Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour Volume 7 (2025), Article ID: JMHSB-197

https://doi.org/10.33790/jmhsb1100197Research Article

Ten Years Later: What Have We Learned from Implementing the WHO Designed Problem Management Plus Globally? A Scoping Review of Barriers and Lessons Learned

Shahnaz Savani1*, Leslie Sirrianni2, Andrea Germany3, and RoseAnne M. Droesch4

1Assistant Professor, Montgomery County Community College, 101 College Drive, Pottstown, PA 19464, United States.

2Director of Field Education, University of Houston-Downtown, 1 Main Street, Houston, Texas 77002, United States.

3Assistant Professor of Practice, The University of Texas at Arlington, Box 19129, 501 W Mitchell Street, Arlington, TX 76019-0129, United States.

4Clinical Assistant Faculty, Washington State University, 2710 Crimson Way, Richland, WA 99354, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Shahnaz Savani, Assistant Professor, University of Houston-Downtown, 1 Main Street, Houston, Texas 77002, United States.

Received date: 10th January, 2025

Accepted date: 25th March, 2025

Published date: 27th March, 2025

Citation: Savani, S., Sirrianni, L., Germany, A., & Droesch, R. M., (2025). Ten Years Later: What Have We Learned from Implementing the WHO-Designed Problem Management Plus Globally? A Scoping Review of Barriers and Lessons Learned. J Ment Health Soc Behav 7(1):197.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

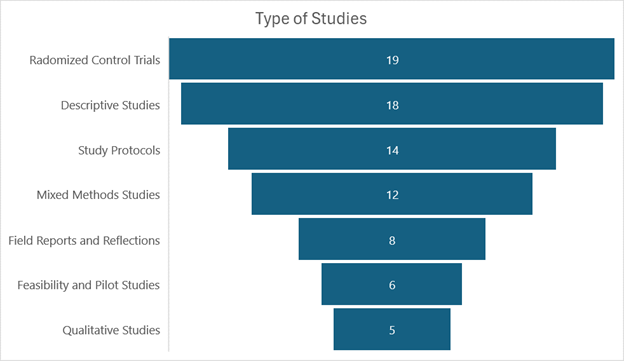

Problem Management Plus (PM+) is a brief transdiagnostic intervention developed by the World Health Organization in 2015 and is intended to be delivered by lay counselors to address the vast mental health treatment gap particularly in low- and middle income countries. Over the last 10 years, PM+ has been implemented across the globe with numerous randomized control trials providing evidence for its efficacy. This scoping review examines the global implementation of PM+, identifying barriers, lessons learned, and key practices for successful deployment across diverse settings. Following PRISMA guidelines, a comprehensive search across five electronic databases (Academic Search Complete, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and SocINDEX) was conducted. Two pairs of authors independently reviewed and selected peer-reviewed articles, with all four reviewers extracting data. Of the 292 studies retrieved, 82 articles met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review. The literature comprised 19 randomized controlled trials, 18 descriptive studies, 14 study protocols, 12 mixed methods studies, eight field reports/reflections, six feasibility/pilot studies, and five qualitative studies. Thirty-one articles addressed implementation barriers, while 30 discussed lessons learned. Using an ecological systems framework, we categorized findings into three levels: individual/ micro (participant and counselor engagement), community/mezzo (training and implementation), and institutional/macro (scaling up PM+ within governmental and political structures). Published research demonstrates the effectiveness of the PM+ intervention in mediating symptoms of common mental health distress. This review synthesizes key implementation barriers and effective strategies for scaling PM+ across settings that can be used by researchers and service providers in future implementation.

Introduction

Despite decades of evidence-based interventions, common mental disorders (CMDs) such as depression and anxiety remain among the leading causes of the global health burden, impacting millions worldwide [1-3]. Globally, 75% - 90% of individuals with a mental health condition remain untreated [4,5]. More than 83% of individuals with mental health conditions reside in low- and middle income countries (LMICs), which are disproportionately affected by humanitarian crises like war, forced displacement, and natural disasters [6]. Heightened stigma [7,8], infrastructure constraints, scarcity of trained mental health professionals, and lack of funding prevent mental health treatments from reaching global communities with the greatest need [9,10].

Common mental disorders respond effectively to evidence based interventions [11-13]. If left untreated, these conditions may become chronic and create significant psychological harm, physical impairment, and an increased risk of suicide [14-16]. Early interventions with front-line treatment strategies like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) have been shown to reduce psychological symptoms of distress and promote overall functioning [17,18].

In 2008, the World Health Organization began to develop and test a series of low-intensity, task shifting interventions as part of its Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) [19]. Task shifting, an approach that moves the delivery of evidence-based interventions from skilled mental health providers to lay counselors [20], has demonstrated promise in LMICs [21-23]. Problem Management Plus (PM+), a brief, transdiagnostic intervention for adults suffering from common mental health problems in low- and middle-income countries, was developed through the mhGAP initiative in 2015 [24]. PM+ targets symptoms of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and grief, as well as addresses practical problems like economic challenges and relationship issues. Four core evidence-based strategies are employed in PM+: a) managing stress, b) managing problems, c) behavior activation, and d) strengthening social support. PM+ is not designed to intervene with suicidal individuals or those suffering from severe mental illness.

For nearly ten years, mounting evidence from RCTs has demonstrated PM+’s positive impact on psychological distress in conflict-affected populations. Schafer and colleagues [25] conducted the first systematic review and meta-analysis on outcomes of PM+ and its digital adaptation, Step-by-Step (SbS). The meta-analysis represented 23 studies (including 5,298 participants) conducted in Pakistan, Lebanon, Kenya, Jordan, The Netherlands, Nepal, Australia, Austria, China, Colombia, Switzerland, Turkey, and the UK. The PM+ intervention was used with populations exposed to war, humanitarian crises, health stressors, and gender-based violence. The study found small to moderate favorable effects across psychological distress indicators and positive mental health outcomes with the largest effects for general distress at both the post-intervention and short-term follow-up assessments. Some researchers have raised concerns about the sustainability of participant gains from PM+, given that outcomes are usually only measured through short-term assessments [26]. The results do indicate the effectiveness of PM+ as a scalable intervention to address common mental disorders and support the well-being of individuals in LMICs. However, the potential for PM+ to have a continual and meaningful impact lies in the effective implementation and scalability of the intervention. To date, there has not been a comprehensive overview of key practices and processes specific to the potential success of implementing PM+ across global settings. Specifically, this study seeks to address the gap in the literature on barriers and lessons learned while implementing the PM+.

The aim of this study is to provide a scoping review of the literature on the applications of the WHO-designed PM+ intervention across various contexts globally. This study also aims to describe the barriers encountered in implementing PM+ and the corresponding lessons learned in addressing these barriers.

