Journal of Rehabilitation Practices and Research Volume 6 (2025), Article ID: JRPR-161

https://doi.org/10.33790/jrpr1100162Research Article

Mike Studer

1Adjunct Professor, Touro University Las Vegas, Las Vegas, 4505 S. Maryland Pkwy, NV, 89154, United States.

2Physical Therapy Instructor (PTI), The University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 4505 S. Maryland Pkwy, NV, 89154, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Mike Studer, PT, DPT, MHS, NCS, CEEAA, CWT, CSST, CSRP, CBFP, FAPTA, Adjunct Professor, Touro University Las Vegas, Las Vegas, 4505 S. Maryland Pkwy, NV, 89154, United States.

Received date: 27th January, 2025

Accepted date: 25th March, 2025

Published date: 28th March, 2025

Citation: Studer, M., (2025). Practical Applications in Lifespan and Healthspan: Debunking the Myths, Fads, Trends and Gimmicks - and Adding Choice!. J Rehab Pract Res, 6(1):162.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Without regard to a specific age that one would like to survive to, most all of us would want to live healthy lives fully up to the point of death. The news feeds, podcasts, magazines and infomercials are filled with advice about how to live longer, yet far less content, product, and media is focused on healthspan. We have more options to choose from now than we have everhad on diets, supplements, sleep aides, and exercise – both in movements and machines. Having options is not the primary problem. Knowledge is not the primary problem. While it is frequently blamed, having the time to implement healthy strategies is also not the primary problem. Why is it then that healthspan is not keeping pace with lifespan?

Perhaps the solutions that have been implemented from these scientific advancements - are the problem. We now have more education, fewer work hours/more time for self-help, more gimmicks and life hacks than we have ever held. What is going to move people to choose better, to adopt evidence-based strategies to extend healthspan? The approaches that have been used to coerce, guilt, shame, or convince people have been ineffective. These approaches have included more myths about aging than ever, more approaches endorsed by figures of authority, and even more legislative solutions. We have tried these and are barely living longer than we were decades ago.

The solution may be in stepping back and providing choice. Choice provides autonomy, enhances self-efficacy and elevates belief. Choice empowers these three powerful tools to make any solution more effective.

Introduction

As an overview, this article will guide both laypersons and healthcare providers to achieve the following outcomes. By the end of this article, you should be able to:

- Define and contrast the terms healthspan and lifespan

- Identify the power of choice, in healthspan and lifespan decisions

- Debunk the myths of aging, specifically what can be controlled and what should be “blamed on” the physiologic processes of aging

- Identify the power of physical activities that optimize safety and wellness

- Identify nutritional strategies designed for longevity and function

- Identify the science of social support and purposefulness on healthspan

- Identify wellness opportunities through a balance of rest and challenge

- Identify controlled, extreme conditions in the form of temperature, exertion, pressure and novelty in order to remain capable, adaptable, and healthy (detailed further in article 2 of 2)

Improving your familiarity and confidence in the translations of science across the five pillars (physical activity, nutrition, social connection, sleep/rest and novel experiences) may nudge you to make healthier choices for yourself. In addition, knowing these practical and evidence-based applications will empower you to not only choose for yourself, but also empower you to guide both patients or family members accordingly, by providing them with fewer prescriptions and more choices.

This first of a two-article series is intended to be an introductory level for each of the five pillars listed above, with a primary focus on choice, the science of aging, and physical activity. The second article will feature greater depth on the complementary knowledge of applied behavioral economics as specifically applied to both healthspan and lifespan changes. Readers will note that a deeper dive summary with supportive references is provided to conclude each section, providing the reader with greater depth in the physiologic connections than this article can cover.

Part One: Squaring the Curve Toward Maximizing Healthspan

Healthspan is a relatively new term, a spinoff of lifespan if you will. As you may already know or may expect from the compound word formed, healthspan refers to the length of time that you can remain healthy, which includes “functioning independently”. The World Health Organization (WHO) uses the term Healthy Life Expectancy (HALE) for healthspan. Details and statistics on healthspan and lifespan are included in Part Three of this article entitled, Aging – A deeper dive.

There has been an explosion in popularity of recent publications and podcasts about healthspan. Many of these discussions interchange the phrases, “squaring the curve” and “compressed morbidity” for healthspan.

The late author and rheumatologist Dr. John H. Bland died in 2007, at 90 years old. Bland was the author of Live long, die fast: Playing the aging game to win, and in the game of healthspan, “win” he did. Bland may not have been the original source of the phrase “live long and die fast”, yet his 1996 book of the same title was among the first to use these words together, referring to healthspan that approximates lifespan.

Part Two: The Power of Choice

Nearly every variable that we can manipulate to improve our own health will benefit from belief. Actively choosing an option, and thereby increasing belief, will provide returns in the forms of intensity, engagement, attention and consistency. Lifespan and healthspan can be elevated when we have chosen a diet, a sleep routine, a marathon-training plan, a cold-immersion experience, and more. Because of these differences (consistency, attention, belief, intensity, engagement), employing choice gives you the opportunity to – and greater likelihood of – optimizing your wellness and healthspan.

Choice is often the difference between realizing your potential (achieving health outcomes) and stopping early. Making a choice requires that you formulate an opinion, have a belief, communicate self-efficacy, and in most cases endorse your selection. Most authorities on change, wellness and health will tell you that making a difference in your body requires consistency, time, dosage (often exchanged for intensity), measurement, and challenge. When we have the autonomy to choose for ourselves, we tolerate more (intensity) for a longer period (consistency). As stated above, choice gives any option that you choose a better chance to succeed.

When two or more options are equally as healthy for you (forms of exercise, diet strategies, or medications), the option that you choose will be more successful because of your belief in that option. Your decision to consume or start something that feels healthy: “I choose to do this, this is my plan” will be received quite differently by the body and mind than something that is not of your will but you must do by coercion, guilt, or fear of negative reinforcement. In time, a series of choices made consistently can become a habit and even more permanent still - an identity.

Consider the word pairs in the following list. Study them carefully with the context of health and wellness in mind. By the end, you may see a recurrent theme in the word/phrase pairs.

Loneliness – Alone time

Food insecurity – Time-restricted feeding

Forced labor – Workout

Sleep deprivation – All-nighter

Blizzard – Cold immersion

Heat advisory – Sauna

Results

The difference in each pair of conditions listed is choice. The first word/condition in the pairing is most often experienced without choice. The second is (most) often voluntary. The same conditions (lack of food, sleep, intense work, company) can be received or perceived as positive or negative – all based on choice. The longterm health and wellness results and how to make these choices for our healthspan benefit. Healthcare providers should read on in this article, tolearn additional tools that will help you work with others to actualize these opportunities.

Ultimately, what resonates with you will be more effective for you. There is extensive evidence for the benefit of belief and autonomy, inherent in health-based choices. Some of the most often cited articles in this space include [1-4].

The power of choice: Summarized

When you make the choice, you are more likely to gamify and challenge yourself to continue to excel; more likely to participate consistently (staying power or “grit”); participate with intensity and receive a better dosage; participate with belief and benefit from confirmation bias as well as the placebo effect. This should lead you to seeing results, reinforcing your choice and ultimately pivoting your self-efficacy and identity.

Part Three: Debunking the myths of aging

At a cellular level, we all age at different rates. Additionally, our rate of aging varies throughout our lifetime, based on exposures, stressors, and lifestyle choices (activity, sleep, nutrition). Research informs us that aging is more than skin deep and is influenced as noted above. Among the hundreds of studies that have proven this, Yegorov and colleagues spoke about stress in their [5] article by writing,

“People exposed to chronic stress age rapidly. The telomeres in their cells of all types shorten faster. Inflammation is another important feature of stress that, along with aging, accounts for the phenomenon of inflammaging. In addition to aging itself, inflammaging can contribute to the development of several pathologies, including atherosclerosis, diabetes, hypertension, and others. Oxidative stress is one of the main mechanisms related to stress, leading to tissue damage, inflammation, oxidation and telomere shortening.”

