Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices Volume 4 (2020), Article ID: JPHIP-166

https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100166Review Article

Parental Monitoring of Academics and Adolescents’ Engagement in Substance Use

Debadutta Goswami1, Kip R. Thompson, PhD2*

Master of Public Health Program, Missouri State University, Springfield, MO, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Kip R. Thompson, PhD, Assistant Professor, Master of Public Health Program, Missouri State University, Springfield, MO, USA. E-mail: kiprthompson@missouristate.edu

Received date: 24th April, 2020

Accepted date: 29th May, 2020

Published date: 01st June, 2020

Citation: Goswami, D., & Thompson, K.R. (2020). Parental Monitoring of Academics and Adolescents’ Engagement in Substance Use. J Pub Health Issue Pract 4(1):166.

Copyright: ©2020, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Lifelong substance use often begins during adolesence. Eightyeight percent of adult daily smokers began before age 18. By 12th grade, about two-thirds of student have tried alcohol; approximately half of 9th through 12th grade students have reported ever having used marijuana; and among 12th graders, approximately 2 in 10 reported using prescription medicine without a prescription. Adolescents reporting lower levels of parental monitoring are more likely to use illicit substance (primarily cannabis use). Poor parental monitoring is associated with many negative youth outcomes, including maladjustment, association with deviant peers, and poor performance in school. The purpose of this research was to determine if parental involvement in student academics, specifically parental checking student homework and parental help with student homework, were significantly associated with substance use based on data from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). The results of this study indicate both parental checking of homework and helping with homework are strongly and significantly associated with a reduction in substance use by adolescents (p = 0.0001).

Introduction

Adolescence is a vulnerable period when people are particularly sensitive to substance use. Lifelong substance use often begins during this stage of life. Eighty-eight percent of adult daily smokers began before age 18. By 12th grade, about two-thirds of student have tried alcohol; approximately half of 9th through 12th grade students have reported ever having used marijuana; and among 12th graders, approximately 2 in 10 reported using prescription medicine without a prescription [1]. Substance use can have large impacts on health and well-being, causing avoidable illness and death. Substance use affects the growth and brain development of teens, risk factors to the development of adult health problems, such as heart disease and sleep disorders and may act as the driving force to adopt other risky behaviors, such as unprotected sex, violence and dangerous driving. Also, substance use may cause different kinds of cancers. Smoking tobacco causes lung, liver, and colorectal cancers; moderate to heavy alcohol consumption is associated with oropharyngeal, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers; associations between marijuana use and prostate and cervical cancer have also been observed [2]. Young adolescents are highly likely to be exposed to drug paraphernalia and offers to use drugs, especially alcohol and tobacco [3]. Monitoring adolescent substance use, however, is challenging [2]. Adolescents reporting lower levels of parental monitoring are more likely to use illicit substances (primarily cannabis use) [4]. Poor parental monitoring is associated with many negative youth outcomes, including maladjustment, association with deviant peers, and poor performance in school [5]. Parental monitoring and the engagement of parents in their children’s school life is one of the most important protective factors contributing to better student behavior, higher academic achievement and more likely adolescents will avoid unhealthy behaviors, such as substance use [6,7]. Children seek greater independence during adolescence and this can bring opportunities for engaging in unhealthy or unsafe behaviors [8]. Because of this, consistent parental monitoring becomes very critical. It is believed that adolescence is a time where there are expected conflict between parents and children, mostly disagreeing on clothing choice, but agree on more important issues, such as safety and morality. This research suggests that the understanding between parents and adolescents on safety issues is important in understanding the influence parents have on an adolescent’s choice of substance use [9]. Homework is one of the most popular and frequent instructional tools adopted by schools and used in home-based involvement. Through homework, parents are involved more directly in their child’s learning [10]. Substance use risk perceptions are higher among adolescents those who participated in school activities and received greater recognition from parents [11]

