Journal of Rehabilitation Practices and Research Volume 6 (2025), Article ID: JRPR-189

https://doi.org/10.33790/jrpr1100189Research Article

Perceived Sensory Challenges in Car Passengers: Implications for Occupational Performance, Occupational Therapy Interventions, and Mobility Equity

Sara J Stephenson OTD, OTR/L, BCPR1*, Paige Morales OTS1, Avery Villani OTS1, Jodi Lindstrom OT/L, ATP2

1Department of Occupational Therapy, Northern Arizona University, Phoenix, Arizona, United States.

2Ashley Clyde, LLC, Phoenix, Arizona, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Sara J Stephenson OTD, OTR/L, BCPR, Associate Clinical Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy, Northern Arizona University, Phoenix, Arizona, United States.

Received date: 22nd September, 2025

Accepted date: 05th November, 2025

Published date: 07th November, 2025

Citation: Stephenson, S. J., Morales, P., Villani, A., & Lindstrom, J., (2025). Perceived Sensory Challenges in Car Passengers: Implications for Occupational Performance, Occupational Therapy Interventions, and Mobility Equity. J Rehab Pract Res, 6(2):190.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: Car travel as a passenger can cause sensory and physiological discomfort, yet its impact on daily function remains understudied. Passengers report motion-related discomfort such as fatigue or nausea. This survey examines the frequency, location, duration, and functional impact of these symptoms in adult passengers.

Aims: This study explores the types, locations, and functional effects of symptoms experienced by car passengers, emphasizing implications for community mobility.

Methods: A cross-sectional study with 45 adults using a self administered 26-question online survey to assess symptom frequency, location, duration, and impact on activities of daily living through descriptive statistics and qualitative analysis.

Results: Forty-five car passengers completed the survey; 35.5% reported no symptoms, while common symptoms included fatigue (24.4%), irritability (20%), and eye strain (13.3%), mainly affecting the eyes (28.8%), back (26.7%), and head (20%), with durations of 18–35 minutes and moderate impact on social and leisure activities.

Conclusions: Passenger discomfort varies widely, with implications for rehabilitation interventions. Implications: Findings inform strategies to enhance passenger comfort and mobility equity.

Keywords: Passenger Experience, Motion Sickness, Sensory Conflict, Community Mobility, Transportation Health

Practitioner Summary

Sensory and physiological discomfort in car passengers may limit participation in daily occupations and community mobility. This study identifies common challenges and provides insights for occupational therapy practice, offering strategies to improve comfort, safety, and accessibility during transportation.

Introduction

The relationship between the sensory system of a passenger and the car is complex and involves many different components. Car travel as a passenger involves unique sensory and physiological challenges, distinct from driving, yet remains under-researched [1]. Car travel is a common yet often overlooked activity that can significantly impact occupational performance, particularly for individuals receiving outpatient or home-based rehabilitation services where travel comfort and tolerance directly influence participation and consistency in therapy. Passengers lack control over the vehicle's movement, making it more difficult to anticipate changes in speed or direction and limiting their ability to make timely postural adjustments [2]. Subsequently, these unanticipated sensory and positional changes can lead to motion-related discomfort such as fatigue, dysregulation, or nausea [2,3]. Such symptoms may affect passengers’ readiness for daily activities, particularly for those reliant on car travel for community access [4,5]. Transportation is a key Social Determinant of Health, influencing participation, access, and well-being [6]. Over 6 million people stop driving annually, making clients reliant on being passengers [7]. For individuals who no longer drive, such as those with mobility barriers, passenger travel can be physically and emotionally demanding [8].

According to sensory conflict theory, motion sickness arises when mismatched sensory information from the visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive systems disrupts spatial orientation, leading to symptoms like nausea and fatigue [9,10]. Vehicle vibrations, sudden movements, and prolonged sitting further contribute to discomfort, affecting the vestibular and musculoskeletal systems [11]. Despite these physical challenges, factors like vehicle type, road conditions, and individual health also shape the subjective passenger experience [12]. However, sensory conflict theory represents only one explanation, as other research highlights the role of discrepancies between expected and actual sensory signals, further emphasizing the complexity of motion sickness mechanisms [13]. Existing research on the physiological impact of car travel has primarily focused on isolated body systems, examining the effects of motion, seated posture, and ride duration.