Methods

This scoping review was conducted following the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [27]. A literature search was completed by a four-member review team on July 31st, 2024. This review provides an overview of the global use of the WHO designed PM+ and highlights the barriers and lessons learned in its implementation.

Five electronic databases (Academic Search Complete, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and SocINDEX) were searched to identify peer-reviewed articles published after January 1, 2015, and reporting on any aspect of implementation of the WHO developed Problem Management Plus (PM+). The Boolean Search strategy matched the following criteria: Problem Management Plus or PM+ in the title or abstract. Limiters used were peer-reviewed articles in the English language and those published 2015 onwards because the PM+ was developed in 2015. Studies that were systematic or scoping reviews about the PM+ were removed.

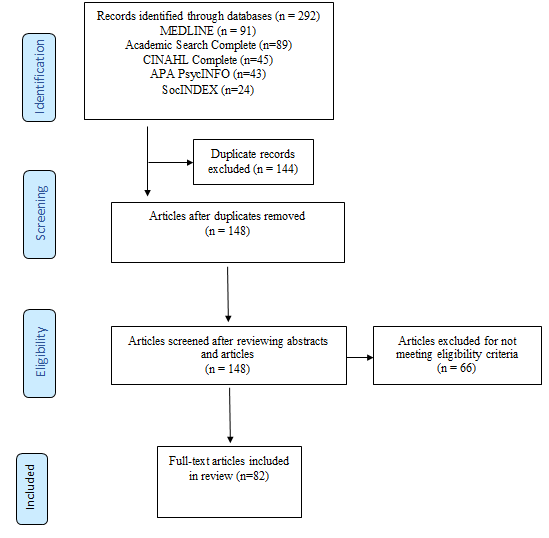

All studies that met the following eligibility criteria were included in the review; published in a peer-reviewed journal, published in the English language, published 2015 onwards, and about the PM+. The search returned 292 records: 91 records from MEDLINE, 89 from Academic Search Complete, 45 from CINAHL Complete, 43 from APA PsycInfo and 24 from SocIndex. These records included 144 duplicates that were removed. A total of 148 remaining articles were entered into an excel sheet for the first phase of review. Please see Figure 1.

All four authors (SS, LS, AG, RD) reviewed 148 abstracts independently for the first phase of review. Articles that focused on any aspect of delivering the PM+ intervention in any format were eligible for the study. Articles that were not specifically about the PM+ were removed. Sixty-six articles were deemed not relevant to our study because they were not about the PM+ or were scoping or systematic reviews. All four authors agreed on the selection of the articles, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Eligible articles included descriptive studies, field reports, reflections, pilot studies, feasibility studies and randomized control trials, mixed methods studies and qualitative studies.

A total of 82 articles were entered into the next phase of review. Two teams of authors (SS and AG; LS and RD) reviewed the full texts of all the 82 articles independently as per eligibility criteria. The review was guided by the following research questions:

1. In which global contexts and among which populations has PM+ been implemented, and what are the key features of its implementations?

2. What types of studies have used PM+, and what specific problems or conditions have been addressed using the PM+?

3. What are the barriers encountered, and the lessons learned in the global implementation of PM+?

Data Abstraction

The articles included in this review were assessed and coded by the research team according to established criteria. Each eligible article was reviewed and coded independently by three teams of two authors each. Coding was completed using a data abstraction form, developed to synthesize findings from all eligible peer-reviewed published studies. The data abstraction form was developed to systematically extract core study components, for example, publication details, study design, sample, study location, target population; focus of intervention; measured outcome, barriers and lessons learned. Barriers to the implementation of PM+ and the lessons learned were identified and categorized into key themes. Using Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems approach [28], these themes were then organized according to those related to the micro system (individual level), mezzo system (community or organizational level), and macro system (societal, governmental or policy-level systems). Discrepancies in coding were resolved through discussion and consensus and used to inform and modify the data abstraction form. Data abstractors maintained over 95% inter-rater reliability across all articles.

Findings

Study Characteristics

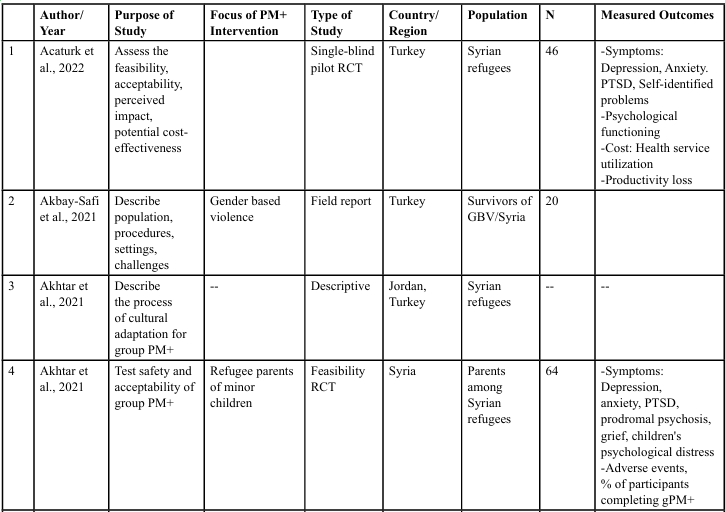

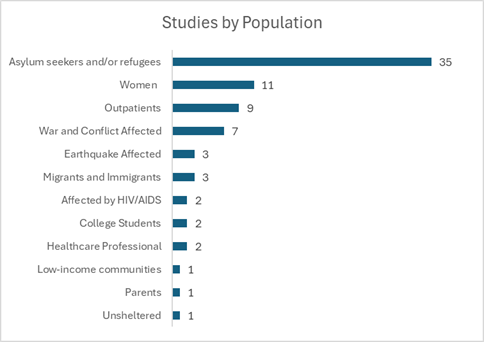

Core study characteristics like the author and year, purpose of study, focus of PM+ intervention, type of study, geographical site of the study, population, sample and measured outcomes were extracted from all the 82 studies reviewed and are presented in Table 1.

Studies by Year

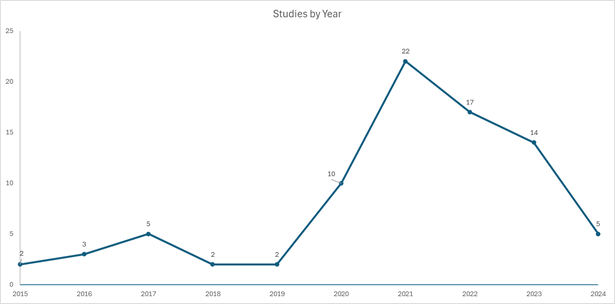

PM+ was introduced in 2015 by the World Health Organization’s mhGAP initiative with the aim of reducing the burden of mental illness and addressing the treatment gap, particularly in low-income settings. Since its inception, PM+ has been implemented across diverse contexts and populations to address a range of mental health conditions globally. Between 2015 and 2019, the number of studies utilizing PM+ was relatively limited. However, following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a substantial increase in research employing PM+ (see Figure 2), which notably incorporated various virtual platforms for delivery and implementation Among the 82 studies published on PM+, 22 were released at the peak of the pandemic in 2021, with 17 published in 2022, and 14 in 2023. (See Figure 2.)

