Journal of Rehabilitation Practices and Research Volume 6 (2025), Article ID: JRPR-165

https://doi.org/10.33790/jrpr1100165Research Article

Exploring Sense of Community in a Blended Entry-Level OTD Program: Impact on Fieldwork Preparedness

Thomas J. Decker, EdD, OTD, OTR/L

Associate Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy, Drake University, Des Moines, Iowa, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Thomas J. Decker, EdD, OTD, OTR/L, Associate Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy, Drake University, Des Moines, Iowa, United States.

Received date: 11th March, 2025

Accepted date: 26th April, 2025

Published date: 28th April, 2025

Citation: Decker, T. J., (2025). Exploring Sense of Community in a Blended Entry-Level OTD Program: Impact on Fieldwork Preparedness. J Rehab Pract Res, 6(1):165.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

This qualitative study examined the lived experiences of entry-level Doctor of Occupational Therapy (OTD) graduates in a blended learning program, focusing on their perceptions of preparedness for Level II fieldwork. Using a phenomenological research design, data were collected through demographic surveys and semi-structured interviews with 12 graduates. Thematic analysis identified four primary influences on student experiences: (1) program culture, design, and structure, (2) instructor-specific style, (3) hands-on learning experiences, and (4) personal connection and interaction. Findings highlight the significance of faculty engagement, structured peer collaboration, and experiential learning in shaping students’ professional readiness. Furthermore, faculty accessibility, mentorship, and professionalism emerged as key factors in fostering confidence and clinical competence. While blended learning promotes self-directed learning, participants emphasized the need for intentional faculty involvement and immersive practical experiences to bridge the gap between online coursework and clinical application. These findings offer critical insights for optimizing blended OTD curricula to enhance student success, professional identity formation, and clinical preparedness.

Keywords: Blended Learning, Occupational Therapy Education, Fieldwork, Sense of Community, Qualitative Research, Professional Readiness, Faculty Engagement

Introduction

The profession of occupational therapy (OT) has historically required a master’s degree as the entry-level qualification. However, recent discussions and recommendations by the Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (ACOTE) originally proposed transitioning to an entry-level Doctor of Occupational Therapy (OTD) degree, with an initial target date of 2027, which was later delayed [1]. Despite this delay, the transition remains likely, necessitating further examination of how OTD programs prepare students, particularly within blended learning environments.

Blended learning models, which integrate online and in-person instruction, are increasingly common across health professions education [2,3]. While such models provide flexibility, they may also reduce opportunities for interpersonal engagement, peer interaction, and professional mentorship, all essential elements of clinical skill development in OT education [4]. Given the increasing reliance on hybrid models in OTD programs, it is imperative to examine how these delivery methods influence student preparedness, particularly for high-stakes fieldwork experiences. Fieldwork serves as a critical bridge between academic coursework and professional practice. According to ACOTE [1], Level I and Level II fieldwork must support the development of clinical reasoning, communication, and professional identity. However, the majority of existing research has focused on traditional, face-to-face master's programs, leaving a significant gap regarding the perceptions of students in blended-entry OTD programs [5]. Questions remain about how blended models influence readiness, engagement, and the development of essential therapeutic competencies. From the student’s perspectives.

This study explored the lived experiences of students in a blended OTD program, focusing on their perceptions of preparedness for Level II fieldwork. By examining how students navigate faculty relationships, hands-on learning, and peer interaction within a blended format, the study offers insight into program structures that support, or constrain, fieldwork readiness.

Framework Guiding the Study

This study was grounded in two intersecting frameworks: occupational justice and the Community of Inquiry (CoI). Occupational justice emphasizes equitable access to meaningful occupations and participation, including relational, experiential, and educational opportunities that support professional development [6]. In the context of blended learning, this framework prompts critical inquiry into whether students are equitably supported in developing the relational and clinical skills necessary for effective fieldwork and future practice.