Research Question

There is very limited research on parental monitoring in terms of academic help and adolescents use of substance use. Previous studies have been conducted regarding school-based interventions by informing parents about their child’s effort in school and found that doing so improved grades and test scores and parental monitoring in terms of different variables like parental belief [12], parental behavior [13], parental warmth and support for homeschoolers [14]. Low parental warmth is linked to adolescents’ inability to express positive emotions effectively, and emotional distress [5]. Additionally, some research has shown that a parent’s involvement in homework is a positive practice which promotes academic achievement of their children, while other research describes this support as time consuming and generates discomfort, anxiety, and conflict in the family over homework [10]. However, no research to date has been conducted on whether parental involvement in academics, by homework checking and helping, may reduce substance use among adolescents. This lack of knowledge on the impacts of parental involvement in the reduction of substance abuse led the authors to ask: “Does Parental monitoring of academics (parents check if homework is done and parents help with homework) reduce adolescents’ engagement in substance use”. It is hypothesized that an association will exist between parental involvement in homework (checking or helping with homework) and substance use by adolescents.

Materials and Methods

The dataset used for analysis was derived from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration (SAMHSA) [15]. The dataset provides information on substance use and mental health data analyses and the use of illegal drugs, prescription drugs, alcohol, and tobacco. The data in the survey are collected through face-to-face interviews from US civilians older than 12 years of age and not institutionalized. The survey does not include homeless or those using shelters, military personnel on active duty, jails and hospitals. Data for the age group 12 to 17 years was used for analysis, which comprised 25% of the total data collected in 2018. The data was collected at the national, state and sub-state levels. It was a cross-sectional survey of 56313 respondents and contains 2691 variables. The questionnaire contains information on demographics, substance use, health, drug treatment, education, employment, health insurance, household roster, income, parenting experiences (parents of 12-17 years old) etc. The survey was conducted using Computer Assisted Interviewing (CAI) methods. The answers were gathered using ACASI (audio computer-assisted self-interviewing for sensitive questions), in which the respondents listened to prerecorded questions through headphones & entered responses into a NSDUH laptop, and CAPI (computer-assisted personal interviewing), in which the field interviewer (FI) reads questions and records responses. For all participants, a $30 cash incentive was given to those who completed the full interview. For the present study, the variables used for analysis were: Illicit drug, tobacco product, or alcohol-ever used, if parents checked on homework in the past year, and if parents helped with homework in the past year. Substance use among participants was assessed using the standard question “Illicit drug, tobacco product, or alcohol- ever used”. Participants responded 0, if no and 1, if yes. Homework checked or helped by parents was assessed using standard questions for children age 12 to 17 years. The questions were parents check if homework done in the past year and parents help with homework in the past year. Participants response to both the questions were recorded as 1, if always/sometimes and 2, if seldom/ never. To determine the associations between parental monitoring of academics (parents check if homework is done and parents help with homework) and adolescents’ engagement in substance use (illicit drug, tobacco, or alcohol) among adolescents’ age 12 to 17 years, a chi-square (χ2) statistic (α=0.05) was used. Concurrent to chi-square analyses, odds ratios were calculated for the association between parental engagement (exposure) and substance use (outcome). A Cramer’s V to analyze the strength of association between variables was also used. Data were analyzed using SPSS (standard v26).

