Journal of Mental Health and Social Behaviour Volume 7 (2025), Article ID: JMHSB-201

https://doi.org/10.33790/jmhsb1100201Research Article

Strength Training as Recovery Capital in Substance Use Disorders

Lori Davidson1*, PhD, HS-BCP, CRS, Annabelle Nelson2, PhD

1Assistant Professor, Montgomery County Community College, 101 College Drive, Pottstown, PA 19464, United States.

2Professor, Fielding Graduate University, 2020 De La Vina Street, Santa Barbara, CA 93105,United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Lori Davidson, PhD, HS-BCP, CRS, Assistant Professor, Montgomery County Community College, 101 College Drive, Pottstown, PA 19464, United States.

Received date: 14th April, 2025

Accepted date: 24th June, 2025

Published date: 26th June, 2025

Citation: Davidson, L., & Nelson, A., (2025). Strength Training as Recovery Capital in Substance Use Disorders. J Ment Health Soc Behav 7(1):201.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

This phenomenological study examines the role of strength training, specifically weightlifting, in increasing recovery capital among individuals with substance use disorders (SUD). While various modalities address the comorbid aspects of addiction, this research provides qualitative data on the efficacy of strength training. The study explores the impact of weightlifting on recovery capital, focusing on increased physical strength, positive self-image, healthy brain chemistry, and peer support to reduce relapse. Using a phenomenological method and photo elicitation, nine participants in recovery with strength training programs participated in openended interviews and provided photos illustrating the significance of strength training in their recovery. Seven themes emerged from the data: (a) choice, (b) self-acceptance, (c) focus, (d) symbiotic paradigm, (e) power, (f) autonomy, and (g) control. These themes are integrated into a model of transformation through strength training, highlighting its impact on recovery. Participants reported positive changes in body image, increased physical and mental strength, and transformation towards a healthier life, maintaining abstinence throughout.

Keywords: Addiction, Weightlifting, Phenomenology, Relapse, Treatment, Drugs, Rehabilitation

Introduction

Substance Use Disorders (SUD) represent a significant public health crisis in the United States, often leading to severe morbidity. Medically, SUD is a term used to describe the use or misuse of illegal substances such as methamphetamines or legal substances such as alcohol [1]. National surveys from 2007 [2] indicate a rise in both fatal and nonfatal opioid overdoses, further complicated by increased methamphetamine use and the availability of high-quality heroin. Approximately 2% of U.S. adults live in households with family members who have SUDs, and 10% of these households include a member with a drug abuse disorder. In 2017, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) declared a public health emergency due to the opioid crisis [3]. Results from a national survey in 2023 reported that 28.9 million people in the U.S. had an alcohol use disorder (AUD) in the past year [4]. The National Alliance on Mental Illness [5] reported that in 2019, 9.5 million U.S. adults with a mental illness also had a substance use disorder. Despite new interventions in harm reduction, like needle exchange programs and injection sites, the societal stigma surrounding addiction hinders many harm reduction efforts [4]. This stigma perpetuates the myth that addiction is a moral failing or weakness, given the voluntary nature of initial substance use. Lemonick [6] notes that sustainable treatment methods for addiction have seen little improvement over the years.

Contemporary recovery models for substance use disorders are primarily designed to promote abstinence and support reintegration into society of productive individuals. Common interventions include behavioral therapies, counseling, medication-assisted treatment (MAT), and case management [4]. MAT is frequently employed in the treatment of opioid use disorders involving substances such as heroin, fentanyl, and oxycodone [7]. However, there are several medications available for alcohol use or misuse, such as Naltrexone and Acamprosate [8]. Another widely used approach is inpatient rehabilitation, with over 14,500 specialized facilities across the United States [4]. However, emerging research has raised concerns about the long-term efficacy of inpatient treatment in sustaining recovery outcomes [9]. Recovery metrics often emphasize short-term abstinence following treatment rather than evaluating long-term recovery and quality of life [10].

