Journal of Political Science and Public Opinion Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JPSPO-122

https://doi.org/10.33790/jpspo1100122Research Article

Considering The Costs of Circuit Conflict

Adamu K Shauku

Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Buffalo State University, 1300 Elmwood Avenue, Buffalo, NY 14222, Office: Cassety Hall 221, United States.

Corresponding Author: Adamu K Shauku, Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Buffalo State University, 1300 Elmwood Avenue, Buffalo, NY 14222, Office: Cassety Hall 221, United States.

Received date: 26th March, 2025

Accepted date: 31st May, 2025

Published date: 03rd June, 2025

Citation: Shauku, A. K., (2025). Considering The Costs of Circuit Conflict. J Poli Sci Publi Opin, 3(1): 122.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

The organ of national government charged with authoritatively resolving disputes over the meaning and application of national law frequently produces non-uniform interpretations of national law through the issuance of conflicting holdings by the circuit courts of appeals, the intermediate tier of its three-tiered hierarchy. High caseloads, limited Supreme Court review, and the absence of a formal consensus mechanism across regional appellate jurisdictions make occasional disagreement inevitable and long-enduring. While regional variation has potential benefits, there are also potential costs which some court watchers regard as intolerable. These costs include the propensity to cause unfairness to litigants, nonacquiescence among federal agencies to conflicting authority, economic harms to multicircuit actors, and repetitive litigation from litigants seeking to initiate or exploit circuit conflict. This paper makes two contributions. First, it conceptualizes concerns raised about regional variation in ways that render them susceptible of empirical assessment. Second, it exploits a novel data set of 151 circuit conflicts across four legal subject areas in an initial effort to empirically evaluate the merits of those concerns. Overall, I find that a non-trivial number of legally significant conflicts persist indefinitely, validating the concerns of critics. More study is needed to determine the net impact of this phenomenon on the fairness and efficiency of the judicial system.

Keywords: Law and Courts; Federal Judiciary; Percolation; Regional Variation

Introduction

"While we note that the law in the Seventh Circuit differs from the law in this circuit, that issue does not concern us here…” U.S. v. Salgado, 6th Cir. 2001 An irony lay at the heart of the U.S. federal judiciary. The organ of national government charged with authoritatively resolving disputes over the meaning and application of national law frequently produces what many of its creators hoped a national court system would forestall: “contradictory decisions [from] a number of independent judicatories” (Federalist 22). Through the issuance of conflicting holdings by the U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals—the intermediate tier of the system’s three-tiered hierarchy—the same provision of constitutional, statutory, or administrative law can take a different meaning and application in each of the twelve regions over which these circuit courts preside. Instituted in the 1890’s to relieve the Supreme Court of its appellate caseload, the courts of appeals were created as subject-matter generalists with regional jurisdiction modelled on the same circuits used to facilitate the earlier travels of Supreme Court justices [1]. Due to the regional independence of these ‘sister circuits,’ the recent proliferation of federal law, and the limited supervisory capacity of the U.S. Supreme Court, a substantial proportion of intercircuit conflicts appear to linger indefinitely. This phenomenon makes possible the cultivation of distinct bodies of law in the twelve regions over which these appellate courts preside, a fact that has become so commonplace as to be readily passed over in the Salgado opinion quoted above.

Regarding this regional variation, jurists and court scholars fit roughly into three camps. Precisionists “place a higher value on stability, uniformity, and predictability” in national legal development and regard regional variation of federal law as a flaw [2,3]. Percolationists “emphasize the value of flexibility, experimentation, and adaptation” and regard regional variation as a feature [2,4]. Between these two poles are those whom we might call trivialists, who assume circuit conflicts are so few in number, brief in duration, and/or small in legal significance as to be a “tolerable” quirk in the system [5,6]. Yet these intuitions have been subject to only limited empirical investigation.

This study makes two primary contributions. First, it catalogs existing concerns over regional variation and frames those concerns in a manner susceptible of empirical investigation. Second, it exploits a novel data set with significant advantages over data relied upon in prior studies in order to evaluate whether and to what extent those concerns are warranted.

This study is organized as follows. Section 1 reviews existing literature on circuit conflict—highlighting the concerns raised by scholars, jurists, and government commissions and study groups. Section 2 details the disadvantages of prior methods of identifying circuit conflicts and introduces a novel method relied upon here. Section 3 introduces the data this process yields and analyzes that data for evidence of the concerns raised regarding circuit conflict and regional variation. Section 4 discusses the implications and limitations of these findings. Section 5 concludes with a look ahead to future study.

Existing Literature on Circuit Conflict

While it has been supposed that the regional structure of the federal judiciary "assures that the uniformity principle will be frequently violated” [7], structure alone does not determine whether judicial outputs will be harmonious. “Harmony among coordinate units of an organization, like compliance by lower units to higher, flows from the ways in which the individuals operating within each organizational division understand their collective work” [8]. Decisional independence among the regional appellate courts can be traced to a deliberate—albeit not inevitable—choice by the U.S. Supreme Court. Less than a decade after the establishment of the intermediate courts of appeals, the Supreme Court rejected a petitioner’s argument that the Seventh Circuit should be bound by a rule announced previously by the Eighth Circuit. The Court grounded its reasoning in the co equality of courts of appeals as “coordinate tribunals”, the obligation of each Article III judge “to dispose of cases according to the law and the facts [and] decide them right”, the possibility of error via “the indiscreet action of one [circuit] court”, the utility of limiting the scope of any one circuit’s error so that “the whole country [is not] tied down to an unsound principle”, and an expectation of eventual Supreme Court review and resolution (Mast, Foos & Co. v. Stover Manufacturing Co., 177 U.S. 485, 488-489 (1900)). Thus, “uniformity of decision” within the system’s middle tier was deliberately sacrificed in pursuit of error-spotting, a minor sacrifice to be endured “until a higher court has settled the law” (Mast, Foos & Co. v. Stover Manufacturing Co., 177 U.S. 485, 488-489 (1900)).