Results

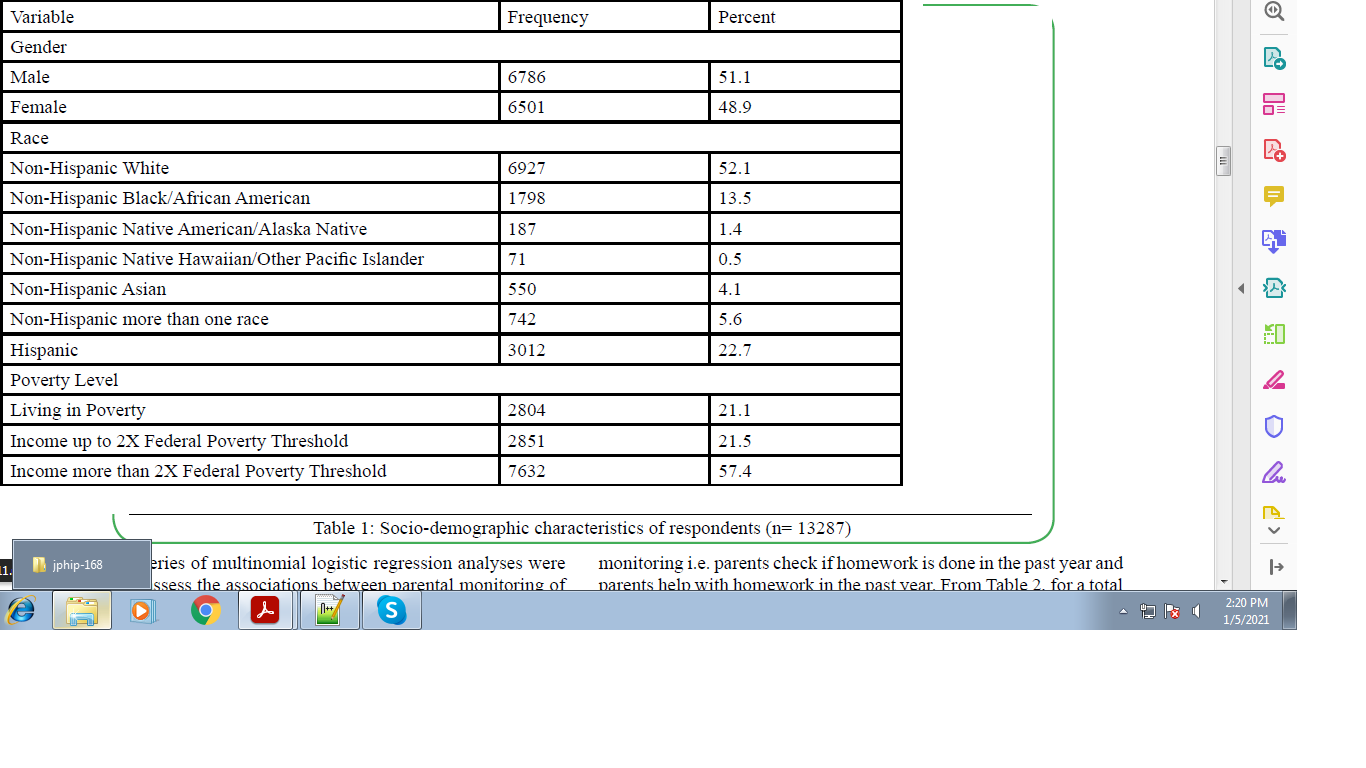

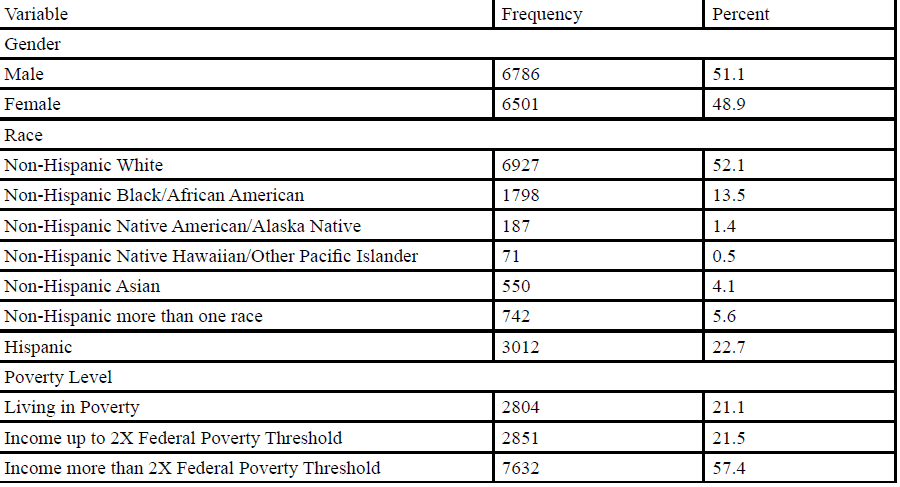

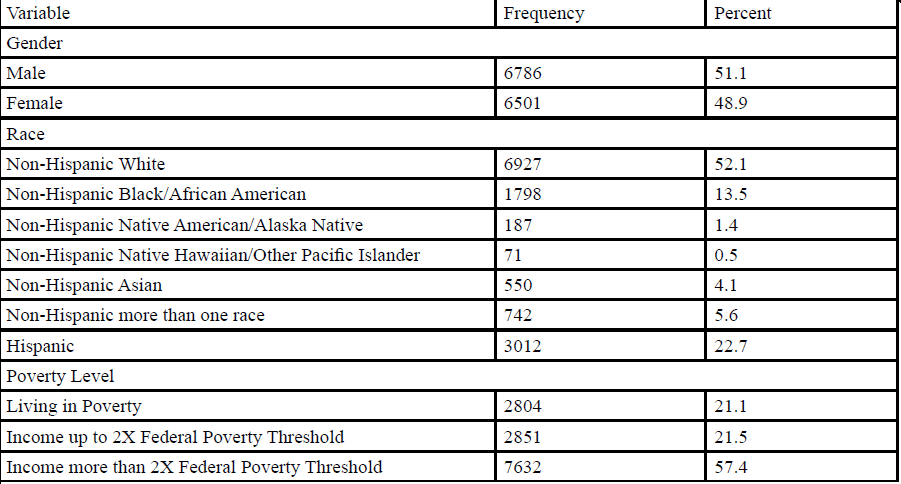

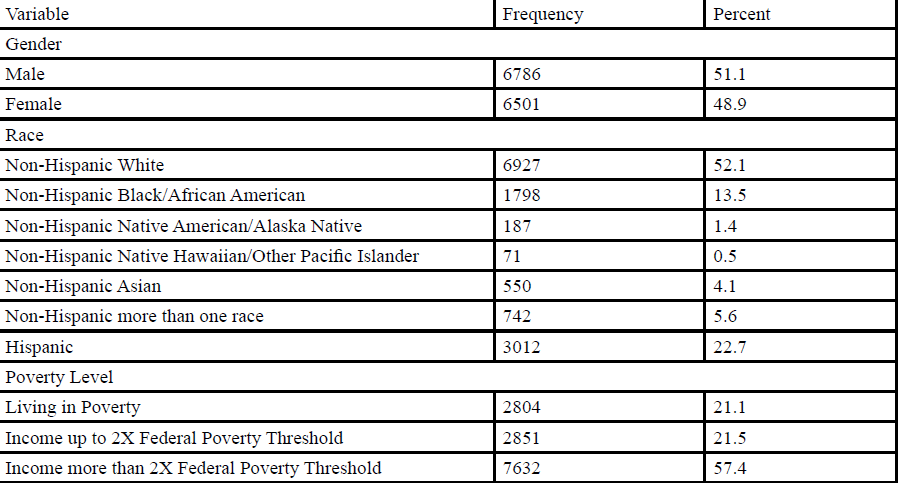

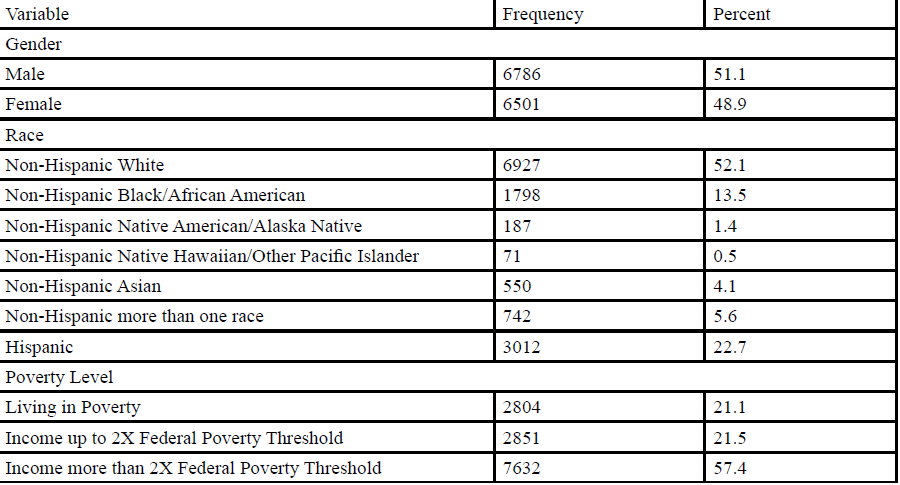

Table. 1 shows the general characteristics of the population who participated in the survey and selected for analyses purpose. A total of 13287 children of the age group 12 to 17 years were selected for the study. Of those selected 51.1% were male and 48.9% female. The majority were Non-Hispanic White (52.1%), followed by Hispanics (22.7%), and Non-Hispanic Black African/American (13.5%). Additionally, 21.1% of the population were living in poverty. Poverty was defined based on U.S. Census Bureau thresholds for each combination of family size and the number of children in the household. Living in poverty indicates having a family income less than the poverty threshold. A poverty level greater than 100% indicates having a family income greater than the poverty threshold [15].