Historically, many individuals with SUDs have relied on peer-based recovery frameworks such as Narcotics Anonymous (NA), which emphasizes complete abstinence and fosters recovery capital through community support and accountability [11,12]. NA is a 12-step program model offering a spiritually oriented approach to substance use recovery centered around a sequence of guiding principles that encourage personal accountability, mutual support, and ongoing self-reflection. Originating from Alcoholics Anonymous, NA adapts the 12-step framework to address addiction more broadly rather than focusing on a specific substance. However, both models emphasize the importance of community, anonymity, and a connection to a self-defined higher power, often facilitated through group meetings, sponsorship relationships, and service to others in recovery. While widely accessible and free of charge, 12-step models may not resonate with all individuals, particularly those seeking a non-spiritual or more clinical approach. However, they remain a foundational component of the recovery landscape and are frequently used in conjunction with other treatment modalities.

Despite the availability of various treatment modalities, sustained recovery remains a significant challenge. Relapse rates among individuals in recovery are substantial, with estimates ranging from 40% to 60% [13], and some studies suggesting rates as high as 70% to 80% [14,15]. These statistics highlight the need for a more nuanced understanding of recovery trajectories and the factors that support long-term success.

Recovery Capital in Physical Exercise

An intervention that may support long-term recovery may need to have additional recovery capital. Recovery capital is "internal and external resources needed to achieve and maintain recovery or healthy life resources" [13]. Physical exercise (PE) fosters capital by creating healthy life resources and overcoming stigmas. PE also affects brain plasticity, influencing cognition and well-being [16]. This evidence includes experimental and clinical studies on neurotransmitters, including dopamine and serotonin, which show that PE generates "structural and functional" changes in the brain [17]. Regarding the neural linkage findings, there is preclinical and clinical evidence from studies showing that PE alters the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), decreasing drug abuse vulnerability [15,18]. Furthermore, exercise has many of the same positive neurological effects that mediate drug use and behavior [15].

The research literature mentions physical activity, fitness, and exercise. All of these terms fall under the categories of physical fitness activity (PFA), physical activity (PA), and physical exercise (PE). In most research studies, the PA designation typically includes team sports, cycling, swimming, walking, running, and aerobic exercise [19]. A study regarding attitudes toward physical fitness activities (PFA) reported that heroin users like to see themselves as active and enjoying physical pastimes [20]. Bardo and Compton [18] found that one-third of successful abstainers attributed exercise as a resource to maintain their recovery. Another study detailed information on clients remaining abstinent through PFA [20].

Across several articles, researchers documented that high levels of physical exercise (PE) were associated with low levels of relapse, whereas little to no PE was associated with higher levels of relapse [13,15,18,20]. PE supports and increases recovery capital by "promoting reorganization of leisure time, a way to manage anxiety or mood, cope with emotional upset or stress, build self-esteem and confidence, and spend active time with positive peer groups" [20].

PE creates peer support that appears in the form of social connection in recovery and is a vital component of recovery capital during the abstinence stage of recovery, which is a critical time to combat relapse [18]. The prolonged abstinence that recovery capital supports reduces cravings and gives someone with SUD a better chance of preventing relapses [4]. A meta-analysis [21] examined physical activity in people with opioid or amphetamine addiction, documenting that the illegal drug use habit was replaced by an exercise habit during stressful situations that might prompt a relapse. Also, the exercise intervention improved mood and sleep, while also reducing cravings.

Some psychiatrists recommend PE integration in all mental health provider settings, particularly in programs supporting those with psychiatric diagnoses. Other researchers report that PE improves self-concept, total mood disturbance, depression, fatigue, positive engagement, revitalization, tranquility, and tension [19,22-26].

In their meta-analysis on the interaction of exercise and addiction, Patterson et al. [27] found that about 75% of the studies they reviewed reported a significant improvement in addiction-related outcomes (e.g., more days abstinent, reduced cravings). Roessler's [28] research focused on the results of exercise on behavior and body image and found that participants improved self-reported quality of life and reduced drug intake. There is strong support for PE in treating SUD, but few have examined strength training as a form of PE.

One study by Nowakowski et al. [27] studied strength training in terms of outcomes for mental health. In their grounded theory research, they reported that participants who experienced PTSD, depression, and trauma found improvement in their mind-body connection, overcoming dysregulation and hyper- and hypo-vigilance. This research on strength training and previous research on the positive effects of PE for addiction offers strong support for applying strength training to the mental health dysfunction of SUD.