Studies by Location

Seventy-seven studies specified the geographical region in which they were conducted or planned. Most of these studies were conducted in Asia, located in the countries of Afghanistan, China, Iraq, Jordan, Nepal, Pakistan, the Philippines and Syria. Twenty-one studies were conducted in Europe, in the countries of Austria, Italy, France, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine and the United Kingdom. Fifteen studies were based in Africa, covering the Central African Republic, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, Uganda and Zambia. In North America, only four studies were carried out, specifically in the United States and Mexico. In South America, four studies were all based in Colombia. Additionally, one study was conducted in Australia. Eight studies spanned multiple countries, which in addition to the above listed countries included Benen, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Honduras, Lebanon and Peru. (See Figure 3.)

Type of Studies

The majority of studies employing PM+ have been randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The second largest category consists of descriptive studies which outline various aspects of the PM+ intervention. Some elucidate the therapeutic foundations and strategies of PM+, while others document processes related to cultural and linguistic adaptations, training models, delivery mechanisms and implementation practices. Additionally, some studies explore the application of PM+ in higher education contexts and pathways for scaling up the intervention to larger populations. Several studies have focused on outlining protocols for either feasibility trials or fully powered RCTs. A significant number of studies utilize mixed methods, gathering both quantitative and qualitative data from various stakeholders. Fewer studies are field reports or personal reflections detailing experiences related to the delivery, training or implementation of PM+. Specifically, six studies are classified as feasibility or pilot studies, and only five are purely qualitative in nature. (See Figure 4.)

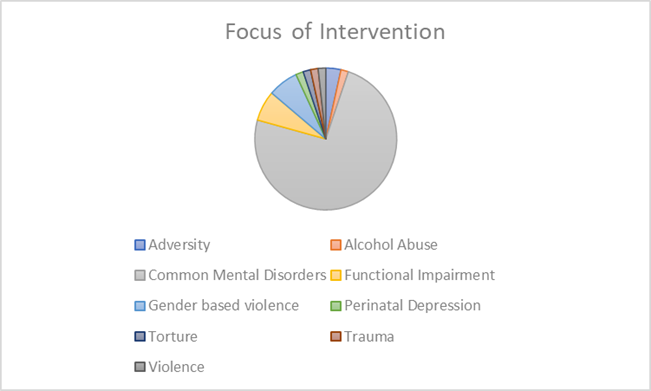

Focus of Intervention

Among the 82 studies reviewed, 66 specified the focus of the PM+ intervention. The majority of these studies (n=52) focused on addressing common mental disorders, including depression, anxiety, trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Five studies specifically targeted issues related to violence in armed conflict or gender-based violence, while an additional five studies addressed general well-being, including functioning, interactions with children in refugee contexts, and challenges related to post-migration adjustment. Furthermore, one study aimed to address adversity, and another focused specifically on perinatal depression. (See Figure 5.)

PM+ Implementation: Barriers and Lessons Learned

An overall examination of the 82 studies included in this scoping review identified 31 studies that discussed barriers and 30 studies that described lessons learned from implementing the PM+ intervention. Using an ecological systems approach [28] the barriers and lessons learned were grouped into the following three categories: (1) Participant and Counselor Engagement (Individual/ Micro) (2) Training and Implementation (Community/Mezzo), and (3) Scaling Up PM+ in Governmental and Political Structures (Institutional/Macro). The following section describes the barriers and corresponding lessons learned in each category. (See Figure 6.)

Participant Engagement

Five articles identified stigma related to mental health needs as a significant barrier in engaging with treatment [29-32]. One participant verbalized the following:

Stigma is still a big issue we are facing in our culture and in between refugees. Because of stigma, most of the people, maybe they didn’t seek any help until they reach big problems […] I think we can increase the awareness in the community, and we will have to keep stigma in our mind; that it is still a problem. But I think in the last 10 years, stigma, as it is, become maybe a little bit not like before, but for example, in the rural areas, it is still big issue [32].

Another barrier noted was the propensity of clients towards a medical model of treatment. Engaging in a psycho-social model of treatment seemed alien to many. One participant noted:

Sometimes our people [Jordanian/Middle Eastern] they do not believe in counselling, therapeutic sessions. They only believe in medication. Like “Give me medication, then I will get improved.” So, we have to change the mentality of our people first [32].

Additionally, participants’ literacy levels, limited understanding of mental health concepts and/or the presence of cultural norms that encourage patience and tolerance often led them to underreport symptoms and overreport levels of improvement upon receiving treatment. Gebrekristos and colleagues noted, “...it was common to underreport symptom severity because to express distress is seen as ‘complaining against God’” [33].

Two studies identified concerns around confidentiality as a barrier for both participants and lay providers: with both groups belonging to close knit communities, participants and providers were wary of their privacy being protected [34,35]. Other cultural norms affected the participation of women in PM+. Among Syrian refugees in Jordan, females needed permission of a male family member to participate in PM+ groups, further limiting their access to treatment [32].

Of the strategies introduced in PM+, participants identified the stress management strategy as the most practiced skill and the problem solving strategy as the most challenging [30,36]. Challenges with the problem-solving strategy included participant difficulty in identifying solvable vs. unsolvable problems, as well as challenges in choosing a single problem to address. Participants also struggled to identify potential solutions to the identified problem. Many participants were focused on prioritizing immediate practical problems, such as the need for adequate housing or employment, over problems related to mental health [29-31,37,38].

Nine studies identified additional barriers faced by participants in accessing PM+. Many clients experienced competing priorities for time due to family responsibilities and work commitments. Often work opportunities arose spontaneously creating challenges in scheduling and rescheduling. Additional barriers included access to transportation and childcare [22,30,33 35,36,39-42].

Several studies addressed lessons learned specific to participant engagement. Integrating PM+ into general health care was believed to increase access and reduce stigma of seeking mental health support [43]. Akhtar and colleagues [44] found that initial engagement in PM+ was key to its acceptance and retention of participants through treatment completion. Completing the first session greatly improved the likelihood of participants remaining engaged through to session five. Intentionality and focus on initial engagement strategies, particularly for men were found to be important in successfully recruiting and retaining participants [45]. Meaningful strategies to increase and retain engagement with PM+ included: (a) better education and messaging around the goals and content of PM+; (b) assurance and consistency in providing confidentiality; (c) paying attention to gender concordance between participants and providers; and (d) engaging family members at different points of the intervention to provide additional support. Further, using key stakeholders for implementation of PM+ and endorsement from community role models was found to play a significant role in encouraging acceptability and participation in the intervention [31,35,37,46]. Goloktionova et al., [47] identified the usefulness of developing a workbook for participants to use. This would increase participant engagement throughout the intervention to reinforce learning between sessions and once sessions conclude.

