Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour Volume 7 (2025), Article ID: JMHSB-200

https://doi.org/10.33790/jmhsb1100200Research Article

Adult Projective Drawings in Pandemic Times: Draw-a-Person and Kinetic Family-Drawings with Associations

Alisha Jiwani1*, Sherry L. Hatcher2, Kelly J. Walk2, Collin A. Weekes2, Mona Chung2, and Chanelle Salonia2

1School of Psychology, Fielding Graduate University, 2020 De La Vina St. Santa Barbara, CA, 93105, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Alisha Jiwani, Ph.D., School of Psychology, Fielding Graduate University, 2020 De La Vina St. Santa Barbara, CA, 93105, United States.

Received date: 19th February, 2025

Accepted date: 20th May, 2025

Published date: 22nd May, 2025

Citation: Jiwani, A., Hatcher, S. L., Walk, K. J., Weekes, C. A., Chung, M., & Salonia, C., (2025). Adult Projective Drawings in Pandemic Times: Draw-a-Person and Kinetic-Family-Drawings with Associations. J Ment Health Soc Behav 7(1):200.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

This projective assessment for studying perceptions of self and family during COVID-19 was part of a project examining the adult decision-making process during the pandemic. For this research project, 110 adults aged 18-82 from the United States and Canada completed a background questionnaire and 30 pandemic-related questionnaire items. In addition, 84 participants (76%) each uploaded four projective drawings, with their accompanying written associations, of self and family as envisioned both prior to and during the pandemic, for a total of 336 drawings collected. These drawings represented Self Pre-Pandemic (SP); Self During Pandemic (SD); Family Pre-pandemic (FP) and Family During Pandemic (FD). Two coders rated each drawing with the accompanying associations for a) type of drawing: (stick figures; full figures; abstract/object-only/ non-peopled; faces only) b) figures depicted with masks c) drawings expressing affect d) activities possible before or during the pandemic e) relationship experiences and f) body image representations. Coder reliabilities were over 90% agreement. Happy faces and positive associations were dramatically more frequent for drawings and associations before versus during the pandemic, whereas ubiquitous expressions of isolation and negative affect were associated with SD and FD drawings. Examples of representative drawings with concomitant associations, for each of the four conditions (SP; FP; SD; FD) are presented, illustrated and discussed. Overall, we found that detailed, evocative expressions of affect were most prevalent in response to the projective drawings in contrast with questionnaire items, suggesting their utility for exploring experiences for persons affected by the pandemic and similar events.

Keywords: Projective Drawings, COVID-19 Pandemic, Self and Family Depictions, Canadian Participants

Introduction

Since the development of the Draw a Person (DAP) assessment, that was first conceived as a measure of cognitive ability in children, projective drawings have served as a valuable way to understand individuals’ attitudes, experiences and emotions, including for adults [10]. As Machover wrote in her classic text about the Draw-a-Person measure, “Projective methods of exploring motivations have repeatedly uncovered deep and perhaps unconscious determinants of self-expression which could not be manifest in direct communication...” [18] (p.4).

Gaining verbal and/or written associations to a person’s projective drawings can further serve as a method of indirect interview, especially as narrative associations are typically requested along with requested drawings of human figures. Participants asked to draw human figures of self and others, not infrequently include additional abstract designs and pictured objects, along with their self or family drawings. These kinds of spontaneous associative responses help inform our understanding of the meaning, experiences, and emotions for arists of any age.

An Illustration of Associations to Projective Drawings

As one example, among many compelling illustrations offered in response to a request for drawings of self and family, a sixteen-year-old girl first drew a witch’s hat on top of a rat, that she associated to her sister who “rats on her” and “acts like a witch” [13]. She further produced a picture of fire with a halo on top, associating that to her “grandmother because she acts so sweet but at home she is a demon.” For a self-drawing, she depicted a volcano on top of a mountain with a written association that stated, “People think I’m a rock…but I have a dormant volcano and will erupt” [13] (pp. 226/227).

