Journal of Rehabilitation Practices and Research Volume 6 (2025), Article ID: JRPR-184

https://doi.org/10.33790/jrpr1100184Research Article

Are Occupational Therapy Programs Doing Enough to Prepare Occupational Therapists to Address the Psychosocial Needs of Stroke Survivors?

Hailey Mulcahy, OTD, Jolie Handler, OTD, OTR/L, David Martin, OTD, Priscilla Aluko, OTD, OTR/L, and Lisa Knecht Sabres*, DHS, OTR/L,

Department of Occupational Therapy, Midwestern University, Downers Grove, IL., United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Lisa Knecht-Sabres, DHS, OTR/L, Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy, Midwestern University, 555 31st Street, Downers Grove, IL 60515, United States.

Received date: 04th July, 2025

Accepted date: 23rd September, 2025

Published date: 25th September, 2025

Citation: Mulcahy, H., Handler, J., Martin, D., Aluko, P., & Knecht-Sabres, L., (2025). Are Occupational Therapy Programs Doing Enough to Prepare Occupational Therapists to Address the Psychosocial Needs of Stroke Survivors?. J Rehab Pract Res, 6(2):184.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Purpose: Strokes are one of the leading causes of long-term disability in the United States. Unfortunately, over a third of stroke survivors face post-stroke depression and/or a plethora of psychosocial challenges that can affect their overall recovery and quality of life. This study investigated how occupational therapists (OTs) address the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors and identified barriers to effective intervention.

Methods: A sequential explanatory design was used to collect both quantitative and qualitative data. Purposeful, convenience, and snowball sampling were used to recruit participants for this study. 84 OTs completed an electronic survey, and 14 OTs participated in a focus group or individual interview. Rigor was enhanced through peer debriefing, expert review, respondent validation, and data triangulation. Quantitative data was analyzed with descriptive statistics, while qualitative data underwent thematic analysis.

Results: Survey results showed the majority of OTs in this study (66.7%) disclosed that they do not formally screen or complete an evaluation of a patient’s mental health and psychosocial needs following a stroke. 53% of participants felt slightly prepared and only 4% felt prepared in addressing the mental health/psychosocial needs of their patients. Three themes were identified from the qualitative data: (1) Sense of self is significantly impacted after having a stroke, (2) Numerous barriers impact OT’s ability to address psychosocial concerns, (3) Therapeutic use of self and establishing rapport is critical to identifying and addressing psychosocial needs and concerns.

Conclusion: The findings suggest that OTs are not fully meeting the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors due to a variety of barriers. This study also suggests that OT Programs may need to better educate and train students in their ability to address the psychosocial needs of patients with physical dysfunction. Additionally, these findings may suggest that if further education and training regarding this topic was mandated for practicing therapists, that this might facilitate the ability of practicing occupational therapists to better address the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors. Future research investigating this topic would be beneficial.

Keywords: Occupational Therapy Education; Occupational Therapy Practice; Psychosocial Needs; Stroke Survivors; ACOTE Standards

Introduction

Strokes are one of the leading causes of death and long-term disability in the United States [1]. Following a stroke, individuals can experience post-stroke depression or anxiety that can affect their overall recovery [2]. In fact, approximately 33-40% of stroke survivors experience post-stroke depression (PSD) [3]. Depression often results in greater disability to the client and can impact motivational levels, functional recovery, and lead to increased burden on the family or other caregivers [4]. High levels of depression in stroke survivors are also associated with greater rates of disability, cognitive impairment, higher mortality rates, and overall reduced quality of life [5]. However, despite the high rates of post-stroke depression and anxiety, post-stroke care often focuses on the physical, cognitive, and sensory effects of the stroke and neglects to address the emotional and psychological ramifications of the stroke [6]. Due to the prevalence of post-stroke depression and other emotional and psychological disorders, it is essential for occupational therapists and other health care professionals working with stroke survivors to consider an approach that promotes mental well-being through interventions that address depression, anxiety, or mental-health related quality of life.

Common Consequences of Strokes & Impact of Stroke on Roles and Occupations

Individuals often experience a variety of challenges after a stroke, including a variety of physical, medical, cognitive, sensory, linguistic, and psychosocial difficulties [7]. Psychosocial complications can include post-stroke depression and mood/emotional changes which can be directly related to the stroke or can stem from the individual’s reaction to dealing with the multiple life changing effects of the stroke [7]. Post-stroke depression is the most common psychiatric disorder that happens after experiencing a stroke [5]. The social impacts of a stroke include having fewer social activities, decreased participation in leisure activities, social isolation, and a disruption in family life [8]. Northcott et al. also points out that a stroke not only impacts the stroke survivor, but their family and friends as well [8]. Moreover, the ramifications of a stroke can lead to life altering circumstances such as lost abilities to fulfill roles within the family and loss of ability to participate in shared activities. Additionally, loss of employment is another issue individuals may face post-stroke. More specifically, research has found that those who are unable to return to work have higher levels of unmet needs and poor psychosocial outcomes [9]. Moreover, loss of employment can affect not only the stroke survivor, but their families or carers [9]. Additionally, O’Sullivan and Chard revealed that strokes often result in a decreased ability to engage in a variety of active leisure pursuits (e.g., walking, gardening, visiting with friends, activities in the community, volunteer work, etc.) [10]. These restrictions have led stroke survivors to participate in more sedentary and solitary leisure activities (e.g., reading, watching TV, and talking on the phone) which has been associated with isolation and a variety of psychosocial issues [10].

