Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour Volume 7 (2025), Article ID: JMHSB-199

https://doi.org/10.33790/jmhsb1100199Review Article

Retirement Research: A Narrative Review

Tiffany Field, PhD

Touch Research Institute, University of Miami/Miller School of Medicine, Fielding Graduate University, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Tiffany Field, PhD, Touch Research Institute, University of Miami/Miller School of Medicine, Fielding Graduate University, United States.

Received date: 03rd February, 2025

Accepted date: 31st March, 2025

Published date: 02nd April, 2025

Citation: Field, T., (2025). Retirement Research: A Narrative Review. J Ment Health Soc Behav 7(1):199.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

This narrative review summarizes research on retirement published in 2024. Most of the studies are focused on late in life, voluntary retirements. In a few comparisons late life, voluntary retirements have had more positive effects than early, involuntary retirements. Studies on the effects of retirement include behavioral, emotional, cognitive and physical effects. Research is also reviewed on predictors /risk factors for retirement and buffers/protective factors for negative effects of retirement. The research on behavior changes following retirement includes a reduction in the use of medications and an increase in volunteering. The studies on emotional effects include an increase in quality of life and happiness and a decrease in loneliness and neuroticism but also an increase in depression. Research on cognitive effects includes executive function problems and greater risk for dementia. The physical effects research includes a decrease in sleep problems but an increase in biological age, frailty and a greater risk for mortality. The predictors/risk factors for retirement include female gender, less education and social support, and physical problems including poor health, disability and pain. The buffers/protective factors include education, health and mindfulness of the individual, and having a partner and available green space. Surprisingly, only one intervention study appeared in this literature which involved social support groups. Methodological limitations of this literature include the reliance on survey data and the confounding of retirement age and voluntary/involuntary retirement.

Introduction

This narrative review summarizes research on retirement published in 2024. Most of the studies are focused on late in life, voluntary retirements. In a few comparisons those types of retirements have had more positive effects than early, involuntary retirements. For example, in the Health and Retirement Study that included samples of adults greater than 50-years-old from Australia, China and the U.S., the older voluntary retirees had the lowest prevalence of loneliness versus the younger involuntary retirees who had the greatest prevalence of loneliness [1]. Surprisingly, social engagement did not modify the association between retirement and loneliness.

This review includes 40 studies on the effects of retirement including behavioral, emotional, cognitive and physical effects, as well as predictors /risk factors for retirement, and buffers/protective factors and interventions for negative effects of retirement. The empirical studies and review papers summarized here were derived from a search on PubMed and PsycINFO entering the terms retirement and the year 2024. Exclusion criteria for this review included proposed protocols, case studies and non-English language papers. The publications can be categorized as effects of retirement, predictors/ risk factors, and buffers/interventions. Accordingly, this review is divided into sections that correspond to those categories. Although some papers can be grouped in more than one category, 18 papers are focused on the effects of retirement, 13 papers on predictors/ risk factors for retirement, and 9 papers on buffers/interventions. A discussion on methodological limitations of this literature follows those sections.

Effects of Retirement

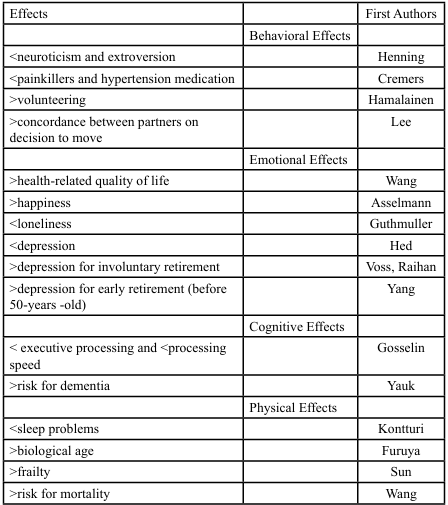

Many positive as well as negative effects of retirement have been noted in research published in 2024. These include behavioral, emotional, cognitive, and physical effects.