As the literature on projective drawings with children was originally intended to serve as a measure of cognitive ability, there have been questions about the validity of projective drawings for that particular purpose [17]. Some prior studies have also utilized projective drawings to assess cognition in adults [16]. Whether or not cognitive ability can be reliably and validly assessed in this way for pariticipants of any age, there is abundant evidence suggesting that emotions are readily expressed through drawings, often more so than tend to result from interview questions alone [11,19]. The affective disinhibition that typically results with children when asked to draw pictures is likely also true also for adults. In general, projective measures can serve to stimulate expressiveness and provide information not otherwise consciously available by means of direct inquiry.

The DAP: SPED

Probably the best-known Draw a Person scoring system for assessing emotional issues in children and adolescents is the Draw a Person: Screening Procedure for Emotional Disturbance or DAP: SPED, [22]. The DAP: SPED system includes 55 criteria that can be applied to a drawing, in which each element is scored as one or zero. Scores are additive, such that lower scores are thought to represent less problematic emotional functioning than higher scores. In this evaluative system, points are added for omission of a range of features, such as hair, eyes, and fingers. There are also points scored for shading, erasures, and for an overall lack of integration in the drawing. Normed for ages 6-17, higher scores have shown a relationship to emotional problems. While analogous scoring methods are not available for adults, other than with the Formal Elements Art Therapy Scale or FEATS [7] that measures artistic development, frequencies can be used to count specific elements of adult drawings, together with qualitative thematic coding for analyzing participants’ accompanying associations to each of their drawings.

Related to the DAP for use with individuals, the Kinetic Family Drawing (K-F-D) assessment has been useful for assessing family dynamics [3]. The DAP and K-F-D coding systems have both shown strong rater reliability (84%-95%), [14,28], demonstrating that reliable coding of drawings is possible.

In clinical practice, drawings have been employed with people of all ages, including in art therapy, in order to assess emotional expressiveness, conflict, possible abuse, cognition and more [6,8].

A Previous Study During a Public Health Crisis with Drawings Data

The present study is part of a larger project on adult decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic, in which adults from around the United States and Canada were asked for background information and responses to questionnaire items. They were further requested to produce and upload four drawings, along with providing written associations for each drawing.

The demographic and narrative questions included in the present study were based on a study conducted during another public health crisis in the 1970s, when there was a packaging mix-up at a chemical factory that produced both cattle feed and the fire retardant PBB, spreading this carcinogen throughout the food chain in the state of Michigan [15]. PBB was found at various levels in the bodies of all state residents and was typically excreted at the rate of only 1% per year. However, as a lipophilic substance, PBB was uniquely and alarmingly excreted in much larger amounts via breast milk, posing a profound psychological dilemma for nursing mothers whose milk was contaminated.

Two public health experts helped construct a questionnaire for these mothers [15], and several projective measures were part of the study, including a written story-telling exercise in response to illustrations of nursing mothers. This exercise elicited expressions of strong feelings, including defensive denial that were significantly related to laboratory-reported actual levels of PBB in the mothers’ breast milk.

In the present study, participants were asked to create their own original drawings depicting Self and Family, as envisioned both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. They were also asked to provide written associations for each of the drawings they produced [15]. The drawings with accompanying associations evoked a range of affects as well as reported behaviors and losses. Given this rich data, we decided to focus on the projective drawing findings, with some of the related questionnaire data, in order to describe and illustrate important features of participants’ psychological experience during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The few studies featuring projective drawings during the COVID-19 pandemic, primarily focused on children’s drawings, [1,12]. None but a single-case geriatric study of projective drawings [26] was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic with an adult participant. This overall general dearth of adult studies that utilize projective drawings, likely reflects a tradition of using this projective method primarily with children, including as a form of play therapy and for purposes of encouraging expressiveness.

For adults as well as for children, projective drawings can serve as a form of displacement, yielding relatively uncensored content, along with increased expressions of affect. Particularly during stressful times, such as in context of a public health crisis, when people may need to marshal psychological defenses in order to deal with poorly understood health risks and decision-making quandaries, a projective measure can be facilitative of expressiveness that is less accessible by objective assessment methods alone.