The CoI framework [7] complements this ethical foundation by providing a pedagogical structure for understanding online and blended learning. CoI emphasizes three essential components: social presence, cognitive presence, and teaching presence, all of which shape how students engage with content, instructors, and peers. These components are particularly relevant in hybrid programs, where virtual and in-person learning must be thoughtfully integrated to ensure academic success and clinical readiness.

Together, these frameworks offer a comprehensive lens: occupational justice highlights equity and access, while CoI addresses the quality and nature of interaction. The interview guide and analysis strategy were developed using both frameworks as sensitizing concepts, allowing us to examine how students experienced access, engagement, and identity development within a blended-entry OTD program.

Fieldwork serves as a critical bridge between academic preparation and professional practice. As ACOTE [1] emphasizes, both Level I and Level II fieldwork experiences must foster clinical reasoning, communication, and competence. However, the growing prevalence of blended learning introduces new complexities in preparing students for these experiences. Most research to date has focused on traditional in-person master’s programs, with limited attention to how hybrid models influence students’ perceptions of readiness [5]. In this study, fieldwork readiness is defined as students’ confidence, clinical reasoning, communication, and adaptability in applying knowledge in real-world settings.

While blended models offer flexibility and access, they may simultaneously reduce opportunities for mentorship, experiential practice, and professional modeling,elements that are critical for developing therapeutic use of self and clinical decision-making [4]. The current study aimed to explore how students’ experiences in a blended-entry OTD program shaped their perceptions of readiness for Level II fieldwork, their sense of community, and their connection to faculty and peers. Insights from this work have direct implications for program design, instructional delivery, and institutional decisions related to equity and support within hybrid OT education models.

Study Need for a Sense of Community

A consistent theme in occupational therapy pedagogy is the value of community in shaping students’ emotional, academic, and professional development [8]. In blended and online environments, where face-to-face interaction is limited, the development of meaningful peer and faculty relationships becomes increasingly complex and increasingly important. Prior research in health professions education underscores the connection between students’ sense of belonging and their engagement, motivation, and academic success [8-10].

The hybrid delivery model used in this study’s OTD program created opportunities for flexibility but required students to navigate learning in relative isolation. As described by participants, informal peer networks and accessible faculty members were often what sustained their motivation and sense of identity within the program. These findings support existing calls for greater attention to social presence and community-building structures in blended curricula, as emphasized by the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework. Instructor presence, peer interaction, and collaborative activities have been found to reduce student isolation and enhance engagement in online learning [11,12].

While previous studies have explored the concept of community in traditional in-person learning environments, fewer have examined how a blended model alters students’ access to social and academic supports. This study contributes to that growing dialogue by capturing student reflections on the specific factors, such as consistency of teaching presence, opportunities for collaboration, and peer mentoring, that enabled or disrupted their sense of connection.

Gaps in the Literature

Although research on online and hybrid education continues to grow, there remains a lack of focused studies examining the unique dynamics of blended learning in occupational therapy programs, especially at the entry-level doctoral level. Blended learning models have become increasingly common in healthcare education, with research suggesting benefits such as accessibility and flexibility, but also raising concerns regarding engagement and clinical skill development [13-16]. While some studies support the efficacy of blended instruction, others highlight gaps in hands-on learning and the challenges of maintaining professional presence across virtual platforms. Despite the proliferation of hybrid programs, there remains limited empirical work examining how these models impact clinical preparedness in occupational therapy education. Much of the current literature emphasizes academic outcomes or general student satisfaction, but does not sufficiently explore the relational and identity-related aspects of blended education. This is particularly problematic in a field like OT, where therapeutic use of self, interpersonal communication, and clinical confidence are core components of competent practice [17-20].

While existing studies have evaluated community-building and engagement strategies in online education broadly, there is limited empirical work on how peer support, mentorship, and access to hands-on learning contribute to professional identity formation in blended OT programs. Researchers such as Shackelford and Maxwell [21] and Trespalacios and Rand [22] have noted the importance of perceived community in shaping learning outcomes in hybrid environments, but few have tied these dynamics directly to fieldwork readiness.