Behavioral Effects

Positive behavior effects of retirement appeared in this current literature. They included a reduction in neuroticism and extroversion, a reduction in the use of medications, an increase in volunteering and concordance between spouses on moving their residence.

In a study from Norway that explored the effects of retirement on personality traits, the Big Five Personality Traits Inventory was used including neuroticism, extroversion, intellect, conscientiousness, and agreeableness (N=1263) [2]. Following retirement, decreases were reported for neuroticism and extroversion. In potentially less interaction with people following retirement, the participants may have felt they had fewer opportunities to be extroverted.

In a paper entitled “The causal effect of early retirement on medication use”, a sample from Denmark reported less use of painkillers and hypertension medication and increased use of mental health medications [3]. The males in this sample reported a decrease in the use of all medications. The males may have experienced greater stress relief following retirement, for example, due to more stressful employment and/or voluntary retirement resulting in less need for medications.

In a study entitled “Is transition to retirement associated with volunteering?”, the answer is yes [4]. In this sample (N = 6200 adults greater than 50-years-old), volunteering occurred more often in individuals with greater health, education, financial situation and residence in countries with a greater gross domestic product per capita. Volunteering may have also occurred more often in the younger retirees in this relatively young sample.

In a paper entitled “Concordance in spouses’ intention to move after retirement”, 83% of middle-aged spouses (N = 1285 adults 49 to 64-years-old) from Korea were concordant on the decision to move their residence [5]. This included 29% agreeing to move and 54% agreeing to stay in their current residence. It is not clear what variables contributed to this concordance or what contributed to significantly more couples agreeing to stay versus move.

Emotional Effects

Several positive and negative emotional effects have been reported for retirement in this current literature. The positive effects include improved health-related quality of life, increased happiness, decreased loneliness, and decreased depression, although depression increased for those experiencing involuntary early retirement.

In a study from China (N= 1043 retirees), work after retirement was said to increase health-related quality of life, especially in older age retirees (> 65 years-old) [6]. In a paper entitled “Paradox of life after work”, a systematic review of 19 studies was presented [7]. Across these studies, a positive relationship between retirement and health- related quality of life was noted for 32%, a negative relationship between retirement and quality of life for 47% and no correlation was reported in 21% of the studies. It is not clear why retirement led to a negative health-related quality of life more often unless there was also a negative relationship at baseline. Alternatively, these data could mean that the absence of retirement contributed to a better health-related quality of life. The direction of this relationship may be impossible to determine in these cross-sectional studies. The authors also suggested that there are potential biases in these data due to methodological diversity, scarcity of longitudinal studies, and recent societal shifts.

Having a better health-related quality of life may have contributed to the increased happiness that has also been reported following retirement. In a study entitled “Working life as a double-edged sword”, career starters in Germany (N= 2720) were compared with retirees (N= 2007) [8]. During the five years before retirement, older adults were less satisfied, less happy, sadder and more anxious. However, in and after the first year of retirement, they were more satisfied, happier, less anxious, and less angry. The authors suggested that these data supported the role strain perspective. Although role strain has been defined as the tension experienced when a scarcity of resources such as skills impedes an individual’s ability to meet role expectations, the negative emotions during the five years prior to retirement may have also related to job burnout.

Decreased loneliness may have also contributed to the greater happiness reported for retirement. In an analysis of data from the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), decreased loneliness was reported in the long run following retirement [9]. The participants were less socially isolated by increasing their activity levels and becoming more involved. However, greater loneliness was reported by women in the short run which was likely related to their spouses not having yet retired.

The decreased loneliness may have resulted in decreased depression symptoms. For example, in a study on the Health, Aging and Retirement Transitions in Sweden (HEARTS), depression reportedly decreased in the early years of retirement (N= 527) [10]. This was noted across the retirement transition in both men and women.

Increased depression, however, has been reported by individuals who experienced Involuntary or forced retirement. In an analysis of data from the Health and Retirement Study, high scores on the Lost – Work Opportunities Scale were related to increased depression and decreased self-reported health (N=2576) [11]. Scores on that scale predicted 46% of an increased odds of negative health changes. Decreased self-reported health may have also led to involuntary retirement. As in most of these cross-sectional studies, the direction of effects is impossible to determine.

