited options for self-identification and no inclusion of non-binary or multi-racial categories. The use of such measures reflects the structure of the dataset and constraints of the early 1990s, when the data were first collected, rather than a dismissal of the broader heterogeneity within and across racial groups, but they do not align with contemporary understandings of these complex constructs. For example, the binary categorization of race used in this study does not capture the full complexity of racial identity, nor does it account for the broader systemic and historical contexts influencing these parenting practices. Future research should employ multi-item measures and more inclusive approaches to ensure greater reliability and validity of the findings.

Furthermore, caregiver self-reports are susceptible to biases, such as social desirability bias, particularly in contexts where spanking may be stigmatized. White caregivers, for example, may underreport spanking due to cultural norms that discourage physical discipline, while Black caregivers may overreport spanking, either due to different cultural attitudes or assumptions about its acceptability. These potential inaccuracies in reporting highlight the need for caution when interpreting these findings. The reliance on self-reports for spanking introduces the possibility that racial differences in spanking frequency and its association with externalizing behaviors could, in part, reflect differences in reporting practices rather than actual behaviors. Future studies should consider incorporating independent observations or alternative reporting methods to mitigate these biases. Future research should strive to include diverse perspectives and avoid confirmation biases that may reinforce existing stereotypes or overlook alternative interpretations. This is particularly important in examining the complex interplay of cultural, contextual, and systemic factors in parenting practices.

As parenting styles are indeed shaped by diverse cultures [26], using a cultural ecological framework [24] can clarify how culture acts as a filter that can ease or exacerbate the effects of physical discipline on child behavior. Focus groups performed by Duong et al. [51]revealed that when discussing corporal punishment of their children, Black parents called on their experiences with corporal punishment as a child. In contrast, White parents framed their perceptions based on their peers when spanking was perceived as positive and normative. These findings are consistent with research suggesting that parental attitudes toward spanking may influence how children perceive punishment as unfair versus appropriate [21,52]. Children’s perception of discipline may then influence subsequent behaviors. Future research should continue this exploration and examine children’s interpretations and meanings attached to disciplinary practices, an aspect not captured in the LONGSCAN data, to deepen our understanding of how disciplinary strategies influence child behavior.

Among the sample in our study, the child’s gender did not moderate the association between spanking and externalizing behavior. This finding did not support our hypothesis but was similar to prior research [21,40-42]. Thus, this research suggests the relationship between spanking and problem behavior may not differ based on the child’s gender and does not add to the support for gender effects.

Our findings highlight associations between spanking and negative child outcomes and contribute to the growing body of research on spanking and child development. However, the nuanced relationship between spanking, children’s current and future problem behaviors, and how it varies by race calls for a cautious interpretation of our findings. Furthermore, we do not support or condone spanking as an effective or harmless parenting strategy. While our study contributes to the growing body of research on spanking and child development, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations. This study’s participants were youth involved with the LONGSCAN study due to high-risk potential for maltreatment. This factor could potentially affect external validity and generalizability of the results. Possible confounding factors in this study could include the at-risk nature of the participants’ families and unique characteristics of each youth. In addition, relationships found in the present study are primarily with low socioeconomic status (SES) and at-risk families.

The sample for our analysis was restricted only to caregivers who were the biological mother and matched the child’s race. While this was done to minimize the undue influence of other factors, it is a limitation to the generalizability of the study. For instance, households where the biological mother was consistently available to the child over time could differ from households with other types of caregivers. Maternal spanking could feasibly produce different effects than other caregiver spanking, which our study did not explore.

Furthermore, it should not be assumed that Black households are a homogeneous group. It is essential to avoid oversimplifying these complex issues and recognize the historical and social contexts that influence parenting practices within different communities. Pathologizing racially diverse parenting strategies and applying a single cultural lens should be avoided, given the heterogeneity within cultural groups and the varying intents and contexts of childrearing practices [20]. To further understand the impact of spanking on Black children, it might be useful to conduct a within-group investigation of the general population to explore whether socioeconomic or social/racial subgroup variability moderates the impact of spanking on externalizing behavior. Understanding the correlates of cultural identity that influence these effects would be a useful direction for future studies. Research that looks at other racial groups is also warranted.