Materials and Methods

Timing of the Present Study

Data for this study were collected during the Winter of 2021 when the COVID-19 pandemic was greatly affecting peoples’ lives, including in the United States and Canada. Many individuals were working entirely or partly from home, some had lost their jobs and most schools were offering at least some virtual instruction. Mask-wearing was commonly required indoors, at transportation hubs and in medical centers. In general, transitions to telehealth and telepsychology services were in demand and burgeoning [25].

Conflicting advice was rampant, including from government officials and public health experts. At that point in time, the pandemic had been in people’s awareness for about a year and was continuing to affect their lives in multiple ways: psychologically, relationally, in the workforce and more [20]. Risks of COVID-19 persist to the present day.

Participants

Following on IRB approval, eight researchers from across the United States and Canada, employed snowball sampling methods [5,21] to gain a final sample of 110 participants. Recruitment fliers described the nature of the research to potential participants who needed to meet inclusion criteria as English-speaking adults, over 18 years-old and who affirmed they were able to respond to a multi-part, online questionnaire, requiring approximately 60-90 minutes of their time.

Procedure

Participants meeting the above criteria who were interested in participating in the study were sent the link to a Qualtrics survey. Upon agreeing to the IRB-approved informed consent and then completing the study, participants were offered a $20 Amazon e-gift card and the option to receive feedback on group findings. Those who completed a majority of the requested tasks were included in the study, whether or not they uploaded the requested drawings.

Measures

After agreeing to the informed consent that was presented on the first Qualtrics screen, participants were asked to answer a multi-part questionnaire, with 14 background questions (Appendix C), including about their age, gender, ethnicity, education and religion, followed by a series of 30 questionnaire items (Appendix B), regarding their pandemic-related knowledge, experiences, opinions, feelings and decision-making. Lastly, participants were tasked with creating and uploading four separate drawings. It should be noted that the informed consent gave permission for their deidentified drawings to be reproduced in presentations and publications. Participants’ names were not connected with their questionnaire responses or with the drawings they produced.

Instructions for creating the drawings were to: 1) “Draw a picture as you envisioned yourself pre-Covid-19 pandemic” 2) “Draw a picture as you envision yourself during the Covid-19 pandemic” 3) Draw a picture of your family as you envisioned them pre-Covid-19 pandemic and 4) “Draw a picture of your family as you envision them during the Covid-19 pandemic.”

Participants were also requested to “write below each drawing what you notice in terms of feelings or anything else about your drawings.” Instructions further assured that artistic ability was not important and participants were provided with the means for uploading their drawings via Qualtrics.

Data Analysis

The drawings were each rated by pairs of psychology doctoral students and faculty coders for a) type of drawing: stick figures; full figures; abstract/object-only/non-peopled; or faces only b) figures depicted with facial masks c) drawings that expressed emotions or affect (e.g. “how depressing it is to lose freedoms and how to spend your time”) d) activities identified as possible only before and/or during the pandemic e) relationship effects of the pandemic (e.g. “unable to see grandkids…sad) and f) body image representations.

Coders attended training sessions with a senior faculty to learn procedures for interpretation of projective drawings [13] and for analyzing associations to the drawings using thematic content analysis [2].

Frequencies for the types of drawings (full figure; stick figure; abstract/objects only figures; faces only) were calculated for each of the four requested drawings (Self-Pre-pandemic, Self During Pandemic; Family Pre-Pandemic and Family During Pandemic). Numbers of masks depicted were also reported across the four conditions as were numbers of happy versus sad faces. Spontaneous depictions of such items that participants included such as drawings of televisions and computer screens (e.g. “tendencies to rely on screens to communicate/get entertainment”) as well as other objects were noted. Frequencies of figures and objects drawn were calculated by rater pairs with 100% reliability.

Written associations to each of the drawings were thematically analyzed by rater pairs for activities that were drawn representing before and during the pandemic, about self and family relationships before and during the pandemic and about food buying habits and body image (e.g. “fat and broken”). For the written associations accompanying each drawing, code books were developed summarizing the thematic analysis for each set of associations, with verbatim examples [3]. The inter-rater reliability for thematic analysis of the written associations accompanying each of the drawings was over 90%. Rater disagreements were resolved by consensus.

