Journal of Rehabilitation Practices and Research Volume 5 (2024), Article ID: JRPR-149

https://doi.org/10.33790/jrpr1100149Research Article

Occupational Therapy and Cancer: Perspectives of Patients and Health Care Providers

Marisa Monbrod, OTD, OTR/L, Yaseena Gurra, OTD, OTR/L, Connor Graves, OTD, OTR/L, Krimaben Mehta, OTD, OTR/L, & Lisa Jean Knecht-Sabres, DHS, OTR/L*

Department of Occupational Therapy, Midwestern University, USA.

Corresponding Author Details: Lisa Jean Knecht-Sabres, DHS, OTR/L, Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy, Midwestern University, USA.

Received date: 07th May, 2024

Accepted date: 21st June, 2024

Published date: 24th June, 2024

Citation: Monbrod, M., Gurra, Y., Graves, C., Mehta, K., & Knecht-Sabres, L. J., (2024). Occupational Therapy and Cancer: Perspectives of Patients and Health Care Providers. J Rehab Pract Res, 5(1):149.

Copyright:©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Background: This mixed method study investigated how cancer impacts the everyday life of cancer survivors from both the perspective of the cancer survivor and physicians. This study also explored factors which may be interfering with the physician’s ability to address the everyday needs of cancer survivors and refer their patients to occupational therapy.

Methods: This study used a sequential explanatory mixed methods design. RedCap electronic surveys were utilized to collect data from both cancer survivors (n=35) and physicians (n=13). To gather a deeper understanding, semi-structured focus groups (n=2) and interviews (n=3) were conducted to gather qualitative information from both cancer survivors (n=10) and physicians (n=2). Quantitative data were analyzed via descriptive statistics. Qualitative data were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed thematically. Results across data were compared to identify patterns. Rigor was enhanced by multiple coders, expert review, and triangulation.

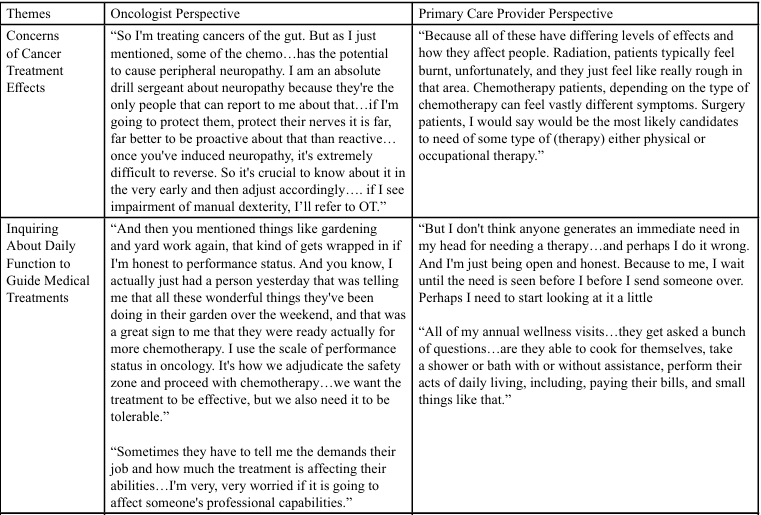

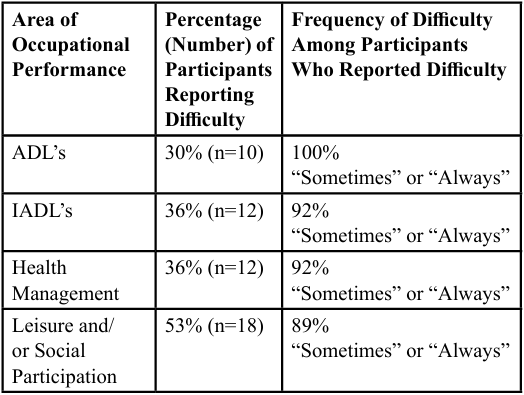

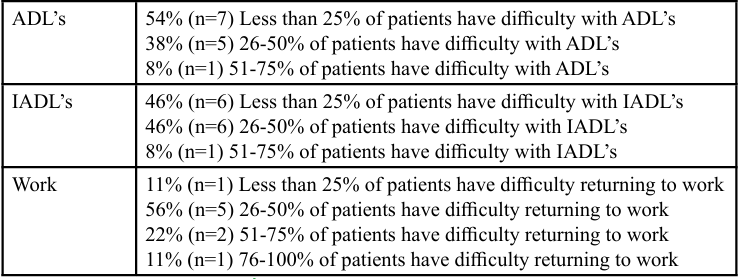

Results: Survey results from cancer survivors revealed that participants had difficulty performing activities of daily living (30%); independent living skills (36%); leisure pursuits (53%); health management (35%); and work. Fifty percent of survivors were able work part-time during their treatment but 30% did not return to work after oncological treatments. Thirty-six percent indicated their physician did not inquire if they were having difficulties with their daily occupations and 85% were never referred to occupational therapy (OT). Survey results from the physicians revealed they believed their patients had difficulty with activities of daily living (46%); instrumental activities of daily (54%); and work (92%), yet only 31% specified that they always inquire about how cancer treatments are impacting their patient’s daily routines. Four themes emerged from the survivors: (1) Challenges related to occupational participation; (2) Support enhances resilience and occupational balance; (3) Psychosocial issues influence the survivors' well being and occupational balance; and (4) Healthcare communication concerns. Four themes emerged from the physicians: (1) Concerns regarding effects of cancer treatments; (2) Need to inquire about daily function to guide medical treatments; (3) Importance of communication and rapport; and (4) Providers have limited education on how OT can benefit patients’ participation.

Conclusion: These findings reinforce the limited evidence on these topics and provide a deeper understanding of how occupational performance is affected from the perspectives of both cancer survivors and physicians.