Counselor Engagement

Much of the PM+ treatment delivery occurs in low resource settings by trained community volunteers. Community helpers, who originate from the same marginalized communities as their clients, often struggle with balancing PM+ training and skill acquisition against other pressing responsibilities. The multiple roles these volunteer workers juggle create substantial barriers to retention and sustained engagement [32,35,48-50]. Four studies identified providing financial compensation and a clear pathway for volunteer workers towards professional job growth as key strategies to increase community volunteer retention [29,32,51,52].

In addition to the increased workload for community volunteer providers, compassion fatigue was another notable concern [51,53]. Providers were at risk of experiencing secondary trauma through delivery of the PM+, and sensitivity to provider mental health was a key feature in the retention of community providers [37,47,54]. The inclusion of trauma-informed care training and practice, directed to both the community volunteers as well as participants, was identified as an important consideration [46].

Several studies identified the importance of establishing selection criteria in choosing volunteers for PM+ [50,55]. Identified criteria could include effective use of language, social skills, and openness and capacity for reflective listening. Lay providers who had prior experience within the helping professions were found to be more successful in engaging in a manualized protocol. However, individuals with minimal experience were also capable of exhibiting crucial helping competencies given adequate training [30,52,55,56]. Both Akhtar et al., [44], and Goloktoionova et al., [47] found that the effectiveness of the providers is closely linked to their personal experience with the intervention. When volunteers can both learn and apply PM+ coping mechanisms themselves, they experience a significant boost in self-efficacy, which enhances their ability to support participants.

Robust training and supervision were noted to be critical in contributing to community provider retention [29,51,52]. Barriers related to supervision included the need for sufficient and ongoing supervision [50] and confidentiality in supervision [35]. McBride and colleagues [52] found that remote training and supervision could be a viable option for those challenged with transportation and scheduling barriers. Offering training and supervision remotely could increase the ability to recruit a more diverse group of community volunteers to serve as PM+ providers.

Training and Implementation

A substantial barrier to the delivery of the PM+ was the length of sessions. Participants noted that sessions were too long, a barrier particularly salient when many clients had to work or care for children and families [34,39,57]. Gerbrekristos et al. [33] identified the inconsistent session length as a significant barrier. Session one required an average of 90 minutes, session two took approximately 100 minutes, and session four approximately 120 minutes. Notably, revising the managing problems strategy (session three) often took more than 30 minutes, depending on the client’s problem. The ambiguity of implementation protocols also emerged as problematic for community health workers.

The methodology of PM+ does not inherently define or recommend how a programme using this intervention could or should be practically implemented and sustainably maintained. In many ways, these are the central questions that could make or break any intervention (regardless of methodology) [47].

In addition to session length, several studies addressed the need for flexibility in the number and modality of PM+ sessions offered based on the individual needs of the participants [30,31 35,38,46,55]. This included exercising flexibility in determining appropriateness of some components of the PM+ training regarding participant situation (i.e., avoiding the “staying well” component due to COVID pandemic lockdown constraints) and augmenting with specific strategies tailored to the needs of the population receiving the intervention. This might include strategies aimed at reducing symptoms specific to post migration distress [58]. Likewise, findings by Bryant and colleagues [59] indicated that providing augmentation strategies following group PM+ may promote sustained benefit across time.

Contextual challenges in implementing PM+ included language differences and the limited effectiveness of standardized assessments across diverse settings [51]. Further, the PM+ content about understanding adversity was challenging. As Dozio et al., [36] report:

...the word “adversity” has no corresponding translation in some languages including Sangho (the language spoken in the Central African Republic). Moreover, in most conflict and post conflict contexts, adversity is an integral part of people’s lives. Therefore, it was very complicated for the team to work around this notion. Participants had difficulty understanding the reflection that was required around adversity and raised concerns to PM+ interventionists for not considering their most pressing problems like hunger or lack of water [36].

A commonly cited lesson learned was the critical role of engaging key stakeholders in the cultural review of PM+ implementation material to ensure the applicability, accessibility, and acceptability for the population being served [36,40,46-48,60]. While cultural adaptation can be a resource-intensive process, ensuring the appropriate cultural adaptation of the PM+ was key to its successful implementation.

An important concern cited in several studies regarding implementing PM+ in low resource contexts was the reduced capacity to address more complex mental health needs that extended beyond the scope of PM+ [40,55]. Since the PM+ intervention is not intended to address more complex mental health issues, severe distress identified during assessment should be considered carefully for inclusion. Clear guidelines need to be established to determine when PM+ is appropriate based on the level of distress [40].

Ten studies highlighted lessons learned related to the training process for effectively delivering PM+ [30,32,33,38 40,46,49,52,61]. Woodward et al., [32] identified the limited access to qualified trainers and supervisors as a significant barrier. Half of these studies emphasized the critical role of supervision in helping counselors maintain a high level of effectiveness in delivering PM+ core components and underscored the importance of providing refresher training throughout the implementation process [30,33,40,49,61]. Key lessons also include the value of post-training assessments in guiding supervisors to support the development of counselor competency [61].

Several studies addressed the use of role-plays in training and the importance of how they are structured. Nemiro et al., 2021, found that providing multiple opportunities for role-plays prior to participant engagement contributes significantly to counselor skill uptake. Additional lessons include focusing role-play activities to address a limited number of skills at one time; adapting role-play scenarios to resonate with participant populations; recruiting role-play actors and raters from those with prior PM+ experience; and seeking feedback from trainees on role-play performances [33,49,61].

Other mezzo-level training and implementation concerns included the need for improved recruitment strategies, such as better education around the goals and content of the intervention to increase participation [51] and the need to develop effective data collection guidance [46]. Musosto et al., [26] raised a particularly salient concern about the sustainability of participant gains from PM+, given that outcomes are usually only measured through short-term assessments.

Scaling Up PM+ in Governmental and Political Structures

The power of lay delivered interventions like the PM+ lies in their potential for scale up and reach. In humanitarian contexts where PM+ is delivered by community volunteers within refugee communities, government regulations regarding the employability of refugees can create enormous confusion and difficulties in recruiting and utilizing volunteers [32,40]. In these contexts, consumer distrust of government entities can further exacerbate participation difficulties [32,37,55]. Systemic barriers such as the complexity of navigating formal health systems and lack of funding were identified, as well as consumer access barriers due to lack of health insurance or prohibitive deductibles [31,32,50].