The findings from the projective drawings data are presented here, including illustrative, pictorial examples and associated text (Appendix A).

This study was not preregistered. The informed consent allows only the research team and IRB to access the full dataset. The study analysis code is not available. Data is securely retained by researchers. IRB Approval (No.21-1103, Fielding Graduate University).

Reflexivity Statement

The researchers and participants who are from Canada and the United States faced similar challenges during the COVID pandemic. Our research team observed strong feelings engendered by the pandemic, both in themselves and from research participants; Researchers also reported feelings about the pandemic for which there were not consistent outlets for expression. We processed some of our own experiences to ensure that coding of data was not personally affected by our own experiences. Altogether, the use of projective drawings with participants offered unique ways for them to share their affective experiences, including with their written associations to each drawing they produced. Many who participated in our study spontaneously expressed appreciation for the opportunity for artistic self-expression and reflection. Similarly, we as researchers experienced the resulting data as rich, evocative and meaningful, leading to self-reflection and reflections as a research group.

Results

The sample consisted of 110 participants from the United States and Canada. Twenty-six participants who completed the questionnaire items chose not to post drawings. Eighty-four participants completed each of the four requested drawings, for a total of 336 drawings produced, each including the participant’s written associations.

The sample was comprised of 69.7% females, 28.4% males, 0.9% unidentified ‘other’, and 0.9% unidentified. For the participants, 45% were between the ages of 36 and 64 years; 33% were between 18-35 years of age and 22% were over 65 years of age. Regarding race, 78% of the participant sample self-identified as Caucasian or White; 6.4% were Asian or Pacific Islander; 6.4% self-identified as multi-race; 5.5% identified as Latino/a/Hispanic and 3.7% identified as Black/African American or African/Canadian. About one third of the sample were participants from Canada and the rest were from the United States.

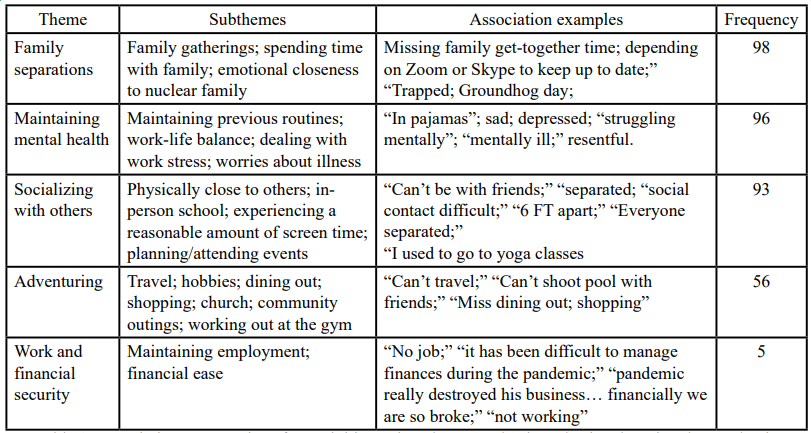

Table 1: Associations to Drawings for Activities Enjoyed Pre-Pandemic and Missed During the Pandemic

Types of Drawings

Four types of drawings were produced across the sample: full figure drawings (N=30); stick figure drawings (N=226); abstract/non peopled (or objects only) drawings (N=26) and face-only drawings (N=54), (See Appendix A).

