Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour Volume 7 (2025), Article ID: JMHSB-196

https://doi.org/10.33790/jmhsb1100196Research Article

Retracted: Fatherhood in Context: Intergenerational, Psychological, and Relational Influences

Cassandra L. Bolar1*, Heather A. Jones2, and Margaret K. Keiley3

1Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, School of Social Sciences, University of West Georgia, United States.

2School of Social Work, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, United States.

3Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Auburn University, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Cassandra L. Bolar, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, School of Social Sciences, University of West Georgia, 1601 Maple Drive, Carrollton, GA 30118. United States.

Received date: 11th September, 2024

Accepted date: 15th February, 2025

Published date: 17th February, 2025

Citation: Bolar, C. L., Jones, H. A., & Keiley, M. K., (2025). Fatherhood in Context: Intergenerational, Psychological, and Relational Influences. J Ment Health Soc Behav 7(1):196.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

The current study examined a process model for father involvement that incorporated important contextual factors that have salient influence on paternal engagement. The proposed process model also included developmental outcomes for children. Longitudinal data from the Future of Families and Child Wellbeing Study was used to examine an adapted version of Belsky’s (1984) process model for the determinants of parenting. Fathers’ past involvement with their own fathers was negatively related fathers’ depression when their children were born. Furthermore, when children were newborns, paternal depression was negatively related to fathers’ intimate relationship quality with birth mothers. The most robust relationships were the following: a positive relationship between fathers’ intimate relationship quality when their children were born and later father involvement when their children were 3 years old; and a positive relationship between fathers’ intimate relationship quality when their children were newborns and later intimate relationship quality when children were 3 years old. Lastly, father involvement, intimate relationship quality, and the interaction between father involvement and intimate relationship quality when children were 3 years old significantly predicted child outcomes (pro-social, internalizing, and externalizing behaviors) when children were 5 years old. Fathers’ ethnic background was a significant moderator for the hypothesized model. Overall, the current study provides substantive evidence for the cascade effects of fathers’ developmental experiences on their individual functioning, intimate relationships, father-child relationships, and children’s development.

Keywords: Intergenerational Fathering, Relationship Quality, African American Fathers

Introduction

Empirical evidence has demonstrated that fathers play an integral role in promoting the optimal development (e.g. social, emotional, and academic) of their children [1-3]. Fatherhood scholars are not only invested in understanding the child-related implications of various fathering practices, but investigators are acutely focused on understanding the determinants and antecedents of father involvement [4-6]. A natural outcome of this line of inquiry has been examining the effects of childrearing experiences on the individual functioning of fathers and their ability to be involved with their children. Initially, the research examining the intergenerational transmission of parenting practices (i.e. father involvement) was primarily focused on understanding how harsh/abusive fathering practices are transferred from one generation to the next, which was a direct byproduct of this work being grounded in the etiology of child abuse [4]. However, current research is expanding its scope to cover the intergenerational transmission of the practice of fathers being involved with their children in ways that positively support child development [7,8]. Overall, the rationale for examining childrearing experiences of contemporary fathers is to determine mechanisms of intergenerational transmission, historical factors that may promote healthy father-child relationships, and effective interventions for fathers with problematic developmental histories, which may help to prevent cycles of abuse. It is assumed that achieving these research goals may assist in promoting positive father-child interactions and optimal socio-emotional development of children [9].

Understanding family of origin characteristics is instrumental for gaining comprehensive insight on salient contextual factors that may influence father involvement. Like any other phenomenon in family studies, context has strong implications for potential outcomes. However, it appears that fatherhood may be more strongly influenced by context than motherhood due to its undefined role prescriptions [10,11]. For example, the Fathering Vulnerability Hypothesis posits that fathers are more vulnerable to intimate relationship difficulties than mothers, and this difference may prove to have more adverse effects on child outcomes [11]. Therefore, understanding the context of fathering is as equally important as understanding the individual characteristics of fathers [12].

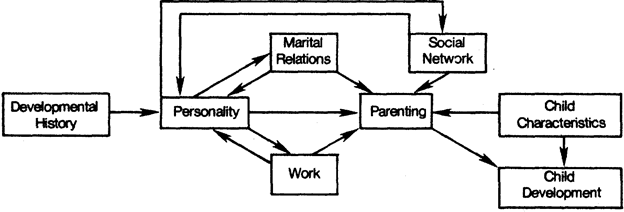

The current study incorporates the developmental history of fathers (e.g. their experiences with their own fathers) into a larger/ comprehensive framework of the various factors that affect father involvement. This framework stems from Belsky’s [4] process model for the determinants of parenting, which lays a solid foundation for understanding the complexity and multidimensional nature of factors that influence parenting. According to Belsky’s [4] process model (see Figure 1), father involvement is multiply influenced by the following domains: personality/psychological well-being of the parent, developmental history of the parent (e.g. childhood experiences with parents), individual characteristics of the children, and the broader social context (e.g. marital relationship, support networks, and work experiences). The current study will focus on the following aspects of Belsky’s [4] model: fathers’ developmental histories (experiences with their own fathers), psychological well being (depressive symptomatology), and intimate/marital relationship quality. We hypothesize that fathers who reported having a high quality relationship with their own biological father and exhibited fewer depressive symptoms at the time of their child’s birth will have a positive influence on their child’s behaviors. A growing body of research supports the intergenerational transmission of mental health concerns and their impact on children’s externalizing behaviors [13]. Specifically, both direct and indirect mechanisms contribute to a child’s developmental outcomes. For example, a father’s temperament and parenting practices may be shaped by his own father’s attitudes and behaviors, which in turn influence his child’s behavioral patterns [14].