Since the time of the Mast opinion, however, there have been several consequential changes in the institutional environment which undermine the Court’s reasoning. The increasing federalization of American law has led to dramatic increases in lower court caseload [9] even as the Supreme Court has reduced its own caseload [10]. Algero [11] describes the development as follows:

From 1891 until at least the early 1950s, the Supreme Court settled almost all conflicts that arose between the federal appellate courts regarding federal law. Today, the Supreme Court does not grant certiorari as of course when a writ application is based on a conflict between federal courts of appeals. Such a practice is no longer feasible given the Court's docket limitations and the large number of cases for which review has been sought alleging intercircuit conflicts. The reality is that in most cases litigated in the federal system, the federal appellate court is the court of last resort (613).

Despite its potential for error-spotting [12,13]—the utility of which many scholars have questioned [3,14-17]—the expectation that all or even most conflicts would be resolved has been defeated by a federal caseload crisis.

Most significantly for present purposes, however, is the fact that the majority of conflicts apparently persist indefinitely [11,18,19]. As Beim and Rader observed “many conflicts are created each year—far more than are resolved each year” [20]. Given limitations in both its role orientation and capacity, the Supreme Court appears most likely to review and resolve politically salient conflicts which provide it with the opportunity to announce broad policy [21,22]. Whether lingering conflicts should give rise to concern is an open question. Answering it requires greater precision in defining the concerns themselves followed by close empirical examination of circuit conflicts.

The most systematic prior attempt to empirically assess the tolerability of circuit conflict is Hellman’s authoritative study in the 1990’s, and that is where I begin in developing a framework for considering conflict costs. Hellman looked to the text of the congressional statute commissioning his study for relevant factors. I likewise begin with the text of the statute. The Judicial Improvements Act of 1990 directed the Federal Judicial Center to focus its attention on conflicts unresolved by the Supreme Court and to consider whether each conflict:

(1) imposes economic costs or other harm on persons engaging in interstate commerce;

(2) encourages forum shopping among circuits;

(3) creates unfairness to litigants in different circuits; or

(4) encourages nonacquiescence by Federal agencies in the holdings of the courts of appeals for different circuits that are unlikely to be resolved by the Supreme Court (JIA 1990, Sec. 302).

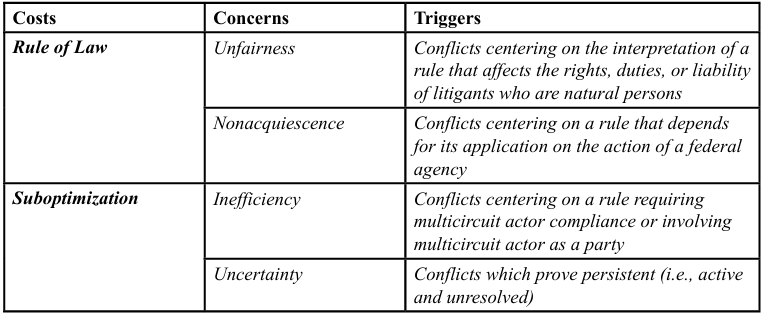

From these factors, we can identify four concerns which collapse into two cost categories.

Factors 3 and 4 in the statutory list are essentially normative concerns. The nature of the unfairness concern was best articulated in the earlier Hruska Report:

Where differences in legal rules applied by the circuits result in unequal treatment of citizens with respect to their obligations to pay federal taxes, their duty to bargain collectively or their liability to criminal sanctions, solely because of differences in geography, the circumstance is admittedly an unhappy one.

The nonacquiescence concern is similar but focused on uniform administration. Federal agencies, which are charged with the nationwide administration of federal law, confront multiple co equal juridical authorities in different regions. Consequently, they sometimes must “choose to apply the Ninth Circuit rule over the Eleventh Circuit rule, or vice versa, or…acquiesce nationwide to one circuit's view, essentially ignoring any contrary interpretations” [23]. As Daniel Meador observes:

One of the most basic features of law is that it embodies a set of rules and principles applicable to everyone in like manner throughout the jurisdiction it purports to govern… [L]egal doctrine differing because of the happenstance of the place of litigation and of the particular judges sitting on the case is hostile to the reign of law [24].

Many scholars and jurists regard the propensity for unfairness and nonacquiescence as a fundamental threat to the “integrity of courts” [25] and as deviations from the “rule of law” [26]. They can be lumped together as rule of law costs.

Despite their conceptual overlap, each of the rule of law costs are triggered under different circumstances. Unfairness is triggered in any conflict centering on the interpretation of a rule that affects the rights, duties, or liability of litigants who are natural persons. The normative import here rests on the prospect that actual people are treated differently under the same law based upon the arbitrary placement of a juridical boundary. Nonacquiescence is triggered in any conflict centering on a rule that depends for its application on the action of a federal agency. The normative import here rests on the expectation of the uniform administration of a single body of law by a single sovereign.

Factors 1 and 2 of the Judicial Improvements Act present distinct difficulties. As the report of the Federal Courts Study Committee indicates, the first of these concerns regards “economic costs or other harm to multicircuit actors, such as firms engaged in maritime and interstate commerce [19]”. Though national firms already face compliance costs associated with operating in different states, the addition of several more jurisdictions with different requirements further add to these burdens. Moreover, while states are distinct political authorities, “[c]ircuits lack… attributes of sovereignty that make jurisdictional boundaries meaningful” [25], and “for law that we think of as federal—that is, nationally uniform—[such variation] is at least unusual” [10]. This concern is one of national economic inefficiency associated with multifarious compliance.