A developing finding that connects higher intensity exercise to lifespan and healthspan is the very intriguing topic of Klotho. Klotho is a protein that is now well-recognized as an aging-suppressor that is influential in an array of signaling-molecule pathways and a variety of processes. The momentum on Klotho experimentation and discussion has been picking up steadily over the past few years, and rightly so. Klotho has positive implications on such direct and indirect aging processes as: anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic (improving natural cellular death and recycling processes), antioxidant, and anti-tumor actions, all of which relate to lifespan.

While much of what we blame on aging cannot be stopped, it can be mitigated. The four main consensus variables that are controllable and impact or rates of aging include but are not limited to: inactivity, stress, sleep deprivation and the consumption of highly (ultra) processed diets.

A short list of processes that appear to be controllable (rate of degradation) include:

- Reduced Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) – A main fertilizer for neuroplasticity (making new connections, learning) which becomes less plentiful as we age. The expression of BDNF can be influenced by nutrition, sleep, and physical activity [6].

- Cortical Atrophy – Our brains most typically shrink in gray matter volume as we age, leaving extra room in the skull, which is not necessarily a good thing. The pace of cortical atrophy can be influenced by sleep, novel experiences, cognitive stimulation, environmental exposure and physical activity [7].

- Cellular Senescence – The cycle of cellular damage leading to cell death slows down and sometimes goes awry, leaving damaged cells behind to decay, which is never a good thing. The health and pace of cellular senescence can be influenced by environmental exposures, nutrition, physical activity and sleep [8].

- Sarcopenia – The loss of skeletal muscle, affecting endurance, strength and power. Not surprisingly, sarcopenia is highly influenced by nutrition (protein intake, physical activity (particularly resistance exercise) and novel stimulation with periodized exertion [8-10].

- Reduced Tissue Hydration, Collagen and (Bone) Density – Bone deposition slows, tendons become less-well hydrated and more disorganized (collagen fiber matrix), and the intervertebral discs lose hydration. Tissue hydration as well as bone and tendon health can be influenced by nutrition, physical activity, and sleep. Expressing growth hormone (GH) and giving ourselves the best opportunity to benefit from GH, is key here [11].

- DNA content fragility: Changes (substitutions, mutations, deletions) to DNA (Deoxyribonucleic Acid, our genes) as well as our telomeres (protective end caps on DNA)

- Energy dysregulation: Inefficiencies and reductions in mitochondria (energy production centers in the cells). Most often, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) are causal.

- Stem cell exhaustion: The reduction of stem (progenitor) cell production and development to mature into specialized cells (e.g., skin, liver, cardiac, neural, muscle)

- Reduced cell-cell communication: Diminished capability of different cells to communicate their health and energy needs to one other

- DNA structural changes: Epigenetic alterations and proteostasis leading to protein misfolding and methylation, often not due to aging, but rather: psychological stress, diet, obesity, physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol, environmental pollutants, and shift work

- A sense of wellness through the release of natural antidepressants

- The release of neuromodulator dopamine (DA): success, reward, pursuit

- More intensity and consistent engagement, as the activities are enjoyable*

- An enhanced relationship with movement through “wins” and gamified experiences

- 60 seconds, three times per day of moving hard

- People that engaged in 1-2 minutes of vigorous physical activity had a nearly 40% lower risk of dying over the course of the over seven-year study

- Lower your risk for cancer, heart disease, diabetes and more by “doing what you do” (movement in your life) with some intensity. You can accumulate 3-4 minutes per day of VILPA in segments as small as 30 seconds at a time. Research shows that you can earn 4 times (or more) the amount spent in movement back in your lifespan.

- The release of growth factors (BDNF, IGF, cytokines and myokines) leading to improved neurogenesis, neuroplasticity and angiogenesis [6, 15].

- The production of lactate, serving as energy for neurons (neurotrophic), and protection to the blood-brain barrier [15-17].

- The release of exerkines, Klotho, anti-inflammatory cytokines, and Extracellular Superoxide Dismutase - improving the immune system and neutralizing free radicals [18, 19].

- Increase in mitochondrial biogenesis + antioxidant enzyme activity [20, 21].

- Release of transmitters (DA, 5HT), boosting cognition and mental health [22, 23].

- Dual tasking (challenging cognitive and physical operations in a separate manner simultaneously) is among the most effective and efficient approaches to boost cognition and improve skill retention [24-28].

- Every minute of high intensity physical activity may earn a person 4 to 7 minutes of lifespan saved, in return. [29-30]

- Being inactive (subjected to complete bedrest) for 30 days can imitate and actually outpace the systemic effects of 30 years of normal aging (30 days of bedrest being worse for your lifespan than 30 years of aging) [31].

- Protein is something that we continue to understand better and cannot afford to reduce across any diet. The human body will largely adjust the need for protein intake to accommodate availability, within reason. Current evidence supports .8g of protein per kg of body weight. This is less than .5 grams of protein per pound of body weight.

- Strength training (physical activity against resistance) stimulates muscle synthesis (reinforcement and growth) and makes muscles more sensitive to protein intake – for a 24–48-hour window after exertion (known as the anabolic window). Current evidence suggests 20g of protein per meal minimum to take full advantage of this windowof elevated protein consumption, as high as 1.8-2.0 g/kg body weight per day depending on the caloric deficit, may be advantageous in preventing lean mass losses [32].

- Calories in and calories out equations and approaches toward weight loss are inaccurate, impersonal and too reductive. Timing of food intake is nearly as significant as content, within reason [33]. Persistent grazing may lead to energy storage, while excessive time between meals can do the same.

- A varied diet with goals for consuming foods representing more than 30 different plants per week can be healthy for your gut microbiome [34, 35].

- Efforts to lose weight often result in losing muscle mass – an unhealthy tradeoff, Dehydration and loss of skeletal muscle are two of the fastest means to effect change on the scale. These could be helpful only in the very short term, to achieve a goal weight. The results are destructive in both medium and long term. It is very difficult to regain muscle as we age [36].

- Liquid calories (meal replacement shakes, smoothies) have some drawbacks as they can create blood sugar spikes (absorption rates faster) and reduce our sense of fullness (leading to over nourishment) [37].

- Dietary approaches should be both gender- and person-specific. While it may be tempting to prescribe a Mediterranean diet for all, the benefits are largely person-specific and relate to the benefit of this person’s microbiome, ultimately and primarily through the production of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) [38].

- Timing of food intake is nearly as significant as content, within reason [33]. Persistent grazing may lead to energy storage, while excessive time between meals can do the same.

- Not all fat is equal. Brown fat can be healthy and helpful for insulation, protection, energy storage and metabolism regulation. White fat would have fewer of these beneficial characteristics and can build our risk for inflammatory disorders as well as many cancers [39].

- Physical activity can help to regulate appetite in efforts toward healthy weight loss via lactate signaling and the lactate-toghrelin pathway [40, 41].

- Ultra processed foods (UPFs) are among the most dangerous changes in our diet over the past 5 decades. As Whelan and colleagues [42] wrote, “There is increasing evidence of an association between diets rich in UPFs and gut disease, including inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer and irritable bowel syndrome…UPFs have themselves been shown to affect gut health…emulsifiers, sweeteners, colors, and microparticles and nanoparticles have effects on a range of outcomes, including the gut microbiome, intestinal permeability and intestinal inflammation.”