Stroke survivors experience residual physical, cognitive, psychosocial, and behavioral challenges that can affect occupational engagement [11,12]. That is, strokes can impact one’s ability to fulfill their role as a spouse, parent, worker, or friend. Occupations that can be impacted by a stroke include activities of daily living (ADLs), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), work, and leisure activities [13]. Strokes can also cause a disruption in sleep which can further impact one’s occupational performance [14]. Wenzel et al. revealed that stroke survivors experienced impairments from their stroke that made it difficult to participate in their valued roles and occupations, and in some cases, they lost their ability to engage in some of their most valued roles and occupations [6].

Patient Perspectives on Post-Stroke Care

Wenzel et al. revealed that even though stroke survivors experienced many different feelings and emotions following a stroke, their psychosocial needs were often not addressed in therapy [6]. For instance, research shows that existing stroke rehabilitation methods focus primarily on maximizing physical recovery for survivors. Incorporating support for achieving psychosocial recovery remains underdeveloped in current rehabilitation services, which are largely guided by the biomedical model of care [15]. Moreover, stroke survivors have expressed that they are not likely to initiate discussions or disclose their state of mental health to their therapists [6]. Furthermore, stroke survivors exposed that they assumed if they brought these types of concerns to the attention of healthcare professionals, they would either not listen to their concerns or diagnose them with depression [16]. Additionally, the stroke survivors articulated that they were unaware that health professionals, such as occupational therapists, were able to evaluate and treat the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors [6].

Wenzel et al. afforded an opportunity for stroke survivors to provide suggestions to healthcare professionals so that they can better address their psychosocial needs [6]. In this study, the stroke survivors recommended involving family and caregivers more often in therapies to enhance their care, social support post-discharge, and to better prepare for their return home [6]. Unfortunately, Stott et al. found that stroke survivors felt isolated while receiving services and reported feeling that the healthcare professionals did not have the time, knowledge, and resources to better help them.16 Hodsen et al. found that the emotional and psychosocial changes not only impact the survivor, but can impact others around them, such as their spouse. Thus, they asserted that additional support is needed for sequel emotional and behavioral changes after a stroke [17].

Peer support groups offer hope to return to meaningful occupations, a place of belonging, problem-solving, and finding a purpose beyond oneself [18]. However, the lack of education and resources on psychosocial needs after discharge resulted in stroke survivors finding support groups independently [6]. Stroke survivors also expressed that it is important for therapists to acknowledge that clients have losses [6]. Furthermore, they also conveyed that helping them get back to meaningful activities, as well as enhancing leisure and social participation during and after occupational therapy is essential to their well-being [6].

Unmet Needs of Stroke Survivors

Unmet needs have had various different meanings throughout time. Zawawi et al. defined unmet needs as, “a problem that was not being addressed or one that was being addressed but insufficiently” (p. 2) [19]. Stroke survivors have reported a variety of unmet needs during rehabilitation and grouped their unmet needs into four categories: (1) physical and other stroke-related problems; (2) social participation; (3) information; and (4) rehabilitation and care [19]. Within these four categories, they each have many types of unmet needs which can be further classified into various aspects of unmet needs. Some aspects of unmet needs for physical and other stroke-related problems that were reported by stroke survivors include physical, cognitive and emotional functions. For social participation, support in living, community re-integration, and relationships were amongst some that stroke survivors reported [19]. Related aspects for information were found to be stroke related information, information on post stroke care and rehabilitation, and information on being productive and continuing living after stroke [19]. Stroke survivors had also reported unmet needs with receiving rehabilitation services such as occupational therapy and needing some help with their home care. These unmet needs extend from community re-integration to their physical, cognitive, and emotional functions. Individuals returning to their community have a hard time coping with transition from the hospital, back to where they were living [20]. Wenzel, et al. also revealed that stroke survivors feel their psychosocial needs are not addressed by their healthcare professionals, even though they experience residual physical, cognitive, psychosocial, and behavioral challenges [6].

The Role of OT in Addressing the Psychosocial Needs of Stroke Survivors

OTs play an important role in addressing the psychosocial needs of their clients. They view the person as a whole, considering their physical, emotional, social, and environmental factors [11]. OTs understand the importance of social support and encourage clients to engage in social activities and networks [4]. They may also provide education and resources to family members and caregivers to support their loved one’s psychosocial needs. Furthermore, OTs are skilled at identifying ways to promote self-esteem, self-confidence, and positive self-image, as well as developing coping strategies and resilience [21]. Overall, OTs take a holistic approach to addressing the psychosocial needs of their clients, recognizing that mental health and well-being are crucial components of overall health and quality of life [6]. Due to the plethora of unmet needs of stroke survivors, OTs can play an integral role in facilitating the transition from being a stroke survivor to an individual who is able to lead a meaningful life in the community. In fact, Madhoun et al. provided evidence that individuals who received occupational therapy services post stroke had improved functional performance as well as a reduced risk for poor health outcomes [22]. Likewise, Duxbury et al. showed that outpatient or home health services after discharge have been identified as an effective part of rehabilitation for stroke survivors [13].