Strength training sometimes referred to as resistance training, which is not frequently included in the PE category, is a specific type of exercise prescription to enhance strength and power through the progression of workloads [28]. Workloads refer to weight-bearing movements; these movements may include body weight, free weights, or machine-assisted weightlifting. This type of movement is beneficial during the time-sensitive initial phase of recovery since this phase needs to promote positive peer interactions, enjoyment, self-esteem, cognitive functioning, confidence to remain abstinent, and an increase in overall physical health [26].

Strength training has the potential to produce the following recovery capital: (1) improved health and mood [19]; (2) increased positive neurotransmitter activity of dopamine and serotonin [17]; (3) a supportive peer environment [29]; and (4) enhanced body image to mitigate negative internal and external stigma. With these potential components of recovery capital, strength training may help some people with SUD maintain their recovery.

This qualitative research study involved phenomenological interviews with people with SUD who had maintained recovery and participated in strength training. A phenomenological method uncovers the essence of experience, providing insights into how strength training can prevent relapsing. The guiding research question was: What is the essence of the experience of strength training as a means of preventing relapse in addiction?

Materials and Methods

Researcher Positionality

The researcher of this study has 20 years of lived experience in recovery. This background shaped the research question and gave her the unique ability to interpret the data. As someone in long-term recovery, the researcher believes sharing successful pathways is crucial. Strength training exercises have been the key to her success, and she believes this form of movement can support others.

Participants

Participants were recruited through a snowball sampling method to meet specific inclusion criteria related to substance use recovery and strength training. Eligibility requirements included being at least 21 years of age, self-identifying as being in recovery from a substance use disorder, having maintained a minimum of six consecutive months of recovery, and engaging in a strength training routine during both the abstinence and maintenance phases. The study was inclusive of individuals with any substance use disorder, regardless of the specific substance involved.

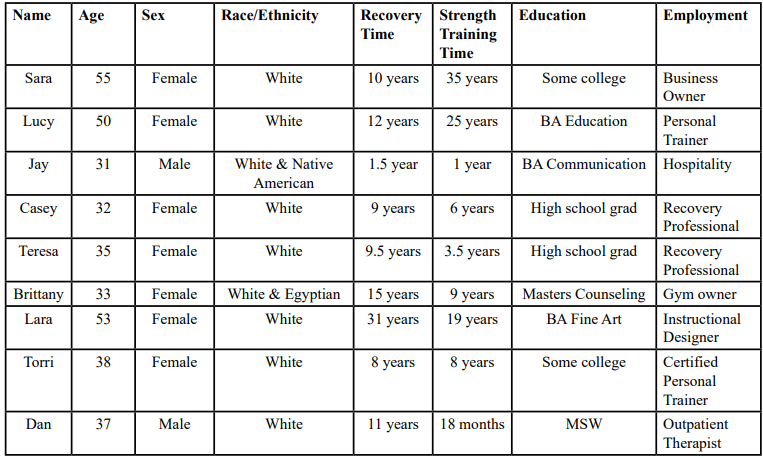

Recruitment efforts were conducted through social media platforms, fitness centers, and recovery-related networking groups. Nine participants (seven women and two men), all residents of the United States—specifically in Georgia, Louisiana, and Pennsylvania—were interviewed. Participants ranged in age from their early 30s to mid-50s. On average, they had maintained recovery for 11 years (range: 1.5 to 31 years) and had engaged in strength training for an average of 12 years (range: 1 to 25 years).

Demographic and background information, including recovery duration, strength training experience, ethnicity, education, and employment status, is presented in Table 1. All but three participants consented to use their real names in the study.

The researcher collected data through nine semi-structured interviews. In qualitative research, participants may struggle to articulate their emotional responses or the deeper meaning of lived experiences. As Polanyi noted, "we know more than we can tell" [30]. This implicit or tacit knowledge is often better conveyed through creative or symbolic forms such as art, music, film, or photography.