Figure 1. Belsky’s [4] process model of the determinants of parenting (p, 84).

Data from the Future of Families and Child Wellbeing study will be utilized for analyses, and one of the notable strengths of utilizing this data is its longitudinal design, which enables the examination of potential causal mechanisms.

Current Study

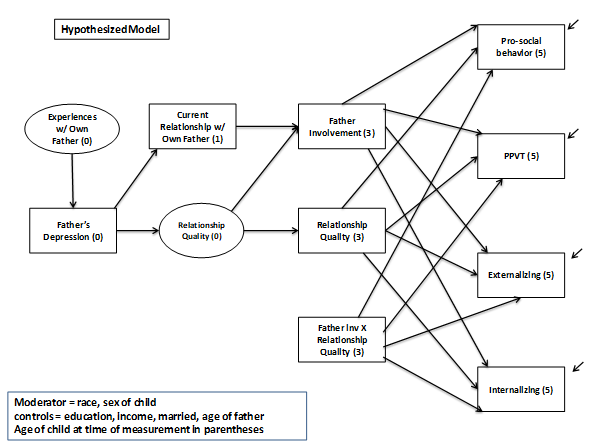

The hypothesized model for the current study (Figure 2) is an adapted version of Belsky’s [4] process model for parenting, in which we examined how fathers’ developmental history with their own biological fathers (level of paternal involvement during childhood), current father-son relationship quality, psychological well-being (depression), and intimate relationship quality affect father involvement and intimate relationship quality. In turn, we examined the indirect effects of these relationships on child outcomes (language skills, pro-social, internalizing, and externalizing behaviors) via father involvement. Due to the differential influences ethnicity on father involvement that have been found in the literature [15-18], race served as a moderator for the current study. Data from the Future of Families and Child Wellbeing study was utilized to examine the long-term effects important contextual factors – relationship quality and paternal depression – experienced postpartum (when fathers’ children were born) on father involvement at age three and children’s language skills (PPVT scores), pro-social, internalizing, and externalizing behavior at age five. Furthermore, intergenerational fathering was examined in this framework to provide a possible historical explanation for contemporary fathering practices.

The current study expands the literature on intergenerational fathering in the following key ways: 1) both retrospective and current accounts of participants’ experiences/relationship quality with their father were included; 2) a strengths-based approach was utilized, in that, the focus is not on poor parenting but general paternal involvement, and positive child outcomes were included; 3) child outcomes for children in the third generation are examined well beyond infancy (5 years-old); and 4) it provides a more comprehensive framework for a longitudinal examination of intergenerational fathering on child outcomes by investigating this occurrence in the context of paternal psychological well-being (depression) and intimate relationship quality.

Method

Data and Sample

Data were gathered from the Future of Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS), an ongoing, nationally representative, longitudinal study of a birth cohort of 4,898 families that began in 1998. At the time of birth of the focal child, families were recruited from 75 hospitals in 20 cities throughout the United States with a population of at least 200,000 persons [19]. FFCWS is particularly focused on understanding the capabilities of unmarried fathers, relationship dynamics of unmarried parents, child outcomes in vulnerable families, and the influence of public policy and environmental structures on familial and child outcomes. Due to the aforementioned focus of FFCWS, these data prove to provide an optimal sample for the current investigation.

The inclusion criterion for the current analytic sample was ethnic background, and only African American or European American fathers were included to more readily facilitate ethnic comparisons. Due to the high degree of cultural diversity in individuals of Latin American descent, these individuals were excluded from ethnic comparisons made in the current study to prevent over-generalization. The analytic sample (N =3,301) consists of 2,407 African American fathers (73%) and 894 European American fathers (27%).

Measures

Predictor Variables

Childhood Experiences with Biological Father was a latent variable composed of three items. No question directly asking if the respondent lived with his biological father during childhood exists in the data; therefore, the following question will be used as the proxy: “Were you living with both of your biological parents at age 15?” Secondly, the level of paternal involvement received during childhood was assessed at baseline (child’s age 0) by the following question: “How involved in raising you was your biological father?” This item was on a 4-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating very involved and 4 indicating no involvement. Scores were reverse coded so that 4 indicated being very involved and 1 indicated no involvement. Thirdly, when the focal child was 12 months old, fathers were asked whether or not he knew his father during childhood. No measures examining retrospective accounts of father-child relationship quality were available in the data set.

Current Relationship Quality with Biological Father was an observed variable assessed when the child was 12 months old, which asked the following question: “How well do you get along with your father now?” This item was on a 3-point Likert scale with 1 indicating very well and 3 indicating not very well. Scores were reversed coded in order for higher scores to reflect higher levels of relationship quality.

Paternal Depression was assessed at baseline when the focal child was a newborn by a shortened version of Center for Epidemiological Studies’ Depression Scale (CES-D) [20], which included 12 items examining paternal depressive symptoms. Fathers were asked the frequency at which they experienced depressive symptoms within the week prior to the interview. Sample items were the following: “In the past week, how often did you feel depressed? In the past week, how often did you feel everything was an effort? In the past week, how often did you sleep restlessly?” Responses ranged from 0 to 7, with 0 indicating 0 times per week and 7 indicating experiencing the depressive symptom 7 days during the past week. The average scale score was utilized. Furthermore, the Cronbach’s alpha for all of the items was .85.