Keywords: Occupational Therapy; Cancer; Survivors & Physicians Perspectives; Impact on Occupational Performance; Impact on Daily Life.

Introduction

One in every three people will be diagnosed with a form of cancer over the course of their lives [1]. The term cancer survivor is used to describe anyone diagnosed with cancer, regardless of where they are in their journey [1]. Cancer and the secondary effects from various oncological interventions often significantly impact the survivors’ daily life. For example, individuals enduring cancer treatments frequently experience fear, elevated levels of stress, fatigue, and a plethora of other side effects [1] which commonly lead to changes/ loss in one’s daily occupations and their roles in the home, workplace, and community [1-5]. For the purposes of this article, meaningful occupations, also known as daily occupations, include anything that a person needs or wants to accomplish in their daily life and may include things such as one’s activities of daily living (ADLs), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), rest, sleep, work, leisure, and social participation [6]. Occupational therapy interventions have been identified as being advantageous in enhancing one’s ability to remain engaged in meaningful activities and improving overall quality of life for individuals with cancer [2,5,7,8]. Although the evidence suggests the value of occupational therapy for cancer survivors, lack of awareness regarding occupational therapy’s role in being able to enhance occupational participation and quality of life for cancer survivors has led to a lack of physician referrals for occupational therapy intervention and has been identified as a main barrier to the utilization of this advantageous service [9-12].

Occurrence of Cancer in the United States

Approximately 16.9 million cancer survivors live in the United States [1]. This population is predicted to increase dramatically in the upcoming decade due to the larger and growing population of older adults, as well as an increased rate of survival due to early detection and/or improved cancer treatments [1]. Unfortunately, cancer survivors often experience a variety of side effects related to their diagnosis and/or oncological treatments. These include, but are not limited to, fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, pain, peripheral neuropathy, sexual dysfunction, issues with balance and/or mobility, gastrointestinal problems, difficulties with swallowing, difficulty with communication, and psychological concerns such as depression, anxiety and/or fear of recurrence [1,13]. Additionally, the lives of cancer survivors often revolve around numerous medical appointments, adherence to long term treatment, and extensive follow-up care to ensure they are monitored for recurrence and/or metastases [1,13]. Because this is a very stressful time, Alfano et al., [13] found that many cancer survivors have an overabundance of concerns and needs related to themselves, their family, as well as a variety of social, economic, and psychological issues. Worldwide, the definition of cancer patient and cancer survivor is debated as whether or not all people who have a diagnosis of cancer should be referred to as cancer survivors, or if this term should only be used for those in the remission phase of their diagnosis [14]. For the purposes of this study, cancer patients/survivors will be defined as individuals who have a current or previous diagnosis of cancer within the past 5 years.

Impact of Cancer Treatments on Occupational Performance

Due to the abundance of medical appointments and interventions, as well as the variety of physical, psychological, and emotional consequences of cancer, survivors commonly experience limitations in their occupational performance including basic activities of daily living (BADLs), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLS), work, and leisure activities [1,3,4, 5,7,8,15-20]. For instance, the side effects of cancer often result in activity disruption, role disengagement, and limitations in activity participation such as housework, fulfilling the role as a parent, ability to return to work, or socialize with friends [2,3,5,21]. Additionally, Player et al. [4] demonstrated how the effects of chemotherapy (e.g., memory loss and difficulty concentrating) can impact one’s performance in daily activities, specifically trouble with reading, social communication, home organization, money management, and returning to work.

Benefit of Occupational Therapy for Cancer Patients

Occupational therapy is the therapeutic use of everyday life occupations for the purpose of enhancing or enabling participation [6]. Occupational therapists are skilled at assessing the dynamic interrelationships between client factors (e.g., values and body functions), performance skills (motor, process, and social interaction skills), performance patterns (e.g., habits, routines, roles), contexts (environmental and personal factors), and occupations (e.g., ADLs, IADLs, rest and sleep, work, leisure, social participation) [6]. Occupational therapists are trained to create interventions to enhance one’s ability to do the things that they want or need to do when injuries, illnesses, and disabilities impede one’s ability to engage in meaningful activities [6]. In terms of treating patients with cancer, Polo et al. [22] asserted that occupational therapists offer value to cancer survivors by promoting engagement in one’s meaningful life roles, as well as one’s social and overall community participation. Occupational therapists also facilitate meaningful lifestyles and optimize health and well-being via various intervention strategies (e.g., addressing performance issues, use of adaptive and compensatory strategies, etc.). For example, Fleischer et al. [21] demonstrated how occupational therapy interventions with a focus on adaptation and modification strategies can increase activity participation. Likewise, Player et al. [4] demonstrated that a variety of compensatory strategies can be advantageous in circumventing the cognitive deficits associated with chemotherapy and its impact on occupational performance. Similarly, Mayer and Engle [23] reported that occupational therapy can significantly enhance the quality of life for the survivor and reduce burden on caregivers. Moreover, engagement in occupations has been found to help cancer survivors maintain a sense of control and stability, experience feelings of self-worth, and enhance self-development [21]. Thus, occupational therapy interventions have not only enhanced the survivor’s ability to maintain engagement in his or her occupations, but it also improved the patients’ overall perceived quality of life [2,24].

One occupation which appears to be greatly impacted by cancer and oncological intervention revolves around being able to fulfill the worker role. In fact, Loh et al. [19] revealed that the multiple symptoms challenge and/or impede the survivor’s ability to return to work or work at the same capacity as they did prior to their diagnosis. Returning to work not only provides the individual with a sense of purpose and normalcy, but it has also been associated with an improved quality of life [19]. Occupational therapy intervention may be critical to the survivor’s ability to return to work since modifications may be necessary to enhance work performance and/or enable one’s ability to return to work. Thus, referral to community based occupational therapy could be advantageous in not only helping the individual perform their basic self-care (ADLs) and independent living skills (IADLs), but it might be extremely advantageous in helping the cancer survivor return to work/resume their role as a worker.