Factor 2 of the statutory list is forum shopping. Forum shopping refers to any instance in which a litigant confronting a choice of venue in more than one circuit makes the choice strategically based upon the prospect of a more favorable result in Circuit A rather than in Circuit B. As Hellman put it, “whenever forum shopping is a possibility, it would tempt anyone who, in the ordinary course, would be subject to an unfavorable rule” [5]. But, the real concern stems not from forum shopping per se but from variation in federal law— both actual and potential—inherent in a national judicial system managed largely from its middle tier by twelve centers of co-equal authority [27]. The mere possibility that the Sixth Circuit might hold differently than the Seventh Circuit encourages litigation that might not otherwise occur:

The absence of definitive decision, equally binding on citizens wherever they may be, exacts a price whether or not a conflict ultimately develops. That price may be years of uncertainty and repetitive litigation, sometimes resulting from the unwillingness of a government agency to acquiesce in an unfavorable decision, sometimes from the desire of citizens to take advantage of the absence of a nationally-binding authoritative precedent.

“Federal attorneys,” says Howard, “regularly relitigate adverse decisions in other circuits” and hold that “adverse circuit rulings are not authoritative until three circuits concur” [27]. Moreover, litigants have been known to seek circuit conflict in the hopes of increasing the likelihood of Supreme Court review [5]. This lack of finality, or “persevering possibility of differences developing” creates legal uncertainty. Uncertainty—quite apart from the economic resources expended by litigants—taxes the already strained capacity of the federal courts “by a cyclical dynamic. Greater uncertainty breeds more litigation, more litigation breeds greater uncertainty” [28].

Unlike unfairness and nonacquiescence, inefficiency and uncertainty are less normatively-laden and more performance-oriented concerns. Each of the latter pair involve likely calculable costs—borne by economic actors or the federal courts themselves—that are higher relative to a circumstance in which circuit conflicts did not exist. They can be lumped together as suboptimization costs.

As with rule of law costs, each of the suboptimization costs are triggered under different circumstances. Inefficiency is triggered in any conflict centering on a rule that requires compliance by a multicircuit actor or in any conflict involving a multicircuit actor as a party. Uncertainty, on the other hand, is endemic in the system. The very potentiality of conflict creates some baseline level of uncertainty. However, for present purposes, we will narrow the specification of uncertainty to actual conflicts which prove persistent. Presumably, once a conflict is definitively resolved, the degree of uncertainty with respect to that legal issue recedes. Conversely, conflicts that remain active yet escape resolution fuel uncertainty and opportunistic litigation.

Table 1 depicts the two cost categories, their respective concerns, and the circumstances under which each concern is triggered.

Methods—How to Identify Conflicts

In this section, I detail the disadvantages of prior methods of identifying circuit conflicts, introduce a novel method of conflict identification relied upon for the present study, discuss the modes of conflict resolution, and specify the scope of inquiry—including the timeframe and legal subject areas examined.

Prior Attempts to Identify Conflicts

An intercircuit conflict is initiated whenever one circuit announces a ruling on the interpretation of a provision of federal law which is inconsistent with the prior ruling of at least one other circuit [5]. One important limitation of the literature is the way in which conflicts are identified. Most studies rely upon certiorari petitions or the Spaeth Supreme Court Database to identify conflicts [29]. Both sources can be problematic. Reliance on cert petitions excludes from view all conflicts in which Supreme Court review is not sought— these constitute a “hidden docket”. Hellman dismissed such cases, considering it “unlikely that the hidden docket… contains any substantial number of certworthy cases” [5]. But the hidden docket may contain a substantial number of conflicts in important areas of law. As Joseph F. Weis, chairman of the Federal Courts Study Committee, stated in 1991: "Many litigants do not have the economic incentive or reasonable expectation of securing certiorari that leads parties to bring a conflict to the attention of the Supreme Court, even though the intercircuit disagreement may have wide effect." Where the expected costs of continued litigation are great and the expected benefits are remote and speculative, many litigants may decline to seek certiorari, even where their case involves a circuit conflict. Whether individual litigants find it individually rational to pursue their case to the utmost is no certain gauge of whether such cases are, in the aggregate, systemically important. Thus, we cannot be sure how many splits exist or how tolerable they are if we ignore cases in which cert is not sought.

Reliance on the Spaeth Supreme Court Database is even more problematic for our purposes. The Database codes cases according to many factors, saving court scholars a great deal of labor. Scholars who use it to identify conflict cases generally rely on the “certReason” variable, which identifies cases in which the Supreme Court listed conflict as the reason for granting review. As Bruhl explains,

the Database’s “certReason” variable is coded in a precise, narrow way. Based on my observations of how the coding protocol is applied, the Database does not show a case as involving a split unless the Supreme Court describes that as the reason for granting certiorari, even when the Court reveals the division of authority near the mention of the grant. If the opinion of the Court says, “We granted certiorari in order to resolve a conflict in the circuits concerning X,” that will count… [29] But, as Bruhl goes on to catalogue, in many instances the Court does indicate the existence of conflict—though with superficial changes in phrasing or placement—and the database codes as “no reason given” [29]. In reliance on the Database, Lindquist and Klein [17] found that “conflict cases have made up about 30 percent of the Court's docket in recent years” [17]. Similarly, Bruhl [29] found that the “certReason” variable in the Database shows that an average of 32.63 percent of the Supreme Court’s docket during the 2010-2013 terms were split-related. But Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg reported in 2003 that “about 70 percent of the cases we agree to hear involve deep divisions of opinion among federal courts of appeals or state high courts” [30]. Hellman [31] found 68.7 percent during the 1993 1995 terms; Stras [32] found 59.8 percent during the 2003-2005 terms.