Another analysis of the Health and Retirement Study data was reported in a paper entitled “Involuntary delayed retirement” [12]. In this sample of adults greater than 65-years-old, those who desired to retire but were unable to retire due to financial constraints had greater depression, anxiety, and anger.

Retirement age has also been related to depression symptoms in a study from Korea [13]. Retirement before the age of 50 led to greater depression . In contrast, retirement at greater than 70-years- old led to less depression. In this sample, depression was also greater in females, heads of households and involuntary retirees. Age of retirement (early versus late) and involuntary/voluntary retirement are confounding variables in several of these studies and none of the studies have assessed all combinations of these two variables.

Cognitive Functions

Retirement has also negatively affected cognitive functions. In a study from Canada on executive functions and processing speed, 45 to 85-year-old adults were noted to have limited performance on the Stroop and the Mental Alteration tasks (N= 1442), suggesting executive function and processing speed problems[14]. Even more seriously is the negative effect of retirement on dementia. In a review of 10 studies, five of them suggested that later retirement was associated with a high risk for dementia [15]. Early signs of dementia might also be associated with a high risk for retirement.

Physical Effects

Retirement has had both positive and negative physical effects including decreased sleep problems, and increased biological age, frailty, and greater risk for mortality. In a study from Finland on sleep problems, the sleep problems decreased at retirement [16]. The authors suggested that the problems either decreased or the participants found it easier to live with their sleep problems.

In the study on biological age entitled “Retirement makes you old?”, a causal effect of retirement on biological age was noted in the database of the UK Bio Bank [17]. An increase in biological age was particularly noted for those required to retire by state pension eligibility requirements.

The increase in biological age may have led to the increase that has been noted in frailty following retirement. The frailty following retirement is implied by the association between continuing work after retirement and the lesser incidence of frailty [18]. In this Health and Retirement Study data analysis, workers (N= 3170) were compared to non-workers (N=2790). The protective effect of working was noted for those who were more than 65-years-old, for males, and for those with limited social activities.

Greater risk for mortality has been associated with early retirement in Taiwan [19]. In this very large sample (N= 1,762,621 adults 45 to 64-years-old), greater mortality risk was noted for the younger adults, for males, for those in the farming or fishing industry and for those with poor health conditions. It is not clear from this paper whether a regression analysis or structural equation modeling were conducted to determine the relative significance of these risk factors for mortality.

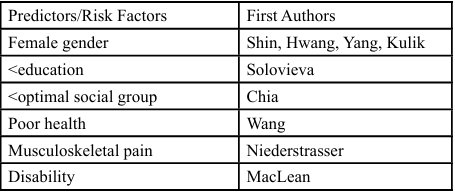

Predictors/Risk Factors for Retirement

Several predictors/risk factors for retirement have been the focus of studies in this current literature. They include female gender, education, social support, poor health, disability and pain.

Female gender has been a predictor/risk factor for retirement in four studies in this current literature. Gender differences have been noted for the transition sequences and well-being following retirement in the Health and Retirement Study [20]. In this sample (N= 633 older workers), the men transitioned from full to part-time voluntary retirement while the women moved gradually through an involuntary retirement. The disparity between males voluntarily retiring and females experiencing involuntary retirement suggests ongoing discrimination against women in the workplace.

The less well-being of the females following their involuntary retirement may have contributed to the gender disparity that was noted regarding the impact of retirement on marital satisfaction in Korea (N= 5,867) [21]. The male retirees were more satisfied with their marriages after retirement and the females were less satisfied.

The less well-being of the women and the less satisfaction with their marriages following retirement may have contributed to their experiencing greater depression than the men. In a study on the association between retirement age and the incidence of depression disorders in Taiwan (N = 84,224), depression peaked at the time of retirement [13]. Greater depression was noted in females and in the 65 to 69-year-old versus 60 to 64-year-old adults. These findings are inconsistent with those from Korea that suggested less depression in the older group [13]. These mixed findings suggest cross-cultural differences even across Asian countries.