- We have more microbiota (living organisms) in our gut than we have cells in our body, approximately 39 trillion of the 76 trillion total cells in our body (combined). We benefit from a diverse and healthy microbiome in order to maximize our food absorption, minimize inflammation, signal cravings, and regulate blood sugar. High fiber and (separately) fermented foods including kombucha, miso, some yogurts (live cultures), tempeh, kimchi, more aged cheeses and sauerkraut have been found to be beneficial to the microbiome. [34, 35, [44-46]]

- Your gut microbiome produces 90-95% of your serotonin [47].

- Response to specific foods, added sugars, and many dietary approaches will remain variable based on genetics (SNPs), microbiota, activity levels and past exposure.

- Fasting for 20 hours, then consuming all calories in one sitting, or continuous grazing can each leave us with a blunted metabolism and tendency to store energy locally. Chrononutrition, time restricted feeding and intermittent fasting approaches all agree on one singular approach - providing cells and microbiota an opportunity to rest and respirate between feedings [48, 49]

- We are influenced-by and influence those closest to us, for positive and negative attributes. This includes our healthcare team, co-workers, family and friends [52, 53].

- A more well-developed Theory of Mind (ToM), yielding an accurate appreciation for thoughts and perspectives of people in my family, circle, community, and beyond. This in turn can help our mental health and ultimately our socialization, vocation and quality of life [54, 55].

- Memory health – Brain regions optimized through diverse experiences and educational offerings [54, 56].

- Many of the healthiest regions in the world (Blue Zones) are now thought to be most successful in lifespan not because of climate or diet, but due to the social inclusion and purpose-filled lives with roles for older adults [57-59].

- Improved mental health through actions – Helping/serving others by choice [60].

- Reducing the health losses associated with unintentional solitude (loneliness) [50, 51, 56, 61].

- Capturing intentional solitude (choosing to be alone) when desired/needed [62, 63].

- Healthy social connections include pet ownership, which has been shown to reduce cortisol, blood pressure, persistent pain and cardiometabolic health.

- Humans benefit from a balance of the parasympathetic and sympathetic drives of our autonomic nervous system, largely represented by heart rate variability (HRV). There are many variables involved in this balance; some are controllable, and some are not. Both rest and play can improve this balance, toward a more homeostatic level of function.

- Neurotransmitters, neuromodulators, respiration, and wholebrain connectedness improves through engaging in play and innovation

- Recent science sleep hygiene (preparing our environment and experiences for optimal sleep) can impact the four main predictors of sleep health: quality, quantity, regularity and timing (QQRT) [65, 66].

- Benefits of sleep are now proven in cognitive health, disease prevention through digestive and metabolic health nutrition, benefiting and recovering from exercise, as well as learning (consolidation) [67-70].

- Rest is person specific. It does not need to lead to orinclude sleep. Rest can include experiences of awe [71], mindfulness (improving awareness of self or surroundings), meditation (concentrated time in silence, focus, and reflection with reframing), and even play (reduced perceptions of pressure, time, performance). These can lead to health benefits across but not limited to the cardiac, metabolic, neurologic, musculoskeletal and endocrine systems [3, 18, 72]

- The power of play is a field of science crossing multiple disciplines: movement, rehabilitation, psychology, development, and more. As James Clear writes in his 2018 bestseller, Atomic Habits, "When you're on the field, play as if nothing else matters. When you're off the field, remember that the game doesn't matter at all.". Play can help cognition, heart rate variability, efforts toward homeostasis, mental health and more [54, 73].

- Muscle repair (recovery) [77, 79, 80]

- Reaction speed [81]

- Blood sugar regularity

- Immune system health [82]

- The science on sleep hygiene summarized as QQRT. Quantity, quality, regularity and timing. Readers are directed to Dr. Matt Walker’s 2017 book, “Why We Sleep” and in his guest appearance on the Huberman Lab podcast in April 2024 for more details. The direct relationships to metabolic disease, degenerative disease, chronic pain, are well established.

- Deep sleep provides an opportunity to clean the brain of toxins. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulates intensely to remove buildup (β-amyloid and tau) as well non-waste products such as dietary and environmental toxins, glucose, lipids, amino acids, and neurotransmitters [83-85].

- Our sleep cycles serve as an optimal time for neuroplasticity. This time is used to both prune unused information and store what we experienced that day (known as consolidation) [84].

- There is an emerging science on the parameters of sleep hygiene. Rather than attempting to detail each of the variables, suffice to say that in a range of 90-120 minutes before sleep one could limit these stimuli:

- Artificial light – Circadian rhythm, wakefulness

- Strenuous exercise – Cortisol, body temperature

- Volumes of fluid consumption – Bladder

- Nutrition that would constitute a meal – Blood sugar

- Stress/conflict (observed on TV or directly experienced) – Cortisol, wakefulness

- Alcohol consumption – artificial depressant

- Caffeine – none within 6 hours of attempting to sleep

- Consistently choose physical activities to optimize safety and wellness

- Choose healthier options and portions to gather needed energy

- Surround myself with diverse people to expand my social health

- Optimize wellness through a balance of rest and activities with people, in places that feel healthy

- Expose myself to conditions in the form of temperature, exertion, pressure and novel experiences in an effort to remain capable, adaptable, and healthy (more in article 2)

Pink, D. H. (2011). Drive. Canongate Books. Prestongate, Scotland.

Dunn, C., Haubenreiser, M., Johnson, M., Nordby, K., Aggarwal, S., Myer, S., & Thomas, C. (2018). Mindfulness Approaches and Weight Loss, Weight Maintenance, and Weight Regain. Current obesity reports, 7(1), 37–49.View

Lynn, S., Satyal, M. K., Smith, A. J., Tasnim, N., Gyamfi, D., English, D. F., Suzuki, W. A., & Basso, J. C. (2022). Dispositional mindfulness and its relationship to exercise motivation and experience. Frontiers in sports and active living, 4, 934657.View

Parra, D. C., Wetherell, J. L., Van Zandt, A., Brownson, R. C., Abhishek, J., & Lenze, E. J. (2019). A qualitative study of older adults' perspectives on initiating exercise and mindfulness practice. BMC geriatrics, 19(1), 354.View

Yegorov, Y. E., Poznyak, A. V., Nikiforov, N. G., Sobenin, I. A., Orekhov, A. N. (2020). The Link between Chronic Stress and Accelerated Aging. Biomedicines. 7; 8(7):198.View

Rody, T., De Amorim, J. A., & De Felice, F. G. (2022). The emerging neuroprotective roles of exerkines in Alzheimer's disease. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 14, 965190.View

Volkers, K. M., Scherder, E. J. (2011). Impoverished environment, cognition, aging and dementia. Rev Neurosci. 22(3):259-66.View

Izquierdo, M., Merchant, R. A., Morley, J. E., Anker, S. D., Aprahamian, I., Arai, H., Aubertin-Leheudre, M., Bernabei, R., Cadore, E. L., Cesari, M., Chen, L. K., de Souto Barreto, P., Duque, G., Ferrucci, L., Fielding, R. A., García-Hermoso, A., Gutiérrez-Robledo, L. M., Harridge, S. D. R., Kirk, B., Kritchevsky, S., … Fiatarone Singh, M. (2021). International Exercise Recommendations in Older Adults (ICFSR): Expert Consensus Guidelines. The journal of nutrition, health & aging, 25(7), 824–853.View

Prud'homme, G. J., Kurt, M., & Wang, Q. (2022). Pathobiology of the Klotho Antiaging Protein and Therapeutic Considerations. Frontiers in aging, 3, 931331.View

Rolland, Y., Dray, C., Vellas, B., & Barreto, P. S. (2023). Current and investigational medications for the treatment of sarcopenia. Metabolism: clinical and experimental, 149, 155597.View

Kusy, K., & Zieliński, J. (2015). Sprinters versus longdistance runners: how to grow old healthy. Exercise and sport sciences reviews, 43(1), 57–64.View

GBD (2021). Diseases and Injuries Collaborators (2024). Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990- 2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet (London, England), 403(10440), 2133– 2161.