There are several caveats to note. First, while Hellman apparently read the cert grants himself, Justice Ginsburg and Stras’ methods of identifying the reason for cert are unclear. Second, neither Hellman, Justice Ginsburg, nor Stras limit their definition of conflict to intercircuit conflict, so their higher percentages may be somewhat inflated by an unknown number of state-court-only conflict cases. Third, some degree of variation can be expected from year to year. Nevertheless, the huge gap between the Database figures which hover around 30% and the substantially higher non-Database figures—taken together with Bruhl’s observation regarding the Database’s narrow coding—does suggest that the Database severely undercounts conflict cases on the Supreme Court’s docket.

In sum, reliance on cert petitions to identify conflict cases obscures from view conflicts in which cert is not sought by the litigants. The Spaeth Database, by coding only those cases in which cert was sought and granted, and by failing to identify all of those—is an even less appropriate tool for mapping the conflict landscape. We must have a better idea of how many splits are generated and how many persist before assessing the consequences of conflict on the system. The two most common methods cannot get us there.

A New Method for Identifying Conflicts

A more natural, though more time-intensive, method would be to look to circuit court opinions themselves. We can reasonably identify a conflict according to whether the system’s authorities consider their own work or the work of colleagues as constituting a conflict [3,8,18]. As a matter of convention, circuit court opinions tend to note when legal issues relevant to the case implicate a conflict among the circuits. While some conflicts may escape mention in some circuit court opinions, it seems unlikely given the ubiquity of the practice that many conflicts will go unremarked by all judges involved in all relevant cases. Conversely, some conflicts might be indicated which turn out, upon inspection, to be reconcilable. “Determining whether or not a conflict exists is often subjective” [33]. Yet judges themselves seem reluctant enough in declaring the existence of conflict that undercounting still seems the greater risk [5,33,34]. To preserve transparency and replicability, I adhere closely to the characterization of the controversy by the circuit judges themselves. A split is a split if the system’s authorities regard it so. This method, which requires careful attention to a voluminous body of circuit court opinions, would have been perhaps prohibitively time-consuming at the time of Hellman’s authoritative studies in the 1990’s. But two subsequent developments reduce the burden of this work. First, U.S. Law Week (USLW), a legal news periodical, began publishing a regular Circuit Splits Roundup in 1998 which reports on a monthly basis all conflicts noted in circuit court opinions and organizes them by legal subject area. This report provides a helpful starting point for the researcher wishing to stay abreast of conflict cases. Because the report is triggered by any mention of conflict in a circuit court opinion, it allows the researcher to capture not only splits initiated during a given reporting period, but also those initiated in prior periods yet which remain active, i.e., relevant to litigation in the period under observation. Thus, the roundup catalogues conflicts initiated since 1998 but also conflicts initiated in prior periods, but which remain active in later periods. Like Hellman [6], I assume that dormant (or inactive) conflicts do not contribute meaningfully to the costs I noted above, and my method necessarily excludes them. The second labor-saving development is the advent of legal research software produced by companies such as Westlaw and Lexis Nexis. Using cases identified in USLW as seeds, I turn to Westlaw’s embedded search tools to fully map all cases and circuits implicated in the conflict1.

Resolutions

Circuit conflicts can be resolved in at least three ways. Most obviously, the Supreme Court may review a case implicated in the split and authoritatively declare a single interpretation. As previously noted, the Supreme Court resolved virtually all lower court conflicts until at least the 1950’s [11]. In recent years, however, despite dedicating 30 to 70 percent of its annual docket to circuit conflict cases [29,30], the Court apparently leaves many conflicts unresolved [18,19]. Alternatively, the circuits themselves may ultimately converge on a single interpretation in subsequent decisions, or Congress may amend a statute in such a way as to render the conflict moot. Absent affirmative resolution via Supreme Court review, circuit convergence, or congressional action, changed circumstances may simply reduce or eliminate the significance of the underlying legal issue, leaving the conflict technically on the books while generating no additional litigation [6]. Thus, a conflict may technically persist but lay dormant. As indicated above, by focusing on references to circuit conflict in legal opinions, my approach necessarily excludes dormant conflicts. I regard a conflict as resolved in the event of Supreme Court review, circuit convergence, or congressional action that ends the controversy.

Scope of Inquiry

“In classifying conflicts,” says Hellman, “it is natural to begin by identifying the area of law in which the conflict has developed…” [5]. So too, it helps to specify an interval over which to begin the classification. To narrow the scope of inquiry to manageable proportions, I examine conflicts in four legal subject areas— employment discrimination, search and seizure, securities, and labor law—active during the interval 1998 to 2010. I trace the development of each conflict until the end of calendar year 2015.

Each legal subject area involves important questions of American law. Employment discrimination involves the interpretation of key provisions of statutes such as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA) in cases where plaintiff/employees seek remedies for alleged violations of such acts by defendant/employers. Labor law involves employees and employers as well but implicates broader national labor regulations such as those arising under the National Labor Relations Act and overseen by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Securities law typically involves disputes arising out of the enforcement of the Securities Exchange Act and related amendments as overseen by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Search and seizure law has its basis in the U.S. Constitution and involves the availability of the Fourth Amendment’s protection to criminal defendants against unreasonable searches and seizures.

Each legal subject area contributes to the consideration of costs. If what the law requires in any of these areas—e.g., what constitutes a reasonable accommodation for a disabled employee, the legality of a search, the mens rea required to establish liability for securities fraud, whether a worker of a given job description constitutes a protected non-supervisor—turns solely upon differences in the geography of the litigants, unfairness is implicated. Where a statutory scheme is overseen by a federal agency (e.g., SEC and NRLB) which must enforce different interpretations of the same legal provision or else acquiesce nationwide to only one circuit's view, agency nonacquiescence is implicated. Where the matter involves employers and employees (employment discrimination and labor law) or firms and investors (securities law) in the national economy, economic inefficiency is implicated. Where additional litigation may be generated in any of these legal subject areas due simply to the “persevering possibility of differences developing” [35], this uncertainty taxes the capacity of the federal court system.