OT is a Beneficial Member of the Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation Team

Comprehensive cancer rehabilitation using a multidisciplinary team is an essential component of survivorship care [22] especially since many of the adverse consequences are amenable to rehabilitation interventions [7]. In a comprehensive rehabilitation model, the multidisciplinary team evaluates the entirety of issues that a cancer survivor faces and coordinates treatment rather than treating each symptom or impairment separately [13]. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation can optimize function, improve quality of life, minimize impairments, restrictions, and activity limitations, facilitate functional independence, and minimize, psychological concerns [23,25]. Since cancer and oncological interventions commonly impact the survivors’ ability to partake in their daily routines and occupations, occupational therapy should be an essential member of the multidisciplinary rehabilitation team. As demonstrated by Petruseviciene et al., [27], community based occupational therapy has the potential to positively influence survivors’ health-related quality of life and engagement in meaningful activities. However, despite the mounting evidence regarding the benefits of occupational therapy services for cancer survivors, many national cancer survivorship programs do not routinely offer occupational therapy services [13,22]. Furthermore, Dalzell et al., [27] discovered that even with the increasing cancer survival rate, there is still no official model in place addressing the complex and comprehensive rehabilitation needs of patients with cancer.

Barriers to OT Being Part of the Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation Team

Even though occupational therapy interventions for patients with cancer have been found to be effective and beneficial, there seems to be an abundance of reasons as to why oncological patients are not receiving occupational therapy interventions. Barriers to receiving OT services included things such as lack of accessibility, failure to recognize and document impairments, failure to evaluate patient-reported impairments, as well as reluctance to refer patients to community-based services [28]. For example, Dominick et al., [29] reported that even when a cancer survivor received a referral for occupational therapy services, there were still barricades which affected their ability to comply with the suggested treatments.

Additionally, Piggott et al., [30] revealed that oncologists, oncology residents, and oncology nurses indicated that patient and family issues interfered with receiving occupational therapy interventions. Another barrier to the inclusion of occupational therapy services as part of the rehabilitation process for cancer survivors appears to be related to lack of referrals from physicians. For instance, Mattes et al. [11] highlighted that education regarding when and why a patient may need occupational therapy services while undergoing oncological treatments is often left out of the curriculum, which has resulted in medical students and physicians having little guidance in being able to determine if occupational therapy services are warranted. Thus, Mattes et al. [11] recommended developing frameworks to assist oncologists in determining if a referral is needed. Additionally, as asserted by Alfano et al. [13] and Sleight et al. [24], since referral to rehabilitation professionals is currently not part of standard care for patients with cancer, the development and implementation of oncological care models would not only assist in the receipt of referrals to occupational therapy but would help facilitate the consistent use of a multidisciplinary team approach to optimize function, health, and quality of life for the cancer survivors. Additionally, some studies have claimed that physicians have often assumed that cancer patients are too weak to handle rehabilitation during their oncological treatments; thus, they have forgone additional referrals [31,32]. Whereas Wang et al. [28] found primary care providers were more likely to utilize physical and occupational therapy services if patients were undergoing surgery as the primary cancer treatment, and less likely if radiotherapy or chemotherapy were used.

Even though newer models of service delivery advise that interventions such as occupational therapy are an essential part of the comprehensive oncological rehabilitative process [12,24] a referral from a physician is required in most states to perform occupational therapy evaluation and treatment and to receive reimbursement for those interventions. Lack of awareness regarding occupational therapy’s role in being able to enhance occupational participation and quality of life for individuals with cancer has been identified as one of the main barriers to the referral and utilization of OT services [9,10,12].

Thus, the purpose of this study is to gain a better understanding of: (1) the impact of cancer on an individuals’ ability to engage in their daily occupations (ADLs, IADLs, Work, Leisure, and Social Participation) and (2) the primary care provider’s knowledge and understanding of the impact of cancer interventions on the survivor’s ability to engage in their daily occupations as well as the provider’s decision to refer/withhold referral to occupational therapy.

Methods

Research Design

This study used a sequential explanatory mixed methods design [33,34] to gain an understanding of the patients, oncologists, and primary care providers’ perspectives regarding the impact of cancer treatments on occupational performance and to better understand why patients may or may not have received OT services. More specifically, the researchers implemented a sequential explanatory mixed methods design using a survey and focus groups; it consisted of two phases of data collection beginning with the collection of quantitative data, which was followed by the collection of qualitative data. This research design was intentionally chosen to explain and expand on the prior quantitative results and to provide a more comprehensive understanding of this topic [33,34]. This study was approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection

Quantitative data was gathered from two different researcher developed online surveys. The surveys were created on Research Electronic Data Capture (RedCap), a secure online software developed for research purposes. One of the surveys was used to gather information from cancer survivors regarding the impact of cancer and oncological treatment on their occupational performance (e.g., ADLs, IADLs, Work, Leisure, and Social Participation). The survivor online survey consisted of three demographic related questions, eleven closed ended questions, and nine open-ended questions related to perceptions of occupational performance and participation (Appendix A). The other survey was used to gather information from oncologists and primary care providers who treat individuals with cancer. The online survey for oncologists and primary care providers was used to gather information regarding their referral patterns to occupational therapy services as well as their perceptions regarding the impact of cancer and cancer treatments on their patients’ ability to perform their occupations (e.g., ADLs, IADLs, Work, Leisure, and Social Participation). This survey contained eleven closed ended questions and nine open-ended questions (Appendix B). Both researcher-developed online surveys were based on literature/current evidence and modified according to expert opinion. To gain a deeper understanding regarding this subject matter, qualitative data was gathered from focus groups and individual interviews with cancer survivors and oncologists/primary care physicians.