Garmany, A., & Terzic, A. (2024). Global Healthspan-Lifespan Gaps Among 183 World Health Organization Member States. JAMA network open, 7(12), e2450241.View

Studer, M. (2024). The Brain That Chooses Itself: Personalized Strategies to Extend Your Healthspan.

Leppäluoto, J., Huttunen, P., Hirvonen, J., Väänänen, A., Tuominen, M., & Vuori, J. (1986). Endocrine effects of repeated sauna bathing. Acta physiologica Scandinavica, 128(3), 467– 470.View

Stephan, J. S., & Sleiman, S. F. (2021). Exercise Factors Released by the Liver, Muscle, and Bones Have Promising Therapeutic Potential for Stroke. Frontiers in neurology, 12, 600365.View

El Hayek, L., Khalifeh, M., Zibara, V., Abi Assaad, R., Emmanuel, N., Karnib, N., El-Ghandour, R., Nasrallah, P., Bilen, M., Ibrahim, P., Younes, J., Abou Haidar, E., Barmo, N., Jabre, V., Stephan, J. S., & Sleiman, S. F. (2019). Lactate Mediates the Effects of Exercise on Learning and Memory through SIRT1-Dependent Activation of Hippocampal Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 39(13), 2369– 2382.View

Yan, Z., & Spaulding, H. R. (2020). Extracellular superoxide dismutase, a molecular transducer of health benefits of exercise. Redox biology, 32, 101508.View

Corrêa, H. L., Raab, A. T. O., Araújo, T. M., Deus, L. A., Reis, A. L., Honorato, F. S., Rodrigues-Silva, P. L., Neves, R. V. P., Brunetta, H. S., Mori, M. A. D. S., Franco, O. L., & Rosa, T. D. S. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrating Klotho as an emerging exerkine. Scientific reports, 12(1), 17587.View

Gu, Y., Seong, D. H., Liu, W., Wang, Z., Jeong, Y. W., Kim, J. C., Kang, D. R., Lee, R. J. E., Koh, J. H., & Kim, S. H. (2024). Exercise improves muscle mitochondrial dysfunctionassociated lipid profile under circadian rhythm disturbance. The Korean journal of physiology &pharmacology : official journal of the Korean Physiological Society and the Korean Society of Pharmacology, 28(6), 515–526.View

Sinha, J. K., Jorwal, K., Singh, K. K., Han, S. S., Bhaskar, R., & Ghosh, S. (2024). The Potential of Mitochondrial Therapeutics in the Treatment of Oxidative Stress and inflammation in Aging. Molecular neurobiology, 10.1007/s12035-024-04474-0. Advance online publication.View

Negm, A. M., Kennedy, C. C., Thabane, L., Veroniki, A. A., Adachi, J. D., Richardson, J., Cameron, I. D., Giangregorio, A., Petropoulou, M., Alsaad, S. M., Alzahrani, J., Maaz, M., Ahmed, M. M., Kim, E., Tehfe, H., Dima, R., Sabanayagam, K., Hewston, P., Abu Alrob, H., & Papaioannou, A. (2019). Management of Frailty: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 20(10), 1190–1198.View

Fiatarone Singh, M. A., Gates, N., Saigal, N., Wilson, G. C., Meiklejohn, J., Brodaty, H., Wen, W., Singh, N., Baune, B. T., Suo, C., Baker, M. K., Foroughi, N., Wang, Y., Sachdev, P. S., & Valenzuela, M. (2014). The Study of Mental and Resistance Training (SMART) study—resistance training and/or cognitive training in mild cognitive impairment: a randomized, doubleblind, double-sham controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 15(12), 873–880.View

Castaño, L. A. A., Castillo de Lima, V., Barbieri, J. F., de Lucena, E. G. P., Gáspari, A. F., Arai, H., Teixeira, C. V. L., Coelho-Júnior, H. J., & Uchida, M. C. (2022). Resistance Training Combined with Cognitive Training Increases Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Improves Cognitive Function in Healthy Older Adults. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 870561.View

Aminirakan, D., Losekamm, B., & Wollesen, B. (2024). Effects of combined cognitive and resistance training on physical and cognitive performance and psychosocial well-being of older adults ≥65: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ open, 14(4), e082192.View

Castillo de Lima, V., Castaño, L. A. A., Sampaio, R. A. C., Sampaio, P. Y. S., Teixeira, C. V. L., & Uchida, M. C. (2023). Effect of agility ladder training with a cognitive task (dual task) on physical and cognitive functions: a randomized study. Frontiers in public health, 11, 1159343.View

Studer-Luethi, B., Meier, B. Is Training with the N-Back Task More Effective Than with Other Tasks? N-Back vs. Dichotic Listening vs. Simple Listening. J CognEnhanc 5, 434–448 (2021).View

Studer, M. (2018). Making balance automatic again: Using dual tasking as an intervention in balance rehabilitation for older adults. SM Gerontology and Geriatric Research, 2(1), 1-11.

Moore, S. C., Patel, A. V., Matthews, C. E., Berrington de Gonzalez, A., Park, Y., Katki, H. A., Linet, M. S., Weiderpass, E., Visvanathan, K., Helzlsouer, K. J., Thun, M., Gapstur, S. M., Hartge, P., & Lee, I. M. (2012). Leisure time physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity and mortality: a large pooled cohort analysis. PLoS medicine, 9(11), e1001335.View

Lee, D. H., Rezende, L. F. M., Joh, H. K., Keum, N., Ferrari, G., Rey-Lopez, J. P., Rimm, E. B., Tabung, F. K., & Giovannucci, E. L. (2022). Long-Term Leisure-Time Physical Activity Intensity and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Prospective Cohort of US Adults. Circulation, 146(7), 523–534.View

Mitchell, J. H., Levine, B. D., McGuire, D. K. (2019). The Dallas Bed Rest and Training Study: Revisited After 50 Years. Circulation. Oct 15;140(16):1293-1295.View

Phillips, S. M., & Van Loon, L. J. (2011). Dietary protein for athletes: from requirements to optimum adaptation. Journal of sports sciences, 29 Suppl 1, S29–S38.View

Wilkinson, M. J., Manoogian, E. N. C., Zadourian, A., Lo, H., Fakhouri, S., Shoghi, A., Wang, X., Fleischer, J. G., Navlakha, S., Panda, S., & Taub, P. R. (2020). Ten-Hour Time-Restricted Eating Reduces Weight, Blood Pressure, and Atherogenic Lipids in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome. Cell metabolism, 31(1), 92–104.e5.View

McDonald D, Hyde E, Debelius JW, Morton JT, Gonzalez A, Ackermann G, Aksenov AA, Behsaz B, Brennan C, Chen Y, DeRightGoldasich L, Dorrestein PC, Dunn RR, Fahimipour AK, Gaffney J, Gilbert JA, Gogul G, Green JL, Hugenholtz P, Humphrey G, Huttenhower C, Jackson MA, Janssen S, Jeste DV, Jiang L, Kelley ST, Knights D, Kosciolek T, Ladau J, Leach J, Marotz C, Meleshko D, Melnik AV, Metcalf JL, Mohimani H, Montassier E, Navas-Molina J, Nguyen TT, Peddada S, Pevzner P, Pollard KS, Rahnavard G, Robbins-Pianka A, Sangwan N, Shorenstein J, Smarr L, Song SJ, Spector T, Swafford AD, Thackray VG, Thompson LR, et al. (2018). American gut: an open platform for citizen science microbiome research. mSystems 3:2020.View