This study incorporated photo elicitation, a qualitative technique in which participants submit or respond to visual imagery to prompt discussion and support participants in expressing their experiences. Participants were asked to provide photographs of strength-based activities that supported their recovery. These images served as conversational anchors during the interviews, enriching the dialogue and facilitating a deeper exploration of participants' recovery journeys. As Glaw et al. [31] explain, integrating visual media in qualitative interviews is a widely accepted and effective strategy for eliciting narrative depth and participant engagement. Photographs also created a shared reference point between the researcher and the participants, enhancing relational connection and interpretive clarity [32].

Visual data supports phenomenological research as a way of accessing meaning that may be difficult to convey verbally. For instance, Shinebourne and Smith [33] used participant-generated drawings to explore the transformation from active addiction to recovery, revealing experiential dimensions that were otherwise hard to articulate.

Following the semi-structured interview protocol and using participant-provided photos as a springboard, open-ended questions were posed to explore each individual's recovery and strength training experiences. Questions focused on key moments in their recovery process, perceived impacts of strength training, and the interplay between physical activity and personal transformation. Additionally, several questions were informed by Van Manen's [30] four existential themes: lived space (spatiality), lived body (corporeality), lived time (temporality), and lived human relation (relationality/communal experience)—which served as a framework to guide participants' reflections on the embodied and contextual aspects of their lived experience.

Phenomenological Data Interpretation

The investigator of this study used a phenomenological approach to interpret the data collected from the interviews and photos. The philosophical framework of phenomenology focuses on the essence of an individual's experience, the what and how, simply to understand the experience, its underlying meanings to the individual, and its meaning for others. Therefore, using this approach, the participants guided the research, as "human experience makes sense to those who live it, prior to all interpretations and theorizing" [34]. This approach holds that only those who experience a phenomenon can truly interpret it, and phenomenological traditions ensure flexible data interpretation throughout the research process.

Data interpretation was performed in two phases. The first phase of the process was to apply phenomenological techniques to the data from the transcribed interviews, and the second phase required sorting and categorizing the participants' photos. During phase one, it was not uncommon for patterns and new elements to emerge as the interpretation was underway. In this step, called horizontalization, these new elements can change a researcher's perspective [35]. These identifiable patterns are referred to as "distinctive ways of seeing" [36] by way of the participants.

Upon completion of the interpretation, the study's co-author reviewed and consulted on the methodology. By consensus of the researchers, seven phenomenological themes of the interpreted results are presented here.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Fielding Graduate University. Before engaging in the study, all participants electronically submitted signed informed consent documents to the researcher.

Results

Seven phenomenological themes emerged from our interpretations: choice, self-acceptance, focus, symbiotic relationship, power, autonomy, and control. These themes relate to various domains of recovery capital, including psychological benefits, health, and overall well-being. Participants emphasized the importance of relationships, a key component in recovery capital literature.

Theme Quotes and Descriptions

Choice

While some participants admitted to using substances during their initial introduction to strength training, several emphasized that dedication to the training increased their ability to place value on their lifeworld of recovery. "Lifeworld" refers to the personal, subjective world of everyday experiences and perceptions that shape an individual's reality. Participants discussed how the learning curve in strength training created motivation and drive within them. The more they trained, the more they wanted to learn. Becoming strong and mastering the movements took some participants to world levels in their lifting, creating an internal resource of pride over their accomplishments. For other participants, even small accomplishments, like completing a movement or lifting a weight they could not lift the previous week, also gave them this internal resource.

I finally decided to completely clean my life up; it was like I had already kind of slowed down, cut things out, just had my like, binge weekend, binge two days, like, every month, every six weeks. And as I got more serious about training, just the fact that it was hindering my progress, like, what's the point of eating right? Training, right? And then I'm going to mess it up and basically have to recover from two days of nonsense that I had already done that enough in my life. It [using] wasn't serving me in any way. Sara

Self-Acceptance

Participants shared personal stories of family dysfunction or trauma surrounding food, exercise, and body image. After sharing their stories and reviewing the photo submissions, their overall impression of themselves and their mood improved. Several participants mentioned liking the look they achieved through strength training and the health feelings encompassing their achievements.