This study seeks to address those gaps by offering a nuanced, participant-informed account of how structural, relational, and instructional variables within a blended OTD program shaped students’ readiness for clinical practice. Informed by the Community of Inquiry and occupational justice frameworks, these findings add depth to the growing dialogue on hybrid learning and help define the conditions necessary for supporting equitable and transformative educational experiences in occupational therapy.

Fieldwork Education and Student Preparedness

Fieldwork education plays a pivotal role in occupational therapy training by connecting academic learning to clinical practice. As students transition into Level II fieldwork, they are expected to demonstrate clinical reasoning, adaptability, and interpersonal competence, skills developed through both didactic instruction and meaningful interaction with mentors. Prior research has identified student characteristics that influence fieldwork success, including emotional intelligence, self-efficacy, and adaptability [18,23,24].

However, these traits are not developed in isolation. Faculty mentorship, accessibility, and professional modeling are critical influences on professional identity development. Research on medical and allied health education underscores the role of faculty as ethical and pedagogical exemplars [20,25]. Students in blended OTD programs, who may engage with faculty less frequently in person, rely on structured and intentional mentorship to bridge the gap between theoretical learning and clinical application.

Despite the centrality of fieldwork, most studies on OT student preparation focus on traditional master’s programs. Very few examine how hybrid models influence student readiness for clinical practice or how programmatic structure and faculty behaviors affect the development of clinical reasoning, communication, and therapeutic presence. This study addresses that gap by capturing how students in a blended OTD program perceived their preparation for Level II fieldwork, highlighting the structural and relational factors that supported or constrained their professional growth.

Methods

Aim of the Study

This phenomenological study explored the lived experiences of entry-level Doctor of Occupational Therapy (OTD) graduates from a blended learning program, with particular focus on their perceptions of community, mentorship, and preparedness for Level II fieldwork. Using a 70/30 online-to-in-person delivery model, the program provided a hybrid educational structure in which students navigated academic content, faculty relationships, and clinical training in both virtual and immersive formats. This study sought to understand how these experiences influenced students’ perceptions of clinical readiness and professional identity. Rather than collecting quantitative fieldwork scores, the research prioritized rich, narrative data through in-depth interviews.

Research Design

This study employed a qualitative, phenomenological research design grounded in a Husserlian approach to understand the lived experiences of students in a blended-entry OTD program. Husserlian phenomenology [8] was selected for its emphasis on first-person perspectives and the uncovering of shared meaning through direct participant accounts without interpretive overlays. This design aligns with descriptive phenomenology, which seeks to bracket presuppositions to illuminate essential themes within participants’ experiences [26,27].

Participants and Recruitment

Twelve participants from 4 consecutive cohorts were recruited through purposive sampling from a single entry-level blended OTD program in the United States. To qualify, participants had to have (a) completed all academic coursework, (b) completed at least one 12-week Level II fieldwork experience, and (c) graduated from the program itself. Recruitment emails were sent via a university alumni database, with all eligible participants volunteering through a secure online sign-up form.

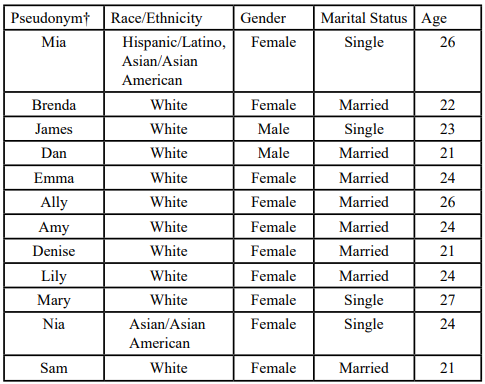

Participants represented variation in age, region, and educational background. This demographic diversity allowed for a fuller understanding of how blended learning is experienced across different learner profiles. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained prior to recruitment, and participants gave informed consent electronically (Protocol 2020-08-13-08-46). Table 1 provides a demographic overview of the 12 participants, including age, gender, marital status, and racial/ethnic background. All names are pseudonyms assigned to protect confidentiality.