The less well-being and the greater depression of the females post retirement may have related to their greater mental health problems and lower work satisfaction prior to their retirement. In a sample from Israel, for example (N = 78 females and 82 males), the retired females had more mental problems and less work satisfaction prior to retirement [22]. Interestingly, the men reported that they considered their wives their confidants and they reported more household labor and decision-making than the women reported.

Less education has contributed to shorter working life expectancy based on a review of 21 studies [23]. In this review, the less educated men had a 30% shorter working life expectancy and the less educated women had a 27% shorter working life expectancy.

Less social group membership has related to less retirement adjustment in 37 percent of a sample from Australia [24]. Similarly, less social support has been related to less satisfaction following retirement among middle-aged and older adults in the Singapore Life Panel (N=532) [25]. Social activities and social support have been buffers for retirement stress [26]. Workplace groups provide social interaction opportunities that would be missing without post retirement activities.

Poor health has been associated with early retirement and mortality risk in a database entitled Taiwan's National Health Insurance Research Database (N = 1,762,621 early retirees age 45 to 64) [19]. The early retirees had a greater mortality risk. Other risk factors were being a male and farming or fishing. The causes of death were gastrointestinal disorders, suicide and neurological disorders.

Musculoskeletal pain has also contributed to early retirement. In a sample from England (N=1156 retirees greater than 50 years old), frequent musculoskeletal pain led to retirement [27]. Other risk factors for early retirement in this sample were work dissatisfaction, greater social status, being a female and not receiving recognition that was expected. These are consistent with risk factors noted by other researchers. The greater social status may have facilitated the retirement.

Disability was a significant predictor/risk factor of involuntary retirement in 28% of older workers in a sample from the Longitudinal Study on Aging in Canada (N=2080) [28]. Other predictors of retirement were organization restructuring, health or stress factors, financial possibility for retirement and wanting to stop working.

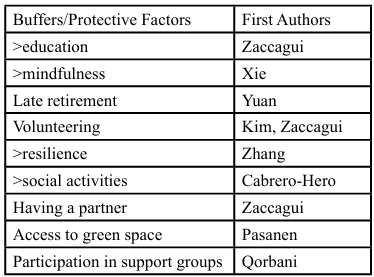

Buffers/Protective Factors for Retirement Effects

Several buffers/protective factors for retirement effects have been the focus of research in this current literature. They include education, health, mindfulness, late retirement, volunteering, social activities, having a partner and having access to green space.

In the Health and Retirement Study (N=6803), greater education led to later retirement [29]. In the Copenhagen Aging and Midlife Biobank Survey (N= 5,474), approximately 20% of the sample worked beyond retirement age [30]. Those who worked beyond retirement age were wealthier, healthier males who had a partner.

Mindfulness has also been noted as a protective factor for retirement in older adults. In a study from China (N= 748 retirees older than 60), mindfulness reduced negative affect and loneliness [31].

In the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), late retirement was considered the primary protective factor [32]. Additional buffers were health care quality and electronic social contact. These factors were negatively associated with mental health problems following retirement.

In a paper entitled “Does volunteering reduce epigenetic age acceleration among retired and working older adults?”, data from the Health and Retirement Study were analyzed suggesting that volunteering for 200 plus hours per year was a buffer for older adults (N=2605) [33]. In those who volunteered, there was less epigenetic age acceleration with a significant reduction in DNA methylation measures. Greater benefits of volunteering were noted for the retired versus the working adults. Data from another analysis of this database suggested that greater resilience resulted in slower DNA methylation and biological aging [34].

Social activities have also been effective buffers for negative effects of retirement. In the Health and Retirement Study conducted over 30 years, social activities during retirement led to greater cognitive function [26].

Having a partner was a significant buffer for negative effects of retirement in the Copenhagen Aging and Midlife Biobank Survey [30]. This buffer was not surprising, but this buffer was confounded by other buffers including being wealthier and healthier.