Addressing Psychosocial Needs through Educational Preparedness

The Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (ACOTE) is the governing body that establishes and approves the educational standards that OT and OTA programs follow. Within these standards, it requires that occupational therapists should be able to plan and apply OT interventions that address a variety of needs, including psychosocial needs in a variety of contexts and environments [23]. Compared to the 2011 ACOTE standards, the 2018 ACOTE standards changed the preexisting standard C.1.3. to ensure that fieldwork objectives included a psychosocial objective for every fieldwork experience [24]. Despite the addition of including psychosocial objectives for all fieldwork experiences in the 2018 ACOTE standards, the literature shows that OTs are continuing to focus on the physical needs over the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors [6]. Moreover, Simpson et al. provided evidence that even though the majority of OTs considered their clients' mental health needs to be a priority, only a little over half of the therapists were satisfied with the care they provided regarding their clients’ mental and emotional health [2]. Since Simpson et al. identified a variety of barriers to the provision of mental health services to clients post stroke, with one of the noted barriers being poor educational preparation, [2] one of the aims of this study is to investigate if recently trained occupational therapists (i.e., therapists who graduated from an OT academic program which implemented the 2018 ACOTE Standards) are better at addressing the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors, compared to therapists who were taught under the ACOTE Standards prior to 2018.

Since it is estimated that 33.3% of the stroke survivors eventually develop post-stroke depression (PSD), [25] OTs need to be prepared to assess and address the mental health impairments of stroke survivors to maximize the benefits of rehabilitation. Thus, an additional purpose of this study was to gain a better understanding of how occupational therapists are addressing the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors, as well as the barriers which may be inhibiting their ability to fully address the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors. This need led to the following research questions: (1) How are occupational therapists addressing the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors? (2) What are the barriers to being able to fully address the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors? (3) Are therapists who were educated with the 2018 ACOTE Standards better able to address the psychosocial needs of their stroke survivors, compared to therapists who were taught under the ACOTE Standards prior to 2018?

Methods

Research Design

A sequential explanatory design was intentionally chosen for this study to allow for a more thorough understanding of the occupational therapist’s perspective of psychosocial needs of stroke survivors and how it has affected their life satisfaction and well-being [26]. Quantitative data was collected first through the use of electronic surveys. Then, the researchers collected qualitative data via the use of interviews and focus groups. This second phase of data collection helped explain and expand the quantitative findings. Finally, true to a mixed methods design, both the quantitative and qualitative results were analyzed to interpret the connected results from both sets of data. Thus, this research design allowed the researchers to bring together both sets of data so they can be compared and combined. This study was approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained from the participants before any data was gathered.

Recruitment and Participants

Purposeful, convenience, and snowball sampling were used to recruit participants for this study. More specifically, to recruit survey participants, the researchers sent invitations to participate in this study via emails to therapists through state OT associations, licensing lists, hospital distribution lists, and through professional acquaintances of the researchers. Posts were made on the American Occupational Therapy Association’s open online forum. Additionally, all participants were asked to forward the survey information to other professional contacts who met the inclusion criteria. In order to recruit participants for the focus groups and/or individual interviews, the survey offered an opportunity to partake in focus groups. Since the survey was anonymous, the researchers asked interested focus group participants to email or call the researchers for scheduling purposes. According to Redcap data, 37 people indicated that they were interested in participating in a focus group; however, only a handful of survey participants followed through with contacting the researchers to participate in a focus group. Thus, the researchers enhanced recruitment measures by sending invitations to participate in the focus group by emails to therapists via state OT associations, licensing lists, hospital distribution lists, and through professional acquaintances of the researchers. Specifically, 7.7% of participants indicated they learned about the focus group through the survey, 30.8% were invited via professional acquaintances, 15.4% heard about it through word of mouth, and 46.2% of participants did not specify how they became interested in joining the focus group.

Inclusion Criteria

In order to participate in this study, participants needed to: (1) be an OT with at least 1 year of experience and someone who primarily works with stroke survivors and (2) be able to read, speak, and understand English. The researchers recruited 84 participants for the survey and 14 participants for the focus groups.

Data Collection

Quantitative data was obtained via a researcher-developed online survey. The survey was created on Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a secure online software developed for research purposes. The survey collected quantitative data via the use of closed-ended questions (n = 14) and qualitative data through the use of an open ended (n = 1) question (Appendix A). The survey questions were aimed at gathering information regarding addressing mental health needs of stroke survivors, including the form of post-stroke education and resources they provide to their patients and clients, and their comfort level of addressing these needs. Additionally, the survey inquired about the participant’s preparedness for addressing psychosocial needs and the obstacles they encounter in addressing their patients' and clients' mental health, as described by the OT participants.