Oliver, A,, Chase, A. B., Weihe, C., Orchanian, S. B., Riedel, S. F., Hendrickson, C. L., Lay, M., Sewall, J. M., Martiny, J. B. H., Whiteson, K. (2021). High-Fiber, Whole-Food Dietary Intervention Alters the Human Gut Microbiome but Not Fecal Short-Chain Fatty Acids. mSystems. Mar 16; 6(2):e00115-21.View

Bikou, A., Dermiki-Gkana, F., Penteris, M., Constantinides, T. K., &Kontogiorgis, C. (2024). A systematic review of the effect of semaglutide on lean mass: insights from clinical trials. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy, 25(5), 611–619.View

Heden, T. D., Liu, Y., Sims, L., Kearney, M. L., Whaley-Connell, A. T., Chockalingam, A., Dellsperger, K. C., Fairchild, T. J., & Kanaley, J. A. (2013). Liquid meal composition, postprandial satiety hormones, and perceived appetite and satiety in obese women during acute caloric restriction. European journal of endocrinology, 168(4), 593–600.View

Merra, G., Noce, A., Marrone, G., Cintoni, M., Tarsitano, M. G., Capacci, A., & De Lorenzo, A. (2020). Influence of Mediterranean Diet on Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients, 13(1), 7.View

Ahn, C., Zhang, T., Yang, G., Rode, T., Varshney, P., Ghayur, S. J., Chugh, O. K., Jiang, H., & Horowitz, J. F. (2024). Years of endurance exercise training remodel abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue in adults with overweight or obesity. Nature metabolism, 6(9), 1819–1836.View

Vanderheyden, L. W., McKie, G. L., Howe, G. J., Hazell, T. J. (2020). Greater lactate accumulation following an acute bout of high-intensity exercise in males suppresses acylated ghrelin and appetite postexercise. J Appl Physiol (1985). May 1;128(5):1321-1328.View

McCarthy, S. F., Tucker, J. A. L., & Hazell, T. J. (2024). Exercise-induced appetite suppression: An update on potential mechanisms. Physiological reports, 12(16), e70022.View

Whelan, K., Bancil, A. S., Lindsay, J. O., &Chassaing, B. (2024). Ultra-processed foods and food additives in gut health and disease. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 21(6), 406–427View

Marano G, Mazza M, Lisci FM, Ciliberto M, Traversi G, Kotzalidis GD, De Berardis D, Laterza L, Sani G, Gasbarrini A, Gaetani E. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: Psychoneuroimmunological Insights. Nutrients. 2023 Mar 20;15(6):1496.View

Sender, R., Fuchs, S., Milo, R. (2016). Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol. Aug 19;14(8):e1002533.View

Tlais, A. Z. A., Polo, A., Granehäll, L., Filannino, P., Vincentini, O., De Battistis, F., Di Cagno, R., &Gobbetti, M. (2024). Sugar lowering in fermented apple-pear juice orchestrates a promising metabolic answer in the gut microbiome and intestinal integrity. Current research in food science, 9, 100833.View

Merra, G., Noce, A., Marrone, G., Cintoni, M., Tarsitano, M. G., Capacci, A., & De Lorenzo, A. (2020). Influence of Mediterranean Diet on Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients, 13(1), 7.View

Terry, N., Margolis, K. G. (2017). Serotonergic Mechanisms Regulating the GI Tract: Experimental Evidence and Therapeutic Relevance. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;239:319- 342.View

Ofori-Asenso, R., Owen, A. J., & Liew, D. (2019). Skipping Breakfast and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Death: A Systematic Review of Prospective Cohort Studies in Primary Prevention Settings. Journal of cardiovascular development and disease, 6(3), 30. View

Flanagan, A., Bechtold, D. A., Pot, G. K., & Johnston, J. D. (2021). Chrono-nutrition: From molecular and neuronal mechanisms to human epidemiology and timed feeding patterns. Journal of neurochemistry, 157(1), 53–72. View

Loneliness has same risk as smoking for heart disease. (2016, June 16). Harvard Health. Retrieved January 12, 2025, View

Social connection — Current priorities of the U.S. surgeon general. (n.d.). Department of Health & Human Services | HHS. gov. Retrieved January 12, 2025,View

Rohn, J. (1996). 7 strategies for wealth & happiness: Power ideas from America's Foremost business philosopher. Harmony.

Borges, M. D., Ribeiro, T. D., Peralta, M., Gouveia, B. R., & Marques, A. (2024). Are the physical activity habits of healthcare professionals associated with their physical activity promotion and counselling?: A systematic review. Preventive medicine, 108069. Advance online publication.View

Clear, J. (2018). Atomic habits: An easy & proven way to build good habits & break bad ones. Penguin.

Sun, C., Wang, N., & Geng, H. (2024). Adopting the visual perspective of a group member is influenced by implicit group averaging. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 10.3758/ s13423-024-02531-2.View

Weinstein, N., Vuorre, M., Adams, M., & Nguyen, T. V. (2023). Balance between solitude and socializing: everyday solitude time both benefits and harms well-being. Scientific reports, 13(1), 21160.View

Buettner, D. (2010). The blue zones: Lessons for living longer from the people Who've lived the longest. National Geographic Books.

Aliberti, S. M., Donato, A., Funk, R. H. W., &Capunzo, M. (2024). A Narrative Review Exploring the Similarities between Cilento and the Already Defined "Blue Zones" in Terms of Environment, Nutrition, and Lifestyle: Can Cilento Be Considered an Undefined "Blue Zone"?. Nutrients, 16(5), 729. View

Deeg, D. J. H., van Tilburg, T., Visser, M., Braam, A., Stringa, N., & Timmermans, E. J. (2024). Identification of a "Blue Zone" in the Netherlands: A Genetic, Personal, Sociocultural, and Environmental Profile. The Gerontologist, 64(11), gnae132. View

Theurer, K. A., Stone, R. I., Suto, M. J., Timonen, V., Brown, S. G., & Mortenson, W. B. (2022). "It Makes You Feel Good to Help!": An Exploratory Study of the Experience of Peer Mentoring in Long-Term Care. Canadian journal on aging = La revue canadienne du vieillissement, 41(3), 451–459. View

Courtin, E., & Knapp, M. (2017). Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: a scoping review. Health & social care in the community, 25(3), 799–812. View

Zambrano Garza, E., Pauly, T., Choi, Y., Murphy, R. A., Linden, W., Ashe, M. C., Madden, K. M., Jakobi, J. M., Gerstorf, D., & Hoppmann, C. A. (2024). Daily solitude and wellbeing associations in older dyads: Evidence from daily life assessments. Applied psychology. Health and well-being, 16(1), 356–375. View

Birditt, K. S., Manalel, J. A., Sommers, H., Luong, G., & Fingerman, K. L. (2019). Better Off Alone: Daily Solitude Is Associated With Lower Negative Affect in More Conflictual Social Networks. The Gerontologist, 59(6), 1152–1161. View

Tao, H., Pepe, J., Brower, A., & Robinson, P. S. (2023). The CREATION Health Assessment Tool for Patients (CHAT-P): Development & Psychometric Testing. Journal of religion and health, 62(3), 2144–2162. View

Walker, M. (2017). Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. Simon & Schuster View

Huberman, A. (2024, April 24). Dr. Matt Walker: Protocols to improve your sleep. On The Huberman Lab [Podcast].

Chang, X., Sun, L., & Li, R. (2023). Application of symbolic play test in identification of autism spectrum disorder without global developmental delay and developmental language disorder. BMC psychiatry, 23(1), 138.