Finally, the choice of conflicts arising under both statutory and constitutional law is intentional. To the extent that conflicts are a result of statutory ambiguity [36,37], greater care from Congress in legislative drafting could serve as a prophylactic, and greater congressional willingness to revise problematic statutes could serve as a remedy. Yet it is not only in “minutely particular federal statutes” [2] that conflicts arise. Some scholars have argued that conflicts are especially intolerable when they involve the assignment of constitutional rights [3,38]. Even some trivialists concede that “[v]aried interpretation of federal constitutional law raises different, and arguably more troubling, questions” [36]. Prior scholarship suggests that these conflicts emerge and persist due to a combination of opaque doctrinal guidance from the U.S. Supreme Court, ideological diversity among circuit judges, and delayed review by a Supreme Court that has become increasingly economical in its grants of certiorari [3,39,40]. With regard to the “grandly general mandates” articulated in the U.S. Constitution [2], it may be important to admit that no single, correct answer exists and the crucial thing is to settle the matter through clear, definitive, and speedy Supreme Court resolutions.

Data and Analysis

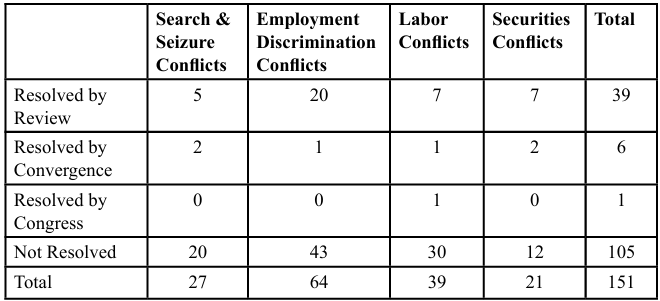

A total of 151 conflicts were identified across the four legal subject areas: 27 in search and seizure, 64 in employment discrimination, 39 in labor, and 21 in securities law. See Table 2.

Of the 27 search and seizure conflicts, 7 were resolved—5 by Supreme Court review and 2 by convergence of the circuits. Of the 64 employment discrimination conflicts, 21 were resolved—20 by Supreme Court review and 1 by convergence. Of the 39 labor conflicts, 9 were resolved—7 by Supreme Court review, 1 by convergence, and 1 by the revision of a statute by Congress. Finally, of the 21 securities conflicts, 9 were resolved—7 by Supreme Court review and 2 by convergence.

Though generated over a span of decades, each of these conflicts actively contributed to litigation and were referenced in circuit court opinions during the 1998-2010 observation period. Over half of the splits originated prior to 1998, with a few stretching back to the 1960’s and 70’s. Yet only 46—30 percent—were resolved by the end of calendar year 2015.

With the data in hand, three questions loom large in ascertaining the costliness of circuit conflict. First, how many conflicts persist, i.e., remain active yet unresolved? Second, how many of the persistent conflicts trigger precisionist concerns? Third, of those conflicts which persist and trigger precisionist concerns, how many present legally significant issues? Each of these questions is addressed in turn below.

How many conflicts persist?

Of the 151 conflicts active across the four legal subject areas during the 1998-2010 interval, 70 percent went unresolved by any of the three mechanisms as late as 2015. Because a substantial subset of the conflicts originated well before the 1998 beginning threshold, many of these conflicts persist much longer than the 18-year period implied by the 2015 cut-off. The average length of the unresolved conflicts is 20 years (median of 19 years), the longest being a labor law conflict reaching all the way back to 1962! That conflict—a dispute over whether the parol evidence rule is fully applicable to collective bargaining agreements—is a 7-1 split in which the Ninth Circuit is the lonely outlier. The Ninth Circuit, it should be noted, encompasses 9 states, several U.S. territories, and one-fifth of the American population. Such a longstanding conflict might be regarded as moot if not for the fact that it continues to be relied upon in circuit court opinions in the Ninth Circuit and referenced by its sister circuits throughout the observational window. The Sixth Circuit, in Brown- Graves Co. v. Central States, Southeast and Southwest Areas Pension Fund in 2000, was the last circuit to declare a position in the split.

Of the 46 conflicts that were resolved, 33 percent were resolved quickly (within 18 months of initiation), while 50 percent took 6 years or more, and 33 percent took ten years or more to reach resolution. Thus, consistent with Lindquist [41] and Beim and Rader [18], the courts appear to act immediately to resolve some conflicts, leave some to linger for years before resolution, and neglect most to linger indefinitely despite their ongoing relevance in subsequent litigation. These initial findings alone seriously undermine trivialist notions that conflicts are few in number or brief in duration. Rather they suggest a body of national law significantly fragmented across twelve appellate jurisdictions. On the other hand, many of these conflicts may disturb the legal landscape very little beyond that which is already tolerated in a system of common law adjudication. Thus, we turn to our second question.

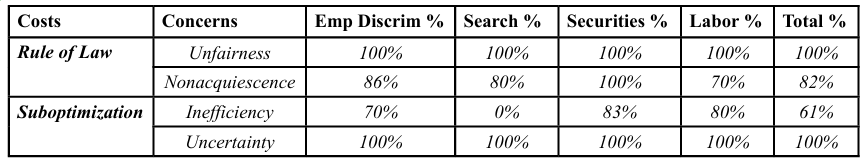

How many persistent conflicts trigger precisionist concerns?