Having access to green space was a buffer in the Finnish Retirement and Aging Study (N= 102) [35]. In this study, having access to green space was associated with more activity during active travel on days off and retirement days. Having access to green space has been therapeutic for adults both pre and post-retirement.

The only intervention study that appeared in this literature involved participation in support groups [36]. In this study on retired older adults from Iran (N= 80), 4 support group sessions 60 to 90 minutes long were held two times per week. The participants were said to have the retirement syndrome which involved feelings of emptiness, loneliness, uselessness, lack of clear understanding of future conditions and dissatisfaction with one's performance. The support group sessions led to reduced feelings of being older and of idleness, confusion and conflict. In addition, the participants reported an increase in “trying a new direction”.

Methodological Limitations of this Literature

Several limitations can be noted for this current literature on retirement in adults. These include the reliance on self-report survey data and archival data, the lack of cross-cultural comparisons, the focus on a single variable, and the difficulty determining causality given that the studies were more frequently cross-sectional than longitudinal.

Although researchers from several Asian countries contributed to this literature, many other parts of the world were not represented. Twenty per cent of the studies were based on data from the Health and Retirement Study. This would be considered acceptable given that the sample was collected over a 30-year period, was very large (>20,000 adults over 50-years-old) and represented three countries (Australia, China and the U.S.). Several studies were conducted in different countries, but only a few studies included samples from a few countries for cross-cultural comparisons. Future studies could readily make cross-cultural comparisons via the online surveys typically used.

Most of the samples were old or older adults, which is not surprising given that retirement doesn’t typically happen in younger adults. Comparisons were rarely made across the younger 50-64-year-old versus the 65 and older groups but when they were compared, the older groups typically had more positive experiences following retirement. The age comparisons were typically confounded by the voluntary versus involuntary retirement variable. Many samples were either early, involuntary retirement or late, voluntary retirement.

Some samples were exclusively involuntarily retired adults who invariably experienced negative effects. The few comparisons on voluntary versus involuntary retirement suggested that involuntary retirement had more negative effects especially for women. In addition, the reasons for involuntary retirement were highly variable, ranging from what might be considered more acceptable involuntary retirement such as organizational restructuring to less comfortable involuntary retirement related to health issues. The severity of negative effects was rarely measured, for example, the severity of increased biological aging, frailty and the risk for dementia and mortality.

A wide variety of variables were assessed as effects of retirement (14 different variables), predictors/risk factors for retirement (9 different variables) and buffers/protective factors against negative effects of retirement (9 variables). But typically, each of the studies focused on a single variable as opposed to being a multivariate study that could determine the relative significance of the multiple variables.

At least two variables were considered both risk factors and buffers, including low education and social support as risk factors and high education and social support as buffers. In contrast, although depression was a negative effect, it was surprising that it didn't appear as a risk factor for retirement. The focus on effects and predictors would depend on the orientation of the research group and the time of the data collection. If the data were collected immediately following retirement, for example, the effects and predictors may be more reliably reported by the participants.

Despite these methodological limitations, this current literature on retirement has been informative about its effects, predictors/risk factors and buffers/protective factors. The severe negative effects of retirement on biological aging, frailty and the risks of dementia and mortality highlight the need for further research on the effects and risk factors for loneliness as well as effective buffers and therapy protocols.

Competing Interests:

The authors whose names are listed immediately below certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Funding:

The authors whose names are listed immediately below report the following details of affiliation or involvement in an organization or entity with a financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. Please specify the nature of the conflict on a separate sheet of paper if the space below is inadequate.