Windred, D. P., Burns, A. C., Lane, J. M., Saxena, R., Rutter, M. K., Cain, S. W., & Phillips, A. J. K. (2024). Sleep regularity is a stronger predictor of mortality risk than sleep duration: A prospective cohort study. Sleep, 47(1), zsad253. View

Steiger A. (2007). Neurochemical regulation of sleep. Journal of psychiatric research, 41(7), 537–552.

Shekhar, S., Hall, J. E., &Klubo-Gwiezdzinska, J. (2021). The Hypothalamic Pituitary Thyroid Axis and Sleep. Current opinion in endocrine and metabolic research, 17, 8–14. View

Sturm, V. E., Datta, S., Roy, A. R. K., Sible, I. J., Kosik, E. L., Veziris, C. R., Chow, T. E., Morris, N. A., Neuhaus, J., Kramer, J. H., Miller, B. L., Holley, S. R., & Keltner, D. (2022). Big smile, small self: Awe walks promote prosocial positive emotions in older adults. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 22(5), 1044–1058. View

Thompson, B. L., & Waltz, J. (2007). Everyday mindfulness and mindfulness meditation: Overlapping constructs or not? Personality and Individual Differences, 43(7), 1875–1885. View

Turin, T. C., Kazi, M., Rumana, N., Lasker, M. A. A., & Chowdhury, N. (2023). Conceptualising community engagement as an infinite game implemented through finite games of 'research', 'community organising' and 'knowledge mobilisation'. Health Expect. Oct; 26(5):1799-1805. View

Edmiston, E. K., Merkle, K,, & Corbett, B. A. (2015). Neural and cortisol responses during play with human and computer partners in children with autism. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. Aug;10 (8):1074-83. View

Williams, A. M., Hogg, J. A., Diekfuss, J. A., Kendall, S. B., Jenkins, C. T., Acocello, S. N., Liang, Y., Wu, D., Myer, G. D., Wilkerson, G. B. (2022). Immersive Real-Time Biofeedback Optimized With Enhanced Expectancies Improves Motor Learning: A Feasibility Study. J Sport Rehabil. Jun 20; 31(8):1023-1030. View

Wu, S., Ji, H., Won, J., Jo, E. A., Kim, Y. S., & Park, J. J. (2023). The Effects of Exergaming on Executive and Physical Functions in Older Adults With Dementia: Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of medical Internet research, 25, e39993. View

Cadegiani, F. A., Silva, P. H. L., Abrao, T. C. P., & Kater, C. E. (2021). Novel Markers of Recovery From Overtraining Syndrome: The EROS-LONGITUDINAL Study. International journal of sports physiology and performance, 16(8), 1175– 1184. View

Khan, M. A., & Al-Jahdali, H. (2023). The consequences of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance. Neurosciences (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), 28(2), 91–99.View

Rosenblum, Y., Weber, F. D., Rak, M., Zavecz, Z., Kunath, N., Breitenstein, B., Rasch, B., Zeising, M., Uhr, M., Steiger, A., & Dresler, M. (2024). Sustained polyphasic sleep restriction abolishes human growth hormone release. Sleep, 47(2), zsad321.View

Church, D. D., Gwin, J. A., Wolfe, R. R., Pasiakos, S. M., & Ferrando, A. A. (2019). Mitigation of Muscle Loss in Stressed Physiology: Military Relevance. Nutrients, 11(8), 1703.View

Vitale, K. C., Owens, R., Hopkins, S. R., & Malhotra, A. (2019). Sleep Hygiene for Optimizing Recovery in Athletes: Review and Recommendations. International journal of sports medicine, 40(8), 535–543.View

Sochal, M., Ditmer, M., Turkiewicz, S., Karuga, F. F., Białasiewicz, P., &Gabryelska, A. (2024). The effect of sleep and its restriction on selected inflammatory parameters. Scientific reports, 14(1), 17379.View

Jessen, N. A., Munk, A. S., Lundgaard, I., & Nedergaard, M. (2015). The Glymphatic System: A Beginner's Guide. Neurochem Res. Dec; 40(12): 2583-99.View

Fultz, N. E., Bonmassar, G., Setsompop, K., Stickgold, R. A., Rosen, B. R., Polimeni, J. R., & Lewis, L. D. (2019). Coupled electrophysiological, hemodynamic, and cerebrospinal fluid oscillations in human sleep. Science (New York, N.Y.), 366(6465), 628–631.View

Rowe, R. K., Schulz, P., He, P., Mannino, G. S., Opp, M. R., & Sierks, M. R. (2024). Acute sleep deprivation in mice generates protein pathology consistent with neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in neuroscience, 18, 1436966.View

Dixon, M. L., & Dweck, C. S. (2022). The amygdala and the prefrontal cortex: The co-construction of intelligent decisionmaking. Psychological review, 129(6), 1414–1441.View

Many of these processes are correlated with aging, and some are definitively caused by aging. Most importantly, many of the attributes and even losses that we have long associated with aging now have research-proven strategies to mitigate their expression.

Among the processes that do not appear to be influenced using any of these five conservative pillars, is nerve conduction velocity. Age does appear to cause a reduction in the speed of nerve conduction (transmitting a signal from one end of a nerve to the other). Functionally, this results in increased reaction time (takes longer), potentially increasing falls, reducing power (speed to recruit muscles), visual acuity, hearing, and more.

The Effect of Personal Beliefs and Life Experiences, on Aging

“I can’t do that anymore, I’m too old”

At the societal and personal level, we blame a lot of the changes we experience with age, on the natural and obligatory changes from aging. Do the natural processes of aging truly cause or merely correlate with the experience of aging? Is aging to blame for as much as we assign it? In reviewing this list of controllable processes, one might give pause and ask about the “normal” aging processes. How is choice involved? How much of what we expect to happen with aging, in fact occurs because we expect it to happen (self-imposed values/ beliefs)? How much of what we blame on aging occurs because we change our lives as we get older, which causes the changes in our body (remove stimuli for strength, mental operations, purpose)? How much of what we blame on aging happens because our society directs it to happen? Is it a societally-actualized (rather than self-fulfilling) prophecy that when we stop, meeting new people, meeting deadlines at work, running, jumping, cycling, preparing meals or managing our own finances – that we lose the fundamental skills required for these tasks?

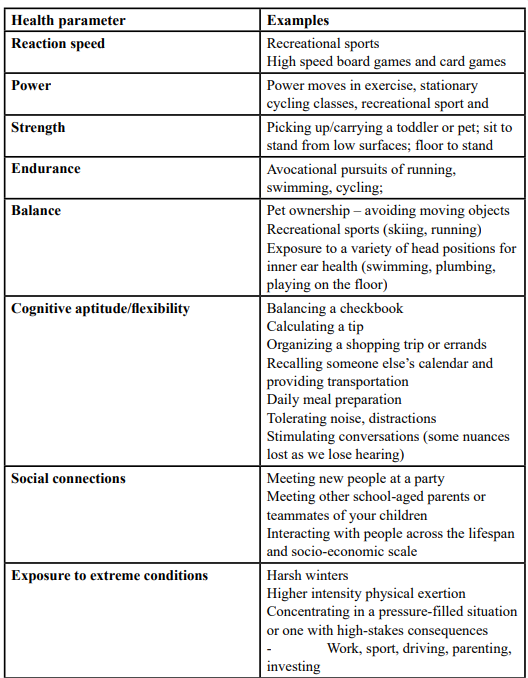

Table 1: provides insights that may be helpful for your own life. You may see activities that people commonly stop doing as they age may in fact be the precipitant or accelerate some of the losses that we blame on age. Some of these activities are stopped because the person who is aging is no longer engaged in them. This is the case for work for a lot of people. Some activities are stopped because society tells us that “people that age” don’t “do that” (bike, run, ride skateboards). Most importantly, use this table to check yourself. Check your beliefs that you impose on yourself and those you pass on to others.