Participants

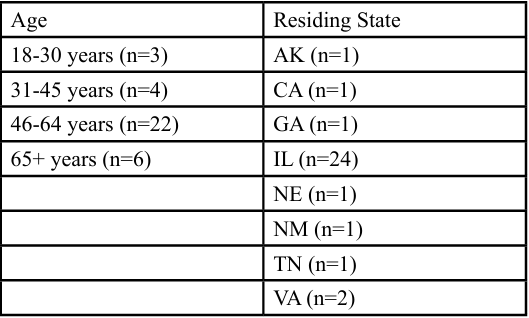

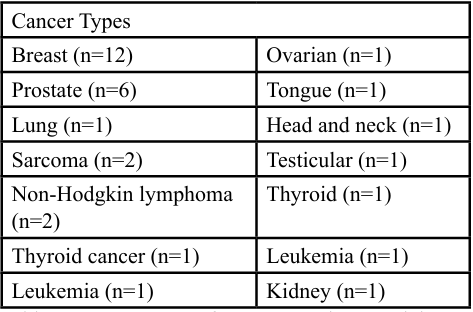

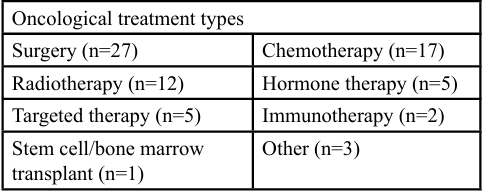

Inclusion criteria for the cancer survivor participants consisted of having a current or previously confirmed diagnosis of any cancer type within the last five years, being at least 18 years of age, and English speaking. Thirty-five cancer survivors completed the researcher developed Red Cap survey. Participants' ages ranged from 18 years to above 65 years of age and resided in 7 different states in the United States. For more detailed demographic information regarding cancer survivor participants, please see Table 1. Participants represented 15 different types of cancer (Table 2) and received a variety of oncological treatments (Table 3).

There was a wide variety of different types of cancer (n=14) and types of oncological treatments (n=10) represented by the cancer survivor participants (see Table 2 and 3 below).

A total of 10 cancer survivors participated in a focus group (n=4, n=3) or individual interview (n=3).

Inclusion criteria for the oncologists and primary care physicians consisted of practicing within the United States, currently treating or have treated a patient with a cancer diagnosis within the last five years, and English speaking. Thirteen oncologists/primary care providers completed the online Red Cap survey. These participants were from 3 different states [CO (n=2), IL (n=10), UT(n=1)]. Two physicians participated in an individual interview, one was with an oncologist and the other was with a primary care provider.

Procedure

Survey participants were recruited via posts on public social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, Twitter), professional forums (e.g., AOTA, ILOTA), emails to personal and professional acquaintances of the researchers, and via snowball sampling. The online survey included an invitation to participate in the focus group/interview at the end of the survey. Since none of the survey participants expressed interest in participating in a focus group, recruitment efforts for the focus groups were expanded by placing posts regarding the focus group on social media sites and professional forums, and via placing flyers in the community. Interested focus group participants contacted the researchers for scheduling purposes. The researchers made all efforts to try to coordinate the participants’ schedules with potential times and dates for focus groups. If the individuals wanted to participate but were not available to attend any of the focus group times, individual interviews were offered. The researchers held two focus groups (n=4, n=3) and three individual interviews with the cancer survivors and two individual interviews with the oncologist/primary care provider. The focus groups were conducted in a semi-structured format. The questions for the survivor focus group and the primary care provider/oncologist focus groups were based on literature and modified according to expert opinion (Appendix C and D). The focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, and all identifiable information was removed. The survivor focus groups lasted approximately 60-120 minutes, whereas the interviews with the survivors and physician/oncologist were approximately 30-45 minutes. All interviews/focus groups were conducted by either one or two researchers.

This study was approved by a University’s Institutional Review Board. This study was also supported by a research grant provided by the University which enabled the researchers to provide the cancer survivors with a $25 amazon gift card as a thank you for their time and participation in the focus group or individual interview.

Data Analysis

The quantitative data from the survey responses were analyzed with descriptive statistics. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the qualitative data from the focus group and responses to open-ended questions in the survey [33]. To enhance the rigor of the study, the researchers individually immersed themselves in the qualitative data by “repeated reading” as a way to gain familiarity and to begin to find patterns [33]. Next, the researchers individually generated initial codes from the data. Data analysis meetings with all researchers were used to identify patterns in the data, to reduce and group codes and identify themes. Revisions to codes and themes were made until all researchers came to consensus. The anonymity of participants was maintained throughout the data analysis process. True to a mixed methods design, both sets of data were compared during the data analysis and interpretation process. To enhance trustworthiness, peer debriefing and expert review were also used throughout the data collection and analysis process.