Data Collection

Data were collected in two phases: first, through a demographic questionnaire that captured participant background; and second, through one-on-one, semi-structured interviews conducted via a secure video conferencing platform. Each interview lasted between 45 and 60 minutes and was audio recorded with permission and transcribed verbatim.

The interview guide was designed using principles from the CoI and occupational justice frameworks. Sample questions included:

• “How would you describe your experiences with online coursework in the OTD program?”

• “What factors influenced your sense of connection to peers and faculty?”

• “How do you believe your sense of community impacted your Level II fieldwork experiences?”

• “What challenges did you face in translating online learning into clinical practice?”

Follow-up probes explored moments of disconnection, mentorship, and student adaptation. Member checking was conducted by sending four participants summaries of their transcripts for confirmation of accuracy.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s [28] six-phase thematic analysis approach, framed within a phenomenological reduction process. This hybrid method allowed for inductive coding while also staying grounded in Husserlian principles of epoché, bracketing researcher assumptions to center the participants’ voices [26]. Transcripts were uploaded to NVivo software to facilitate coding and data organization.

The researcher coded the data and met regularly with a mentor to refine codes and resolve discrepancies through consensus. Thematic development followed these stages:

1. Familiarization with the data

2. Generation of initial codes

3. Searching for themes

4. Reviewing and refining themes

5. Defining and naming core experiential themes

6. Producing the final report with embedded participant quotations

This, consensus-driven approach promoted rigor while aligning with the philosophical tenets of phenomenology.

Trustworthiness

To enhance credibility and dependability, several strategies were employed:

• Member checking ensured thematic accuracy and interpretation.

• Audit trail documentation was maintained throughout the study to track analytic decisions.

• Reflexive memoing supported researcher awareness and bias mitigation.

• The individual coder and mentor shared consensus, thereby reducing interpretive drift and reinforcing rigor.

These strategies aligned with best practices in qualitative research and phenomenology, reinforcing confidence in the analytic process.

Ethical Considerations

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Nova Southeastern University. Informed consent was obtained electronically after participants reviewed details about study aims, risks, benefits, and confidentiality.

To protect participant anonymity, all names were changed and identifying details were removed from transcripts. Audio files were stored securely and deleted after transcription and verification. Participants were reminded of their right to withdraw at any time without consequence. These safeguards helped uphold ethical standards while honoring the potentially sensitive reflections shared during the interviews.

Results

Thematic analysis revealed four central themes based on participants’ descriptions of their experiences in the blended OTD program. This section presents those themes using participants' language and reflections, without interpretation. Illustrative quotes are included to demonstrate how each theme was articulated. While graduates across cohorts shared common experiences, notable differences emerged between earlier and later cohorts due to programmatic changes.

Theme 1: Program Culture, Design, and Structure

The first theme reflects how the larger structural environment, its clarity, consistency, and culture, impacted participants’ sense of belonging and readiness for clinical work. Participants described how the organization of the program, including curriculum delivery and course sequencing, influenced their engagement and confidence. Clear expectations and structured progression helped students stay on track, while inconsistencies in faculty roles and shifting course responsibilities sometimes disrupted learning. Dan [29] noted “So, the in-person visits were really important. And yeah, just the, you know, virtually being able to email or even call.”, while Denise (Class of 2019) pointed out that “There were times I didn’t know who to go to for what. Things changed between cohorts, and it made us feel like an afterthought.” And Ally (Class of 2019) stated that “Having a roadmap helped me know what was coming. When things felt thrown together, it was really frustrating.”

Several participants also noted that the culture shifted positively over time as new faculty brought a more student-centered ethos. Some participants described more frequent changes in instructional roles and less consistency in communication. Later cohorts noted incremental improvements in program structure and faculty responsiveness, suggesting that the experience of community evolved over time.