Demonstrating cost effectiveness of the PM+ program was deemed critical for gaining support from potential funders [32]. However, in the context of humanitarian crises, difficulties in calculating the cost-effectiveness of PM+ were noted to be significant barriers. Outcomes were often “limited to direct healthcare costs and health- related outcomes of the PM+ intervention and not extend [ing] to the wider economic or social value of investing in mental health....” [62].

In areas where the intervention was modified to be delivered via telephone or internet, infrastructure barriers such as lack of cellular service and internet further complicated the modified intervention [39,35,38,63]. Lack of light in the evenings, volatile conditions, and political conflict created additional challenges for both lay workers and participants [36].

Sixteen studies identified lessons learned about integrating PM+ or scaling up PM+ in community settings. Common themes include critical need for key stakeholder engagement and endorsement at the individual and community levels; coordination with existing public health services, community centers and governmental institutions; and the critical role of cultural adaptation and contextualization of PM+ in implementation scale-up [31,32,35,37 40,42,43,46 49,56,5759,60 63-65].

As noted earlier, integrating PM+ into general health services can minimize stigma and barriers in accessing mental health support [43]. However, such an integration requires scaling up the intervention through institutional policy, political and regulatory systems, and broader health systems and budgetary processes. In addition, expansion to serve larger populations, different population groups, and different geographic sites is warranted. Studies on scaling up PM+ demonstrate improved outcomes when PM+ is integrated within a “stepped care” model of delivering healthcare. Stepped care is an approach to delivering mental health care by focusing on providing the least intensive, most effective treatment first and then "stepping up" to more intensive levels of care if necessary [41,59].

Fuhr et al, [41] notes that health and social care systems whose mission is to provide mental health services for vulnerable populations are most effective in supporting the implementation of PM+. To successfully implement PM+, assessing the environmental factors that can help or hinder its success is crucial. This includes examining local and national policies, the organizational and bureaucratic structure of healthcare systems, the resources available within the health sector, and socio-economic and cultural factors. Additionally, it is important to consider specific needs and rights of individuals, ensuring that services are tailored and accessible to those who need them most [41,64].

Discussion

Over the past decade, PM+ has been well-researched, demonstrating acceptability and effectiveness with varied populations globally. The current review of 82 studies addresses a gap in research on implementing Problem Management Plus. Specifically, this study seeks to address the gap in the literature on barriers and lessons learned while implementing PM+. Effective implementation of PM+ necessitates identifying and addressing micro, mezzo, and macro level barriers.

Several barriers found in implementing the PM+ include micro level barriers like participant stigma of mental illness and its treatment, propensity toward a medical model of treatment, concerns around confidentiality, limited understanding of mental health concepts, and prevailing cultural norms that impeded participation in treatment. Cultural and linguistic adaptation is essential for effective delivery in any context. Addressing micro-level barriers requires a significant degree of cultural competence, which plays a crucial role in overcoming issues such as stigma, differing cultural understandings of stress, and gender-related concerns. Other barriers found were related to PM+ strategies; participants struggled to identify solvable problems during treatment because of the overwhelming humanitarian crises surrounding them. Lessons learned involved integrating PM+ into primary healthcare, focusing on initial engagement, paying attention to gender concordance, and involving family members for additional support. Other barriers included struggles faced by lay volunteers in providing PM+ to their communities. These included juggling different responsibilities while acquiring skills and training to deliver PM+, concerns with not being adequately financially compensated, and the risk of experiencing secondary trauma. Lessons learned included finding resources to adequately compensate lay volunteers and providing effective training and supervision.

Mezzo level barriers included the structure and content of PM+ training and delivery. Inconsistent session length, lack of guidance on implementation, inability of PM+ to address more complex mental health challenges and lack of qualified providers were identified as barriers. Among lessons learned were the critical role of supervision, post training sessions, use of role plays for training and skill uptake, improved strategies for lay counsellor recruitment and better education around the goals of PM+. Macro level barriers included complexity of navigating systems of healthcare, infrastructure barriers such lack of electricity and internet, transportation challenges and volatile conditions. Lessons learned included the critical need for stakeholder engagement, coordination with existing public health services and governmental institutions, and the need for cultural and linguistic adaptation of PM+. Identifying key community stakeholders who can support the cultural adaptation process is important.

Sustainability is heavily influenced by mezzo and macro-level factors, including the ability to scale up interventions, political will, healthcare infrastructure, and the availability of resources for training and delivery. Essential elements such as compensation for trainers, social safety nets that address basic needs, and physical safety within conflict zones are critical for success. One significant challenge is the added responsibility placed on existing lay volunteers, who require compensation, support, ongoing training, coaching, stipends, and supervision. It is crucial to treat these volunteers as employees and provide a nurturing environment that fosters their growth. Additionally, PM+ cannot be effectively delivered in isolation; it must be integrated into a broader support system to ensure its sustainability and effectiveness.

Using the theory of change (ToC) planning tool Fuhr et al., [41], identified two essential pathways for scale up: the policy and finance pathway and the health services and community pathway. The policy and finance pathway includes the identification and availability of responsive mental health policies and plans supporting systems of change, identification of initial fund sources, and establishment of a National Resource and Knowledge Centre that has a mandate to provide training to paraprofessionals and master trainers. The health services and community pathway, which is dependent on the policy and finance pathway, includes the identification of the implementing organization(s) that would lead the delivery of the intervention and specifics of strengthening implementation capacity. Brief interventions may be more successful when integrated into a stepped-care model [64].

Lack of basic needs in humanitarian settings remains a significant barrier to the success of PM+. The implementation of PM+ has underscored the critical importance of addressing basic needs such as food, housing, and income before effective mental health interventions can be realized, highlighting the intricate relationship between social determinants of health (SDOH) and mental well being [66]. This theme is prevalent in the challenges participants faced in accessing the problem-solving coping strategy of PM+ due to the complexity and insolvability of the resource constraints they faced, as well as the lack of basic infrastructure (electricity, internet, cell service) within their local communities and is consistent with the broader literature on SDOH and well-being.

For many, PM+ serves as a starting point for enhancing well-being rather than a comprehensive solution for all mental health problems. Findings from this review point to a "floor" of basic needs beneath which PM+ is much less effective. PM+ may have better, and perhaps more sustained results, when delivered with safety net programs. Likewise, there is also a "ceiling" related to psychological needs that PM+ can address. PM+ is not designed to tackle severe mental health disorders or complex psychological issues. While PM+ has shown promise with certain populations, its success is inherently linked to the stabilization of essential needs and should be viewed as part of a broader framework for holistic mental health support. This finding is consistent with a wider call, including by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health, for “a substantial change in how mental health problems are conceptualized and responded to” [37]. Despite the myriad challenges in the implementation of PM+, the intervention has promise in addressing many symptoms of common mental disorders, can be scaled up through the use of lay volunteers and remains a powerful tool in the attempt to close the treatment gap for mental illness. Future research on PM+ should focus on measuring the effectiveness of PM+ when combined with other basic needs services. Additionally, studies on PM+ implementation should continue to provide insights on lessons learned in different cultural, linguistic and socio-economic contexts around the world.