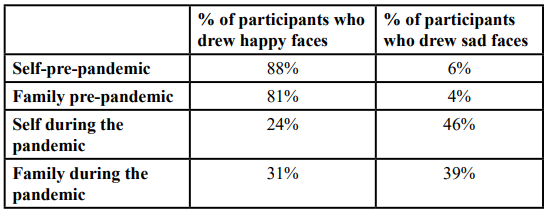

For the Self Pre-pandemic drawings, (SP), 74 out of 84 or 88% of the participants drew happy faces, and only 5 out of 84 or 6% depicted sad faces, χ2(1, 84) = 60.3, p = <0.001. For Family Pre pandemic drawings (FP), 68 out of 84 or 81% drew happy faces and only 3 out of 84 or 4% depicted sad faces, χ2 (1, 84) = 59.5, p = <0.001. For Self During Pandemic drawings, (SD), 20 out of 84 or 24% faces were depicted as happy and 39 out of 84 or 46% were sad faces, χ2 (1, 84) = 6.1, p = 0.013. For Family During pandemic drawings (FD), 36 out of 84 or 31% of the faces were drawn as happy and 33 out of 84 or 39% were depicted as sad, χ2 (1, 84) = 0.13, p = 0.718 (See Figures 17, 18, 24, and 25).

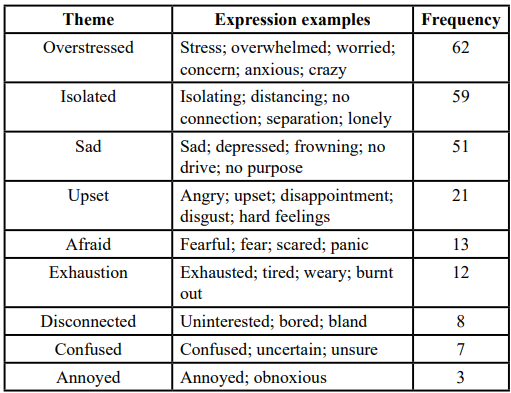

Each of these depictions was consistent with participants’ written associations. SD and FD associations most often referenced feelings of isolation, deprivation, lack of control, mask-wearing mandates, activity and interpersonal restrictions, television and computer screen overload and troubled emotions (See Figures 26, 27, and 28). Some of the pictures across age groups illustrated body image changes and food related concerns such as weight gain during the pandemic (See Figures 19 and 20).

Older Adults’ Concerns

Associations to their drawings provided by older adult participants evidenced their greater caution and concern regarding pandemic-related risk, as illustrated by one senior participant’s associations to a drawing of their family during the pandemic:

My parents didn’t leave the house much as my mom is highly immuno-compromised. My dad had to be very pragmatic about how to take care of their needs while also keeping himself and my mom safe…My mother was often worried and fearful about catching the virus. My brother and his family were stuck together for a considerable amount of time in their house together as my brother tried to work from home...The adults were overwhelmed, exhausted, and stressed. (Figures 21, 22, and 23).

Questionnaire data supported associations to the drawings. As related specifically to food-related concerns, participants were asked to “Please identify any of the following decisions you made as a result of COVID-19” as it pertained to “change in food buying habits” and “change in stores or suppliers of your food.” Responses to these items indicated that food buying behaviors were significantly changed for older adults, χ2(2, 110) = 6.05, p = 0.049 with more seniors ordering food deliveries and engaging less in-person grocery shopping, as compared with the two younger participant age groups.

More generally, older participants tended to endorse more a conservative approach to their lifestyles during the pandemic in response to the following questionnaire item: “Would you say you have been a) very conservative b) medium conservative or c) relatively uninhibited in going about your usual lifestyle during the pandemic?” An ordinal logistic regression indicated that older participants’ during-pandemic narrative responses showed significantly less inclination to take risks than those younger, χ2 (50,110) = 80.81, p=.004.

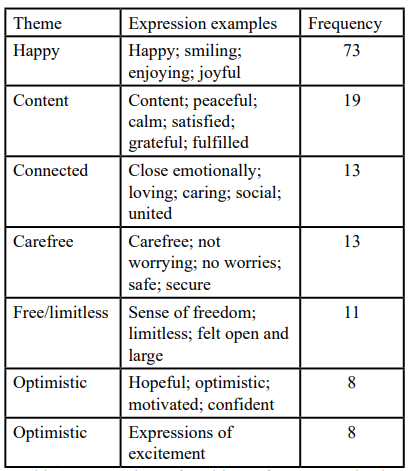

Activities Enjoyed Pre-Pandemic and Missed During Pandemic

Across age groups, other drawings depicted and described participants’ experiences of missing the kinds and variety of active participation they were accustomed to engaging in pre-pandemic (See Figures 8, 9, 10, and 11). Participants consistently drew pictures with associated text, illustrating family and friend relationships and activities that they had been able to enjoy pre-COVID-19, but were missing during the pandemic. There were multiple pictures with accompanying text describing loss of travel, shopping, interrupted school, remote work, lapsed daycare arrangements, inaccessible dining out, missed exercise classes, a lack of sports participation and more (See Table 1).