Results

Quantitative Data from the Survey: Cancer Survivors

Participants revealed the following symptoms impacted their ability to engage in daily routines: fatigue (n=29, 83%); pain (n=19, 55%), medical appointments & procedures (n=18, 52%); brain fog/inability to focus (n=16, 46%); and other (n=7, 20%). Approximately 30% of the participants (n=10) indicated that they had difficulty performing activities of daily living (e.g., feeding, hygiene, grooming, bathing, dressing, toileting, etc.). Whereas 36% of the participants (n=12) revealed having difficulty with instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., cooking, cleaning, grocery shopping, commuting, etc.). Similarly, 36% of the survivor participants also expressed difficulty performing health management activities (activities related to developing, managing, and maintaining health and wellness routines). In terms of leisure and/or social participation, 53% of participants indicated difficulty with this component of their life. Please see Table 4 for more details. Difficulties with leisure and/or social participation were identified in the following areas: leisure exploration (n=6, 33.3%); leisure participation (n=11, 61.1%), community participation (n=9, 50.0%), family participation (n=7, 38.9%), friendships (n=9, 50.0%), intimate partner relationships (n=12, 66.7%), peer group participation (n=7, 38.9%). In terms of fulfilling the worker role, 82% of the participants worked prior to their cancer diagnosis, however only 50% of the participants (n=17) worked during their cancer treatments. 90% of participants worked part-time during their treatment and 30% (n=10) of the participants did not return to work after the completion of their oncological treatments. Regarding support groups, 56% (n=19) reported they did not participate in a support group nor were they given information on community resources. Despite all these challenges, 64% of the participants indicated that their healthcare provider did not inquire about difficulties with daily life activities due to cancer related treatments, and 85% of the participants (n=29) were never referred to OT.

Table 4: Percentage and Frequency of Difficulty Reported with Occupational Performance Among Cancer Survivors

Quantitative Data from the Survey: Oncologists and Primary Care Providers

Approximately 31% (n=4) of the oncology and primary care physicians (PCP) participants indicated that they “always” inquire about how cancer treatments are impacting their patients’ daily routines; whereas 7.7% (n=1) responded “never”, 15.4% (n=2) responded “seldom”, and 46.2% reported that they sometimes (n=6) inquire about how cancer treatments are impacting their patients’ daily routines. Interestingly, the type of oncological intervention (surgery, chemotherapy, radiation) appeared to influence the rate of referral to occupational therapy services. Physicians reported that patients with surgical interventions (n=10, 77%), chemotherapy (n=6, 46%), and radiation interventions (n=5, 38%) “sometimes” received a referral to occupational therapy. Please see Table 5 for more details. Regarding the ability to fulfill the worker role, 92% of the PCP/oncologist participants reported that their patients had difficulty working during their oncological treatment. Similarly, 77% of the oncologist and PCP participants indicated that their patients exhibited difficulty engaging in leisure interests and social participation.

Thirty-one percent of the physician participants reported they “seldom” (n=4) and 69% (n=9) stated that they only “sometimes” refer their patients to occupational therapy services. Yet they did refer to other allied health professionals such as physical therapy (n=11, 85%), social work (n=10, 77%), and speech language pathology (n=5, 38%). Eighty-five percent (n=11) of the physician participants did not identify any reason which interfered with a referral to occupational therapy, however; 15% proclaimed that a lack of knowledge regarding occupational therapy and questioning if occupational therapy services would be covered by insurance interfered with the referral process.

Table 5: Oncologists and Primary Care Physicians Reporting of the Percentage and Frequency of their Patients Experiencing Difficulty with Occupational Performance

Qualitative Data:

Cancer Survivors Four themes emerged from the patient qualitative data: (1) Challenges related to occupational participation; (2) Support enhances resilience and occupational balance; (3) Psychosocial issues influence the survivors' well-being and occupational balance; and (4) Healthcare communication concerns.

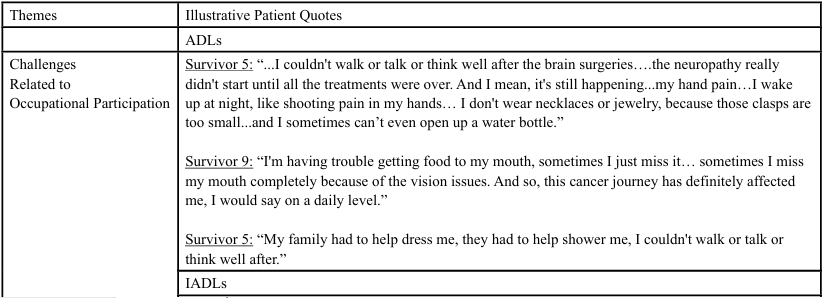

Challenges Related to Occupational Participation

Cancer survivors who participated in this research study identified many areas of occupational participation that were impacted by their cancer treatments. More specifically, the participants in this study expressed difficulty and concern regarding their ability to perform their ADLs, IADLs, rest/sleep, work, leisure, social participation, and health management. Many of these participants proclaimed that their challenges related to their occupational participation stemmed from the side effects of their cancer and/or cancer related treatments (e.g., chemotherapy). For example, many participants reported that their fatigue, cognitive changes, pain, identity changes, body image, lymphedema, and memory challenges led to disruptions in their roles, routines, and ability to engage in their daily occupations. Refer to Table 4 for specific examples.

Support Enhances Resilience and Occupational Balance

Cancer survivor participants identified many supports in their daily life that positively impacted their resilience and ability to continue to participate in meaningful activities during their cancer treatments. Participants reported that family support, partner support, community organizations, cancer survivor community and support groups, and their relationship with their health care professionals allowed them to maintain their quality of life during this time. Refer to Table 4 for specific examples.

Psychosocial Issues Influence the Survivors' Well-being and Occupational Balance

Survivor participants identified extensive impact on psychosocial well-being throughout their cancer treatment process. They reported that managing their mental health through participation in meaningful roles and routines, socialization, helping to support others, taking an attitude of gratitude, embracing challenges, and their use of humor significantly helped them in this area of their well-being. Conversely, cancer survivor participants identified concerns such as uncertainty and loss of control in their current and future life, which were challenging for them to accept. They also reported that at times they felt angry about their diagnosis and how it impacted their relationships, while also having a desire to maintain their independence, difficulty accepting changes in their identity, and concern for recurrences of cancer. Some coping strategies they reported included finding ways to adapt how they engaged in daily activities, prioritizing what they did every day, choosing to remain hopeful for the future, and persistence in participation in meaningful occupations and roles. Refer to Table 4 for specific examples.