Limitations

This study makes an important contribution to the literature on implementation of the PM+ globally, however, it is not without limitations. The review is constrained by the quality and quantity of data available on PM+ implementation. Only 30 published studies were found that discussed barriers to implementation of PM+; while 31 studies explored lessons learned. Future research needs to focus on implementation science for PM+, developing guidance for adapting the PM+ training and interventions for diverse populations and measuring the sustained effect of the PM+ intervention in the long term.

Conclusion

PM+ is an effective, low resource, scalable treatment for common mental disorders. This study compiles the evidence on the implementation of PM+ across the globe describing implementation barriers and lessons learned. Limited research is available addressing implementation which remains an important challenge in delivering PM+ effectively. This study makes an important contribution to the literature on implementation of the PM+ in the last 10 years.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators (2022). Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet, 9(2), 137–150. View

Ferrari, A. J., Charlson, F. J., Norman, R. E., Patten, S. B., Freedman, G., Murray, C. J. L., Vos, T., & Whiteford, H. A. (2013). Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Medicine, 10(11), e1001547. View

Vigo, D., Thornicroft, G., & Atun, R. (2016). Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 3(2), 171–178. View

Henderson, C., Evans-Lacko, S., & Thornicroft, G. (2013). Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 777–780.View

Thornicroft, G. (2007). Most people with mental illness are not treated. The Lancet, 370(9590), 807–808. View

World Health Organization. (2004). The global burden of disease 2004, vol. 146. Geneva: Update, World Health Organization. View

Kane, J. C., Elafros, M. A., Murray, S. M., Mitchell, E. M. H., Augustinavicius, J., Causevic, S., Chandrashekar, S., du Plessis, E., Jidda, M., Kergoat, M. J., Kisa, R., Kpobi, L. N., Mall, S., Rannard, S., Richter, L., Selohilwe, O., Stackpool-Moore, L., Thurman, T. R., van Wyk, S., & Aderomilehin, O. (2019). A scoping review of health-related stigma outcomes for high- burden diseases in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 17. View

Murphy, J., Qureshi, O., Endale, T., Esponda, G. M., Pathare, S., Eaton, J., De Silva, M. & Ryan, G. (2021). Barriers and drivers to stakeholder engagement in global mental health projects. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 15, 30. View

Nadkarni, A., Hanlon, C., Bhatia, U., Fuhr, D., Ragoni, C., Perocco, S. L., de A., Patel, V., Saggurti, N., & Ganguli, H. C. (June, 2015). The management of adult psychiatric emergencies in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review. The Lancet Psychiatry. View

World Health Organization. (2014). Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP): Scaling up care for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Bisson, J. I., & Olff, M. (2021). Prevention and treatment of PTSD: the current evidence base. European journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1824381. View

Cuijpers, P., Berking, M., Andersson, G., Quigley, L., Kleiboer, A., & Dobson, K. S. (2013). A meta-analysis of cognitive behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 58(7), 376–385. View

World Health Organization. (2023). Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) guideline for mental, neurological and substance use disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization. View

Akinyemi, O., Atilola, O., & Soyannwo, T. (2015). Suicidal ideation: Are refugees more at risk compared to host population? Findings from a preliminary assessment in a refugee community in Nigeria. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 18, 81–85. View

Peconga, E. K. & Hogh Thogersen, M. (2020). Post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety in adult Syrian refugees: What do we know? Scandanavian Journal of Public Health, 48(7), 677-687. View

Vijayakumar, L. & Jotheeswaran, A.T. (2010). Suicide in refugees and asylum seekers. In Dinesh Bhugra, Tom Craig, and Kamaldeep Bhui (eds), Mental Health of Refugees and Asylum Seekers (pp 195-210). Oxford Academic. View

Reynolds, C. F., 3rd, Cuijpers, P., Patel, V., Cohen, A., Dias, A., Chowdhary, N., Okereke, O. I., Dew, M. A., Anderson, S. J., Mazumdar, S., Lotrich, F., & Albert, S. M. (2012). Early intervention to reduce the global health and economic burden of major depression in older adults. Annual Review of Public Health, 33, 123–135. View

Roberts, N. P., Kitchiner, N. J., Kenardy, J., Lewis, C. E., & Bisson, J. I. (2019). Early psychological intervention following recent trauma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1). View

World Health Organization (2008). mhGAP : Mental Health Gap Action Programme: Scaling up care for mental, neurological and substance use disorders. World Health Organization. View

Orkin, A. M., Rao, S., Venugopal, J., Kithulegoda, N., Wegier, P., Ritchie, S. D., VanderBurgh, D., Martiniuk, A., Salamanca Buentello, F., & Upshur, R. (2021). Conceptual framework for task shifting and task sharing: an international Delphi study. Human Resources for Health, 19(1), 61. View

Bolton, P., Lee, C., Haroz, E. E., Murray, L., Dorsey, S., Robinson, C., Ugueto, A. M., & Bass, J. (2014). A transdiagnostic community-based mental health treatment for comorbid disorders: development and outcomes of a randomized controlled trial among Burmese refugees in Thailand. PLoS medicine, 11(11), e1001757. View

Patel, V., Weiss, H. A., Chowdhary, N., Naik, S., Pednekar, S., Chatterjee, S., De Silva, M. J., Bhat, B., Araya, R., King, M., Simon, G., Verdeli, H., & Kirkwood, B. R. (2010). Effectiveness of an intervention led by lay health counsellors for depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care in Goa, India (MANAS): A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England), 376(9758), 2086–2095. View

Rahman, A., Malik, A., Sikander, S., Roberts, C., & Creed, F. (2008). Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 372(9642), 902-909. View

Dawson, K. S., Bryant, R. A., Harper, M., Kuowei Tay, A., Rahman, A., Schafer, A., & van Ommeren, M. (2015). Problem Management Plus (PM+): A WHO transdiagnostic psychological intervention for common mental health problems. World Psychiatry, 14(3), 354–357. View

Schäfer, S. K., Thomas, L. M., Lindner, S., & Lieb, K. (2023). World Health Organization's low-intensity psychosocial interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of Problem Management Plus and Step-by-Step. World Psychiatry: Official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 22(3), 449–462. View

Musotsi, P., Koyiet, P., Khoshaba, N. B., Ali, A. H., Elias, F., Abdulmaleek, M. W., Simiyu, K. & Rosenkranz, E. (2022). Highlighting complementary benefits of problem management plus (PM+) and doing what matters in times of stress (DWM) interventions delivered alongside broader community MHPSS programming in zummar, ninewa governorate of iraq. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 20(2), 139-150. View