Mask-wearing

Thirty-five out of 84 or 42% of participants drew at least one figure with a protective mask and many of the drawings showed multiple figures with masked faces. The number of masks depicted was approximately equal for Self During Pandemic and Family During Pandemic (See Figures 12, 13, and 14).

Expressions of Affect

A wide range of affect was depicted throughout the drawings and accompanying associations, more so than in response to the questionnaire items regarding experiences and feelings during the pandemic. There were numerous examples of vivid affect expressed in the drawings and related associations, totaling N=744 affect words in the written associations to drawings, with an average count of affect words of nine, per each participant.

As an overall assessment of contentment or lack thereof expressed in associations to their drawings, 70% of the participants described themselves as less happy during the pandemic than prior and 63% depicted and reported that their families were less happy during the pandemic. Pre-pandemic associations to self and family drawings included expressions using the terms joy, gratitude, calm, satisfied, peaceful, excited, united, free, limitless, optimistic, motivated, confident, and adventurous (See Figures 17, 18, 24, and 25). During pandemic drawings, associations most commonly depicted and expressed affects in terms such as: lonely, broken, sad, stressed, stoic, exhausted, skeptical, nostalgic, disappointed, and worrying (See Table 3). There were also a number of abstractly configured drawings that depicted a sense of turmoil and confusion (See Figures 15 and 16).

Despite a preponderance of expressions indicating negative affect in the pandemic drawings, there were also some associations that referenced expressions of resiliency and optimism during the pandemic (See Figures 30 and 31). One example was posted by a participant who wrote next to their drawing, “During the pandemic I was exhausted, getting worn out from all the operational and policy changes, but was still trying to make the best out of the circumstance and maintain a peaceful disposition”.

There were only a handful of drawings in which pre-COVID-19 self and family drawings were depicted in a more positive and optimistic light than self and family as envisioned during the pandemic, (See Figures 30 and 31). Most sequences across the four drawings showed more happiness and a greater sense of freedom, prior to the pandemic than during (N=51). One example of a typical sequence across the four drawings (SP, FP, SD and FD) is illustrated by one participant (See Figures 32, 33, 34, and 35).

Discussion

In order to assess experiences, decision-making, relationships, and emotional reactions during the COVID-19 pandemic, 110 participants completed an informed consent document, a background questionnaire, 30 interview questions and lastly, were requested to upload four drawings, with their associations to the drawings they produced: for Self-pre-pandemic (SP); Self during pandemic (SD); Family pre-pandemic (FP) & Family during (FD) pandemic.

Eighty-four respondents posted four drawings each that were then coded and analyzed, including for their accompanying written associations to each drawing produced. Two coders rated each drawing with accompanying associations for: a) type of drawing: stick figures; full figures; abstract/object-only/non-peopled; or faces only b) drawings depicted with masks on people c) drawings expressing a range of affects d) activities depicted as possible only before or during the pandemic e) relationship effects of the pandemic; f) body image depictions - and more.

Drawings of happy faces produced for Self and Family before and during COVID-19 were dramatically different, with happy faces drawn primarily for pre-pandemic depictions and sad faces drawn more for during the pandemic representations. Ubiquitous expressions of isolation and negative affect (See Table 4) were associated with SD and FD. However, a couple of outlier responses referenced greater happiness during the pandemic. Some reasons for that alluded to by participants included their having increased time with family, an ability to work from home and/or their tendency toward social anxiety. Several participants also noted attitudes of resiliency and optimism in their strategies for coping with the COVID-19 pandemic.