References

Hagani, N., Clare, P. J., Luo, M., Merom, D., Smith, B. J., Ding, D. (2024). Effect of retirement on loneliness: a longitudinal comparative analysis across Australia, China and the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health. Aug 25;78(10):602-608. View

Henning, G., Løset, G. K., Huxhold, O. (2024). Personality and 10-year personality development among Norwegians in midlife-Do retirement and job type play a role? Psychol Aging. Sep;39(6):658-671. View

Cremers, J., Nielsen, T. H., Ekstrøm, C. T. (2024). The causal effect of early retirement on medication use across sex and occupation: evidence from Danish administrative data. Eur J Health Econ. Dec; 25(9):1517-1527. View

Hämäläinen, H., Tanskanen, A. O., Arpino, B., Solé-Auró, A., Danielsbacka, M. (2024). Is Transition to Retirement Associated With Volunteering? Longitudinal Evidence from Europe. Res Aging. Oct-Dec;46(9-10):509-520. View

Lee, E., Kim, K. (2024). Concordance in Spouses' Intention to Move After Retirement Among Korean Middle-Aged Couples. J Appl Gerontol. Oct;43(10):1570-1579. View

Wang, Y., Tian, Y., Du, W., Fan, L. (2024). Does work after retirement affect health-related quality of life: Evidence from a propensity score matching study in China. Geriatr Gerontol Int. Jul; 24(7):722-729. View

Ugwu, L. E., Ajele, W. K., Idemudia, E. S. (2024). Paradox of life after work: A systematic review and meta-analysis on retirement anxiety and life satisfaction. PLOS Glob Public Health. Apr 4;4(4):e0003074. View

Asselmann, E., Specht, J. (2024). Working life as a double edged sword: Opposing changes in subjective well-being surrounding the transition to work and retirement. Emotion. Apr; 24(3):551-561. View

Guthmuller, S., Heger, D., Hollenbach, J., Werbeck, A. (2024). The impact of retirement on loneliness in Europe. Sci Rep. Nov 14;14(1):26971. View

Hed, S., Berg, A. I., Hansson, I., Kivi, M., Waern, M. (2024). Depressive symptoms across the retirement transition in men and women: associations with emotion regulation, adjustment difficulties and work centrality. BMC Geriatr. Jul 31;24(1):643. doi: 10.1186/s12877-024-05228-2. Erratum in: BMC Geriatr. 2024 Sep 25;24(1):784. View

Voss, M. W., Hung, M., Li, W., Richards, L. G., Price, P., Terrill, A., Barrett, T. (2024). Costs of Forced Retirement: Measuring the Effect of Lost Work Opportunity on Health. J Occup Environ Med. Aug 1;66(8):e343-e348. View

Raihan, M. M. H., Chowdhury, N., Chowdhury, M. Z. I., Turin, T. C. (2024). Involuntary delayed retirement and mental health of older adults. Aging Ment Health. Jan-Feb;28(1):169-177. View

Yang, H. J., Cheng, Y., Yu, T. S., Cheng, W. J. (2024). Association Between Retirement Age and Incidence of Depressive Disorders: A 19-Year Population-Based Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. Feb; 32(2):166-177.

Gosselin, C., Boller, B. (2024). The impact of retirement on executive functions and processing speed: findings from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. Jan-Mar;31(1):1-15. View

Yauk, J., Veal, B., Dobbs, D. (2024). Understanding the Link Between Retirement Timing and Cognition: A Scoping Review. J Appl Gerontol. May;43(5):588-600. View

Kontturi, M., Virtanen, M., Myllyntausta, S., Prakash, K. C., Pentti, J., Vahtera, J., Stenholm, S. (2024). Are changes in sleep problems associated with changes in life satisfaction during the retirement transition? Eur J Ageing. Mar 12;21(1):7. View

Furuya, S., Fletcher, J. M. (2024). Retirement Makes You Old? Causal Effect of Retirement on-Biological Age. Demography. Jun 1;61(3):901-931. View

Sun, L., Deng, G., Lu, X., Xie, X., Kang, L., Sun, T., Dai, X. (2024). The association between continuing work after retirement and the incidence of frailty: evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. J Nutr Health Aging. Dec; 28(12):100398. View

Wang, T. H., Chien, S. Y., Cheng, W. J., Huang, Y. W., Wang, S. H., Huang, W. L., Tzeng, Y. L., Hsu, C. C., Wu, C. S. (2024). Associations of early retirement and mortality risk: a population-based study in Taiwan. J Epidemiol Community Health. Jul 10;78(8):522-528. View