In our study, spanking was measured based on one parent-report item. Therefore, the interpretation and reporting of spanking was left to the interpretation of the caregiver. At age 8, the timeframe for recall of spanking was reduced from one year to six months. While the Conflict Tactics Scale – Parent-Child (CTS-PC) is widely used, this limitation may introduce measurement error, potentially attenuating observed associations between spanking and child outcomes. Future research should consider alternative measures or statistical techniques, such as latent variable modeling, to account for this limitation. In addition, there may be individual and cultural differences in what is perceived and reported as spanking. Independent raters could be used in future studies to reduce bias. Consistent with prior research [22], our study controlled for the effects of physical abuse by treating physical abuse and maltreatment allegations as a covariate. It is possible that this may have resulted in an underestimation of the impact of spanking, particularly since research suggests that more severe forms of punishment are associated with an increased risk of negative effects [53].

Future research could examine the cumulative effects of spanking over time to see if race and gender influence the relationship between spanking and problem behavior in children. Other studies have identified potential moderators between spanking and externalizing behaviors, including family cohesion, maternal warmth, and religiosity [54-56]. Identification of protective factors is another area for future research. It would also be useful to understand what specific discipline practices may have the desired effects on improving functioning in childhood with a consideration of cultural influences so these childrearing practices can be offered as an alternative to encourage healthier developmental outcomes.

In conclusion, while acknowledging the complexities of the subject matter and limitations of our study, the findings underscore the significance of identity-based cultural factors in shaping the dynamics of spanking and its consequences for child behavior. Efforts to promote effective and nurturing parenting practices should consider these contextual factors and diverse perspectives to support positive outcomes for children.

Declarations

Competing Interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Gershoff, E. T., & Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2016). Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(4), 453–469. View

Alampay, L. P., Godwin, J., Lansford, J. E., Oburu, P., Bornstein, M. H., Chang, L., Deater-Deckard, K., Rothenberg, W. A., Malone, P. S., Skinner, A. T., Pastorelli, C., Sorbring, E., Steinberg, L., Tapanya, S., Uribe Tirado, L. M., Yotanyamaneewong, S., Al-Hassan, S. M., Bacchini, D., Di Giunta, L., Dodge, K. A., & Gurdal, S. (2022). Change in caregivers’ attitudes and use of corporal punishment following a legal ban: A multi-country longitudinal comparison. Child Maltreatment, 27(4), 561-571. View

Lansford, J., Zietz, S., Al-Hassan, S., Bacchini, D., Bornstein, M., Chang, L., Deater-Deckard, K., Di Giunta, L., Dodge, K., Gurdal, S., Liu, Q., Long, Q., Oburu, P., Pastorelli, C., Skinner, A., Sorbring, E., Tapanya, S., Steinberg, L., Uribe Tirado, L. Yotanyamaneewong, L., & Alampay, L. (2021). Culture and social change in mothers’ and fathers’ individualism, collectivism and parenting attitudes. Social Sciences, 10(12), 459.View

Siek, S., (2011). Researchers: African-Americans most likely to use physical discipline. Retrieved from https:// www.cnn.com/2011/11/10/us/researchers-african-americans-most-likely-to-use-physical-punishment/ index.html#:~:text=Researchers%20said%20African%20 Americans%20are,%2C%20whipping%2C%20 whupping%2C%20spanking.

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., Wormuth, B. K., Vanderminden, J., & Hamby, S. (2019). Corporal punishment: Current rates from a national survey. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(7), 1991-1997. View

Mehus, C. J., & Patrick, M. E. (2021). Prevalence of spanking in US national samples of 35-year-old parents from 1993 to 2017. JAMA pediatrics, 175(1), 92-94. View

American Psychological Association (APA, 2019). Resolution on physical discipline of children by parents. View

Gershoff, E. T. (2013). Spanking and child development: We know enough now to stop hitting our children. Child Development Perspectives, 7: 133–137. View

Baumrind, D. (1996a). A blanket injunction against disciplinary use of spanking is not warranted by the data. Pediatrics, 98, 828–831.View

Baumrind, D. (1996b). The discipline controversy revisited. Family Relations, 45, 405–415. View

Larzelere, R. E. (1996). A review of the outcomes of parental use of nonabusive or customary physical punishment. Pediatrics, 98(4), 824–828.View

Larzelere, R. E. (2000). Child outcomes of nonabusive and customary physical punishment by parents: An updated literature review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 3(4), 199-221. View

Pritsker, J., (2021). Spanking and externalizing problems: Examining within-subject associations. Child development, 92(6), 2595–2602.View