Healthcare Communication Concerns

Even though some of the participants expressed that some of their health care providers were very helpful, encouraging, and beneficial, participants conveyed that some of their health care providers did not make them feel heard and did not address their concerns. As a result, the participants shared that in these situations they did not feel comfortable talking about concerns, which could have influenced their recovery and quality of life. Additionally, patients reported that there were times that certain aspects of their diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment process were not clearly discussed and/ or communicated with them by their health care providers. Thus, participants claimed that these types of circumstances resulted in confusion, safety concerns, and challenges with treatment adherence. Furthermore, the majority of participants revealed that there was little to no communication regarding other services, such as occupational therapy, which may have been beneficial for their recovery and quality of life, and perhaps could have enhanced their occupational participation. Refer to Table 6 for specific examples.

Qualitative data: Health Care Providers

Four themes emerged from the qualitative data are: (1) Concerns regarding effects of cancer treatments; (2) Need to inquire about daily function to guide medical treatments; (3) Importance of communication and rapport; and (4) Providers have limited education on how OT can benefit patients’ participation.

Concerns Regarding Effects of Cancer Treatments

Oncologists and PCPs identified a myriad of concerns regarding secondary symptoms and the impact of cancer treatments. Some areas of concern they mentioned included things such as neuropathy, decreased dexterity, falls, and difficulties with ADLs, IADLs, work, and medication management. They reported that having good rapport was important in gathering reliable information regarding effects of cancer treatments. Providers also reported communicating with their patients regarding their favorite leisure activities, hobbies, and the ability to engage in everyday tasks; however, they also mentioned that they do not have a protocol for evaluating performance in all areas nor do they routinely ask about all areas of occupation. Refer to Table 7 for specific examples.

Need to Inquire About Daily Function to Guide Medical Treatments

Providers reported that they inquire about their patients’ ability to participate in daily activities during visits to guide the intensity of treatments based on performance measures completed by the patients. The physicians also used these as a way to know if they need to make any additional referrals to other health care professionals. Furthermore, the providers discussed that patient responses seem to include saying that everything is fine or that they are having extensive challenges. Additionally, they indicated that leisure and social participation are not routinely asked about throughout the treatment process and are very limited to the intake forms when first admitted. The providers mentioned that one way they can gauge the accuracy of what the patients are saying is if a family member comes to appointments with them and talks about how they are able to function in daily activities. Refer to Table 5 for specific examples.

Importance of Communication and Rapport

Providers reported that making sure that their patients have access and education on resources is important to address during their visits with patients. Developing a strong and comfortable line of communication was mentioned as very important by the providers. Some ways they do this are through learning what their patients enjoy doing, what is important to them, keeping conversations fun, and caring for patients as they would for family. Providers expressed that patients report feeling capable to do many activities with little difficulty while others report that they have extensive challenges and safety concerns. The providers reported that many patients are unaware of ways to address this and that there are trained professionals that can help support them in these areas of concern. Although these providers do their best to ensure a healthy relationship with their patients, there are some systemic barriers which can impact this. For example, the patients’ plan of care is often determined by a team of doctors, especially as they progress to the later stages of survivor hood; even though having more perspectives can be beneficial, it can also be overwhelming for patients. Additionally, the larger the healthcare team becomes, there is greater risk in valuable information not being relayed to all members of the team. Furthermore, access to other professionals such as occupational therapy can be halted because of patients not wanting to go to another appointment, not having insurance or funding, lack of transportation, and lack of comprehensive evaluations (e.g., identification of occupational performance difficulties) leading to unaddressed patient needs. Refer to Table 5 for specific examples.

Providers Have Limited Education on Benefits of OT Services for Cancer Patients

Providers were able to identify several reasons related to limited education of how their patients could benefit from other healthcare disciplines throughout the survivorship continuum. Additionally, hesitancy about certain topics seemed to bolden providers’ lack of awareness about the value of other health care professionals, specifically the benefits of OT. Providers reported they received formal education of OT, physical therapy (PT), psychology, and speech language pathology (SLP) in medical school, but it was a very brief overview of each profession. They explained that further learning about OT, as well as other health care professionals, came informally from exposure to family members in these fields and/ or exposures to professional encounters in various clinical settings. Moreover, they indicated that when they learned more about OT outside of their formal education, that it helped improve their listening and observation skills related to their patients' ADL and IADL performance. The physician participants in this study also reported they tended to refer to OT and PT frequently, despite not having any formal education to inform their referral process.

Providers reported that there is special emphasis on patient safety at their facilities and there is an automatic referral process for PT if a patient is deemed to be at risk of falling, yet there is no such referral process for OT referrals. Furthermore, providers showed extensive knowledge on the benefits of PT for patient safety in comparison to their knowledge about the benefits of OT. As a result of these interviews, providers expressed that they believe further learning about how OT can help with daily participation challenges for their patients would lead to earlier referral to OT services. Providers reported that some barriers to OT referral included difficulty with navigating electronic medical record systems at certain hospitals in contrast to easier referral processes at other locations. Providers did show appreciation regarding the benefits OT for lymphedema management in their patients as well as practical skills in adapting various activities with cancer patients. Refer to Table 5 for specific examples.

Discussion

This study examined cancer survivors’ and physicians’ perspectives regarding (1) the impact of cancer on an individuals’ ability to engage in their daily occupations (ADLs, IADLs, Work, Leisure, and Social Participation) and (2) the physicians’ knowledge and understanding of the impact of cancer interventions on the survivor’s ability to engage in their daily occupations as well as their decision to refer/ withhold referral to occupational therapy. The results of this study support the limited existing evidence and provided additional insight into a relatively unexplored topic. Not only did the quantitative and qualitative results of this study support each other and the limited existing literature, but the qualitative findings from this study also provided a deeper understanding of this topic, added to the existing evidence related to this subject matter, and enhanced the trustworthiness of the findings.