Theme 2: Instructor Style and Teaching Presence

Students emphasized the importance of consistent, responsive faculty. Instructors who were communicative and showed availability, built trust and confidence among students. Faculty presence, even in an online format, was identified as a stabilizing factor. Instructor engagement emerged as a critical influence on student confidence and identity formation. Instructor engagement was a critical influence on student confidence and professional identity formation, with responsive and consistent faculty described as creating stabilizing and empowering experiences. For example, James (Class of 2017) highlighted that “The ones who made time for us, who answered messages and checked in…..those were the professors who made a difference.” And Dan (Class of 2018) made a similar point: “Dr. K’s fieldwork visits reminded me that I wasn’t alone. That support really mattered.”

Conversely, a lack of feedback or inconsistent communication was cited as a barrier to learning. Participants emphasized that faculty behavior shaped not just academic success but also their professional identity. For instance, Lily (Class of 2019) stated, “Instructors who built relationships gave us a model of how to build them with clients later.” while Denise (Class of 2019) made the following point:

It really depends on the class I was taking or the setting that I was in, in terms of my Level II’s. And I will say that when it came to my pediatric rotation, I felt like that instructor was super available. So, I felt much more comfortable and confident going into that rotation.”

And another participant (Lily, Class of 2019) reflected more deeply on how instructor style shaped learning:

The faculty who stayed made sure we were doing okay. They built relationships that supported our learning… but you were really at the mercy of which instructor it was. I do better [with] positive feedback and humor, and some professors just had that.

Theme 3: Hands-On Learning and Experiential Practice

Students widely viewed in-person lab sessions and experiential learning as essential to developing clinical competence and clinical confidence. The opportunity to translate concepts into real-world application made learning more meaningful and boosted confidence in fieldwork settings. Thus, opportunities to apply concepts through physical interaction enhanced understanding of clinical reasoning and performance skills, as Amy (Class of 2019) remarked, “Practicing assessments in pediatrics helped me feel ahead of the curve in fieldwork.” However, several participants expressed that hands-on learning was not consistently embedded across courses, which they saw as a missed opportunity. For example, Denise (Class of 2019) remarked “I learn best by doing. Some classes nailed that, others were just lecture after lecture, and it didn’t stay with me.” And Brenda (Class of 2017) further highlighted, “The in-person labs made the content stick. I understood transfers and mobility better when we practiced them instead of just watching a video.” Furthermore, Emma (Class of 2018) noted, “I really needed the weekend immersions. That’s when it felt real. That’s when I felt like I was becoming an OT.” And Sam (Class of 2019) reiterated a similar point:

I feel like lab activities helped me a lot because that… is where the application comes in… I'm someone who could read and read…. I'm like, ‘what's the most important? Or what should I really be focusing on or thinking of how this applies?’

Theme 4: Peer Support and Relational Learning

Students consistently described peer relationships as essential for navigating challenges and managing the demands of the blended format. Informal peer groups provided encouragement, academic help, and emotional support. Furthermore, these relationships often compensated for gaps in faculty support or program structure, reinforcing the value of cohort-based collaboration and student initiated learning communities. For instance, Brenda (Class of 2017) said, “Honestly, my classmates were the ones who kept me going. We made our own community when it didn’t feel like the program had built one.” while Nia (Class of 2019) made a similar point: “We had group chats, Zoom study sessions, and check-ins. That connection helped me feel less alone.”

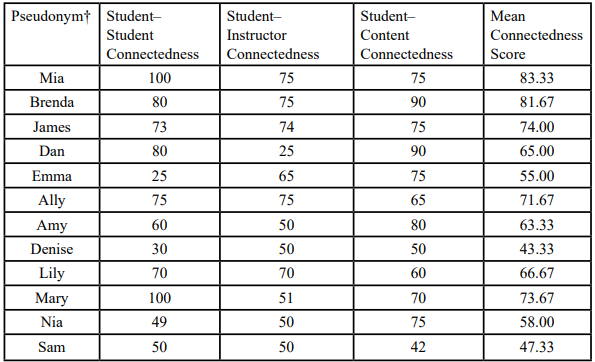

Participants’ reflections largely mirrored their self-rated connectedness scores, which consistently showed stronger bonds with peers and content than with faculty, highlighting the importance of intentional instructor presence. To further illustrate the relational dynamics, Table 2 presents participants’ self-rated levels of connection with peers, instructors, and course content.