Unfairness is triggered in any conflict that centers on a rule affecting the rights, duties, or liability of natural persons. In each of the four legal subject areas this turns out to be an easy criterion to satisfy. In employment discrimination, all of the unresolved conflicts involve natural persons seeking to vindicate statutory rights to nondiscrimination in employment. Similarly, in search and seizure, all of the unresolved conflicts involve natural persons seeking to vindicate a constitutional right against unreasonable search or seizure of person or property. In securities, all of the conflicts involve the rights, duties, or liability of natural persons under securities statutes or corresponding regulations. In labor, most of the conflicts center on broad labor policies between labor unions and corporate employers, decidedly not natural persons. Nonetheless, all of the unresolved conflicts involve the rights and duties of natural persons—either directly through individual employee suits or indirectly through labor policy controversies which determine the balance of rights and duties between workers and their employers. Hence, all 105 unresolved conflicts trigger the unfairness concern.

Nonacquiescence is triggered in any conflict that centers on a rule that depends for its application on the action of a federal agency. In unemployment discrimination, the EEOC is vital in screening claims, issuing right-to-sue letters, and pursuing litigation on behalf of claimants. Any conflict bearing upon an employee right, employer duty, or the prospects for a successful claim also constrains the EEOC’s execution of each of its functions. Thirty-seven of the 43 unresolved employment discrimination conflicts meet this description. In search and seizure, all of the conflicts involve constraints on law enforcement agencies relating to constitutional search and seizure protections for criminal suspects. Many of the cases involve alleged Fourth Amendment violations by state and local law enforcement agencies. But of course, the Fourth Amendment’s guarantees bind federal law enforcement agencies as well. Hence, either directly or indirectly, 16 of the 20 unresolved search and seizure conflicts trigger agency nonacquiescence concerns. The SEC enforces securities statutes and its own regulations promulgated under the authority of those statutes. The SEC also oversees non-governmental regulatory bodies such as the Federal Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA).

Each of the 12 unresolved securities conflicts center on rules that involve SEC oversight and trigger the nonacquiescence concern. Labor law is overseen by federal agencies such as the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and the National Mediation Board (NMB), and 21 of the 30 unresolved conflicts center on rules under their purview, triggering the nonacquiescence concern. Hence, 86 of the 105 unresolved conflicts trigger the nonacquiescence concern.

Inefficiency is triggered in any conflict centering on a rule requiring multicircuit actor compliance or involving a multicircuit actor as a party. In unemployment discrimination, 37 of the 43 unresolved conflicts meet this description; in search and seizure, none do. In securities, 10 of the 12 conflicts require compliance by multicircuit actors; in labor, that number is 24 of 30. Hence, 64 of the 105 conflicts trigger the inefficiency concern.

Uncertainty is triggered in any conflict that persists. Of course, all of the 105 unresolved conflicts meet this description. If we also count conflicts that persist for 10 or more years before resolution, the total number of conflicts contributing to uncertainty climbs to 120—80 percent of all conflicts. If we count all conflicts that took six or more years to reach resolution, the number climbs to 128—85 percent.

All of the unresolved conflicts suggest rule of law costs—with each triggering the unfairness concern and 82 percent triggering the nonacquiescence concern. Similarly, all of the unresolved conflicts suggest suboptimization costs—with each triggering the uncertainty concern and 61 percent triggering the inefficiency concern. See Table 3.

Of those persistent conflicts which trigger precisionist concerns, how many present legally significant issues?

Even if conflicts are not few in number or brief in duration, they may yet prove small in legal significance. The classification scheme employed above cannot, without more, tell us if the legal questions at the heart of each split is likely to significantly influence the behavior of legal actors in ways that instantiate the corresponding costs to any significant degree. “At one extreme,” writes Hellman, “are conflicts involving rules that directly regulate primary conduct” [5]. The types of questions that arise under such rules are most likely to influence the behavior of legal actors and instantiate corresponding costs because they are, by their very nature, outcome-determinative. For example, determining whether “a parent corporation [is] liable as an ‘owner or operator’ for environmental clean-up costs incurred by its wholly owned subsidiary” under the Superfund Act (CERCLA) will determine the outcome of litigation [5]. Any split involving such a question is likely to force agencies such as the EPA to choose between uniform administration and faithfulness to multiple juridical masters (nonacquiescence); require multicircuit actors to adapt their production practices, personnel management, training, etc. to different regulatory standards (inefficiency); and encourage strategic and repetitive litigation among litigants in search of a more favorable rule (uncertainty).

At “[t]he other end of the spectrum… are procedural rules… which govern the manner and means by which substantive rights are enforced” [5] and rules that contain “one or more indeterminate elements” [5]. Many procedural rules are addressed to judges alone and do not come into play until deep into litigation. But some procedural rules shift the balance between the parties in clear and foreseeable ways, including rules that impact the tolling of limitations periods, the admissibility of certain types of evidence, the availability of presumptions in favor of one party rather than another, and the operation of affirmative defenses. Hence, even procedural rules will have a significant impact on fairness to and the behavior of legal actors to the extent that they impose systematic bias in favor of one class of litigant over another.

Indeterminate rules are more difficult to classify a priori, and their classification is therefore inherently more subjective. Such rules naturally exist on a spectrum and, as Hellman observed, the less determinate a rule the more likely it is to invite as much variation within a circuit as between circuits [5]. For present purposes, where a conflict involves gradual shadings on a rule so fine “that the result in any given case will depend on the facts and the predilections of the particular panel rather than on the articulated rule” [5], I set it aside. I do so on the rationale that the variation observed in such conflicts fails to rise above the baseline variation inherent in common law adjudication. Thus, I regard a conflict as legally significant if the answer to the legal question at the heart of the split:

a. Is outcome-determinative, or

b. Imposes systematic bias in favor of one class of litigant over another.