Similar to previous findings, the survivor participants in this study revealed that cancer survivors experienced difficulties with occupational participation and engagement in ADLs, IADLs, work, leisure, social participation, and health management activities [3,5,7,8,15-20]. Similar to Alfano et al. [13], the survivors in this study indicated that they experienced many side effects during and after their oncological intervention which played havoc to their daily occupations and routines. The participants in this study also reported that their lives were consumed with managing many medical appointments and they expressed a plethora of other challenges related to their family and other relationships, work demands, as well as their mental health. Despite all of these challenges, analogous to Wang et al. [28], the majority of participants in this study did not receive referrals for occupational therapy, nor did their physician inquire about the impact of cancer on their occupational performance, even though there is evidence to suggest that OT interventions can be an extremely beneficial service for cancer survivors [21,22]. Additionally, similar to Wang et al. [28] the quantitative findings from the physician participants reinforced that physician do not consistently inquire about the impact of cancer on their patients’ occupational performance, nor do they routinely refer their patients to occupational therapy. However, the cancer survivors in this study did discuss how the support they received from health care providers, fellow cancer survivors, family, friends, and colleagues deeply supported their ability to engage in the activities they found meaningful as well as their mental well-being, despite the significant changes that took place after their cancer diagnosis. Moreover, the qualitative data from the physicians did reveal that they inquire about their patients’ daily function as a way to gauge the intensity of oncological interventions.

Similar to Wang et al. [28] the physician participants in this study disclosed that they received limited education and possess limited knowledge regarding the role and benefits of occupational therapy for cancer survivors. Unfortunately, for a cancer survivor to receive OT services, they need to receive an order for evaluation and treatment from their oncologist, PCP, or one of their physicians. Due to the lack of awareness, knowledge, and education physicians receive in medical school, supportive services are likely not being implemented because the need is not noticed by physicians [9,10,12]. The results of this study support the above notion as the physician participants stated that they did not have knowledge of what OT is, nor did they feel confident in making referrals for occupational therapy services. Thus, the results of this study seem to suggest that there is a pressing need to educate medical students and practicing healthcare providers regarding the benefits of these types of services.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although the findings of this study included a smaller sample size and a small geographical location pool, rich data was provided through the survey, focus groups, and interviews of patients and providers. The results of this study may not be generalizable due to its small participant pool, particularly lacking support from medical professionals to participate in the study, as well it’s small and unequal geographical representation. Future directions should include greater and broader sample sizes, formatting the survey and focus group questions in a more accessible way for those not familiar with occupational therapy, a focus on psychosocial interventions occupational therapists can use in oncology, educational interventions for physicians, especially oncologists and PCP’s, regarding the scope of occupational therapy practice, providing patients and families with resources to know when to talk with their doctor about concerns they are having in everyday occupations, activities, and routines, and providing education to other health care professionals (e.g., PTs, SLPs, etc.) regarding the role and value of OT with cancer survivors.

Implications and Conclusion

The findings from this study reinforce the limited evidence on these topics and provide a deeper understanding of how occupational performance is affected from perspectives of both cancer survivors and physicians. This study addressed a gap in the literature regarding how cancer treatments impact everyday life of cancer survivors, as well as how oncologists and PCPs are addressing the everyday needs of cancer survivors during, post treatment, and throughout the cancer survivorship continuum. Furthermore, the findings of this study appear to reinforce the limited current evidence which reveals that OT services are not well understood by the medical professional gatekeepers of OT referrals. Even though occupational therapy can play a significant role in enhancing one’s quality of life and ability to engage in their meaningful occupations, if and oncologists and PCP’s lack knowledge of how occupational therapists can help cancer survivors, referrals to occupational therapy services will be limited. Thus, this study supports previous researchers who have advocated for better guidelines and models which can help guide and address the complex and comprehensive rehabilitation needs of patients with cancer.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

American Cancer Society (2019). Cancer Facts & Figures 2022. Atlanta: American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer. org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2022/2022-cancer facts-and-figures.pdfView

Lyons, K. D., Erickson, K. S., & Hegel, M. T. (2012). Problem solving strategies of women undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(1), 33–40.View

Pergolotti, M., Williams, G. R., Campbell, C., Munoz, L. A., & Muss, H. B. (2016). Occupational therapy for adults with cancer: Why it matters. The Oncologist, 21(3), 314-319. https:// doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0335 View

Player, L., Mackenzie, L., Willis, K., & Loh, S. Y. (2014). Women’s experiences of cognitive changes or ‘chemobrain’ following treatment for breast cancer: A role for occupational therapy? Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 61(4), 230–240.View

Sleight, A. G., & Duker, L. I. (2016). Toward a broader role for occupational therapy in supportive oncology care. The American journal of occupational therapy, 70(4), 7004360030p1 7004360030p8.View

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl. 2),7412410010.View

Hunter, E. G., Gibson, R. W., Arbesman, M., & D’Amico, M.(2017). Centennial topics—systematic review of occupational therapy and adult cancer rehabilitation: Part 2. Impact of multidisciplinary rehabilitation and psychosocial, sexuality, and return-to-work interventions. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71, 7102100040. View

Longpre', S. M., Polo, K. M., & Baxter, M. F. (2020). A personal perspective on daily occupations to counteract cancer related fatigue: A case study. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 8(1), 1-10.View

Buckland, N. & Mackkenzie, L. (2017). Exploring the role of occupational therapy in caring for cancer survivors in Australia: A cross-sectional study. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 64, 358368.View