Intervening Variables

Father Involvement was assessed when the focal child was 3 years old by a composite variable composed of 13 items. Fathers reported the amount of days per week that they participated in the following with the focal child: sings songs or nursery rhymes; hugs or shows physical affection; tells child that he loves him/her; lets child help with simple chores; plays imaginary games; reads stories; tells stories; plays inside with toys; tells child he appreciates something he/she did; takes child to visit relatives; takes child to a restaurant; assists child with eating; and puts child to bed. Possible responses ranged from 0 to 7 days per week. Principal components factor analysis revealed that all items could be represented by one factor, and the Cronbach’s alpha (α = .75) demonstrated an acceptable reliability. Higher scores reflected higher levels of paternal involvement, and lower scores reflect lower levels of father involvement.

Intimate Relationship Quality was assessed at baseline when the child was a newborn by a latent variable composed of five items. Furthermore, intimate relationship quality was also assessed when the child was three years old by a composited variable containing 5 items similar to the items used to assess intimate relationship quality when the child was a newborn. For both the latent variable and composited variable, fathers reported the frequency by which the birth mother was a) “fair and willing to compromise when you have a disagreement;” b) “hits or slaps you when she is angry” (reverse coded); c) “expresses affection or love for you;” d) “insults or criticizes you or your ideas” (reverse coded); and e) “encourages or helps you to do things that are important to you.” All items were on a 3-point Likert scale, and possible responses were 1 (never), 2 (sometimes), and 3 (often). The Cronbach’s alpha (α = .62) for the composite variable for intimate relationship quality (when the child was three years old) was less than ideal. Higher scores reflected a higher level of intimate relationship quality, and lower scores demonstrated lower levels of intimate relationship quality.

Outcome Variables

Pro-social behaviors when the focal child was age 5 were assessed by items from the Adaptive Social Behavior Inventory (ASBI) [21] and the Social Skills Rating Scale (SSRS) [22]. Sample items were: “is sympathetic toward other children’s distress, tries to comfort others when they are upset; will join group of children playing; and understands others’ feelings, like when they are happy/sad/mad.” Possible responses were 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), and 2 (very true or often true). An average score was created for all 12 items measuring pro-social behaviors, and the Cronbach’s alpha (α = .78) was acceptable.

Vocabulary Skills were assessed at child age 5 by the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) Revised [23]. The focal child completed this test during a home visit in which they were administered the PPVT. This procedure involved a research assistant presenting a series of pictures to the child, and there were four pictures on a page in which each picture was numbered [24]. Scores were determined by obtaining a basal set of items (the lowest set of 12 items in which the child had fewer than two mistakes); and obtaining a ceiling set (the first difficult set of 12 items in which the child had 8 or more mistakes, consecutively) [25]. The total raw score was calculated by taking the item number for the last item in the difficult set and subtracting it from the total number of mistakes in all of the sets [25]. Raw scores were utilized for the current study.

Internalizing behaviors – at child age 5, mothers’ report of children’s internalizing behaviors was assessed by the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [26]. Primary caregivers were asked whether or not the focal child displayed certain internalizing behaviors. Sample items are the following: worries, cries a lot, complains of loneliness, feels too guilty, and refuses to talk. Possible responses were 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), and 2 (very true or often true). An average score was created for all 17 items measuring internalizing behaviors, and Cronbach’s alpha (α = .71) was acceptable.

Externalizing behaviors were also assessed at child age 5 by mothers’ report of children’s externalizing behaviors, and the CBCL [26] was utilized. Primary caregivers were asked whether or not it was true that the focal child displayed certain externalizing behaviors. Sample items include the following: argues a lot, gets in many fights, has temper tantrums or hot temper, screams a lot, and teases a lot. Possible responses were 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), and 2 (very true or often true). An average score was created for all of the 24 items measuring externalizing behaviors. Cronbach’s alpha (α = .79) was acceptable.

Moderating and Control Variables

Race was assessed by one dummy variable – one indicating being African American and zero indicating being European American. Child Sex was dummy-coded with 1 indicating a male focal child and 0 indicating a female focal child. Furthermore, Marital Status was also a dummy variable (1=married; 0=not married). Paternal Age was a continuous variable reflecting fathers’ age in years. Paternal Education was assessed by a 9-point Likert scale indicating the highest education completed. Household income was assessed by a 9-point Likert scale indicating the total household income reported by the father.

Analytic Strategy

The first step of analysis included examining the univariate and bivariate statistics for the variables of interest. Secondly structural equation modeling was be used to test the hypothesized model in Figure 1. Additionally, a multiple group analysis was conducted to compare the hypothesized model across African American and European American fathers. These analyses were conducted with Mplus [27]. Lastly, missing data were not imputed; rather, available data from all 843 families were used in analyses by using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation with robust standard errors. FIML estimation is one of the best methods for dealing with missing data [28]. Model fit was assessed by a χ2 statistic/degrees of freedom ratio less than 5 and a RMSEA less than .10 [29].