Page, M., McKenzie, J., Bossuyt, P., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T., Mulrow, C., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J., Akl, E., Brennan, S., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J., Hrobjartsson, A., Lalu, M., Li, T., Loder, E., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L., Stewart, L., Thomas, J., Tricco, A...Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71 doi:10.1136/bmj.n71 View

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531. View

Spaaij, J., Kiselev, N., Berger, C., Bryant, R. A., Cuijpers, P., de Graaff, A. M., Fuhr, D. C., Hemmo, M., McDaid, D., Moergeli, H., Park, A. L., Pfaltz, M. C., Schick, M., Schnyder, U., Wenger, A., Sijbrandij, M., & Morina, N. (2022). Feasibility and acceptability of Problem Management Plus (PM+) among Syrian refugees and asylum seekers in Switzerland: A mixed method pilot randomized controlled trial. European journal of psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2002027. View

Van't Hof, E., Dawson, K. S., Schafer, A., Chiumento, A., Harper Shehadeh, M., Sijbrandij, M., Bryant, R. A., Anjuri, D., Koyiet, P., Ndogoni, L., Ulate, J., & van Ommeren, M. (2018). A qualitative evaluation of a brief multicomponent intervention provided by lay health workers for women affected by adversity in urban Kenya. Global mental health (Cambridge, England), 5, e6.View

Woodward, A., de Graaff, A., Dieleman, M. Roberts, B., Fuhr, D., Broerse, J, Sijbrandij, M., Cuijpers, P., Ventevogel, P., Gerretsen, B., & Sondorp, E. (2022). Scalability of a task sharing psychological intervention for refugees: A qualitative study in the Netherlands, SSM - Mental Health (2). View

Woodward, A., Sondorp, E., Barry, A., Dieleman, M., Fuhr, D., Broerse, J., Akhtar, A., Awwad, M., Bawaneh, A., Bryant, R., Sijbrabdij, M., Cuijpers, P. & Roberts, B. (2023). Scaling up task-sharing psychological interventions for refugees in Jordan: A qualitative study on the potential barriers and facilitators, Health Policy and Planning (38), 3, 310–320. View

Gebrekristos, F., Eloul, L., & Golden, S. (2021). A field report on the pilot implementation of problem management plus with lay providers in an Eritrean refugee setting in Ethiopia. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 19(1), 101-106. View

Khan, M. N., Hamdani, S. U., Chiumento, A., Dawson, K., Bryant, R. A., Sijbrandij, M., Nazir, H., Akhtar, P., Masood, A., Wang, D., Wang, E., Uddin, I., van Ommeren, M., & Rahman, A. (2019). Evaluating feasibility and acceptability of a group WHO trans-diagnostic intervention for women with common mental disorders in rural Pakistan: A cluster randomised controlled feasibility trial. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 28(1), 77-87.View

Rodriguez-Cuevas, F. G., Valtierra-Gutiérrez, E. S., Roblero Castro, J. L., & Guzmán-Roblero, C. (2021). Living six hours away from mental health specialists: Enabling access to psychosocial mental health services through the implementation of problem management plus delivered by community health workers in rural Chiapas, Mexico. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 19(1), 75-83. View

Dozio, E., Dill, A. S., & Bizouerne, C. (2021). Problem Management Plus adapted for group use to improve mental health in a war-affected population in the Central African Republic. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 19(1), 91-100. View

Perera, C., Aldamman, K., Hansen, M., Haahr-Pedersen, I., Caballero-Bernal, J., Caldas-Castaneda, O. N., Chaparro-Plata, Y., Dinesen, C., Wiedemann, N., & Vallieres, F. (2022). A brief psychological intervention for improving the mental health of Venezuelan migrants and refugees: A mixed-methods study. SSM-Mental Health, 2, 100109. View

Sabry, S., Baron, N., & Galgalo, F. (2021). Problem management plus when you can’t see their eyes: COVID-19 induced telephone counselling. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 19(1), 121-124. View

Acarturk, C., Uygun, E., Ilkkursun, Z., Yurtbakan, T., Kurt, G., Adam-Troian, J., Senay, I., Bryant, R., Cuijpers, P., Kiselev, N., McDaid, D., Morina, N., Nisanci, Z., Park, A.L., Sijbrandij, M., Ventevogel, P., & Fuhr, D. C. (2022). Group problem management plus (PM+) to decrease psychological distress among Syrian refugees in Turkey: A pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC psychiatry, 22, 1-11 View

Akhtar, A., Engels, M. H., Bawaneh, A., Bird, M., Bryant, R., Cuijpers, P., Hansen, P., Al-Hayek, H., Ikkursun, Z., Kurt, G., Sijbrandij, M., Underhill, J., Acarturk, C., & STRENGTHS consortium. (2021). Cultural adaptation of a low-intensity group psychological intervention for Syrian refugees. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 19(1), 48-57. View

Fuhr, D. C., Acarturk, C., Sijbrandij, M., Brown, F. L., Jordans, M. J., Woodward, A., McGrath, M., Sondorp, E., Ventevogel, P., Ikkursun, Z., Chammay, R., Cuijpers, P., & Roberts, B. (2020). Planning the scale up of brief psychological interventions using theory of change. BMC health services research, 20, 1-9. View

Perera, C., Salamanca-Sanabria, A., Caballero-Bernal, J., Feldman, L., Hansen, M., Bird, M., Hansen, P., Dinesen, C., Wiedemann, N., & Vallières, F. (2020). No implementation without cultural adaptation: A process for culturally adapting low-intensity psychological interventions in humanitarian settings. Conflict and health, 14, 1-12. View

Bryant, R. A., Schafer, A., Dawson, K. S., Anjuri, D., Mulili, C., Ndogoni, L., Koyiet, P., Sijbrandij, M., Ulate, J., Harper Shehadeh, M., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., & van Ommeren, M. (2017). Effectiveness of a brief behavioural intervention on psychological distress among women with a history of gender based violence in urban Kenya: A randomised clinical trial. PLoS Medicine, 14(8), e1002371. View

Akhtar, A., Giardinelli, L., Bawaneh, A., Awwad, M., Al Hayek, H., Whitney, C., Jordans, M.J., Sijbrandij, M., Cuijpers, P., Dawson, K., & Bryant, R. on behalf of the STRENGTHS Consortium (2021). Feasibility trial of a scalable transdiagnostic group psychological intervention for Syrians residing in a refugee camp. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1932295. View

Sangraula, M., Greene, M. C., Castellar, D., de la Hoz, J. C. F., Diaz, J., Merino, V., ... & Brown, A. D. (2023). Protocol for a randomized hybrid type 2 trial on the implementation of group problem management plus (PM+) for venezuelan women refugees and migrants in colombia. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 21(2), 154-169. View