Summary of Key Findings

• Blended learning and faculty-facilitated culture encouraged self-sufficiency but also required active student effort to build community.

• Faculty availability, personality style, and teaching style significantly impacted students’ sense of connection and preparedness.

• Experiential learning and hands-on opportunities improved students’ confidence and reported fieldwork success, but varied by instructor.

• Strong peer and faculty relationships were essential in navigating challenges across all cohorts.

Discussion

The findings of this study provide meaningful insights into the lived experiences of students in a blended OTD program and offer implications for both programmatic design and instructional delivery. These results are consistent with prior literature in health professions education that emphasizes the critical role of mentorship and experiential access, while also contributing new evidence about the challenges and strengths of community development in hybrid OT models. The four themes, program culture and structure, instructor presence, hands-on learning, and peer relationships, demonstrate that student preparedness for fieldwork is closely tied to the relational and structural dimensions of the educational experience.

Program Design and Equity

Variability in program structure and the impact of faculty turnover highlight the importance of transparent communication, equitable access to instructional resources, and consistent implementation of curricular design. These findings support the assertion that predictable programmatic scaffolding plays a foundational role in student confidence and academic success. This reinforces prior literature suggesting that uncoordinated instructional delivery may lead to confusion, inequity, and disengagement [30,31].

Instructor Presence and Professional Identity

Students’ reflections on faculty accessibility and mentorship speak directly to the CoI framework’s teaching and social presence components. Consistent engagement from faculty members was not only linked to greater emotional support, but were also described as critical to professional identity development. As Regehr and Eva [32] have argued, identity formation in health professions is rooted in interpersonal interaction. This study confirms that even in hybrid models, faculty visibility and responsiveness are integral to building students’ therapeutic use of self and confidence in their future role. Likewise, LaBarbera [11] emphasized the role of consistent instructor feedback and check-ins in sustaining social presence, and with Swick’s [20] model of faculty as moral and professional role models. Participants echoed these ideas, describing how faculty behavior influenced not just knowledge acquisition but also identity formation and ethical awareness.

Experiential Learning and Clinical Readiness

Students’ emphasis on lab-based, immersive experiences aligns with ACOTE’s emphasis on experiential learning and supports the continued use of in-person components to prepare for Level II fieldwork. These results reiteratethe points made by Istenic [33] and Lobos et al. [34], who argue that integrated practical engagement is essential in fostering authentic, real-world competence in hybrid education. The findings also reveal that inconsistent access to such resources across cohorts can create perceptions of unfairness, suggesting the need for structured equity in hands-on training opportunities. These results are also consistent with earlier literature [4,29], emphasizing the importance of applied, scenario-based learning in hybrid instructional design.

Peer Support and Community Building

The strong influence of peer relationships further highlights the need for intentional community-building strategies in blended learning environments. These informal networks not only supported students emotionally, but contributed to collaborative skill development essential for clinical practice. This reinforces the social presence domain of the CoI framework and aligns with Rovai [9] and Lewis et al. [12], who emphasize the necessity of building interpersonal connection in distributed educational settings. Although institutional efforts to foster peer engagement were limited, students actively created their own systems of support. These grassroots networks filled relational gaps and helped students develop emotional resilience and a sense of accountability to one another. This underscores the importance of formalizing opportunities for connection early in blended programs to avoid reliance solely on informal structures.

Sense of Isolation and Institutional Support

While many participants expressed a strong sense of belonging, some reported feelings of isolation, particularly in earlier cohorts where faculty turnover and inconsistent program structure were more prevalent. Several participants suggested that structured opportunities for cross-cohort mentorship and increased inter professional education initiatives could mitigate these challenges. This aligns with findings from Ames et al. [35] and Rausch & Crawford [36], which highlight the risks of attrition and disengagement when institutional structures for community-building are weak or unevenly implemented.