Results

Descriptive Statistics

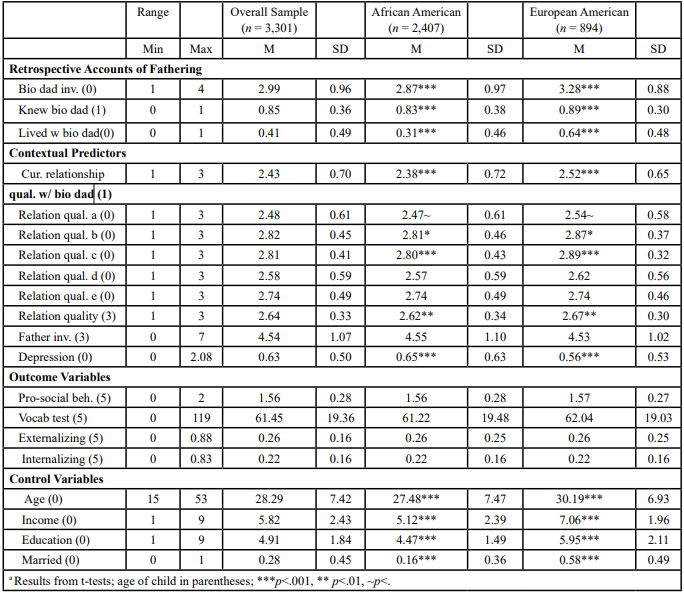

Univariate statistics for each variable in the current study are presented in Table 1a. Furthermore, t-tests were conducted to determine if the means for the variables were significantly different for European American in comparison to African American fathers.

Table 1: Study variables means, standard deviations in the whole sample (N = 3,301) and in the sub-samples of African American (n = 2,407) and European American fathers (n = 894).

Multivariate Analyses

Full Sample

Figure 3 presents the results for the structural equation model that was fit to address the hypothesized model for the entire analytic sample. The model fit statistics indicate that the fit was not ideal (χ2/df =7079.17/164; RMSEA =.11, p = .00; SRMR =.09); therefore, the following results should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, the model fit indices were close to an acceptable range (RMSEA <.10; SRMR <.10), but they were above the standard conventional cutoffs (χ2/df =5; RMSEA <.05; SRMR <.05) [30]. In an examination of the cascade effects, when their children are born, if fathers had poor childhood experiences with their own fathers, they experience depression (β=-.11, p <.001); but, on average, when fathers had more positive experiences with their own biological fathers during their childhood (i.e. living with and knowing their biological father), they experience less depression when their children are born. Furthermore, when their children are born, fathers who are depressed have lower intimate relationship quality with their partners (β=-.12, p <.001). And, when their children are 1, they have lower relationship quality with their own biological fathers (β=-.13, p <.001). Therefore, on average, high levels of paternal depression when their children are born are related to lower levels of relationship quality with respondents’ own fathers (when their children are 1 year old) and intimate partner (when their child is born).

Table 3. Structural equation model of the relations among constructs for childhood experiences with biological father (child age 0), paternal depression (child age 0), current relationship quality with biological father (child age 1), intimate relationship quality (child age 0), intimate relationship quality (child age 3), father involvement (child age 3), pro-social behaviors (child age 5), PPVT (child age 5), internalizing behaviors (child age 5), externalizing behaviors (child age 5), and their related observed variables—full sample (standardized estimated correlations in parentheses) (N=3301). Only significant relationships are shown.

If fathers’ relationship quality with their partners when their children are born is high then their intimate relationship quality with their partners when their children are 3 is also high, and vice versa (β=.56, p <.001). In addition, these fathers have high involvement with their children when they are age 3 (β=.76, p <.001). Therefore, on average, higher levels of intimate relationship quality when children are born are related to higher levels of father involvement and intimate relationship quality when their children are 3, and vice versa. Lastly, only father involvement when children were 3 years old has an effect on child outcomes when children were 5. Namely, high father involvement when children are 3 predicts lower pro-social behavior for their children at age 5 (β=-.02, p =.09), and vice versa. However, this finding should be considered in light of this relationship being fairly minimal and only approaching significance. Overall, all of the predictors in the model, taken together, minimally predicts the variance in children’s PPVT scores (R2= 0.4%) pro-social (R2=1%), internalizing (R2=0.1%), and externalizing (R2= 0.7%) behaviors. However, considerably more variance was explained in relationship quality at child age 3 (R2=24%) by experiences with their own fathers, paternal depression, and intimate relationship quality when their children are born. Five percent of the variation of father involvement at children’s age 3 was predicted by those same variables plus fathers’ current status with their own fathers.