In addition to the quantitative data collected from the surveys, the researchers gathered qualitative data from semi-structured focus groups. The researchers conducted four focus groups and one individual interview consisting of participants with varying levels of experience based on graduation time either prior or after implementation of the 2018 ACOTE standards. Two groups had therapists educated under 2018 ACOTE standards (n=3; n=2) and two focus groups (n=5; n=3) and one individual interview (n=1) consisted of therapists educated before the implementation of the 2018 ACOTE standards. Each focus group lasted between 60 to 90 minutes. With the participants’ consent, each focus group was audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The researcher-developed survey and semi-structured focus group questions were informed by the literature and revised according to one expert in mental health, one expert in physical dysfunction and neurorehabilitation, and two experts in OT research. The final compilation of focus group questions was modified as appropriate based on the results of the survey responses. Ultimately, the focus group questions were used to guide topics and to spark conversation about the experience of working with stroke survivors and how the participants address psychosocial needs in their clients. A few topics that the researchers had discussed with focus group participants included if they formally screen for mental health needs, the mental health challenges clients face, the level of comfort they feel in addressing psychosocial needs, how they prepare clients for life after discharge, signs of distress related to mental health challenges observed with stroke survivors, and how they facilitate re-integration into the community. (please see Appendix B for examples of focus group questions).

Data Analysis

The quantitative data obtained from the survey responses was analyzed with descriptive statistics. Qualitative data from the focus groups was analyzed for themes [17]. Researchers individually coded all of the qualitative data and then cross-checked codes for inter-coder agreement. Re-coding of data occurred until consensus was reached. To enhance trustworthiness of findings, peer debriefing and expert review were implemented throughout the data collection and analysis process. Additionally, informant feedback (respondent validation/member checking) was used to enhance the accuracy and trustworthiness of the findings. This occurred by emailing a summary of the findings to participants after the completion of the qualitative data collection. Member checking also gave the participants another chance to offer any additional thoughts regarding this topic. True to a sequential explanatory design, the researchers compared and contrasted both quantitative and qualitative findings during the data analysis and interpretation process. Thus, rigor and trustworthiness of the results were enhanced by triangulation of the data. Finally, the findings from this study were also compared with the existing literature.

Results

Quantitative Data

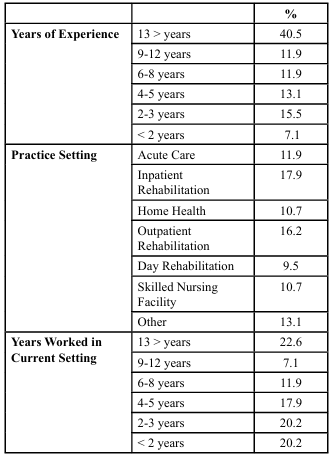

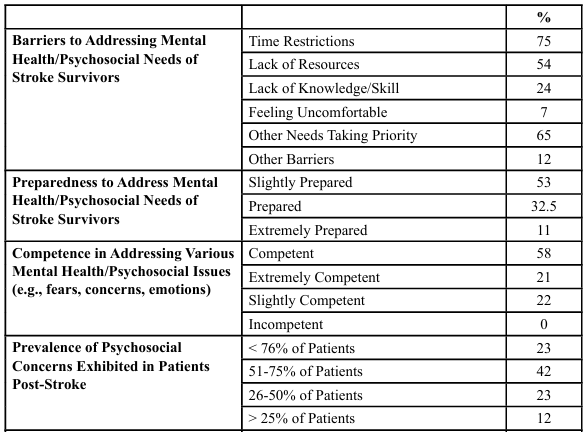

Eighty-four OTs completed the online survey. Additional demographic information about the participants is presented in Table 1. The majority of therapists in this study (66.7%) indicated that they do not formally screen or evaluate stroke survivors' mental health and psychosocial needs due to various barriers, such as discomfort with addressing these issues, time constraints, lack of resources, and/or lack of knowledge regarding existing resources (e.g., screening tools and standardized assessments). Many therapists (59.5%) believed that other professionals are better suited to handle these concerns. A small percentage provided educational materials and referrals to mental health specialists, and a few offered additional resources such as psychosocial group sessions. Additional information on participants’ responses is presented in Table 2.

Qualitative Data

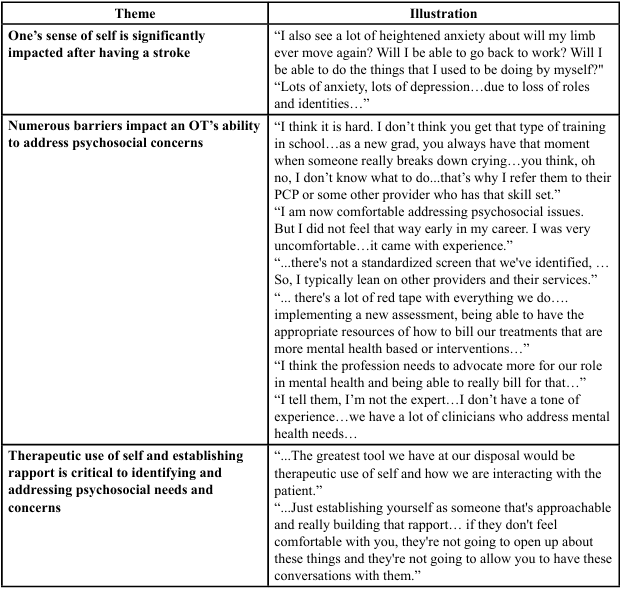

The occupational therapists’ perspective on addressing psychosocial needs and the associated barriers were illuminated through the insights gained from the focus groups. Three major themes were derived from the qualitative data analysis: (1) one’s sense of self is significantly impacted after having a stroke; (2) numerous barriers impact an OT’s ability to address psychosocial concerns; and (3) therapeutic use of self and establishing rapport is critical to identifying and addressing psychosocial needs and concerns.