Coleman, S. F., Mukasakindi, H., Rose, A. L., Galea, J. T., Nyirandagijimana, B., Hakizimana, J., Bienvenue, R., Kundu, P., Uwimana, E., Uwamwezi, A., Contreras, C., Rodriguez Cuevas, F.G., Maza, J., Ruderman, T., Connolly, E., Chalamanda, M., Kayira, W., Kazoole, K... & Smith, S. L. (2021). Adapting problem management plus for implementation: Lessons learned from public sector settings across Rwanda, Peru, Mexico and Malawi. Intervention (Amstelveen, Netherlands), 19(1), 58. View

Goloktionova, A. E., & Mukerjee, M. (2021). Bringing problem management plus to Ukraine: Reflections on the past and ways forward. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 19(1), 131-135. View

Chiumento, A., Billows, L., Mackinnon, A., McCluskey, R., White, R. G., Khan, N., Rahman, A., Smith, G., & Dowrick, C. (2021). Task-sharing psychosocial support with refugees and asylum seekers: Reflections and recommendations for practice from the PROSPER study. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 19(1), 67-74. View

Nemiro, A., Van't Hof, E., & Constant, S. (2021). After the randomised controlled trial: implementing problem management plus through humanitarian agencies: Three case studies from Ethiopia, Syria and Honduras. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 19(1), 84-90. View

Van't Hof, E., Dawson, K. S., Schafer, A., Chiumento, A., Harper Shehadeh, M., Sijbrandij, M., Bryant, R. A., Anjuri, D., Koyiet, P., Ndogoni, L., Ulate, J., & van Ommeren, M. (2018). A qualitative evaluation of a brief multicomponent intervention provided by lay health workers for women affected by adversity in urban Kenya. Global mental health (Cambridge, England), 5, e6.View

Dawson, K. S., Schafer, A., Anjuri, D., Ndogoni, L., Musyoki, C., Sijbrandij, M., van Ommeren, M., & Bryant, R. A. (2016). Feasibility trial of a scalable psychological intervention for women affected by urban adversity and gender-based violence in Nairobi. BMC psychiatry, 16(1), 1-9. View

McBride, K. A., Harrison, S., Mahata, S., Pfeffer, K., Cardamone, F., Ngigi, T., Kohrt, B., Pederson, G., Greene, C., Viljoen, D., Orso, M. & Brown, A. D. (2021). Building mental health and psychosocial support capacity during a pandemic: The process of adapting problem management plus for remote training and implementation during COVID-19 in New York city, Europe and east africa. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 19(1), 37-47. View

Ali, H., & Ari, K. (2021). Addressing mental health and psychosocial needs in displacement: How a stateless person from syria became a refugee and community helper in Iraq. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 19(1), 136-140. View

Basil, M., Youssef, M., Al-Khatib, L., Shebrek, A., Akili, S., & Zakrian, M. (2021). Personal reflections on problem management plus: Written by syrian helpers at stichting nieuw thuis, rotterdam, the Netherlands. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 19(1), 118-120.

Spaaij, J., Fuhr, D. C., Akhtar, A., Casanova, L., Klein, T., Schick, M., Weilenmann, S., Roberts, B. & Morina, N. (2023). Scaling up problem management plus for refugees in Switzerland - a qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 23(1), 488. View

Brown, A. D., Ross, N., Sangraula, M., Laing, A., & Kohrt, B. A. (2023). Transforming mental healthcare in higher education through scalable mental health interventions. Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health, 10, e33. View

Fuhr, D. C., Bogdanov, S., Tol, W. A., Nadkarni, A., & Roberts, B. (2021). Problem Management Plus and Alcohol (PM+ A): A new intervention to address alcohol misuse and psychological distress among conflict-affected populations. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 19(1), 141-143. View

Knefel, M., Kantor, V., Weindl, D., Schiess-Jokanovic, J., Nicholson, A. A., Verginer, L., Schaffer, I. & Lueger-Schuster, B. (2022). Mental health professionals’ perspective on a brief transdiagnostic psychological intervention for Afghan asylum seekers and refugees. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2068913. View

Bryant, R. A., Bawaneh, A., Awwad, M., Al-Hayek, H., Giardinelli, L., Whitney, C., Jordans, M. J. D., Cuijpers, P., Sijbrandij, M., Ventevogel, P., Dawson, K., Akhtar, A., & STRENGTHS Consortium (2022). Twelve-month follow-up of a randomised clinical trial of a brief group psychological intervention for common mental disorders in Syrian refugees in Jordan. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 31, e81. View

Sangraula, M., Kohrt, B. A., Ghimire, R., Shrestha, P., Luitel, N. P., Van't Hof, E., Dawson, K., & Jordans, M. J. D. (2021). Development of the mental health cultural adaptation and contextualization for implementation (mhCACI) procedure: A systematic framework to prepare evidence-based psychological interventions for scaling. Global mental health (Cambridge, England), 8, e6. View

Pedersen, G. A., Gebrekristos, F., Eloul, L., Golden, S., Hemmo, M., Akhtar, A., & Kohrt, B. A. (2021). Development of a tool to assess competencies of problem management plus facilitators using observed standardised role plays: The EQUIP competency rating scale for problem management plus. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 19(1), 107-117. View

Hamdani, S. U., Rahman, A., Wang, D., Chen, T., van Ommeren, M., Chisholm, D., & Farooq, S. (2020). Cost-effectiveness of WHO Problem Management Plus for adults with mood and anxiety disorders in a post-conflict area of Pakistan: Randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 217(5), 623-629. View

Nyongesa, M. K., Mwangome, E., Mwangi, P., Nasambu, C., Mbuthia, J. W., Koot, H. M., Cuijpers, P., Newton, C.R., & Abubakar, A. (2022). Adaptation, acceptability and feasibility of Problem Management Plus (PM+) intervention to promote the mental health of young people living with HIV in kenya: Formative mixed-methods research. BJPsych Open, 8(5), e161. View

Fuhr, D. C., Acarturk, C., Uygun, E., McGrath, M., Ilkkursun, Z., Kaykha, S., Sondorp, E., Sijibrandij, M., Ventevogel, P., Cuijpers, P., & Roberts, B. on behalf of the STRENGTHS consortium. (2020). Pathways towards scaling up problem management plus in Turkey: A theory of change workshop. Conflict and Health, 14, 1-9. View

Pedersen, G. A., Gautam, N. C., Pudasaini, K., Luitel, N. P., Long, M. W., Schafer, A., & Kohrt, B. A. (2023). Incremental cost analysis of training of trainers and helpers in Problem Management Plus (PM+) using an Ensuring Quality in Psychological Support (EQUIP) Competency-based approach in Nepal. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 21(2), 116-126 View

Williams, N., & Kirkbride, J. B. (2024). Community-based interventions on the social determinants of mental health in the UK: An umbrella review. Journal of Public Mental Health. View