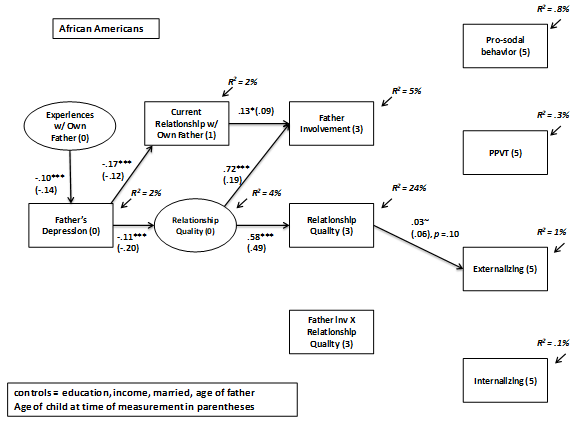

Multiple-group Analysis for Race

To determine if race had a moderating effect on the hypothesized model, a multiple group analysis was conducted, which included two groups: 1) African American fathers and 2) European American fathers (see Figures 4 and 5). Model fit statistics indicate that the fit was not ideal (χ2/df =7921.06/353; RMSEA =.11, p = .00; SRMR = .12). Yet again, these indices were close to an acceptable range (RMSEA <.10; SRMR <.10), but they were above the standard conventional cutoffs (χ2/df =5; RMSEA <.05; SRMR <.05) [30]. In examining differences based on race, if African American fathers experience depression when their children are born, they also experience lower levels of relationship quality with their own fathers when their children are 1 year old (β=-.17, p <.001), and vice versa. However, this finding was not significant for European American fathers. Furthermore, if African American fathers experience higher levels of relationship quality with their own fathers when their children are 1 year old, they also experience higher levels of father involvement with their own children when they are 3 years old (β=.13, p <.05), and vice versa. This relationship was only approaching significance for European Americans fathers (β=.09, p=.06).

Figure 4: Structural equation model of the relations among constructs for childhood experiences with biological father (child age 0), paternal depression (child age 0), current relationship quality with biological father (child age 1), intimate relationship quality (child age 0), intimate relationship quality (child age 3), father involvement (child age 3), pro-social behaviors (child age 5), PPVT (child age 5), internalizing behaviors (child age 5), externalizing behaviors (child age 5), and their related observed variables—European American sample (standardized estimated correlations in parentheses) (N=894). Only significant relationships are displayed.

Figure 5: Structural equation model of the relations among constructs for childhood experiences with biological father (child age 0), paternal depression (child age 0), current relationship quality with biological father (child age 1), intimate relationship quality (child age 0), intimate relationship quality (child age 3), father involvement (child age 3), pro-social behaviors (child age 5), PPVT (child age 5), internalizing behaviors (child age 5), externalizing behaviors (child age 5), and their related observed variables—African American sample (standardized estimated correlations in parentheses) (N=2,407). Only significant relationships are displayed.

In reference to racial differences for the predictors of child outcomes, if European American fathers experience higher levels of intimate relationship quality when their children are 3 years old, their children display lower levels of internalizing behaviors when they are 5 years old (β=-.03, p <.05), and vice versa. This relationship was not significant for African Americans. Therefore, higher levels of fathers’ intimate relationship quality when their children are 3 years old are related to lower levels of children’s internalizing behaviors at age 5 only for European Americans. Interestingly, an interaction of father involvement and relationship quality when the child was 3 only exists for European American fathers; when European American fathers display high levels of father involvement when their children are 3 years old and also experience high levels of intimate relationship quality when their children are 3 years old, their children also experience higher levels of internalizing behaviors when they are 5 years old (β=.007, p =.09). Therefore, when high levels of father involvement are coupled with high levels of intimate relationship quality when children are 3 years old, internalizing behaviors in children at age 5 are also high, and vice versa. This was only true for European Americans. A prototypical plot displaying this relationship is presented in Figures 6 and 7. Lastly, when African Americans fathers experience high levels of intimate relationship quality when their children are 3 years old, their children are more likely to experience externalizing behaviors when they are 5 years old (β=.03, p =.10), and this relationship was approaching significance for African Americans but was not significant for European Americans. Therefore, for African Americans, higher levels of intimate relationship when their children are 3 years old are related to higher levels of children’s externalizing behaviors when they are 5 years old. Furthermore, more variance was explained in the child outcomes and predictors for European Americans in comparison to African Americans. For example, 32% of the variance in intimate relationship quality when children were 3 years old was explained for European American fathers in comparison to 24% of the variance in intimate relationship quality for African American fathers when their children were 3 years old. Also, the variance in children’s PPVT scores (R2= 4%) pro-social (R2=4%), internalizing (R2=3%), and externalizing (R2= 3%) behaviors for European Americans was slightly higher than what was explained for African Americans. Practically no variation was explained in children’s PPVT scores (R2= .3%) pro-social (R2=.8%), internalizing (R2=1%), and externalizing (R2= .1%) behaviors for African Americans.

Discussion

Empirical support for the vital role of fathers in child development has been unwavering [31-33]. Furthermore, it has been well established that father involvement is embedded within a larger ecological context that is affected by various subsystems and individual characteristics. Therefore, the primary goal of the current study was to examine the malleability of fathering to varying historical, psychological, and relational contexts – namely childhood and current experiences of fathers with their own biological fathers, paternal depression, and intimate relationship quality. Furthermore, the cascade of these effects – originating from childhood experiences with one’s father to the residual effects of these experiences on intimate relationship quality and father involvement – was used to predict child outcomes (pro-social behaviors, PPVT scores, internalizing, and externalizing behaviors). Due to the higher prevalence of African American children living in mother-only homes [34], we wanted to determine if the current model was moderated by race. An important caveat should be considered for the following discussion: the findings for the current study should be interpreted with caution due to the model fit for all of the models being relatively poor. Furthermore, due to the moderating effect of race and child sex, the findings for the full model are only preliminary.