Because one of my goals, you know, being there is to lose weight, you know, because when you get sober, you get like a little chubby and stuff. So, like, my mindset in relation to, like, if I wasn't doing CrossFit, changed you know, and now I know like I need that energy and stuff like that. So that's how my thinking has changed a lot. Jay

Focus

Participants explained how strength training created deep inner connections for them and brought to life those connections that may have been severed due to substance use, improving their overall mental well-being and self-awareness. The experience of strength training requires a keen focus on somatic connection. Several participants in the study discussed how strength training brought them back to themselves by improving their self-awareness. They expressed feelings of disconnection during their active addiction, and in seeking recovery, some reported finding the spiritual connection that now gives them internal strength. Participants expressed visions and plans for the future.

The connection between mental and physical has become so intermeshed that [is] one of the things that really is so influential to me when I am lifting, and it was like a eureka moment…. So, after rehab, I made the mental connection, and the mental connection was, was key for my recovery. Lucy

Symbiotic Paradigm

Through addiction, the relationship to self, others, and a higher power is superseded by the substance of choice. However, with strength training, participants generalize the physical strength they gain to find balance and improve their quality of life. More than half of the participants in the study claimed that strength training had saved their lives. Addiction is isolating, a toxic relationship. Their new lifeworld will provide a way to seek forgiveness and form new relationships. Many participants discussed a spiritual struggle early in their recovery, while others reported finding a higher power through recovery. More than half of the participants discussed how movement makes them feel alive and connected to something spiritual. Some participants discussed how strength training creates the mind and body connection or awareness that influences their spiritual life or the desire for one.

…, and I just had to stay focused and not waste a single second. And it went so well. I was like, like, just driven; I was goal oriented. I didn't do any of like this self-doubting, self-defeating like, none of that shit. I just like, did exactly what I needed to do. And I exceeded my own expectations. Brittany

Power

Participants share instances of feeling strong and powerful during strength training sessions or because of a strength training achievement. Participants reported that having the physical power to complete a movement impacted their mental health, creating mental strength. Several participants also described how the aesthetic progressions or improvements in their physiques make them feel physically and mentally stronger.

Working out, it was one of the best things I think I ever did for my recovery. I started feeling good; I was looking good. Like, I felt like my skin was glowing, I was happier. I had this outlet; it helped me in so many ways. Casey

Autonomy

Because substance use disorder often leads to isolation and self-focused behavior, participants described how gaining physical strength through training fostered a shift toward greater personal development. Strength training gave them a sense of accomplishment and self-confidence, which extended beyond the activity to support their recovery journey. They shared the emotional benefits of helping others in their recovery as well as collaborating with others who may not be in recovery in their new lifeworld. This process encouraged a growing sense of autonomy—not as solitary independence, but as feeling supported and empowered to be themselves through their evolving capabilities. The discipline and structure of strength training created an environment where participants could build trust in their physical and mental resilience, reinforcing their belief in their ability to take control of their health and identity.

He said, I really want to, like, spotlight members and, like, their experiences, or like, what made them excited about coming in to, do CrossFit, or strength train or anything. And he was like, do you mind like, writing me up something that, like, shows how CrossFit has helped your recovery? It felt like really, it was powerful moment that somebody was interested in the benefits that I received from doing this. Teresa

Control

A phrase often used in the powerlifting world, "What the mind can see, the body can achieve," came to the researcher after identifying this theme during the data interpretation. Because substance use disorders have great control over our minds and bodies, those in recovery often struggle with regaining that control. Participants shared the desire to live with intention, whether to be a better person or engage in self-development. A few participants acknowledged that they were able to be kind to themselves and have found ways to control mishaps in their lives in a healthy way.

And when I started training on a regular basis, it was my one hour that was mine. I didn't have any demands as a mom on me because I had childcare for that one hour. And my ex-husband wasn't berating me or in my face about anything for that one hour. It was something I could control because I kind of in hindsight, I look back, and man, my life was out of control. I know that's why I went to do that, because I needed that haven, this one hour is all about me. Lara

Results Conclusion

A second-level analysis of the themes revealed a sequential progression of recovery facilitated through strength training. Participants initially made a deliberate choice to engage in strength training to support their recovery. This choice was followed by a shift from negative self-perceptions—particularly related to body image—toward a growing sense of self-acceptance and the belief that change was possible. Over time, participants reported improved focus and the emergence of a symbiotic relationship between their internal and external experiences. This transformation strengthened their commitment to recovery, enhanced self-perception, and empowered them to support others in similar journeys. As this growth continued, participants described developing a deeper sense of internal power and autonomy, a greater connection capacity, and a renewed sense of agency and control over their overall health.