The quality of a client's transportation experience may influence not only their ability to access services but also their readiness to fully participate in therapy. AOTA’s Occupational Therapy Practice Framework, 4th Edition (OTPF–4) identifies transportation as a key component of both the contextual environment and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) [14]. Any mismatches between visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive inputs, as well as disruptions to spatial orientation, may contribute to symptoms such as dizziness, nausea, and fatigue [10]. Prolonged periods of sitting may cause stiffness and discomfort in muscles, particularly in the lower back and legs [11]. Additionally, sudden acceleration, deceleration, and directional changes may contribute to sensory overload, which can trigger motion-related symptoms. The posture maintained while seated can also affect body alignment, potentially leading to tension and strain in the neck and shoulders. This study addresses gaps in understanding how these systems interact and impact functional outcomes, informing transportation and health strategies [1].

Methodology

Participants

Eligible participants were adults aged 18 years or older who were proficient in English and had experience riding as a passenger in a vehicle. Individuals were excluded if they were under 18 years old, not proficient in English, or had no prior experience as a car passenger.

Recruitment

Respondents were recruited between March 1, 2024, to April 2, 2025, through a variety of strategies, including social media, email, flyers, participant referral, and word of mouth. Recruitment materials included a description of the study, an estimated time commitment of 20 minutes, potential risks and benefits, and a link to the online survey hosted on Qualtrics. Materials outlined the study’s purpose and provided a Qualtrics survey link, with electronic informed consent obtained.

Ethical Considerations

This study was reviewed and approved by the [REDACTED] Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee (Approval No. 2115279-2). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Survey Instrument

The Qualtrics survey, which included both structured and open ended questions developed by the research team and pilot-tested for clarity. Demographic questions included age, frequency of car passenger trips per week, and symptom history. Symptom-related questions were presented using a drop down menu with options (nausea, dizziness, fatigue, pain, and other). Participants could specify additional symptoms using an open-text field. Respondents reported the location of symptoms using a predefined list (e.g., head, neck, shoulders, back, legs) and could add locations via an open- text option. A follow-up question allowed participants to estimate the duration of symptoms (in minutes) using a free-text response. A Likert-scale section (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) assessed symptom impacts on ADLs and instrumental ADLs (IADLs), such as self-care, work, and social participation.

Data Management and Analysis

Responses were stored securely on Qualtrics’ encrypted platform, which is encrypted end to end. After collection, data were de identified and exported to Microsoft Excel for analysis. Descriptive statistics (means, frequencies, percentages) summarized demographic and symptom data. Symptom locations were grouped into anatomical regions (e.g., head, neck, back). Likert-scale responses were collapsed into Agree, Neutral, and Disagree categories. Open-ended responses were reviewed qualitatively to identify additional themes that were not captured by the closed-ended questions. Qualitative responses were thematically analyzed to identify emergent patterns.

Results

Participant Characteristics

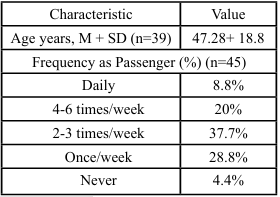

A total of 45 participants completed the survey. Thirty-nine provided age information, with reported ages ranging from 21-83 years (M = 47.3, SD = 18.8). Participant demographics for age and frequency of riding in a car as a passenger are presented in Table 1. All participants reported having experience riding in a car as a passenger. Most participants completed the survey in full (n=39), with minor instances of missing data across individual questions.

Table 1. Alt Text: Table showing participant demographics. Average age was 47 years (SD = 18.8). Most participants rode as a car passenger 2–3 times per week (37.7%) or once per week (28.8%), with smaller groups riding 4–6 times per week (20%), daily (8.8%), or never (4.4%).

Perceived Symptom Information

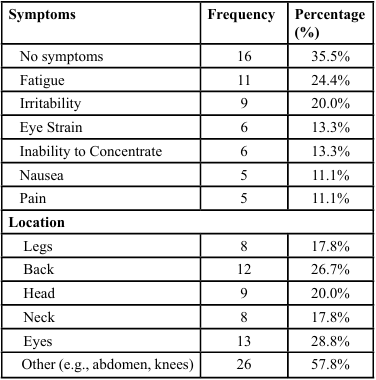

Symptom Frequency and Type

Participants reported a range of symptoms experienced while riding in a car as a passenger. The most frequently reported symptoms included dizziness, fatigue, headaches, nausea, and eye strain. Less common symptoms included irritability, numbness, rapid heart rate, and tingling. A small number of participants (n=6) used the free-text option to report symptoms not listed in the drop-down menu, such as stomach discomfort, visual disturbances, and motion sensitivity. Symptom frequency and types are provided in Table 2.