One of the most important findings of the current study was the significant negative relationship between fathers’ past experiences with their own biological fathers on their depressive symptomatology when their children are born. This finding addresses an important gap in the literature on the intergenerational transmission of fathering practices: for few, if any studies, have examined how fathers’ past experiences with their own fathers may have implications for fathers’ psychological distress. This relationship was true regardless of fathers’ ethnic backgrounds or the sex of focal children. Interestingly, this relationship occurs during the transition into parenthood for fathers and the earliest stage of life for children, infancy. Therefore, fathers’ positive experiences with their own biological fathers when they themselves were children may reduce the likelihood of experiencing depression when their children are newborns. Conversely, fathers’ negative childhood experiences with their own fathers may have negative implications for their infants via compromised psychological distress, namely a heightened risk for depression. Based in current research indicating the deleterious effects of paternal depression on warm and sensitive caregiving/ parenting [35-37], it appears that fathers’ positive past experiences with their own fathers during childhood may foster an emotional climate that is ideal for warm and sensitive parenting when children are newborns – a developmental period for children that needs high quality/warm caregiving. The reverse would also be true, such that fathers’ negative childhood experiences with their biological fathers may compromise their mental health when their children are born, which may not serve as a conducive emotional environment for warm and sensitive parenting.

In reference to the moderating effect of race, differences were observed between European and African American fathers, and two of the most notable differences observed for the predictors were for the effects of fathers’ depression when their children are newborns and current relationship quality with one’s biological father when their children are 1 year old. For example, when African American fathers experience higher levels of depression after the birth of their children, they also report lower levels of relationship quality with their biological fathers when their children are 1 year old, and vice versa. However, this relationship was not significant for European Americans. Furthermore, African American fathers’ relationship quality with their biological fathers when their children are 1 year old is positively related to their levels of father involvement when their children are 3 years old, such that higher levels of African American fathers’ relationship quality with their biological fathers when their children are 1 year old is related to higher levels of father involvement when their children are 3 years old. These findings suggest that African American fathers’ relationship with their own fathers when their children are 1 year old may be more heavily influenced by psychological distress experienced when their children are newborns, and this sensitivity doesn’t appear to exist for European American fathers. In general, African American fathers experience higher symptoms of depression than other racial groups when navigating stressors attributed to manhood/fatherhood. Moreover, African American fathers in the United States are exposed to socio-environmental factors that exacerbate psychological distress such discrimination, social and economic marginalization, systemic incarceration, and police violence [13].

In addition,African Americans’ father involvement at child age 3 was positively related to their relationship quality with their own fathers at child age 1, but this relationship was only approaching significance for European Americans. Extrapolating from these findings, it may be plausible that African American fathers are more vulnerable to the effects of depression on their current relationship quality with their own fathers due to their higher incidence of experiencing depression. Furthermore, due to the higher incidence of mother-only homes African American children [34], it is reasonable to conclude that having a positive relationship with one’s biological father would be especially important for African American fathers’ involvement with their children. This assumption is supported by findings from the Shannon et al. [6] study, which utilized a racially diverse sample of inner-city fathers, and 42% were African American. They found that paternal acceptance received during childhood was positively related to responsive-didactic interactions with infants, for the fathers in their sample. However, they did not test if race had a moderating effect on their model. In the United States, research consistently indicates that African American men, on average, spend more time with their children compared to other racial groups of fathers who are also unwed and co-parenting [38-40]. This pattern suggests that despite structural barriers, including economic disparities, systemic discrimination, and high rates of nonmarital births within the African American community, many Black fathers remain actively engaged in their children’s lives, which may explain why father involvement is statistically significant for African American fathers but not for their European American counterparts.

Taken together, these findings address an important gap in the literature, for few, if any, studies have examined how race may moderate the effects of paternal depression on fathers’ relationships with their own biological fathers, or the moderating effect of race on the relationship between fathers’ current relationship with their own biological fathers and how this affects their involvement with their children.

With regard to the moderating effect of race on child outcomes, intimate relationship quality when children are 3 years old is negatively related to internalizing behaviors in children at age 5; however, this relationship was only significant for European Americans. This finding corresponds with previous research that has examined the effects of marital conflict and inter-parental relationship violence on children’s internalizing behaviors, which has demonstrated that marital conflict and relationship violence increase the likelihood of internalizing behaviors in children [41-43].

The benefit of the current study was that we were examining the opposite end of the relationship quality continuum by examining intimate relationship quality instead of intimate relationship conflict, which is a construct that has been primarily examined in its relation to children’s internalizing behaviors.Interestingly, the effect of intimate relationship quality at child age 3 was positively related to externalizing behaviors in children at age 3 for African Americans (this relationship was approaching significance). This finding in is in stark contrast to previous research that has found that intimate relationship quality is negatively related to externalizing behaviors in children [44]. One possible explanation for this finding is cultural differences in family dynamics. European American families may place greater emphasis on the nuclear family structure, making the quality of intimate relationships between parents more central to children’s emotional well-being. In contrast, African American families often have strong extended family networks and communal child-rearing practices that provide additional emotional and practical support [13,45]. These supportive structures may help buffer children from the effects of parental relationship quality, fostering resilience and emotional well-being.

Lastly, the interaction between father involvement at child age 3 and intimate relationship quality at child age 3 is positively related to internalizing behaviors in children when they are 5 years old for European Americans (this relationship is approaching significance), and this relationship is not significant for African Americans. Therefore, when intimate relationship quality (at child age 3) is also considered in the context of the father involvement (at child age 3), the combination of their effects is positively related to internalizing behaviors when their children are 5 years old. This finding is rather surprising in light of the current study demonstrating a negative relationship between intimate relationship quality and internalizing behaviors for European Americans. It could be possible that higher levels of father involvement are related to higher levels of internalizing behaviors regardless of experiencing higher levels of intimate relationship quality due to the ways in which men are socialized to avoid the expression of vulnerable feelings [46]. This socialization may increase the likelihood of internalizing behaviors in European American children when their fathers are highly involved in their lives. Additionally, another explanation may be related to the spillover hypothesis, which posits that emotional dynamics between parents can influence parent-child interactions [47]. If father involvement is occurring in a context where the intimate relationship quality is high but also characterized by emotional regulation styles that discourage open emotional expression, children may internalize stress or tension rather than externalizing it. Research has indicated that parental warmth and emotional availability play a crucial role in buffering against internalizing behaviors, and when fathers are highly involved but less emotionally expressive, children may struggle with internalizing symptoms [48].