Hwang, E. J., Lokietz, N. C., Lozano, R. L., & Parke, M. A. (2015). Functional deficits and quality of life among cancer survivors: Implications for occupational therapy in cancer survivorship care. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69(6), 7403205140p1-7403205140p9.View

Mattes, M. D., Patel, K. R., Burt, L. M., & Hirsch, A. E. (2016). A nationwide medical student assessment of oncology education. Journal of Cancer Education. 31(4), 679–686. View

Silver, J. K., Baima, J., & Mayer, R. S. (2013). Impairment driven cancer rehabilitation: An essential component of quality care and survivorship. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 63(5), 295-317.View

Alfano, C. M., Cheville, A. L., & Mustian, K. (2016). Developing high-quality cancer rehabilitation programs: A timely need. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Annual Meeting, 35, 241–249.View

Surbone, A., Annunziata, M. A., Santoro, A., Tirelli, U., & Tralongo, P. (2013). Cancer patients and survivors: Changing words or changing culture? Annals of Oncology, 24(10), 2468 2471.View

Baxter, M. F., Newman, R., Longpre', S. M., & Polo, K. M. (2019). AOTA official documents in the AJOT online supplement. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(6). https://doi:10.5014/ajot.2019.736offdoc View

Hegel, M. T., Lyons, K. D., Hull, J. G., Kaufman, P., Urquhart, L., Li, Z., & Ahles, T. A. (2010). Feasibility study of a randomized controlled trial of a telephone-delivered problem-solving-occupational therapy intervention to reduce participation restrictions in rural breast cancer survivors undergoing chemotherapy. Psycho-Oncology, 20(10), 1092 1101.View

Huri, M., Huri, E., Kayihan, H., & Altuntas, O. (2015). Effects of occupational therapy on quality of life of patients with metastatic prostate cancer. A randomized controlled study. Saudi Medical Journal, 36(8), 954961. https://doi.org/10.15537/ smj.2015.8.11461View

Lai, L., Player, H., Hite, S., Satyananda, V., Stacey, J., Sun, V., Hayter, J. (2021). Feasibility of REMOTE occupational therapy services via telemedicine in a breast cancer recovery program. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, February 2021, Vol. 75, 7502205030. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2021.042119View

Loh, S. Y., Sapihis, M., Danaee, M., & Chua, Y. P. (2020). The role of occupational- participation, meaningful-activity and quality-of-life of colorectal cancer survivors: findings from path-modelling. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–10. Advance online publication.View

Peoples, H., Brandt, A., Wæhrens, E. E., la Cour, K. (2017) Managing occupations in everyday life for people with advanced cancer living at home. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 24:1, 57-64, DOI: 10.1080/11038128.2016.1225815View

Fleischer, A., & Howell, D. (2017). The experience of breast cancer survivors’ participation in important activities during and after treatments. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 80(8), 470–478. View

Polo, K. M., & Smith, C. (2017). Centennial topics—taking our seat at the table: Community cancer survivorship. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71,7102100010.View

Mayer, R. S., & Engle, J. (2022). Rehabilitation of Individuals with Cancer. Annals of rehabilitation medicine, 46(2), 60–70. View

Sleight, A. G. (2017). Centennial topics—occupational engagement in low-income Latina breast cancer survivors. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71, 7102100020. View

Khan, F., Amatya, B., Drummond, K., & Galea, M. (2014). Effectiveness of integrated multidisciplinary rehabilitation in primary brain cancer survivors in an Australian community cohort: a controlled clinical trial. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 46(8), 754–760.View

Petruseviciene, D., Surmaitiene, D., Baltaduoniene, D., & Lendraitiene, E. (2018). Effect of community-based occupational therapy on health-related quality of life and engagement in meaningful activities of women with breast cancer. Occupational Therapy International, 1–13. View

Dalzell, M. A., Smirnow, N., Sateren, W., Sintharaphone, A., Ibrahim, M., Mastroianni, L., Vales Zambrano, L. D., & O'Brien, S. (2017). Rehabilitation and exercise oncology program: translating research into a model of care. Current Oncology (Toronto, Ont.), 24(3), e191–e198.View

Wang, J. R., Nurgalieva, Z., Fu, S., Tam, S., Zhao, H., Giordano, S. H., Hutcheson, K. A., & Lewis, C. M. (2019). Utilization of rehabilitation services in patients with head and neck cancer in the United States: A SEER-Medicare analysis. Head and Neck, 41(9), 3299–3308.View

Dominick, S. A., Natarajan, L., Pierce, J. P., Madanat, H., & Madlensky, L. (2014). Patient compliance with a health care provider referral for an occupational therapy lymphedema consult. Supportive care in cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 22(7), 1781–1787.View

Piggott, K. L., Patel, A., Wong, A., Martin, L., Patel, A., Patel, M., Liu, Y., Dhesy-Thind, S., & You, J. J. (2019). Breaking silence: a survey of barriers to goals of care discussions from the perspective of oncology practitioners. BMC cancer, 19(1), 130.View

Boris, C., Eda, T., Burra, N., et., (2018). Avoiding sedentary behaviors requires more cortical resources than avoiding physical activity: An EEG study. Neuropsychologia, 119:68-80. View

Kwon, D. H., Tisnado, D. M., Keating, N. L., Klabunde, C. N., Adams, J. L., Rastegar, A., Hornbrook, M. C., & Kahn, K. L. (2015). Physician-reported barriers to referring cancer patients to specialists: prevalence, factors, and association with career satisfaction. Cancer, 121(1), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1002/ cncr.29019View

Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Sage.View

Winston, K. A. & Powers Dirette, D. (2022). Clarifying mixed methodology in occupational therapy research. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 10(2), 1–3.View