The essential themes of the participants' experiences created a model of stages to show the elements of recovery capital in strength training, which is presented in Figure 6, as a model of stages of transformation for recovery.

Discussion

That was like, the first time I'd ever like really experienced, like, feeling cared for, you know, like, loved and like, people being patient with me and stuff like that. Once I had that I started to really, you know, see that, like, maybe I have something worth fighting for, you know. Jay

Participants reported that strength training fundamentally transformed their self-perception from being addicts to individuals with positive self-images and the physical and mental strength to manage their lives. They transitioned from being controlled by substances to controlling their choices, from isolation to helping others and accepting help. Regarding the "choice" theme, participants described their learning curve in strength training as creating an internal resource of pride. The theme of "self-acceptance" highlighted overcoming family dysfunction and past trauma, leading to positive body image and mood. The "focus" theme, associated with the attentional demands of weightlifting, helped participants reconnect with their bodies and improve self-awareness. Participants claimed that strength training saved their lives and, at the same time, made them feel alive. The "symbiotic paradigm" theme revealed that physical strength catalyzed mental strength, empowering participants to choose health. They also reported gaining "power" as they moved from being controlled by substances to exercising control over their lives.

There are numerous factors contributing to relapse among individuals with substance use disorders (SUD). Smith and Lynch [15] report a 70% likelihood of relapse within the first year of entering treatment. The findings of this study offer insight into how specific psychosocial themes—Choice (developing the ability to act from strength rather than weakness), Focus (cultivating a clear vision of the self through body, mind, and spirit), and Autonomy (experiencing empowerment both individually and in relation to others)—contribute to building the internal and external resources necessary for recovery capital. These themes expand on existing literature by emphasizing the internal relationship with the self and the external support of community, both critical components of sustained recovery.

The current findings align with and extend research on recovery capital presented in the introduction. Themes such as power and focus suggest that strength training may improve physical and mental health, potentially mitigating structural and functional damage to the brain's neurotransmitters [17]. The theme of self-acceptance reinforces previous research advocating for the reduction of both internal and external stigma associated with addiction [37].

A particularly compelling finding was the role of community and social support within strength training environments. Echoing prior research on recovery [29], 22 participants identified the gym as a critical social connection site. This mirrors peer support frameworks commonly seen in 12-step programs [12]. Several participants credited their growth and confidence to mentors, coaches, or peers who introduced them to strength training. Many referred to their workout partners as their "gym family," underscoring the trust and emotional bonds developed in shared physical practice. These relationships—marked by mutual encouragement, belief in one another, and collective effort—emerged as meaningful external resources for sustaining recovery.

The findings illustrate the multifaceted nature of recovery maintenance. Themes such as focus, control, and autonomy were consistently interwoven with participant reflections on flow, balance, and holistic integration of the self—mind, body, and spirit. These phenomenologically inspired insights invite further exploration into the emotional and existential transformations that may accompany long-term recovery.

Another significant outcome was the reported increase in participants' perceived ability to exercise choice. As they progressed in their training, participants described a growing desire to learn, improve, and push their limits. For some, this led to competitive achievement at elite levels; for others, accomplishing small personal goals—lifting a new weight or mastering a movement—fostered internal pride. In all cases, strength training emerged as a catalyst for reclaiming agency. Many participants reflected on the contrast between their ability to make empowered decisions in recovery versus their limited sense of choice during active addiction. Strength training became a tangible means of "choosing right."

The themes of focus and autonomy were also linked to an increase in self-awareness. Participants often described feeling disconnected during active substance use, while recovery—and particularly strength training—facilitated a reawakening of spiritual connection and clarity. Several participants expressed future-oriented visions, many of which centered around continued engagement with strength training. For some, this lifestyle became foundational to their identity and recovery, offering a structured path forward and reinforcing purpose and discipline.