In summary, few previous studies have detailed and depicted the emotional responses of adults across age groups who were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic [4,9]. Throughout our analysis of projective drawings and associated text, we found prevalence of strongly expressed affects and conflict, along with decision-making quandaries during the COVID-19 pandemic experience. It is clear from these findings how extraordinarily difficult the ongoing pandemic has been for adults and how extensively and ubiquitously it affected their family, social relationships, travel, work, leisure activities, food habits, self-care practices, mental/physical health, and overall quality of life [29,30]. Participants’ projective drawings and their associations to the pictures produced make abundantly clear that the COVID-19 pandemic was traumatic in many ways. That projective drawings provide a space for uninhibited expression of feelings, not similarly accrued from questionnaire items or other objective assessments, constitutes an argument for making greater use of this form of projective assessment, particularly in situations involving trauma and uncertainty.

The use of snowball sampling in the present study, although resulting in a widely distributed sample geographically, nonetheless constituted a non-random sample. Although the researchers, located across the United States and Canada were encouraged to seek a diverse sample of participants, even greater racial and ethnic diversity would have been preferable, though diversity across gender and age was achieved. While 84 participants completed the requested questionnaire items and drawings, 26 participants chose to complete the questionnaire items only. It would have been helpful to have learned why they made that choice.

The use of projective drawings can arguably be recommended for research studies on a range of topics, particularly for studying challenging and traumatic situations, such as those that occur during public health crises. Projective drawings, with concomitant associations, can serve to elicit and identify people’s feelings and experiences that apply well cross culturally [27], since the use of projective drawings for assessment has long been viewed cross-culturally applicable. As emphasized, in the early literature on this subject, “Graphic communications occur regardless of age, skill or culture” and that, “expressions of anger, love, joy and strength are common social images across cultures” [18] (p. 7).

Whereas Draw-a Person measures were historically a standard component of full-battery psychological assessments, this type of assessment measure has largely disappeared in regular use by psychologists, especially with the advent of managed care. Coding this kind of data requires special training and can be time-consuming.

However, as is apparent from our findings, it is not only for children that projective drawings can serve to facilitate expressiveness that may otherwise be less accessible. Adults, as well, appear to freely share affect and psychologically motivated concerns through the medium of their artwork and related associations [23]. Extensive research on the value of expressiveness has demonstrated positive psychological, and even improved physiological effects, when people have outlets for emotional expressiveness [24]. As such, we might argue for renewed interest in the use of projective drawings by psychologists as part of an assessment protocol and in research studies.

Competing Interests:

The authors of this study declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Appreciation to Dr. Katherine McGraw for administering the Faculty Research Grant to Dr. Hatcher that funded participant gift cards and Qualtrics functionality for uploading drawings. Special appreciation to the participants for their generous contributions of time and for their evocative narratives and artwork. Thanks also to Michelle Forgione and Leticia Berg for assisting with data collection.

References

Alabdulkarim, S. O., Khomais, S., Hussain, I. Y. & Gahwaji, N. (2022) Preschool Children’s Drawings: A Reflection on Children’s Needs within the Learning Environment Post COVID-19 Pandemic School Closure, Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 36:2, 203-218. View

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. View

Burns, R. (1982). Self-growth in families: Kinetic Family Drawings (K-F-D); research and application. New York: Brunner/Mazel View

Calma-Birling, D., & Zelazo, P. D. (2022). A network analysis of high school and college students’ COVID-19-related concerns, self-regulatory skills, and affect. American Psychologist, 77(6), 727–742. View

Chaim, N. (2008). Sampling Knowledge: The Hermeneutics of Snowball Sampling in Qualitative Research, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11:4, 327-344. View

Finn, S. & Tonsager, M. (1997). Information-gathering and therapeutic models of assessment: Complementary paradigms. Psychological Assessment, 9(4), 374-385. View

Gantt, L. (2016). The Formal Elements Art Therapy Scale (FEATS). In D. E. Gussak & M. L. Rosal (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of art therapy, 569–578. Wiley Blackwell. View

Garritt, I. (2004). The case for formal art therapy assessments. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 21(1), 18-29. View