Implications for OT Education

This study’s findings suggest several actionable strategies:

• Structured onboarding to foster early community connection, such as pre-term orientation activities with peer mentoring and faculty meet-and-greets

• Proactive faculty engagement through routine feedback cycles and regular discussion facilitation

• Formalized opportunities for experiential learning, such as scheduled simulation labs accessible to all cohorts

• Curricular consistency, communication transparency, and mentorship prioritization to ensure equitable and effective student development

The use of the CoI and occupational justice frameworks provided a meaningful lens through which to understand the relational and ethical implications of program structure. These themes contribute to the broader literature on blended education in health professions by affirming the interplay between student experience, instructional practice, and clinical readiness. They also support growing calls for more robust, human-centered approaches to hybrid curricular design.

Limitations and Future Research

As with all qualitative research, the findings of this study are contextually bound and reflect the experiences of a specific group of students from one blended-entry OTD program. The use of purposive sampling limited the participant pool to those who were willing and able to share their perspectives, which may have excluded voices with differing experiences. Furthermore, participants were interviewed after graduation and may have experienced recall bias or reinterpretation of events through a post-program lens. While member checking was used to ensure transcript accuracy, future research could expand credibility through longitudinal follow-up or triangulation with faculty perspectives or performance data.

Future studies might explore:

• Differences in experience between students who preferred hybrid learning vs. those enrolled out of necessity.

• The impact of full-time employment on engagement and preparation.

• How non-cohort-based online programs structure social presence.

• How underrepresented or minority students experience belonging and preparation across hybrid formats.

• Faculty development models that prioritize mentorship, instructional presence, and applied teaching strategies

• The influence of interprofessional education in blended curricula on readiness for collaborative practice

Conclusion

This study adds to the growing body of research on hybrid and blended learning models in occupational therapy education by capturing students’ perceptions of support, preparedness, and connection. Findings demonstrate that readiness for Level II fieldwork is shaped by a constellation of factors - faculty consistency, equitable access to hands-on learning, and meaningful peer and instructor relationships - that must be intentionally designed and supported. By applying the frameworks of Community of Inquiry and occupational justice, this research highlights the importance of equity, mentorship, and presence across all instructional formats. These insights have direct implications for faculty, curriculum developers, and accreditation bodies seeking to enhance the quality and inclusivity of blended OT education. For example:

• Faculty can incorporate early feedback mechanisms and virtual office hours to improve social and teaching presence

• Curriculum designers can embed consistent, cohort-wide experiential modules to ensure equity

As programs continue to evolve, it is imperative that the student voice remains central in shaping approaches to instructional delivery and fieldwork preparation.

Competing Interests:

The authors of this research declare no competing interest regarding this study.

References

ACOTE. (2023). Accreditation standards for a doctoral level educational program for the occupational therapist. Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education. View

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2016). Online Report Card: Tracking Online Education in the United States. Babson Survey Research Group. Babson College, 231 Forest Street, Babson Park, MA 02457. View

Fuller, R., Joynes, V., Cooper, J., Boursicot, K., & Roberts,T. (2020). Could COVID-19 be our 'There is no alternative' (TINA) opportunity to enhance assessment? Med Teach. Jul; 42(7):781-786. View

Simonson, M., Smaldino, S., & Zvacek, S. (2015). Teaching and learning at a distance: Foundations of distance education (6th ed.). Information Age Publishing. View

Zeldenryk, L., & Bradey, S. (2013). The flexible learning needs and preferences of regional occupational therapy students in Australia. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(2), 314-327. View

Wilcock, A. A., & Townsend, E. (2019). Occupational justice. In Occupational therapy and health promotion (pp. 31–42). Wiley-Blackwell.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2–3), 87–105.View

Berry, S. (2017). Building community in online doctoral classrooms: Instructor practices that support community. Online Learning, 21(2), 227–245.View

Rovai, A. P. (2002). Building sense of community at a distance. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 3(1), 1–16. View

Paul, J. A. & Cochran, J. D. (2013). Key interactions for online programs between faculty, students, technologies, and educational institution. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 14(1), 49-62. View

LaBarbera, R. (2016). The importance of social presence and instructor immediacy in online learning environments. Journal of Instructional Research, 5, 39–42.