Symptom Location

Participants identified various body locations affected by symptoms. Locations were grouped into anatomical regions to facilitate analysis. The most commonly reported regions included the head (including eyes and ears), neck, back, and lower extremities. Some reported radiating pain or multiple affected areas. See Table 2 for a summary of symptom locations by region.

Table 2 Alt Text: Table summarizes reported symptoms and locations. Common symptoms included fatigue (24.4%), irritability (20%), and eye strain (13.3%), while 35.5% reported no symptoms. Locations most often affected were eyes (28.8%), back (26.7%), and other areas such as abdomen or knees (57.8%).

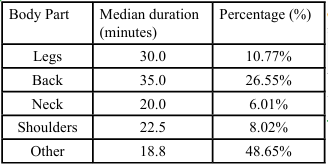

Symptom Duration

Symptom duration varied, ranging from minutes to over 120 minutes. Duration responses were open-ended, and many included context-specific qualifiers such as “depends on the length of the car ride” or “lingers for several hours if the trip is long.” Participants noted duration depended on trip length. Because of the variability and narrative format, a descriptive summary of symptom duration is presented in Table 3.

Table 3 Alt Text: Table showing median symptom duration by body location. Symptoms lasted a median of 30 minutes in the legs (10.77%), 35 minutes in the back (26.55%0, 20 minutes in the neck (6.01%), 22.5 minutes in the shoulders (8.02%), and 18.8 minutes in other areas (48.65%).

Impact on Daily Function

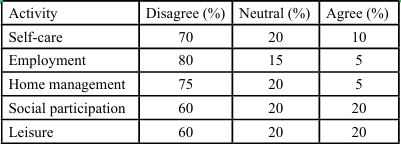

Participants (35%) reported no significant impact on ADLs or participation. However, a majority of participants agreed that symptoms interfered with at least one area function. Social participation, family involvement, and leisure activities were most frequently affected, followed by work duties and self-care. Responses to the Likert-scale items were collapsed into three categories (Agree, Neutral, Disagree) for analysis. These results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4 Alt Text: Table showing percentage of impact on daily functions. Self care has 10% agree, 20% neutral, and 10% disagree. Employment has 5% agree, 15% neutral, and 80% disagree. Home management has 5% agree, 20% neutral, and 75% disagree. Social participation has 20% agree, 20% neutral, and 60% disagree. Leisure has 20% agree, 20% neutral, and 60% disagree.

Discussion

This study reveals diverse sensory and functional impacts of car passenger travel. Common symptoms (nausea, dizziness, fatigue, and headaches) suggest a relationship between passenger travel and vestibular or sensory discomfort [9,15]. Symptom locations were primarily concentrated in the head, neck, and back, potentially reflecting postural strain, visual or vestibular disturbances, motion sensitivity, or musculoskeletal sensitivity during vehicle motion. Importantly, the findings highlight the subjective nature of the passenger experience, as some participants described discomfort and functional limitations, while others reported no symptoms or even a sense of relaxation during car travel. The variability in experiences, with some finding travel relaxing, underscores individual differences influenced by health, vehicle type, or road conditions [2,3].

In the free-response questions, participants frequently described neck stiffness and tension as common passenger experiences, often worsening during longer trips. This discomfort was attributed to sustained postures, limited movement, or poor seat ergonomics. Several participants also mentioned sensory symptoms such as light sensitivity, eye strain, inner ear discomfort, and nausea. Overall, four main themes emerged: musculoskeletal tension, sensory discomfort, emotional fatigue, and duration-dependent effects. Participants reported stiffness in the neck, back, and hips, as well as sensory issues like light sensitivity, eye strain, and nausea related to vestibular or visual factors. Some also noted irritability and difficulty concentrating during longer rides, reflecting cognitive and emotional influences. These findings highlight the complex interplay of physical, sensory, and psychological factors shaping the passenger experience.

Although passenger comfort has been examined in fields such as human factors, transportation safety, and vestibular science, it remains largely underexplored within occupational therapy literature [2,4,5]. This study contributes to transportation research by linking passenger discomfort to functional outcomes, relevant to human factors and public health [1]. Findings suggest vehicle design (e.g., ergonomic seats, motion-dampening systems) and road conditions could mitigate symptoms, enhancing mobility equity.

Limitations

The small, self-selected sample limits the generalizability of findings, as such samples may not represent the broader population of interest. All responses were self-reported, which may introduce recall or response bias. Self-reported data may introduce bias, and the cross-sectional design restricts insights into symptom progression. Dropdown menus may have constrained responses.