Sege, R. D., Siegel, B. S., Council on Child Abuse and Neglect, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health (2018). Effective discipline to raise healthy children. Pediatrics, 142(6).View

Durrant, J. E., Stewart-Tufescu, A., & Afifi, T. O., (2020). Recognizing the child’s right to protection from physical violence: An update on progress and a call to action. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110, 104297. View

Foston, B. L., Klevens, J., Merrick, M. T., Gilbert, L., & Alexander, S. P., (2016). Preventing child abuse and neglect: A technical package for policy, norm, and programmatic activities. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (U.S.). Division of Violence Prevention. View

Gershoff, E. T., Sattler, K. M. P., & Ansari, A., (2018). Strengthening causal estimates for links between spanking and Children’s externalizing behavior problems. Psychological Science, 29(1), 110-120. View

Grogan-Kaylor, A., Ma, J., Lee, S. J., Castillo, B., Ward, K. P., & Klein, S., (2018). Using bayesian analysis to examine associations between spanking and child externalizing behavior across race and ethnic groups. Child Abuse & Neglect, 86, 257- 266. View

Pinquart, M., (2021). Cultural differences in the association of harsh parenting with internalizing and externalizing symptoms: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(12), 2938-2951. View

Turns, B. A., & Sibley, D. S., (2018). Does maternal spanking lead to bullying behaviors at school? A longitudinal study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(9), 2824-2832. View

MacKenzie, M. J., Nicklas, E., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Waldfogel, J. (2015). Spanking and children’s externalizing behavior across the first decade of life: Evidence for transactional processes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(3), 658-669. View

Gibson, C. L., & Fagan, A. A. (2018). An individual growth model analysis of childhood spanking on change in externalizing behaviors during adolescence: A comparison of whites and African American’s over a 12-year period. The American Behavioral Scientist (Beverly Hills), 62(11), 1463-1482. View

Speyer, L. G., Hang, Y., Hall, H. A., & Murray, A. L. (2022). The role of harsh parenting practices in early- to middle-childhood socioemotional development: An examination in the millennium cohort study. Child Development, 93(5), 1304-1317. View

Ogbu, J.U. (1985). A cultural ecology of competence among inner-city Blacks. In: Spencer, M.B., Brookins, G.K., & Allen, W.R. (Eds.). Beginnings: The social and affective development of Black children. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 44-66. View

Bulcroft R.A., Carmody D.C., & Bulcroft K.A. (1996). Patterns of parental independence giving to adolescents: Variations by race, age, and gender of child. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 866–883. View

Whaley, A. (2000). Sociocultural differences in the developmental consequences of the use of physical discipline during childhood for African Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 6(1), 5-12. View

Deater-Deckard, K., Dodge, K. A., Bates, J., & Pettit, G. (1996). Physical discipline among African American and European American mothers: Links to children’s externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 32(6), 1065–1072. View

Lansford, J.E., Deater-Deckard, K., Dodge, K.A., Bates, J.E., & Pettit. G.S. (2004). Ethnic differences in the link between physical discipline and later adolescent externalizing behaviors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(4), 801-812. View

Kang, S., Gair, S. L., Paton, M. J., & Harvey, E. A. (2023). Racial and ethnic differences in the relation between parenting and preschoolers’ externalizing behaviors. Early Education and Development, 34(4), 823-841. View

McLeod, J. D., & Nonnemaker, J. M. (2000). Poverty and child emotional and behavioral problems: Racial/Ethnic differences in processes and effects. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41(2), 137-161. View

Gunnoe, M. L., & Mariner, C. L. (1997). Toward a developmental-contextual model of the effects of parental spanking on children's aggression. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 151(8), 768–775. View

Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2004). The effect of corporal punishment on antisocial behavior in children. Social Work Research, 28(3), 153–162. View

Ma, J., & Klein, S. (2018). Does Race/Ethnicity moderate the associations between neighborhood and parenting processes on early behavior problems? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(11), 3717-3729. View

McLeod, J. D., & Shanahan, M. J. (1993). Poverty, parenting, and children's mental health. American Sociological Review, 58(3), 351-366. View

Scott, J. K., Simons, C., & Harden, B. J. (2023). African American, low‐income mothers’ negative emotional reactivity, punishment, and children’s externalizing and internalizing behavior. Family Relations, 72(4), 1656-1674. View