Theme 1: One’s Sense of Self is Significantly Impacted After Having a Stroke

Participants in the study recognized that strokes often profoundly impact an individuals' sense of self and their self-identity. They expressed that these changes often led to psychosocial issues such as depression and anxiety; furthermore, they shared that when this is compounded by a diminished sense of self-efficacy it frequently hinders one’s engagement in daily activities and other meaningful pursuits. The participants also asserted that mental health challenges reduce motivation and independence, fostering fear and frustration about returning to independent tasks. Participants emphasized occupational therapy's role in identifying and reshaping goals, priorities, and expectations post-stroke. Please refer to Table 3, which highlights some of the key quotes related to this theme.

Table 2: Participants’ Perception Related to Mental Health/Psychosocial Needs in Stroke Survivors (N = 84)

Theme 2: Numerous Barriers Impact an OT’s Ability to Address Psychosocial Concerns

Participants acknowledged the importance of addressing psychosocial concerns in their patients; however, they identified a variety of barriers hindering their ability to address these issues. Many participants expressed that being able to prioritize the psychosocial needs of their patients and clients was not fully supported by their organization or healthcare system. However, the participants, especially the newer graduates, also expressed that they felt ill-prepared to address their patients’ psychosocial needs. In fact, many participants expressed that other health care professionals such as primary care physicians, social workers, and psychologists were better able to address their patients’ mental health and psychosocial needs. Numerous participants mentioned the lack of standardized assessments and/or lack of knowledge regarding formal screening tools and assessment tools available for OTs to utilize with their patients resorting them to informal assessments or relying on using their therapeutic use of self to meet these needs. Due to the lack of resources available to the OTs, participants expressed a belief that professionals from other fields are better equipped to address psychosocial needs as they have resources readily available within their professions. Additionally, participants found difficulty in understanding how to be able to bill for services when they were specifically addressing their patients’ psychosocial needs. Please refer to Table 3, which highlights some of the key quotes related to this theme. Based on these barriers, four subthemes were created. These subthemes were categorized as: (1) organizational barriers; (2) lack of standardized assessments; (3) lack of knowledge, preparation and resources; and (4) reimbursement/billing issues.

Subtheme 1: Organizational Barriers

Participants indicated that organizational barriers directly affect the delivery of care and overall patient outcomes. For example, participants expressed that “... working with people post stroke, there's a lot of other priorities.” and the organization (e.g., rehabilitation setting) emphasizes “the need for OTs to focus on other priorities related to physical impairments and improvements.” They also noted that clients are overloaded with other tasks, such as consultations with other care providers and getting accustomed to life which hinders the ability to address their mental health needs. Furthermore, participants expressed that their organization directs them to focus more on the physical implications, following a bottom-up approach. Participants recognized that while mental health may not be explicitly addressed in formal expectations, there is an implicit understanding within the rehabilitation team of the value of occupation and its potential impact on addressing mental health needs.

Subtheme 2: Lack of Standardized Assessments

Participants expressed the lack of formal assessments for mental health and psychosocial needs and/or a lack of knowing what type of assessments are available to address these needs. One participant had stated, “the screening tool is a really good idea. I wish we had something.” Many participants do not use formal assessments during evaluations or conduct informal assessments. Their main concern was the lack of a formal and standardized screening process that could be consistently relied upon. One participant reflected on the informal nature of their approach stating, “...we don't formally screen, it's more informal, just, how are you doing?”

Subtheme 3: Lack of Knowledge, Preparation, & Resources

The participants in this study expressed significant challenges in addressing the psychosocial needs of their patients due to a variety of factors such as lack of knowledge, training, experience, and due to a lack of resources. Some of the participants expressed that they didn’t get any training in OT school that provided guidance, experience, and practice dealing with the psychosocial needs of patients with physical dysfunction. They expressed that their lack of skill, comfort, and confidence resulted in not directly addressing their patients’ mental health and psychosocial needs and often resulted in a referral to other healthcare professions such as social workers, physicians, and psychologists. However, some of the participants with vast experience in the profession indicated that they are now comfortable addressing their patients’ psychosocial issues, but it took a lot of time and experience to get to that point. Some participants shared that inadequacies such as limited (private) space also impacted their ability to address some of their patients’ psychological needs.

Subtheme 4: Reimbursement/Billing Issues

Participants expressed a need for established billing procedures tailored to mental health services, with one participant stating, "Being able to have the appropriate resources on how to bill our treatments that are more mental health-based interventions is something that we’ve been struggling with." Uncertainty persisted regarding which aspects of treatment sessions could be billed and reimbursed when addressing psychosocial needs. One participant shared, "...it’s hard as a therapist sometimes because you think in the back of your mind that’s not billable time.” Another participant expressed a desire for the profession to advocate more strongly for our role in mental health because this will enhance our ability to bill for therapy services specifically designed to address psychosocial needs.