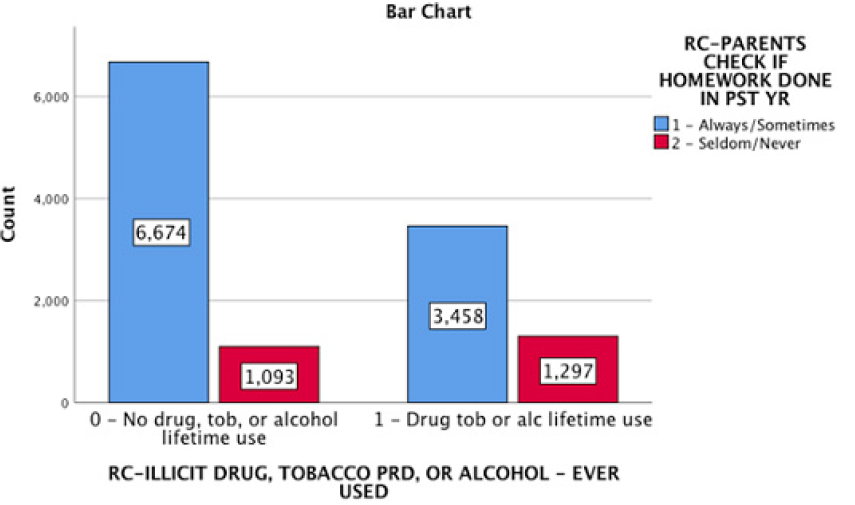

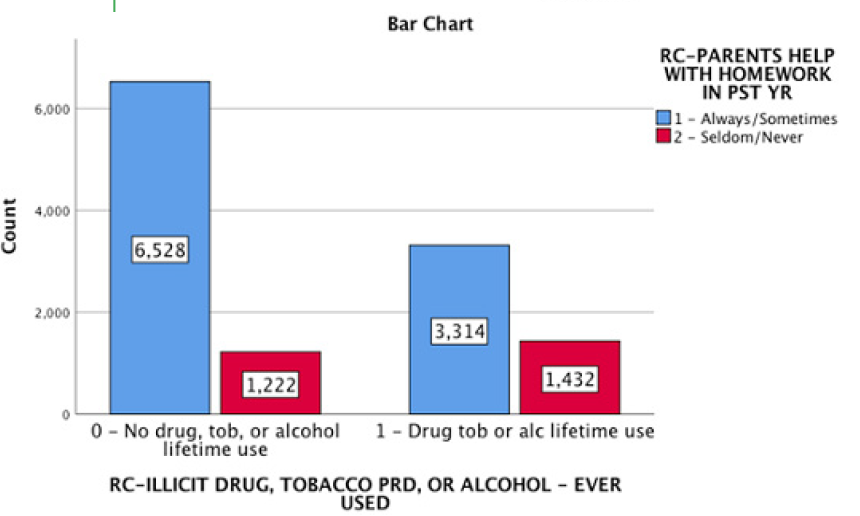

Initially, a series of multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess the associations between parental monitoring of academics and substance use among adolescents age 12-17 years, adjusting for the confounders such as gender, race and poverty level. Based on the results of these analyses, there was no significant effect of gender, race, and poverty level (alpha = 0.05 for all analyses). Because of no significant effects of potential confounders, associations between parental monitoring and substance use among adolescents age 12 to 17 years was conducted using the Chi-Square statistic. The statistical test was run for two indicators for parental monitoring i.e. parents check if homework is done in the past year and parents help with homework in the past year. From Table 2, for a total of 12522 children, we found that for those children who did not use substances, 85.9% (parents checked HW) and 84.2% (parents helped with HW) reported parental involvement in homework as always/ sometimes while 14.1% (parents checked HW) and 15.8% (parents helped with HW) reported seldom/never. For children who did use substances, only 72.7% (parents checked HW) and 69.8% (parents helped with HW) reported parental involvement in homework as always/sometimes while 27.3% (parents checked HW) and 30.2% (parents helped with HW) reported seldom/never (Figure 1).