Aging – A Deeper Dive

As with each section of this paper, there are many deep-dive concepts that are beyond the scope of this article. The reader is directed to the references, most notably the book, The Brain That Chooses Itself for full coverage and depth of this material. For aging, the additional concepts with evidence now and that are being researched in aging include:

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), life expectancy across all populations and genders is just over 71 years. This value had been climbing consistently since the year 2000, gaining over 6 years in length from nearly 67 to over 73 years through 2019. According to the WHO in a separate publication, health span is not keeping pace, “While healthy life expectancy (HALE) [12] has increased by 9% from 58.1 in 2000 to 63.5 in 2019, this was primarily due to declining mortality rather than reduced years lived with disability. In other words, the increase in HALE (5.3 years).” Healthspan is not keeping pace with the increase in life expectancy (6.4 years), leaving the world with more years of disability than ever.

Trends in the United States are notoriously outpacing the world, according to, lead author of a recent Mayo Clinic study, Dr. Armin Garmany as he wrote [13], “The widening healthspan-lifespan gap globally points to the need for an accelerated pivot to proactive wellness-centric care systems". This same study revealed a worldwide-peak and widening gap between lifespan and healthspan in the US. Americans are now living 12.4 years on average with disability and sickness. This (13%) increase is alarming from the average of 10.9 years in 2000.

Part Four: Physical Activity to Extend Healthspan, and Lifespan - in that order

The following four processes that serve as the basis for this section. By engaging in physical activity that we choose, we may and likely will benefit both our lifespan and healthspan through:

*Recall that the definitions of “joy” and “enjoyable” are and should always be person specific. Meaning, find or seek help to find physical fitness opportunities in activities that you love!

Physical activity, exercise, movement – words do matter. Exercise is for the purpose of fitness. It involves structure and sometimes dosage (intensity, weight/resistance, speed, length of time). Physical activity can be recreational (a walk in nature), volunteer, vocational, sporting (competitive or playful), and it can even mean exercise. Physical activity can be much more inclusive, easier to reach, and therefore adopted. The thought of exercise can seem selfish (as it might have been in times of war) or even repulsive to some people.

While the phrase, “exercise is medicine” is popular, perhaps it should be replaced with the phrase, “physical activity is medicine”. By clearly including, welcoming and celebrating all forms of physical activity as healthy, we may invite more people that do not meet the current WHO activity guidelines to identify themselves as active people. This invites people to do more, rather than leaving them shamed feeling that the standards are unreachable. It is important to extend the notion that being active with our bodies for the purposes of work, workout, and yard work - are all healthy and “count” toward these minutes. Some prefer to categorize exercise as “prescription medicine” and physical activity as “over the counter medicine” [14].

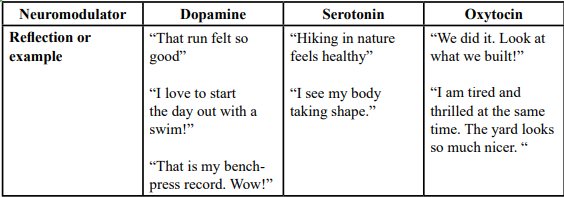

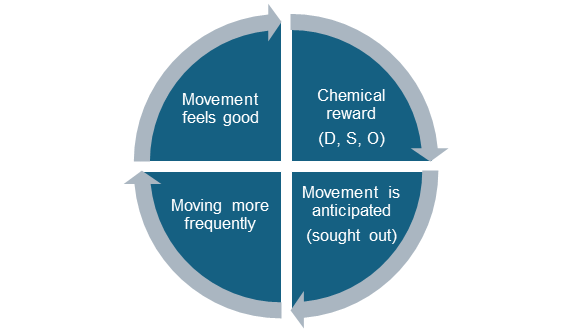

When the brain has chosen to exert the body, we can feel a sense of wellness that is largely chemically based (neuromodulators and signaling molecules). When your chosen form of physical activity provides a sense of reward, a person is more likely to seek out that sensation again in the future. With repeated pleasant experiences, we create associations with PA (event based or episodic memories) that feel successful or productive (raked leaves, scored a goal, walked the dog, helped to build a play structure). These associations become connected in the brain, initially through a chemical reward, and later through new connections in the brain, learning, neuroplasticity.These connections and the downstream chemical responses (“physical activity gives me purpose”) can create a positive or virtuous cycle through this reward system. A simplified version of this is represented in Table 2. This positive cycle includes virtuous, as participation (being physically active) which can increase the desirable sensation (endorphin, reduced sense of depression), thereby giving the mover some reason to continue, as well as reason to seek this out again. This movement to sensation to memory loop can help to reinforce our choices, forming both habits and an identity that can lead to more consistency. Consistency is an important part of exercise and all forms of PA, leading to fitness and respecting tissue hygiene. If we are rarely active, but very intense when we move… injury becomes more likely. However, when engaged in movement that is enjoyable or purposeful, we can expect to devote greater intensity, attention, and the all-important attendance (consistency). These attributes may yield greater outcomes, thereby increasing our sense of attachment and reward to the activity – a virtuous cycle as depicted in Figure 1.

D = Dopamine O = Oxytocin S = Serotonin

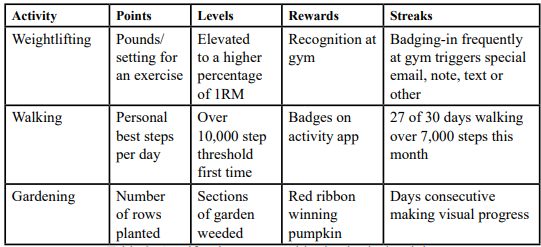

It is now commonplace to speak about, read about, or receive notifications and rewards associated with our movement. We see this in the medical sector with badges for accomplishing a home exercise program; clubs and gyms recognizing people for frequent attendance; apps rewarding for new personal best scores in speed, number of steps/day, and so forth. All of these can be considered forms of gamification. According to Kennard et al, “Gamification is a means of adding game-like elements to a traditionally non-game activity. This has been shown to be effective in providing a more engaging experience and improving adherence.”

Physical activity can be gamified. There are just too many ways to gamify PA to list them all here. A few of the most common would include tracking steps, calories, miles, personal bests, repetitions, weights, consecutive days, watts, revolutions per minute (watts or RPMs on your bike), and even rankings (compared to peers). Again, gamification can help us to deepen and reinforce our relationship with movement, while supporting physiologic gains in the form of neuroplasticity (connections in the brain), improved blood flow, and so much more.

The most widely recognized means of gamification come in the forms of points, levels, rewards, and streaks. Table 3 provides examples of each, within the context of PA.

If intense PA is more beneficial when chosen, how does the body receive intense work when it is compulsory? How does the body respond to any of these levers when there is no choice, but are a part of involuntary draft into the military, part of torture, or a part of service/incarceration? Despite all of the cited benefits of physical activity, when it is forced labor – it is uniformly unhealthy. Drydakis writes about the negative effects on mental and physical health in his 2023 article entitled, “Forced Labor and Health-Related Outcomes.”

When we choose physical activity, it does not take much to have received an effective dosage:

The second newsworthy and encouraging fact is that physical activity can “buy you time.” According to Stamatakis and colleagues from their 2022 study on Vigorous Intermittent Lifestyle Physical Activity (VILPA) that included over 25,000 subjects:

VILPA is very simply “changing gears” of your daily movement for a few very brief periods per day. If you are walking to get the mail, go fast for 30 seconds. If you are getting up from the couch, sit back down and do 5 more stand ups as fast as you can before walking away. If you need to go up a set of stairs in your office building, VILPA could include the act of grabbing a railing and take that one flight of stairs two steps at a time. If you are wheeling your chair to walk your dog…engage in VILPA by simply picking up the pace for 45 seconds.