Overall, the findings suggest that strength training can serve as a powerful modality for recovery. Over half of the participants stated that strength training "saved their lives." They described how physical practice fostered a sense of being alive and nurtured a connection to something greater than themselves. Strength training created a synergy of mind–body–spirit that supported emotional healing and spiritual growth. Within this framework, recovery capital—comprised of internal resilience and external support—can be cultivated through strength-based movement practices, offering individuals in recovery a sustainable foundation rooted in purpose, balance, and connection.

Limitations

While this study offers valuable insights into the intersection of strength training and recovery capital, several limitations must be acknowledged. As is typical of qualitative research, the findings are not intended to be generalizable to all individuals in recovery from substance use disorders. Rather, the phenomenological approach employed here seeks to provide in-depth, contextually rich descriptions that illuminate patterns of meaning and lived experience within a specific population. These insights contribute to a deeper understanding of recovery as it is experienced by individuals who integrate strength training into their healing process.

A primary limitation of the study is the lack of participant diversity, particularly with respect to socioeconomic status, gender, age, and ethnicity. Most participants identified as female and were drawn from a limited geographic and demographic range. As a result, the findings may not fully reflect the experiences of individuals from different racial or ethnic backgrounds, men, or those from varying social and economic contexts. Future research should seek to include more diverse participant groups to explore how cultural, social, and structural factors may influence the role of strength training in the development of recovery capital across broader populations.

Additionally, it is important to consider that not all individuals may have positive associations with strength training. For some, previous negative experiences—such as injury, body image concerns, or exposure to toxic gym environments—could limit their engagement or lead to different outcomes than those described in this study. These experiences may shape how participants perceive the role of strength training in their recovery, and their absence from the current sample may result in an overly positive portrayal.

Finally, several participants reported prior or current professional experience in fields such as SUD rehabilitation, personal training, or fitness instruction. These experiences may introduce a bias, as these individuals could possess a more favorable or structured understanding of strength training than the general population in recovery. Their perspectives may differ from those with no formal background in fitness, potentially skewing the findings toward more informed or idealized interpretations of its benefits.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that strength training is a scalable and effective recovery strategy for individuals with substance use disorders. Integrating certified personal strength trainers (CPST) into the treatment process could enhance the support provided by treatment centers. This study demonstrates that strength training can help individuals in recovery prevent relapses as they transition from treatment to outpatient programs. The results encourage further research and provide practitioners with tools to predict relapses based on engagement levels in strength training. Additionally, strength training could complement 12-step program models, offering a holistic approach to recovery.

Throughout the study, participants commented on the feelings evoked during training and positive changes to their appearance, which instilled a sense of pride. Strength training works from the outside in to help people discover their power in order to control their lives and maintain recovery. Increasing recovery capital in this way supported the participants in feeling physically better while working on an aesthetically pleasing look, giving them the confidence to be more emotionally vulnerable.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Johns Hopkins Medicine. (2025). Substance Use Disorder. View

Schulden, J. D., Thomas, Y. F., & Compton, W. M. (2009). Substance abuse in the United States: findings from recent epidemiologic studies. Current psychiatry reports, 11(5), 353- 359.View

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2018). What is the U.S. opioid epidemic? View

National Institute on Drug Abuse (2019). Drug topics. View

National Alliance on Mental Illness (2020). NAMI. View

Lemonick, M. (2019). The science of addiction. Time, special edition, 8-13.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Treat opioid use disorder. View

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2021, January). Effective Health Care Program. View

Dennis, C. B., Davis, T. D., Bernardo, K. R., & Kelleher, S. R. (2017). Enhancing health-conscious behaviors among clients in substance abuse treatment programs. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 17(3), 291-306. View

American Addiction Centers. (2021, February 8). Drug rehab success rates and statistics. View

Narcotics Anonymous (2018). NA. World Service Office. View

White, W., Budnick, C., & Pickard, B. (2011). Narcotics Anonymous: Its history and culture. Counselor, 12(2), 10-15. View

Simonton, A. J., Young, C. C., & Brown, R. A. (2018). Physical activity preferences and attitudes of individuals with substance use disorders: A review of the literature. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(8), 657-666. View

Bart, G. (2012). Maintenance medication for opiate addiction: the foundation of recovery. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 31(3), 207-225.View