Lewis, L., Coursol, D. H., & Khan, L. (2015). The role of social presence, cognitive presence, and teaching presence in community building in distance education courses. Online Learning Journal, 19(3), 66–78.

Akhmetzyanova, A. I. (2023). Analysis of pedagogical practices in occupational therapy: Enhancing professional intelligence in students. Education Sciences, 13(2), 124.

Brown, L. D., & Bright, D. K. (2025). Service learning: Meaningful community-centered professional skill development for occupational therapy students. Journal of Occupational Therapy Education, 9(1).

McCutcheon, K., Lohan, M., Traynor, M., & Martin, D. (2015). A systematic review evaluating the impact of online or blended learning vs. face-to-face learning of clinical skills in undergraduate nurse education. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(2), 255-270. View

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2010). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. US Department of Education. Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development. Policy and Program Studies Service. ED-04-CO-0040View

Bonsaksen, T., Yazdani, F., & Ellingham, B. (2023). Impact of medical improvisation on therapeutic use of self in occupational therapy education. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(1), 7901205120.

Brown, T., Williams, B., & Etherington, J. (2016). Emotional intelligence and personality traits as predictors of occupational therapy students' practice education performance: A cross sectional study. Occupational Therapy International, 23(4), 412-424.View

Carstensen, T., Yazdani, F., & Bonsaksen, T. (2024). Therapeutic-use-of-self as relational pedagogy in occupational therapy education. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy.

Swick, H. M. (2000). Toward a normative definition of medical professionalism. Academic Medicine, 75(6), 612–616. View

Shackelford, J. L., & Maxwell, M. (2012b). Sense of community in graduate online education: Contribution of learner-to-learner interaction. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(4), 228-249. View

Trespalacios, J., & Rand, J. (2015). Using asynchronous activities to promote sense of community and learning in an online course. International Journal of Online Pedagogy and Course Design, 5(4), 1-13. View

Andonian, L. (2013). Emotional intelligence, self-efficacy, and occupational therapy students’ fieldwork performance. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 27(3), 201–215. View

Grenier, M. L. (2015). Facilitators and barriers to learning in occupational therapy fieldwork education: Student perspectives. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69(Suppl. 2), 6912185070p6912185071-6912185079. View

Cruess, S. R., Cruess, R. L., & Steinert, Y. (2019). Supporting the development of a professional identity: General principles. Medical Teacher, 41(6), 641–649. View

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Sage. View

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage. View

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. View

Dunlap, J. C., & Lowenthal, P. R. (2018). Online educators’ recommendations for teaching online: Crowdsourcing in action. Open Praxis, 10(1), 79–89. View

Curran, V. (2014). Faculty development initiatives designed to promote leadership in medical education: A BEME systematic review. Medical Teacher, 36(6), 469–477.

Sareen, A., & Mandal, R. (2024). Instructional scaffolding in health education: The role of program coherence. Health Professions Education Journal, 10(1), 45–54. View

Regehr, G., & Eva, K. (2006). Self-assessment, self-direction, and the self-regulating professional. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 449, 34–38. View

Istenic, A. (2024). Reframing blended learning in health professions education: A conceptual update. Medical Education, 58(1), 15–26.

Lobos, K., Reyes, F., & Watson, C. (2024). Engagement and self-regulated learning in hybrid environments: Implications for health education. Journal of Allied Health Education, 53(2), 102–118.

Ames, C., Berman, R., & Casteel, A. (2018). A preliminary examination of doctoral student retention factors in private online workspaces. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 13, 79–107. View

Rausch, D. W., & Crawford, E. K. (2012). Cohorts, communities of inquiry, and course delivery methods: UTC best practices in learning—the hybrid learning community model. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 60(3), 175–180. View