Physical Activity - A deeper dive

There are many deep-dive concepts in physical activity that are beyond the scope of this article. Greater depth is available in the references associated, and the book, The Brain That Chooses Itself. By engaging in physical activity that we choose, we will likely benefit through:

For still greater depth, readers may consider further reading on these three principles:

A summary of what strength training does for brain health can be reduced to these points: reduces systemic inflammation, improves insulin resistance, reduces abnormal protein accumulation, and mitigates mitochondrial dysfunction. These processes in turn can effectively combatheart attacks and heart failure, metabolic diseases like diabetes, most cancers, chronic pain, and most autoimmune conditions. Insulin resistance is linked to fatty liver, diabetes, and obesity, not to mention fatigue and dysfunction in energy regulation.

Part Five: Healthy Options and Portions – The Science for lifespan and healthspan

We are coming to a consensus, that in the realm of nutrition, there may be no consensus. Among all the approaches, gimmicks, supplements, fads and hyperbole - there is more noise than health. A brief list of the approaches includes time-restricted eating, intermittent fasting, keto, vegan, paleo, and low-carbohydrate. It is tempting to be reductive and suggest that one is best for everyone. The fallacy in a one-approach model is evident when we recognize the person-specific variables including digestive enzymes, microbiota, insulin storage systems, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs/ genetics), and more. The postulates of nutrition for optimal aging include:

For readers of all backgrounds, healthcare providers, laypersons, and those in the wellness industry, here are the primary bullet points regarding healthspan, lifespan and nutrition:

It is possible that the 2020s will be redefined as the decad of the gut. We are hearing terms such as gut health, the microbiome, probiotics, “the gut is your second brain”, fecal transplant, “dementia is diabetes of the brain”, and the gut brain axis on a regular basis in mainstream media (magazines, news broadcasts and social media). There is much still to be known about the bidirectional gut to brain influences, yet it is now estimated that the relationship is more unidirectional than bidirectional, with many authors, including Marano and colleagues [43] reporting that approximately 90% of the communication between the two organs comes from the gut, to the brain.

Nutrition Science: A Deeper dive

The deeper divein nutrition in covered in the book, The Brain That Chooses Itself. Asummary of threeof the most salient points follows: Consider this list:

Part Six: Expanding Healthspan Through Social Interactions

The health effects of loneliness can be measured in all-cause mortality and can be compared to alcoholism, obesity and smoking more than 15 cigarettes per day [50, 51]. Persistent loneliness that is out of our control is clearly unhealthy. Limited solitude when we need/ desire alone time is also unhealthy. Medical and wellness providers from all professions will benefit from the following collection of science on the effects of social connectedness as related to health, wellness, and longevity. By engaging in diverse social connections that we choose, we may improve our psychological tolerance, cognitive performance and extend both our lifespan and healthspan. The research, mechanisms and relationships are summarized with references accordingly in the list below:

The U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Vivek Murthy in May of 2023 wrote, “Our epidemic of loneliness and isolation has been an underappreciated public health crisis that has harmed individual and societal health. Our relationships are a source of healing and well-being hiding in plain sight – one that can help us live healthier, more fulfilled, and more productive lives.” He continued to add the significance of limited social support by saying, “Given the significant health consequences of loneliness and isolation, we must prioritize building social connection the same way we have prioritized other critical public health issues such as tobacco, obesity, and substance use disorders. Together, we can build a country that’s healthier, more resilient, less lonely, and more connected.”

Part Seven: Optimized Healthspan Through Rest, Sleep and Play

By employing current science on rest, sleep, and play in the methods and manners that we choose [64], we may extend both our lifespan and healthspan. The research, mechanisms and relationships are summarized with references accordingly in the list below:

Sleep deprivation

There is really no good news, and very little surprising news to be found as we summarize and cite the effects of sleep deprivation on health and performance. Objective tests, biomarkers, and dynamic imaging all show detrimental effects.

The negative effects directly caused from sleep deprivation include:

Suppressed performance in cognition, metabolic, physical performance [77, 78]

Sleep – A deeper dive

Comprehensive coverage of sleep can be found in the book, The Brain That Chooses Itself. Four of the most significant points to consider include:

Conclusions

The Science of Choice Applied in Aging – A Deeper Dive

The second article in this two-part series will cover the science of choice in greater depth. For the purposes of this article, it will be stated that small changes often lead to habits. Habits often lead to identities. Adopting an identity can be positive and long-lasting. Evidence tells us that when we adopt an identity, we are more likely to make choices that are consistent with our identity. Meaning, start with, “I am a person who will”…and finish with these statements, as they are written, or worded as you prefer:

We now understand that adopting an identity for yourself is powerful. Again, we benefit most when we have autonomy and are making a choice. We opt-in. Choosing your identity does not mean an “alter ego” or another persona/personality. Dixon & Dweck [86] help us to see that adopting an identity can be accomplished by merely iterating a growth-mindset affirmation. Research has demonstrated that there are health benefits to be gained when one declares that they are, “a non-smoker” or “a person who eats healthy foods,” or “a runner,” or “an active person.” They have essentially branded themselves and will be more likely to make choices consistent with their brand.

Life includes many choices. Every time that you are faced with a health-based choice (nutrition, activity, rest, social and challenge/ extreme), you have the opportunity to follow your identity, or not. When the choice that you make agrees with your identity, this serves as a long-term reinforcer of your ultimate behavior. This concept is layered and deep, but very simply reinforces the brainbased connections that limit your temptations for donuts, alcohol or cigarettes, for example. You receive a very simple and reliable chemical reward for making “the right choice.”

Adopting an identity strengthens the connections of neurons and will make it more likely that you make that choice again in the future. Additionally, not having that donut, as time goes by, will reduce your desire for that which you had craved. It is important that you are aware of a few of the other powerful and most common strategies that can both get you – and keep you – on track. These principles, as identified by the study of human decision making and motivation known as behavioral economics, include gamification, commitment devices, habit stacking, temptation bundling, nudge/eliminating friction, and loss aversion. For more depth on these concepts, consider reading the second installment of this two-article series with the same primary title, yet subtitled Leveraging the Science of Behavioral Economics.

Providing patients with the autonomy to make their own decisions, a choice, from a base of evidence can be more powerful than a prescription, coercion, or forceful education. Giving each decision maker an identity, agency, and a role in their healthcare team can improve engagement and prove empowering. We expect three positive results from this reframed approach to wellness and healthcare. These include:

Improved self-efficacy, which has a powerful effect on most outcomes.

Elevated autonomy, which can provide a boost to most outcomes.

The permission to commit, to believe in a plan, which additionally can have a powerful effect on most outcomes.

I can change = self-efficacy I get to decide, my decision matters = autonomy I think this would be best = belief

There is a distinct difference between choices that we make with full autonomy (free choice) and those that we make with limited or a singular option (forced choice). When we have autonomy and free choice, selecting from a few options or deciding not to make a choice…we have less cognitive stress, and less stress experienced throughout the body (physiologic).

Perhaps with this pivot, we can help more people achieve wellness, and reduce the need for health care, reduce the length and incidence of disability, and feel more empowered to control how they age.

Disclaimer

The author is not recommending that the reader take risks or suggest patients take risks with your safety or health by engaging in, or increasing the dosage of, any extreme experience. Each person’s medical history, biologic tolerances, and psychosocial history should be considered before deciding on your own if an experience is both safe and healthy for you.

Competing interests:

The authors of this research declare no competing interest regarding this study.