Smith, M. A., & Lynch, W. J. (2012). Exercise as a potential treatment for drug abuse: Evidence from preclinical studies. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2(82), 1-10. View

Weinberg, R. S., and Gould, D. (2015). Foundations of sport and exercise psychology, 6th ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. View

Mandolesi, L., Polverino, A., Montuori, S., Foti, F., Ferraioli, G., Sorrentino, P., & Sorrentino, G. (2018). Effects of physical exercise on cognitive functioning and well-being: biological and psychological benefits. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9. View

Bardo, M. T., & Compton, W. M. (2015). Does physical activity protect against drug abuse vulnerability? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 153, 3-13. View

Firth, J., Solmi, M., Wootton, R. E., Vancampfort, D., Schuch, F. B., Hoare, E., Gilbody, S., Torous, J., Teasdale, S., Jackson, S., Smith, L., Eaton, M., Jacka, F., Veronese, N., Marx, W., Ashdown-Franks, G., Siskind, D., Sarris, J., Rosenbaum, S., . . . Stubbs, B. (2020). A meta-review of "lifestyle psychiatry": The role of exercise, smoking, diet and sleep in the prevention and treatment of mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 19(3), 360- 380.View

Neale, J., Nettleton, S., & Pickering, L. (2012). Heroin users' views and experiences of physical activity, sport and exercise. International Journal of Drug Policy, 23(2), 120-127. View

Zhang, Z., & Liu, X. (2022). A Systematic Review of Exercise Intervention Program for People With Substance Use Disorder. Frontiers in psychiatry, 13, 817927. View

Conner, K. O., Copeland, V. C., Grote, N. K., Koeske, G., Rosen, D., Reynolds III, C. F., & Brown, C. (2010). Mental health treatment seeking among older adults with depression: the impact of stigma and race. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(6), 531- 543. View

Kiraz, S., & Yıldırım, S. (2023). The effect of regular exercise on depression, anxiety, treatment motivation and mindfulness in addiction: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Substance Use, 28(4), 643-650. View

Mazyarkin, Z., Peleg, T., Golani, I., Sharony, L., Kremer, I., Shamir, A., (2019). Health benefits of a physical exercise program for inpatients with mental health; a pilot study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 10-16. View

Way, M.J., A.D. Del Genio, I. Aleinov, T.L. Clune, M. Kelley, and N.Y. Kiang, (2018). Climates of warm Earth-like planets I: 3-D model simulations. Astrophys. J. Supp. Ser., 239, no. 2, 24, View

Westcott, W. L. (2012). Resistance Training Is Medicine: Effects of Strength Training on Health. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 11, 209-216. View

Nowakowski-Sims, E., Rooney, M., Vigue, D., & Woods, S. (2023). A grounded theory of weight lifting as a healing strategy for trauma. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 25, 100521. View

American College of Sports Medicine. (2007). ACSM's resources for the personal trainer. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. View

Laudet, A. B., Savage, R., & Mahmood, D. (2002). Pathways to long-term recovery: a preliminary investigation. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 34(3), 305-311. View

Van Manen, M. (1997). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Routledge. View

Glaw, X., Inder, K., Kable, A., & Hazelton, M. (2017). Visual methodologies in qualitative research: autophotography and photo elicitation applied to mental health research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1609406917748215. View

Wilhoit, E. D. (2017). Photo and video methods in organizational and managerial communication research. Management Communication Quarterly, 31(3), 447–466. View

Shinebourne, P., & Smith, J. A. (2011). Images of addiction and recovery: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the experience of addiction and recovery as expressed in visual images. Drugs: education, prevention and policy, 18(5), 313- 322. View

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Sage. View

Rehorick, D. A., & Bentz, V. M. (Eds.). (2008). Transformative phenomenology: Changing ourselves, lifeworlds, and professional practice. Lexington Books. View

Jorgenson, J., & Sullivan, T. (2010). Accessing children's perspectives through participatory photo interviews. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(1). View

Stoltman, J. J., Marra, A., Uppercue, K., & Terplan, F. M. (2022). Reporting on addiction: an innovative, collaborative approach to reduce stigma by improving media coverage and public messaging about addiction treatment and recovery. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 241. View