Unresolved conflicts that satisfy neither condition may be regarded as trivial. For example, a conflict over whether the Equal Opportunity Commission may issue a right-to-sue letter before the expiration of a 180-day conciliation period—the Ninth, Eleventh, and Tenth Circuit said yes; the Twelfth Circuit said no—affects precisely how quickly complainants may file suit but not whether they may file or their likelihood of prevailing2. Such an issue may be regarded as trivial. On the other hand, whether a plaintiff alleging fraud under the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act must prove scienter with respect to each defendant or may rely on a broad theory of collective scienter is more consequential. While the choice of legal standard alone is not outcome-determinative, the Seventh, Second, and Sixth Circuit’s adherence to a collective scienter standard certainly improves a plaintiff’s chances of prevailing relative to the Fifth and Eleventh Circuit’s individual scienter standard3. Moreover, whether an employer’s liability for violations of the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act is measured in working days or calendar days is outcome-determinative in one important sense. The amount of damages an employee is entitled to is higher in the Third Circuit (calendar day rule) than in the Fifth, Tenth, Sixth, Eighth, and Ninth Circuits (working day rule) for no other reason than the legal standard is different4.

Of the conflicts which were not resolved, 61 percent trigger precisionist concerns and qualify as legally significant5. Of all 151 of the conflicts identified in this study, 42 percent can be classified as persistent (i.e., active and unresolved), relevant to precisionist concerns, and legally significant.

Discussion

There are several important implications of these findings. First, the Supreme Court’s early rationale for permitting the decisional independence of the regional circuits balanced the value of error spotting against the temporary costs of disharmony which were to be endured only “until a higher court has settled the law” (Mast, Foos & Co. v. Stover Manufacturing Co., 177 U.S. 485, 488-489 (1900)). Yet, consistent with Beim and Rader [18], I find that 70 percent of conflicts are never resolved, suggesting that the costs of conflict are greater today and “changed circumstances have led to an alarming number of intolerable circuit splits” [42]. Moreover, recent studies have highlighted patterns of conflict initiation among the circuits [14,16] and patterns of resolution by the Supreme Court [3] that suggest the value of conflict as a form of error-spotting may be greatly overestimated.

Second, trivialists generally assume that circuit conflicts are few in number, brief in duration, and/or small in legal significance [6,36]. Yet, 42 percent of the 151 conflicts identified in this study were unresolved and could not be dismissed as legally insignificant— undermining trivialist assumptions.

Third, all of the unresolved conflicts (and even many conflicts that were ultimately resolved) triggered rule of law and suboptimization costs. Taken together, these findings validate precisionist concerns about regional variation of federal law while undermining trivialist assumptions and raising considerable doubt regarding percolationist assumptions.

Fourth, the prevalence of conflicts arising under statutory schemes does suggest that many conflicts could be avoided by more careful legislative drafting and resolved by a Congress more willing to revise problematic statutory provisions. But in many instances, it was murky Supreme Court precedent regarding the interpretation of statutory provisions that drove disagreement among the circuits. Moreover, in Fourth Amendment jurisprudence, opaque guidance from the Supreme Court tells the whole story. The etiology of the conflicts identified here is worthy of its own study.

There are several limitations to note. First, at present, it is unclear how to generalize from the 151 conflict observations gathered here to the greater universe of circuit splits. U.S. Law Week—the source of my seed cases—classifies conflicts according to the legal subject area implicated in the split, even if the cases constituting the split revolve mostly around other legal issues. Judicial caseload statistics, such as those gathered by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, typically classify cases according to the legal subject that predominates in each case. Therefore, the most straightforward way of generalizing from the conflicts in my data to the greater universe of federal court cases appears unavailable.

Second, I have admittedly used the term “cost” rather loosely. In the case of the normative concerns which I label rule of law costs, this conceit is excusable. However, the performance- oriented concerns which I label suboptimization costs are potentially calculable. These should be measured, even if measuring them lay beyond the scope of this effort. At the very least, unsettled questions of law invite parties—uncertain of their rights and duties—to allocate scarce individual resources to settle the matter in court, produces costly delay for all litigants as dockets become clogged, and triggers the allocation of additional institutional resources by the federal courts to meet the demands of litigants. This matter too is worthy of additional study.

Conclusion

The organ of national government responsible for resolving disputes over the meaning and application of national law frequently produces non-uniform interpretations of national law through the issuance of conflicting holdings by the circuit courts of appeals, the intermediate tier of its three-tiered hierarchy. High caseloads, limited Supreme Court review, and the absence of a formal consensus mechanism across regional appellate jurisdictions make occasional disagreement inevitable and long-enduring. Despite the speculative benefits of regional variation, there are certain costs—including the propensity to cause unfairness to litigants, nonacquiescence among federal agencies to conflicting authority, economic harms to multicircuit actors, and repetitive litigation from litigants seeking to initiate or exploit circuit conflict. Overall, I find that a substantial number of legally significant conflicts persist indefinitely, validating the concerns of critics. More study is needed to determine the net impact of this phenomenon on the fairness and efficiency of the judicial system.

Competing Interest:

The authors of this research declare no competing interest regarding this study.