An important limitation of the current study was the fit of the structural equation model, which may be due to missing data. Gathering longitudinal over several years is characteristically challenging, and it is especially difficult to gather longitudinal data from fathers.

Overall, the current study adds to the literature by demonstrating intergenerational effects of fathering on child outcomes – specifically children’s pro-social, internalizing, and externalizing behaviors. It appears that past experiences with one’s father may have implications for adult psychological distress, and in this case, paternal depression. Furthermore, paternal depression negatively affects fathers’ current relationship quality with their own fathers, but this appears to only be true for African American fathers. In addition, fathers’ current relationship quality with their own fathers has positive bearings on their levels of father involvement. The most robust finding was observed for the positive effects of intimate relationship quality when children are newborns on father involvement when children are 3 years old. Therefore, intimate relationship quality experienced after the birth of a child has implications for father involvement during toddlerhood. This finding corroborates a wealth of previous research demonstrating positive spillover effects for high quality intimate relationship functioning on father involvement [49-52].

In reference to the child outcomes examined in the current study, we did not predict children’s PPVT scores in any of the models – indicating that father involvement, intimate relationship quality, and the interaction between father involvement and intimate relationship quality at age 3 are not significantly related to children’s vocabulary skills when they are 5 years old. This finding contrasts with previous research findings that have found a positive relationship between father involvement and children’s academic/cognitive outcomes [53,54]. Race proved to serve as a moderator for the current study. Overall, this study provides empirical evidence that supports the process model for parenting proposed by Belsky [4] and is a promising step toward gaining a more comprehensive understanding of how intergenerational, psychological, and relational contexts influence fathering, and in turn, how the cascade of these effects on fathering has implications for children’s pro-social, internalizing, and externalizing behaviors.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Cabrera, N. J., (2020). Father involvement, father-child relationship, and attachment in the early years. Attachment & human development, 22(1), 134-138. View

Cano, T., Perales, F., & Baxter, J. (2019). A matter of time: Father involvement and child cognitive outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81(1), 164-184. View

Toldson, L A. (2008). Breaking barriers: Plotting the path to academic success for school-age African-American males. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, Inc.View

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55, 83-96.View

Weiss, C.C., & Furstenberg, F.F. (2000). Intergenerational transmission of fathering roles in at risk families. Marriage and Family Review, 29, 181-201. View

Shannon, J.D., Tamis-LeMonda, C.S., & Margolin, A. (2005). Father involvement in infancy: Influences of past and current relationships. Infancy, 8, 21-41. View

Jessee, V., & Adamsons, K., (2018).Father Involvement and Father–Child Relationship Quality: An Intergenerational Perspective. Parent Sci Pract; 18(1):28-44. View

Schofield, T. J., Conger, R. D., & Neppl, T. K. (2014). Positive parenting, beliefs about parental efficacy, and active coping: three sources of intergenerational resilience. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(6), 973. View

Chen, Z., & Kaplan, H. B. (2001). Intergenerational transmission of constructive parenting. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 17-31.View

Doherty, W.J., Kouneski, E.F., & Erickson, M.F. (1998). Responsible fathering: An overview and conceptual framework. Journal of Marriage and Family, 60, 277-292. View

Goeke-Morey, M. C., & Cummings, E. (2007). Impact of father involvement: A closer look at indirect effects models involving marriage and child adjustment. Applied Developmental Science, 11, 221-225. View

Levy-Shiff, R., & Israelashvili, R. (1988). Antecedents of fathering: Some further exploration. Developmental Psychology, 24, 434-440. View

Parchment, T. M., Saran, I., & Piñeros-Leaño, M. (2023). An intergenerational examination of retrospective and current depression patterns among Black families. Journal of Affective Disorders, 338, 60–68. View

Hancock, K.J., Mitrou, F., Shipley, M. et al. (2013). A three generation study of the mental health relationships between grandparents, parents and children. BMC Psychiatry 13, 299. View

Coley, R. L., & Chase-Lansdale, P. L. (1999). Stability and change in paternal involvement among urban African American fathers. Journal of Family Psychology, 13, 1-20. View

Coley, R. L., & Hernandez, D. C. (2006). Predictors of paternal involvement for resident and nonresident low-income fathers. Journal of Developmental Psychology, 42, 10411056. View

Cooksey, E. C., & Fondell, M. M. (1996). Spending time with his kids: Effects of family structure on fathers’ and children’s lives. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 693707. View

Leavell, A., Tamis-LeMonda, C., Ruble, D., Zosuls, K., & Cabrera, N. (2012). African American, white and Latino fathers' activities with their sons and daughters in early childhood. Sex Roles, 66, 53-65. View

Reichman, N., Teitler, J., Garfinkel, I., & McLanahan, S. (2001). Fragile families: Sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review, 23, 303–326. View