Results of Chi-Square analyses are presented in Table 3, confirming a statistically significant (p < 0.0001) association between parental checking of homework and substance use. The results of the Phi and Cramer’s V tests resulted in a value of 0.163, indicated a strong association1. Calculated odds ratios for substance use were 0.70 (95%CI 0.67 - .73) for children whose parents check homework and 1.59 (95% CI 1.52 - 1.66) for children whose parents did not check homework. These results indicate a protective effect against substance use when parents engaged their children by checking homework. Additionally, children whose parents did not check homework were 59% more likely to use substances compared to those whose parents did check their homework.

We also examined if parents help in the homework is associated with substance use. From Table 4, a total of 12,496 children were included. Results indicated that children did not use drug, tobacco, or alcohol when 84.2% of parents always/sometimes helped with homework, whereas children used drug, tobacco, or alcohol when 69.8% of parents seldom/never helped with homework. Figure 2 depicts the substance use status of children for the variable parents help with homework in the past year.

Results of Chi-Square analyses are presented in table 5. The analyses indicated that there is a statistically significant association (p = 0.0001) between parental checking of homework and adolescent substance abuse. Based on subsequent Phi and Cramer’s V tests, the association was found to be strong (0.171) [16]. Calculated odds ratio for substance use were 0.69 (95% CI 0.66 - .72) for children whose parents helped with homework and 1.60 (95% CI 1.53 - 1.68) for children whose parents did not help with homework. These results indicate a protective effect against substance use when parents engaged their children by helping with homework. Additionally, children whose parents did not help with homework were 60% more likely to use substances compared to those whose parents did help with homework.

Discussion

The current study is one of the few studies that looked at the relationship between substance use (illicit drug, tobacco, or alcohol) among adolescents’ age 12 to 17 years and parental monitoring in terms of checking and helping children with homework. Parents interactions on homework with children was significantly associated with substance use behavior, specifically a reduction in substance use. A possible explanation may be that academically unsupervised adolescents may have more opportunities and time to experiment with substance use when they are not under the watchful eyes of their parents/guardians. The findings in this study are consistent with previous research showing that unsupervised adolescents are more likely to be involved in risky health behavior like substance use [17]. In a longitudinal study carried out in 4 public middle schools in Los Angeles, California, found that providing actionable information to parents about their child’s academic performance reduced adolescents’ engagement in substance use [7]. The study could not disentangle the effects of race on the association between parental academics monitoring and adolescents’ substance use. Prior studies have indicated that children aged 12-17 years with less parental involvement in academics (helping with homework) are more likely to skip school (high level skippers) and exhibits substance use behavior, and Hispanic youth were more likely to report truancy [18]. It is evident from previous studies that parental monitoring and substance use outcomes include individuals from various racial/ethnic groups[4]. The current study allowed for the exploration of potential determinants of the association between parental academics monitoring and substance use. The study used collapsed race measures to facilitate multivariate statistics, allowing the study to examine differences of parental academic monitoring and adolescents’ engagement in substance use across groups of respondents. The findings from the present study point to a relationship between race groups and adolescents’ substance use, there were no significant effects and the inclusion of race did not affect the overall outcome of parental academics monitoring. The findings also shed light on the importance of race-related factors as potential moderators. Previous studies suggested that there is a relationship between nativity and externalizing behaviors such as crime, violence, and drug misuse among adolescents in the U.S. One study ascertained that immigrants are less likely than their U.S. born adolescent counterparts to report involvement in a variety of externalizing behaviors [19]. Research has shown that higher hours of work are associated with a variety of problems, ranging from poor academic performance to substance use and varies by racial/ ethnic minority students [20]. The association between intensive work and substance use are significantly weaker for Hispanics and African Americans compared to Asian Americans and Whites [20]. We observed that adolescents who reported having monitored (homework checked or helped) by their parents were less likely to report ever using an illicit drug, tobacco products, or alcohol. In the future, it would be worth determining if there is an association between grades or test results and substance-use among adolescents. Future research should also examine causal explanations of race subgroup differences to inform the development of group-specific interventions. Also, future studies should examine the underlying familial and peer’ factors that may influence children’s substance use practices. Some studies assumed that association with deviant peers and delinquent behavior is more important for adolescent substance use outcomes than a general parenting style [21]. Future study variables should include information on parental monitoring outside school performance. Studies should be conducted to determine whether parental monitoring reduces substance use among late adolescents' age or younger age, because substance use increases greatly during late adolescence [7].