Theme 3: Therapeutic Use of Self and Establishing Rapport is Critical to Identifying and Addressing Psychosocial Needs and Concerns

Participants highlighted the effectiveness of therapeutic use of self as a way to build rapport with their patients. One participant explained the viewpoint of a patient, “...they want to feel cared for just beyond being like a patient.” Moreover, the participants asserted that establishing rapport with a patient is imperative to being able to address the psychosocial needs and concerns of the patient or client. They explained that if the patient or client doesn’t feel comfortable with the therapist, they won’t open up and divulge their concerns and vulnerabilities. Participants explained it is important in “... meeting the patient where they are, obviously always reading the room and reading the tone of the room. Going slow, taking our time, making sure you know that we're doing what the patient wants to do…” Thus, they expressed the importance of being approachable and having open conversations to be able to identify and address the stroke survivor’s psychosocial needs and concerns (see Table 3).

Discussion

This study examined recent and more experienced occupational therapists’ perceptions of their ability to meet the psychosocial needs specific to stroke survivors and the barriers inhibiting their ability to fully address the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors. Since ACOTE enhanced the educational standards related to psychosocial occupational therapy practice in 2018, [23] another aim of this study was to investigate if there were any differences related to occupational therapists’ who were trained before and after the implementation of the 2018 ACOTE Standards.

The quantitative and qualitative results of this study support the current evidence and provide additional insight into understanding how occupational therapists are addressing the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors, and barriers inhibiting their ability to fully address their psychosocial needs. Studies have revealed that even though stroke survivors experience many emotions following a stroke, their psychosocial needs were often not addressed in therapy [6]. Similarly, the quantitative findings of this study revealed that over 50% of the survey participants indicated that they only felt slightly prepared to address the mental health and psychosocial needs of stroke survivors, while approximately 25% of the participants stated that they lacked the knowledge and 25% of the participants reported they felt only slightly competent in addressing the mental health and psychosocial needs of stroke survivors. Additionally, 42% of the survey participants indicated that they only occasionally discussed typical post stroke mental health/psychosocial changes with family and 36% only occasionally or never discussed typical post stroke mental health/psychosocial changes with their patients prior to discharge. Likewise, only approximately 40% of the participants provided resources regarding mental health specialists or educational handouts regarding mental health/psychosocial changes post stroke.

In terms of recognizing the importance of addressing psychosocial needs, the participants in this study frequently commented on how having a stroke significantly altered the individual’s sense of self as they acknowledged how strokes often result in the loss of roles, alterations in family dynamics, diminished sense of independence, as well as motivational changes in carrying out daily activities, all of which can lead to a plethora of psychosocial issues. The participants in this study also reported how the impact of having a stroke can lead to psychosocial concerns such as depression and anxiety which can negatively impact the process of recovery and quality of life. Furthermore, the participants highlighted the importance of therapeutic use of self and therapeutic rapport in the occupational therapy intervention process and asserted that these affective skills are critical to being able to identify and address the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors. These discoveries support the findings from previous research regarding how OTs address the mental health needs of clients post stroke in the neurorehabilitation settings [2]. However, similar to Simpson et al., participants in this study also expressed a variety of barriers in dealing with the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors [2]. For example, comparable to Simpson et al., the participants in this study expressed that issues such as time, organizational barriers, lack of standardized assessments and/or knowledge regarding available assessments, lack of resources, lack of knowledge and skills, and reimbursement/billing issues impacted their ability to fully address the psychosocial needs of individuals after a stroke [2]. Moreover, Wenzel et al. exposed that stroke survivors were reluctant to share their mental health issues with healthcare professionals and had a lack of awareness that occupational therapists could even address such concerns [6]. Our study echoed this sentiment, as occupational therapists indicated a preference for involving other healthcare professionals, such as social workers or psychologists, to address their patient’s psychosocial needs.

Even though the quantitative and qualitative data results displayed many similarities, the qualitative data provided additional insights to better understand this complex topic. For instance, the qualitative data indicated that not only did some of the therapists who graduated after the 2018 ACOTE Standards feel incompetent in addressing their patient’s psychosocial needs, but they felt that their lack of education and clinical experiences had a greater impact on their ability to address their patient’s psychosocial needs than the other listed barriers. Additionally, even though the majority of focus group participants reported that at least 50% of stroke survivors exhibited signs of post-stroke depression and/or anxiety, the majority of therapists also revealed that they do not formally screen or complete an evaluation of stroke survivors’ mental health and psychosocial needs post-stroke. These findings seem to suggest the need to provide better training and education regarding this topic, perhaps starting in the OT student’s didactic education and continuing after graduation. Since there is a dramatic difference between didactic education and application of knowledge and skills in the clinical world, perhaps, if further education and training regarding this topic was mandated for practicing therapists, this might facilitate the ability of occupational therapists to better address the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors. Thus, future research should specifically consider investigating this topic.

The findings also uncovered that graduating before or after the 2018 ACOTE standards does not impact the feelings and efforts in addressing psychosocial/mental health needs. Significant differences between groups were not revealed; however, the more experienced group of therapists expressed higher confidence levels in their ability to address the mental health needs of stroke survivors which they attributed to their amount of experience in the profession. Whereas the participants who graduated under the 2018 ACOTE standards, perhaps, who had more focus and formal education on mental health in their didactic coursework and in fieldwork education, lacked confidence in their abilities. Interestingly, though, these participants expressed that the more they developed the skill of being able to talk to their patients about mental health, the easier it was to address it in the moment with their patients (stroke survivors). This finding might suggest that more experiential learning opportunities related to this topic may be necessary in OT curriculums. As Knecht-Sabres revealed, experiential learning opportunities can be an effective method to enhance understanding and application of content and can improve professional skills [28,29]. Thus, perhaps, OT educators may need to assess and/or modify their educational approaches to ensure that their students are truly developing the skills and confidence in being able to address the psychosocial and mental health needs of their patients with physical dysfunction.