Shin, O., Park, S., Kim, B., Wu, C. F. (2024). Retirement Transition Sequences and Well-Being Among Older Workers Focusing on Gender Differences. J Gerontol Soc Work. Oct 21:1-31. View

Hwang, I. C., Ahn, H. Y., Park, Y. (2025). Gender disparity regarding the impact of retirement on marital satisfaction: Evidence from a longitudinal study of older Korean adults. Australas J Ageing. Mar; 44(1):e13373. View

Kulik, L. (2024). Sources of empowerment and mental health among retired men and women: An ecological perspective. J Women Aging. Jan-Feb;36(1):14-32. View

Solovieva, S., de Wind, A., Undem, K., Dudel, C., Mehlum, I. S., van den Heuvel, S. G., Robroek, S. J. W., Leinonen, T. (2024). Socioeconomic differences in working life expectancy: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. Mar 7;24(1):735. View

LaRue M et al. (2024). Advances in remote sensing of emperor penguins: first multi-year time series documenting trends in the global population. Proc. R. Soc. B 291: 20232067. View

Chia, J. L., Hartanto, A., Tov, W. (2024). Retirement and life satisfaction among middle-aged and older adults: A piecewise growth mixture analysis. Psychol Aging. Dec; 39(8):915-932. View

Cabrera-Haro, L., Mendes de Leon, C. F. (2024). Retirement, Social Engagement, and Post-Retirement Changes in Cognitive Function. J Aging Health. Dec 19:8982643241308311. View

Niederstrasser, N. G., Wainwright, E., Stevens, M. J. (2024). Musculoskeletal pain affects the age of retirement and the risk of work cessation among older people. PLoS One. Mar 20;19(3):e0297155. View

MacLean, M. B., Wolfson, C., Hewko, S., Tompa, E., Sweet, J., Pedlar, D. (2025). Predictors of Retirement Voluntariness Using Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging Data. J Aging Health. Jan; 37(1-2):75-95. View

Assari, S., Sonnega, A., Zare, H. (2024). Race, College Graduation, and Time of Retirement in the United States: A Thirty-Year Longitudinal Cohort of Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Open J Educ Res. Sep 5;4(5):228-242. View

Zaccagni, S., Sigsgaard, A. M., Vrangbaek, K., Noermark, L. P. (2024). Who continues to work after retirement age? BMC Public Health. Mar 4;24(1):692. View

Xie, X., Qiao, X., Huang, C. C., Cheung, S. P. (2024). Mindfulness and loneliness in retired older adults in China: mediation effects of positive and negative affect. Aging Ment Health. Jan Feb;28(1):188-195. View

Yuan, B. (2024). How the interplay of late retirement, health care, economic insecurity, and electronic social contact affects the mental health amongst older workers? Stress Health. Apr; 40(2):e3309. View

Kim, S., Halvorsen, C., Potter, C., Faul, J. (2025). Does volunteering reduce epigenetic age acceleration among retired and working older adults? Results from the Health and Retirement Study. Soc Sci Med. Jan;364:117501. View

Zhang, A., Zhang, Y., Meng, Y., Ji, Q., Ye, M., Zhou, L., Liu, M., Yi, C., Karlsson, I. K., Fang, F., Hägg, S., Zhan, Y. (2024). Associations between psychological resilience and epigenetic clocks in the health and retirement study. Geroscience. Feb; 46(1):961-968. View

Pasanen, S., Halonen, J. I., Suorsa, K., Leskinen, T., Gonzales Inca, C., Kestens, Y., Thierry, B., Pentti, J., Vahtera, J., Stenholm, S. (2024). Exposure to useable green space and physical activity during active travel: A longitudinal GPS and accelerometer study before and after retirement. Health Place. Nov; 90:103366. View

Qorbani, S., Majdabadi, Z. A., Nikpeyma, N., Haghani, S., Shahrestanaki, S. K., Poortaghi, S. (2024). The effect of participation in support groups on retirement syndrome in older adults. BMC Geriatr. Apr 12; 24(1):333. View