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests:

Authors report no conflict or competing interest.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Teen Substance Use & Risks.

Moss JL, Liu B, Zhu L. (2018). State Prevalence and Ranks of Adolescent Substance Use: Implications for Cancer Prevention. Prev Chronic Dis, 15:170345. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/ pcd15.170345View

Chan, G. C., Kelly, A. B., Carroll, A., & Williams, J. W. (2017). Peer drug use and adolescent polysubstance use: Do parenting and school factors moderate this association?. Addictive behaviors, 64, 78–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. addbeh.2016.08.004View

Blustein, E. C., Munn-Chernoff, M. A., Grant, J. D., Sartor, C. E., Waldron, M., Bucholz, K. K., Madden, P. A., & Heath, A. C. (2015). The Association of Low Parental Monitoring With Early Substance Use in European American and African American Adolescent Girls. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs, 76(6), 852–861. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2015.76.852View

Donaldson, C. D., Nakawaki, B., & Crano, W. D. (2015). Variations in parental monitoring and predictions of adolescent prescription opioid and stimulant misuse. Addictive behaviors, 45, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.01.022View

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parent Engagement in Schools.

Bergman P, Dudovitz RN, Dosanjh KK, & Wong MD.2019. Engaging Parents to Prevent Adolescent Substance Use: A Randomized Controlled Trial. AJPH October 2019, Vol 109, No. 10.View

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adolescent and School Health.

Sellers CM, McManama O’Brien KH, Hernandez L, & Spirito A. Adolescent Alcohol Use: The Effects of Parental Knowledge, Peer Substance Use, & Peer Tolerance of Use. Journal of the Society for Social Work & Research. 2018 Spring:9(1):69-87.View

Cunha J, Rosario P, Macedo L, Nunes AR, Fuentes S, Pinto R, & Suarez N. Parents’ conceptions of their homework involvement in elementary school. Psicothema. 2015;27(2):159-65.View

Denham B. E. (2014). Adolescent perceptions of alcohol risk: variation by sex, race, student activity levels and parental communication. Journal of ethnicity in substance abuse, 13(4), 385–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2014.958638 View

Mak H. W. (2018). Parental belief and adolescent smoking and drinking behaviors: A propensity score matching study. Addictive behaviors reports, 8, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. abrep.2018.04.003 View

Curtis, B., Ashford, R., Rosenbach, S., Stern, M., & Kirby, K. (2019). Parental Identification and Response to Adolescent Substance Use and Substance Use Disorders. Drugs (Abingdon, England), 26(2), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2 017.1383973View

Hodge, D. R., Salas-Wright, C. P., & Vaughn, M. G. (2017). Behavioral Risk Profiles of Homeschooled Adolescents in the United States: A Nationally Representative Examination of Substance Use Related Outcomes. Substance use & misuse, 52(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2016.12250 94View

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

Akoglu H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turkish journal of emergency medicine. 2018 August 7;18(3):91-93.View

Odukoya OO, Sobande OO, Adeniran A, Adesokan A. Parental monitoring and substance use among youths: A survey of high school adolescents in Lagos State, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2018;21:1468-75.View

Vaughn, M. G., Maynard, B. R., Salas-Wright, C. P., Perron, B. E., & Abdon, A. (2013). Prevalence and correlates of truancy in the US: results from a national sample. Journal of adolescence, 36(4), 767–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. adolescence.2013.03.015View

Salas-Wright, C. P., Vaughn, M. G., Schwartz, S. J., & Córdova, D. (2016). An "immigrant paradox" for adolescent externalizing behavior? Evidence from a national sample. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 51(1), 27–37. https://doi. org/10.1007/s00127-015-1115-1View

Bachman, J. G., Staff, J., O'Malley, P. M., & Freedman-Doan, P. (2013). Adolescent work intensity, school performance, and substance use: links vary by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Developmental psychology, 49(11), 2125–2134. https:// doi.org/10.1037/a0031464View

Berge J, Sundell K, Ojehagen A, & Hakansson A. Role of parenting styles in adolescent substance use: results from a Swedish longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016 Jan 14;6(1):e008979.View