Implications for Practice

The results of this study have the potential to facilitate better outcomes related to the unmet psychosocial needs of stroke survivors by having OT educators assess if or how they are addressing the OT students’ knowledge and skills related to the evaluation and intervention of the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors. Even though the 2018 ACOTE Standards required that fieldwork objectives include a psychosocial objective for every fieldwork experience, the results of this study seem to suggest that therapists both before and after the implementation of the 2018 ACOTE standards continue to lack either the knowledge and/or skills to be able to fully meet the mental health needs of their patients in the clinical world. Although the new 2023 ACOTE Standards do include standards C.1.3 (which necessitates that OT academic programs “Document that all fieldwork experiences include an objective with a focus on the occupational therapy practitioner’s role in addressing the psychosocial aspects of the client’s engagement in occupation”) and standard C.1.6 (which requires OT academic programs to “Ensure at least one fieldwork experience (either Level I or Level II) has a primary focus on the role of occupational therapy practitioners addressing mental health, behavioral health, or psychosocial aspects of client performance to support their engagement in occupations”), these standards are very similar to 2018 ACOTE Standards C.1.3 (“Ensure that fieldwork objectives for all experiences include a psychosocial objective”) and C.1.7 (At least one fieldwork experience (either Level I or Level II) must address practice in behavioral health, or psychological and social factors influencing engagement in occupation). Thus, even though these standards are mandated to ensure minimal requirements for entry-level practice, the results of this study may suggest that educational programs may need to further address this topic in their academic programs. Additionally, perhaps, if further education and training regarding this topic was mandated for practicing therapists, this might also facilitate the ability of occupational therapists to better address the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors.

Strengths, Limitations, and Recommendations for Future Research

This study implemented numerous strategies to enhance the rigor and validity of the findings. To enhance rigor, researchers individually coded the qualitative data and cross-checked codes/ themes for inter-coder agreement. Peer debriefing and expert review was implemented throughout the data collection and analysis process. Informant feedback was also used to enhance accuracy and trustworthiness of the findings. Even though this study included occupational therapists with diverse backgrounds and varying years of experience in practice, it had a relatively small sample size, and the focus groups had slightly different representation related to the implementation of ACOTE educational standards during their didactic education. Thus, future research studies should include a larger sample size, participants from more diverse locations across the country, and students who were instructed with the current, 2023 ACOTE Standards. Future studies might also want to consider a more stringent inclusion criterion. For example, since the inclusion criteria for this study required OT practitioners to have at least 1 year of experience and someone who primarily works with stroke survivors, there could have been great variability regarding the amount of experience in this area of practice, which could have impacted the findings. However, even though it is possible that some of the participants were employed part-time versus full-time, over 50% of the participants in this study had over 9 years of experience in occupational therapy. While this study provided a good exploration of the occupational therapist’s perspective on addressing the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors, there remains considerable opportunity for further investigation into this topic. Additionally, a study simultaneously examining the perspectives of both therapists and clients may yield more precise and comprehensive information.

Conclusion

Strokes are the primary cause of disability in the United States and are among the prevalent conditions that are managed by occupational therapists. This study investigated the perspectives of occupational therapists, exploring their competence, comfort, and expertise in dealing with the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors. The study's findings suggested that occupational therapists may not be fully meeting the psychosocial needs of individuals after a stroke. Additionally, the study’s findings suggested that even therapists trained with the 2018 ACOTE standards continue to lack the knowledge, comfort, and/or skill to fully address the psychosocial needs of their patients, specifically stroke survivors. Thus, these findings may suggest that occupational therapy educational programs may need to further address this topic in their academic programs, and, perhaps, if further education and training regarding this topic was mandated for practicing therapists, this might facilitate the ability of occupational therapists to better address the psychosocial needs of stroke survivors. Future research investigating this topic would be beneficial to support the current evidence as well as provide additional information related to this topic.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Stroke facts. https:// www.cdc.gov/stroke/facts.htm. Accessed April 11, 2023. View

Simpson, E. K., Ramirez, N. M., Branstetter, B., Reed, A., Lines, E., (2018). Occupational therapy practitioners' perspectives of mental health practices with clients in stroke rehabilitation. OTJR (Thorofare N J). 38(3):181-189. [PMID: 29495909]. View

Hackett, M. L., Köhler, S., O'Brien, J. T., Mead, G. E., (2014). Neuropsychiatric outcomes of stroke. Lancet Neurol. 13(5):525 534. [PMID: 24685278]. View

Lin, F. H., Yih, D. N., Shih, F. M., Chu, C. M., (2019). Effect of social support and health education on depression scale scores of chronic stroke patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 98(44): e17667. [PMID: 31689780]. View

Dulay, M. F., Criswell, A., Hodics, T. M., (2023). Biological, psychiatric, psychosocial, and cognitive factors of poststroke depression. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 20(7):5328. [PMID: 37047944]. View