Gonçalves, A. R., Barcelos, J. L. M., Duarte, A. P., Lucchetti, G., Gonçalves, D. R., Silva e Dutra, F. C. M., & Gonçalves, J. R. L. (2022). Perceptions, feelings, and the routine of older adults during the isolation period caused by the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study in four countries. Aging & Mental Health, 26(5), 911-918. View

Goodenough, F. L. (1928). Studies in the psychology of children’s drawings. Psychological Bulletin, 25, 504-512. View

Gross, J., & Hayne, H. (1998). Drawing facilitates children's verbal reports of emotionally laden events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 4(2), 163–179. View

Haghanikar, T. M., & Leigh, S. R. (2022). Assessing children’s drawings in response to COVID-19. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 36(4), 697-714. View

Handler, L. & Thomas, A.D. (2014). Drawings in Assessment and Psychotherapy: Research and Application. New York: Routledge. View

Handler. L. & Habenicht, D. (1994). The Kinetic Family Drawing technique: A review of the literature. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63, 440-464. View

Hatcher, S. L. (1982). The Psychological Experience of Nursing Mothers upon Learning of a Toxic Substance in their Breast Milk. Psychiatry, 45, 172 - 183. View

Imuta, K., Scarf, D., Pharo, H., & Hayne, H. (2013). Drawing a close to the use of human figure drawings as a projective measure of intelligence. PloS one, 8(3), e58991. View

Lehman, E. B., & Levy, B. I. (1971). Discrepancies in estimates of children's intelligence: WISC and human figure drawings. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 27(1), 74–76. View

Machover, K. (1949). Personality Projection in the Drawing of the Human Figure. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas. View

Malchiodi, C. A. (2017). Art therapy approaches to facilitate verbal expression: Getting past the impasse. In C. A. Malchiodi & D. A. Crenshaw (Eds.), What to do when children clam up in psychotherapy: Interventions to facilitate communication, 197–216. Guilford Press. View

Marmarosh, C. L., Forsyth, D. R., Strauss, B. & Burlingame, G. M. (2020). The psychology of the COVID-19 pandemic: A group-level perspective. Group Dynamics: Theory Research, and Practice, 24(3), 122-138. View

Naderifar, M., Goli, H., & Ghaljaie, F. (2017). Snowball sampling: A purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides in development of medical education, 14(3). View

Naglieri, J.A. & Pfeiffer, S. I., (1992). Performance of disruptive behaviors disordered and normal samples on the Draw A Person: Screening Procedure for Emotional Disturbance. Psychological Assessment, 4, 156-159. View

Oster, G. D., & Gould, P. (1987). Using drawings in assessment and therapy: A guide for mental health professionals. Brunner/ Mazel. View

Pennebaker, J. W. (1997). Opening up: The healing power of expressing emotions, New York: Guilford Press. View

Pierce, B. S., Perrine, P. B., Tyler, C. M., McKee, G. B., & Watson, J. D. (2021). The COVID-19 telepsychology revolution: A national study of pandemic-based changes in U.S. mental health care delivery. American Psychologist, 76(1), 14- 25.View

Renzi, A., Verrusio, W., Evangelista, A., Messina, M., Gaj, F., & Cacciafesta, M. (2021). Using drawings to express and represent one's emotional experience during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A case report of a woman living in a nursing home. Psychogeriatrics, 21(1), 118–120. View

Ritzler, B. (2004). Cultural applications of the Rorschach, apperception tests, and figure drawings. In M. J. Hilsenroth & D. L. Segal (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment, Vol. 2. Personality assessment, 573–585. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. View

Williams, T. O., Jr., Fall, A.-M., Eaves, R. C., & Woods-Groves, S. (2006). The Reliability of Scores for the Draw-A-Person Intellectual Ability Test for Children, Adolescents, and Adults. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 24(2), 137–144. 29. View

Vincenzes, K. A., MacGregor, I., & Monaghan, M. (2021). A Beacon of Light: Applying Choice Theory to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour, 3(2), 151-155. View

Walk, K., Jiwani, A., & Hatcher., S.L. (2023). Stories to Tell Future Generations about the COVID-19 Pandemic: American and Canadian Adults Share their Perspectives. Manuscript under review.