Ward, K. P., Lee, S. J., Limb, G. E., & Grogan-Kaylor, A. C. (2021). Physical punishment and child externalizing behavior: Comparing American Indian, White, and African American children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(17-18), NP9885-NP9907. View

Miner, J. L., & Clarke-Stewart, K. A. (2008). Trajectories of externalizing behavior from age 2 to age 9: Relations with gender, temperament, ethnicity, parenting, and rater. Developmental Psychology, 44(3), 771-786. View

Rubin, K., Burgess, K., Dwyer, K., & Hastings, P. (2003). Predicting preschoolers’ externalizing behaviors from toddler temperament, conflict, and maternal negativity. Developmental Psychology, 39(1), 164-176. View

Shoenberger, N., & Rocheleau, G. C. (2017). Effective parenting and self-control: Difference by gender. Women & Criminal Justice, 27(5), 271-286. View

MacKenzie, M. J., Nicklas, E., Waldfogel, J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2012). Corporal punishment and child behavioural and cognitive outcomes through 5-Years of age: Evidence from a contemporary urban birth cohort study. Infant and Child Development, 21(1), 3-33. View

O'Gara, J. L., Calzada, E. J., LaBrenz, C., & Barajas-Gonzalez, R. G. (2020). Examining the longitudinal effect of spanking on young Latinx child behavior problems. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(11), 3080–3090. View

Rothbaum, F., & Weisz, J. R. (1994). Parental caregiving and child externalizing behavior in nonclinical samples: A meta analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 116(1), 55-74. View

Runyan, D. K., Curtis, P. A., Hunter, W. A., Black, M. M., Kotch, J. B., Bangdiwala, S., Dubowitz, H., English, D., Everson, M. D., & Landsverk, J. (1998). LONGSCAN: A consortium for longitudinal studies of maltreatment and the life course of children. View

Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Finkelhor, D., Moore, D. W., & Runyan, D. (1998). Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(4), 249–270. View

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). The Child Behavior Checklist and related instruments. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment, 429–466. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. View

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (methodology in the social sciences) (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. View

Silveira, F., Shafer, K., Dufur, M. J., & Roberson, M. (2021). Ethnicity and parental discipline practices: A cross-national comparison. Journal of Marriage and Family, 83(3), 644-666. View

Thomas, K. A., & Dettlaff, A. J. (2011). African American families and the role of physical discipline: Witnessing the past in the present. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 21(8), 963-977. View

Barbaro, N., Connolly, E. J., Sogge, M., Shackelford, T. K., & Boutwell, B. B. (2023). The effects of spanking on psychosocial outcomes: Revisiting genetic and environmental covariation. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 19(3), 713-742. View

Patterson, G. R. (2002). The early development of coercive family process. In J. B. Reid, G. R. Patterson & J. Snyder (Eds.), Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention (pp. 25-44). American Psychological Association. View

Duong, H. T., Monahan, J. L., Mercer Kollar, L. M., & Klevens, J. (2022). Examining sources of social norms supporting child corporal punishment among low-income black, latino, and white parents. Health Communication, 37(11), 1413-1422. View

Lansford, J. E. (2010). The special problem of cultural differences in effects of corporal punishment. Law and Contemporary Problems, 73(2), 89-106. View

Ferguson, C. J. (2013). Spanking, corporal punishment and negative long-term outcomes: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(1), 196- 208. View

Lansford, J. E., Sharma, C., Malone, P. S., Woodlief, D., Dodge, K. A., Oburu, P., Pastorelli, C., Skinner, A. T., Sorbring, E., Tapanya, S., Tirado, L. M. U., Zelli, A., Al-Hassan, S. M., Alampay, L. P., Bacchini, D., Bombi, A. S., Bornstein, M. H., Chang, L., Deater-Deckard, K., & Di Giunta, L. (2014). Corporal punishment, maternal warmth, and child adjustment: A longitudinal study in eight countries. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 43(4), 670-685. View

Lee, Y., & Watson, M. W. (2020). Corporal punishment and child aggression: Ethnic-level family cohesion as a moderator. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(15-16), 2687-2710. View

Petts, R. J., & Kysar-Moon, A. E. (2012). Child discipline and conservative Protestantism: Why the relationship between corporal punishment and child behavior problems may vary by religious context. Review of Religious Research, 54(4), 445- 468.View