References

Shauku, A. K. (2020). Institutional entrepreneurship and evolution: Making sense of the american judiciary. In D. J. D’Amico, & A. G. Martin (Eds.), Philosophy, politics, and austrian economics (advances in austrian economics, vol. 25) (pp. 191–208) Emerald Publishing Limited. View

Ginsburg, R. B., & Huber, P. W. (1987). The intercircuit committee. Harvard Law Review, 100(6), 1417–1435. View

Logan, W. A. (2012). Constitutional cacophony: Federal circuit splits and the fourth amendment. Vanderbilt Law Review, 65(5), 1137–1203. View

Krotoszynski, R. J. (2014). The unitary executive and the plural judiciary: On the potential virtues of decentralized judicial power. Notre Dame Law Review, 89(3), 1021–1084. View

Hellman, A. D. (1995). By precedent unbound: The nature and extent of unresolved intercircuit conflicts. University of Pittsburgh Law Review, 56, 693–800. View

Hellman, A. D. (1998). Light on a darkling plain: Intercircuit conflicts in the perspective of time and experience. The Supreme Court Law Review, 1998, 247–302. View

Ulmer, S. S. (1984). The supreme court's certiorari decisions: Conflict as a predictive variable. The American Political Science Review, 78(4), 901–911. View

Shauku, A. K. (2018). Twelve sisters: The U.S. federal courts, regional independence, and the rule of law(s) (PhD). View

Miner, R. J. (1993). Federal court reform should start at the top. Judicature, 77(2), 104–108. View

Strauss, P. L. (1987). One hundred fifty cases per year: Some implications of the supreme court's limited resources for judicial review. Columbia Law Review, 87(6), 1093–1136. View

Algero, M. G. (2003). A step in the right direction: Reducing intercircuit conflict by strengthening the value of federal appellate court decisions. Tennessee Law Review, 70, 605–641.

Beim, D. (2017). Learning in the judicial hierarchy. The Journal of Politics, 79(2), 591–604. doi:10.1086/688442 View

Clark, T. S., & Kastellec, J. P. (2013). The supreme court and percolation in the lower courts: An optimal stopping model. The Journal of Politics, 75(1), 150–168. View

Coenen, M., & Davis, S. (2021). Percolation's value. Stanford Law Review, 73, 363–432. View

Dragich, M. J. (2010). Uniformity, inferiority, and the law of the circuit doctrine. Loyola Law Review, 56, 535–590. View

Epps, D., & Ortman, W. (2018). The lottery docket. Michigan Law Review, 116(5). View

Lindquist, S. A., & Klein, D. (2006). The influence of jurisprudential considerations on supreme court decisionmaking: A study of conflict cases. Law & Society Review, 40(1), 135 161.View

Beim, D., & Rader, K. (2019). Legal uniformity in american courts. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 16(3), 448–478. View

Miner, R. J. (2013). "Dealing with the appellate caseload crisis": The report of the federal courts study committee revisited. New York Law School Law Review, 57, 517–554. View

Beim, D., & Rader, K. (2016). Evolution of conflict in the courts of appeals. Unpublished manuscript. Retrieved 10/18/2017. View

Beim, D., & Rader, K. (2021). Ideology, certiorari, and the development of doctrine in the U.S. courts of appeals. Unpublished manuscript. View

Black, R. C., & Owens, R. J. (2009). Agenda setting in the supreme court: The collision of policy and jurisprudence. The Journal of Politics, 71(3), 1062–1075. View

Koh, S., Y. (1991). Nonacquiescence in immigration decisions of the U.S. courts of appeals. Yale Law & Policy Review, 9(2), 430–454. View

Meador, D. J. (1989). A challenge to judicial architecture: Modifying the regional design of the U.S. courts of appeals. The University of Chicago Law Review, 56(2), 603–642. View

Wallach, L. R. (1986). Intercircuit conflicts and the enforcement of extracircuit judgments. Yale Law Journal, 95(7), 1500–1521. View

Carrington, P. D., & Orchard, P. (2010). The federal circuit: A model for reform? The George Washington Law Review, 78(3), 575–585.View

Howard, J. W. (1981). Courts of appeals in the federal judicial system: A study of the second, fifth, and district of columbia circuits. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. View

Tiberi, T. J. (1993). Supreme court denials of certiorari in conflicts cases: Percolation or procrastination? University of Pittsburgh Law Review, 54, 861–891.

Bruhl, A. (2014). Measuring circuit splits: A cautionary note. Journal of Legal Metrics, 3(3), 361–383. View

Ginsburg, R. B. (2003). Workways of the supreme court. Thomas Jefferson Law Review, 25, 517–528.

Hellman, A. D. (1996). The shrunken docket of the rehnquist court. The Supreme Court Law Review, 1996, 403–438. View

Stras, D. R. (2007). The supreme court’s gatekeepers: The role of law clerks in the certiorari process. Texas Law Review, 85, 947–997. View

Perry, H. W. (1991). Deciding to decide: Agenda setting in the united states supreme court. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. View

Wasby, S. L. (2002). Intercircuit conflicts in the courts of appeals. Montana Law Review, 63, 119–196. View

Commission on Revision of the Federal Court Appellate System. (1975). Structure and internal procedures : Recommendations for change : A preliminary report / commission on revision of the federal court appellate system. District of Columbia: The Commission, 1975. View

Frost, A. (2008). Overvaluing uniformity. Virginia Law Review, 94(7), 1567–1639. View

Smith, J. W. (2011). Evidence of ambiguity: The effect of circuit splits on the interpretation of federal criminal law. Suffolk Journal of Trial and Appellate Advocacy, 16(1), 79–96. View

Rehnquist, H. W. (1986). The Changing Role of the Supreme Court, 14 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 1. View

Klein, D. (2002). Making law in the united states courts of appeals. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. View

Songer, D., Sheehan, R. S., & Haire, S. B. (2000). Continuity and change on the united states courts of appeals University of Michigan Press. View

Lindquist, S. A. (2000). The judiciary as organized hierarchy: InterCircuit conflicts in the federal appellate courts. Unpublished manuscript.

Menell, P. S., & Vacca, R. (2020). Revisiting and confronting the federal judiciary capacity "crisis": Charting a path for federal judicial reform. California Law Review, 108, 789–886. View