Wenzel, R. A., Zgoda, E. A., St. Clair, M. C., Knecht-Sabres, L. J., (2021). A qualitative study investigating stroke survivors’ perceptions of their psychosocial needs being met during rehabilitation. Open J Occup Ther. 9(2):1-16. View

Chohan, S. A., Venkatesh, P. K., (2019). How CH. Long-term complications of stroke and secondary prevention: an overview for primary care physicians. Singapore Med J. 60(12):616-620. [PMID: 31889205]. View

Northcott, S., Moss, B., Harrison, K., Hilari, K., (2016). A systematic review of the impact of stroke on social support and social networks: associated factors and patterns of change. Clin Rehabil. 30(8):811-831. [PMID: 26330297]. View

Busch, M. A., Coshall, C., Heuschmann, P. U., McKevitt, C., Wolfe, C. D., (2009). Sociodemographic differences in return to work after stroke: the South London Stroke Register (SLSR). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 80(8):888-893. [PMID: 19276102]. View

O'Sullivan, C., Chard, G., (2010). An exploration of participation in leisure activities post-stroke. Aust Occup Ther J. 57(3):159 166. [PMID: 20854584]. View

Jaber, A. F., Sabata, D., Radel, J. D., (2018). Self-perceived occupational performance of community-dwelling adults living with stroke. Can J Occup Ther. 85(5):378-385. [PMID: 30866681]. View

Reeves, M. J., Thetford, C., McMahon, N., Forshaw, D., Brown, C., Joshi, M., Watkins, C., (2022). Life and Leisure Activities following Stroke or Transient Ischaemic Attack (TIA): An Observational, Multi-Centre, 6-Month Follow-Up Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 9(21):13848. [PMID: 36360725]. View

Duxbury, S., Depaul, V., Alderson, M., Moreland, J., Wilkins, S., (2012). Individuals with stroke reporting unmet need for occupational therapy following discharge from hospital. Occup Ther Health Care. 26(1):16-32. [PMID: 23899105]. View

Seixas, A. A., Chung, D. P., Richards, S. L., et al. (2019). The impact of short and long sleep duration on instrumental activities of daily living among stroke survivors. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 15:177-182. [PMID: 30655670]. View

Shaik, M. A., Choo, P. Y., Tan-Ho, G., Lee, J. C., Ho, A. H.Y., (2024). Recovery needs and psychosocial rehabilitation trajectory of stroke survivors (PReTS): A qualitative systematic review of systematic reviews. Clin Rehabil. 38(2):263-284 [PMID: 37933440]. View

Stott, H., Cramp, M., McClean, S., Turton, A., (2021). 'Somebody stuck me in a bag of sand': Lived experiences of the altered and uncomfortable body after stroke. Clin Rehabil. 35(9):1348-1359. [PMID: 33706575]. View

Hodson, T., Gustafsson, L., Cornwell, P., (2020). The lived experience of supporting people with mild stroke. Scand J Occup Ther. 27(3):184-193. [PMID: 31264497]. View

Wijekoon, S., Wilson, W., Gowan, N., et al. (2020). Experiences of Occupational Performance in Survivors of Stroke Attending Peer Support Groups. Can J Occup Ther. 87(3):173-181. [PMID: 32115988]. View

Zawawi, N. S. M., Aziz, N. A., Fisher, R., Ahmad, K., Walker, M. F., (2020). The Unmet Needs of Stroke Survivors and Stroke Caregivers: A Systematic Narrative Review. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 29(8):104875. [PMID: 32689648]. View

Pringle, J., Drummond, J. S., McLafferty, E., (2013). Revisioning, reconnecting and revisiting: the psychosocial transition of returning home from hospital following a stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 35(23):1991-1999. [PMID: 23614358]. View

Wimpenny, K., Savin-Baden, M., Cook, C., (2014). A qualitative research synthesis examining the effectiveness of interventions used by occupational therapists in mental health. Br J Occup Ther. 77(6):276-288. View

Madhoun, H. Y., Tan, B., Feng, Y., Zhou, Y., Zhou, C., Yu, L., (2020). Task-based mirror therapy enhances the upper limb motor function in subacute stroke patients: a randomized control trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 56(3):265-271. [PMID: 32214062].View

2018 Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (ACOTE®) standards and Interpretive Guide (effective July 31, 2020). Am J Occup Ther. 72(Suppl 2). View

2011 Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (ACOTE®) standards. Am J Occup Ther. 2012; 66(Suppl 6). View

Jamil, A., Csendes, D., Gutlapalli, S. D., et al. (2022). Poststroke Depression, An Underrated Clinical Dilemma: 2022. Cureus. 14(12):e32948. [PMID: 36712776]. View

Wilson, K. A., Dirette, D. P., (2022). Clarifying mixed methodology in occupational therapy research. Open J Occup Ther. 10(2), 1-3. View

Creswell, J. W., Creswell, D., (2018). Research Design. 5th ed., SAGE Publications. View

Knecht-Sabres, L. J., (2010). The Use of Experiential Learning in an Occupational Therapy Program: Can it Foster Skills for Clinical Practice?. Occup Ther Health Care. 24(4):320-334. [PMID: 23898958]. View

Knecht-Sabres, L. J., (2013). Experiential Learning in Occupational Therapy: Can It Enhance Readiness for Clinical Practice? J Exp Educ. 36(1), 22-36. View