Ross, C.E., & Mirowsky, J. (1984). Components of depressed mood in married men and women: The center for epidemiologic studies' depression scale." American Journal of Epidemiology, 119, 997-1004. View

Hogan, A.E., Scott, K.G., & Bauer, C.R. (1992). The Adaptive Social Behavior Inventory (ASBI): A new assessment of social competence in high-risk five-year-olds. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 10, 230-239. View

Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (2007). Social Skills Rating System. Toronto: Pearson Publishing. View

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, L. M. (1997). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, (3rd Ed.). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. View

Bendheim-Thoman Center for Research on Child Wellbeing. (2011). Scales Documentation and Question Sources for the Nine-Year Wave of the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study. View

Traxel, N., & Bo, Z. (2008). Variance among interviewers in data for the Peabody picture vocabulary test-IIIA. Psychological Reports, 103, 643-651. View

Achenbach, T. M. (1992). Manual for the child behavior checklist / 2-3 and 1992 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry. View

Muthén, L.K. & Muthén, B.O. (1998-2010). Mplus User’s Guide. Fifth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. View

Acock, A. C., (2005). Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 1012 - 1028. View

Wheaton, B., Muthen, B., Alwin, D., & Summers, G. (1977). Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. In D.Heise (Ed.). Sociological methodology (pp. 84-136). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. View

Kline, R.B. (Ed.). (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. View

Marsiglio, W., Amato, P., Day, R. D., & Lamb, M. E. (2000). Scholarship on fatherhood in the 1990s and beyond. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1173-1191. View

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(5), 603–619. View

Pleck, P. H., & Masciadrelli, B. P. (2004). Paternal involvement by residential fathers: Levels, sources, and consequences. In Lamb, M. E. (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (pp. 1-31). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. View

U.S. Bureau of the Census (2023). Parent/child family groups with children under 18. View

Davis, R., Davis, M.M., Freed, G.L., & Clark, S.J. (2011). Fathers’ depression related to positive and negative parenting behaviors with 1-year-old children. Pediatrics, 127, 612-618. View

Jacob, J., & Johnson, S.L. (1997). Parent-child interaction among depressed father and mothers: Impact on child functioning. Journal of Family Psychology, 11, 391-409. View

Wilson, S., & Durbin, C. (2010). Effects of paternal depression on fathers' parenting behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 167-180. View

Ellerbe, C. Z., Jones, J. B., & Carlson, M. J. (2018). Race/ Ethnic Differences in Nonresident Fathers’ Involvement after a Nonmarital Birth. Social Science Quarterly, 99(3), 1158–1182. View

Edin, K., Tach, L., & Mincy, R. (2009). Claiming Fatherhood: Race and the Dynamics of Paternal Involvement among Unmarried Men. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 621(1), 149177. View

Johnson, M. S., & Young, A. A. (2016). DIVERSITY AND MEANING IN THE STUDY OF BLACK FATHERHOOD: Toward a New Paradigm. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 13(1), 5–23. View

Camacho, K., Ehrensaft, M. K., & Cohen, P. (2012). Exposure to intimate partner violence, peer relations, and risk for internalizing behaviors: A prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, 125-141. View

Cummings, E., & Davies, P. T. (1994). Maternal depression and child development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 35, 73-112. View

Emery, C. R. (2011). Controlling for selection effects in the relationship between child behavior problems and exposure to intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26, 1541-1558. View

Ackerman, B. P., D'Eramo, K., Umylny, L., Schultz, D., & Izard, C. E. (2001). Family structure and the externalizing behavior of children from economically disadvantaged families. Journal of Family Psychology, 15, 288-300. View

Mollborn, S., Fomby, P. & Dennis, J.A., (2011). Who Matters for Children’s Early Development? Race/Ethnicity and Extended Household Structures in the United States. Child Ind Res 4, 389–411. View

Watts Jr., R. H., & Borders, L. (2005). Boys' perceptions of the male role: Understanding gender role conflict in adolescent Males. Journal of Men's Studies, 13, 267-280. View

Sears, M. S., Repetti, R. L., Reynolds, B. M., Robles, T. F., & Krull, J. L. (2016). Spillover in the Home: The Effects of Family Conflict on Parents’ Behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(1), 127–141. View

Baker, A. J., & Verrocchio, M. C. (2016). Parental bonding and parental alienation as correlates of psychological maltreatment in adults in intact and non-intact families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(12), 3750-3762. View

Carlson, M. J., Pilkauskas, N. V., McLanahan, S. S., & Brooks Gunn, J. (2011). Couples as partners and parents over children's early years. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73, 317-334. View

Cummings, E. M., Goeke-Morey, M. C., & Raymond, J. (2004). Fathers in family context: Effects of marital quality and marital conflict. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (4th ed., pp. 196–221). Hoboken,NJ: Wiley. View

Feldman, S. S., Nash, S. C, & Aschenbrenner, S. (1983). Antecedents of fathering. Child Development, 54, 1628-1636. View

Volling, B., & Belsky, J. (1991). Multiple determinants of father involvement during infancy in dual earner and single-earner families. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 461-474. View

Flouri, E., & Buchanan, A. (2004). Early father's and mother's involvement and child's later educational outcomes. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 141-153. View

Seokhee, C., & Campbell, J. (2011). Differential influences of family processes for scientifically talented individuals' academic achievement along developmental stages. Roeper Review, 33, 33-45. View