Implications for OT practice

This study identifies passenger car travel as a potential barrier— or, in some cases, a support—to occupational engagement. For some individuals, symptoms experienced while traveling may deter participation in community, social, or family activities. For others, the car ride itself may serve as a time for rest or transition. Occupational therapists should explore these varied experiences in client interviews and assessments, particularly when transportation challenges are evident or indirectly influencing participation.

Intervention approaches might include sensory strategies, fatigue management, ergonomic recommendations, or caregiver education related to ride conditions (e.g., posture, noise, motion). Therapists may also play a role in problem-solving alternatives to car travel or advocating for transportation accommodations in the community. For clients receiving outpatient or school-based occupational therapy services, transportation to and from sessions should be considered as a contextual factor influencing occupational performance. If clients arrive dysregulated, fatigued, or overstimulated from the trip itself, this may impact their participation and responsiveness to therapy. Therapists should routinely ask about travel conditions and consider interventions that support pre-session readiness. Table 5 provides examples of considerations and intervention approaches.

Table 5 Alt Text: Table outlining occupational therapy interventions across travel phases. Pre-trip: positioning and ergonomics to reduce postural strain with lumbar supports, stretching and mobility to prepare joints with exercise handouts, anxiety management strategies to lower stress using breathing apps and visualization. In-transit: motion sickness mitigation with peppermint oil, acupressure bands, and forward-facing seating, in-car micro-breaks to reduce tension through stop-and-stretch plans. Post-trip: recovery stretching and sensory regulation to ease symptoms using foam rollers, doorway stretches, and calming kits, strategies for reorientation with headphones or weighted lap pads. Modifications include sunglasses for visual comfort, calming music for emotional regulation, and memory foam supports for pressure relief.

Conclusion

Passenger experiences during car travel vary widely, ranging from discomfort and activity avoidance to relaxation and ease. For individuals whose symptoms negatively impact function, these experiences may limit access to meaningful activities across domains. Occupational therapists are well positioned to recognize and address the functional implications of transportation challenges. Future research should examine these issues longitudinally and in larger, more diverse populations to better inform clinical practice and public health strategies.

Disclosures:

The authors have no personal, financial, or institutional interest in any of the materials, or devices described in this manuscript.

Financial Support:

None

Author Contributions Statement

Jodi Lindstrom, OT/L, ATP, and Sara Stephenson, OTD, OTR/L, contributed to the conceptualization of the study and provided supervision throughout the project. Methodology was developed collaboratively by Avery Villani, OTS, Paige Morales, OTS, and Sara Stephenson, OTD, OTR/L. Data collection, curation, and analysis were performed by Avery Villani, OTS, Paige Morales, OTS, and Sara Stephenson, OTD, OTR/L. Avery Villani and Paige Morales prepared the original draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to review and editing, with Sara Stephenson, OTD, OTR/L, providing additional critical revisions. All authors reviewed the manuscript critically for accuracy and clarity, offered feedback to strengthen the analysis and presentation, and approved the final version for publication. Each author agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work and affirms that they meet the criteria for authorship as outlined by the ICMJE guidelines.

References

Ittner, S., Mühlbacher, D., & Weisswange, T. H. (2020). The discomfort of riding shotgun – why many people don’t like to be co-driver. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 584309. View

Song, Y., Yoon, B., Park, J., Bae, J., Seu, D., Yang, J., Kim, S., & Yun, M. H. (2023). A Systematic Literature Review for Measure, Estimation, and Mitigation of Motion Sickness in Vehicle Environment. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 67(1), 1400-1402. View

Chang, C. H., Stoffregen, T. A., Cheng, K. B., Lei, M. K., & Li, C. C. (2021). Effects of physical driving experience on body movement and motion sickness among passengers in a virtual vehicle. Experimental Brain Research, 239(2), 491–500. View

Solomon, J., et al. (2020). Impact of transportation interventions on health care outcomes: A systematic review. Medical Care, 58(6), 551–558. View

Kim, K., Norton, S. A., & Ritchie, C. S. (2020). Systematic review of interventions to minimize transportation barriers among people with chronic diseases. American Journal of Public Health, 110(2), e1–e11.

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2023). In the community: Navigating public transportation. OT Practice. View

Chihuri,S.,Mielenz, T. J., DiMaggio, C.J., Betz, M. E., DiGuiseppi, C., Jones, V.C., & Li, G., (2016). Driving Cessation and Health Outcomes in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 64(2):332-41. View

O’Neill, D., Walshe, E., Romer, D., & Winston, F. (2019). Transportation equity, health, and aging: A novel approach to healthy longevity with benefits across the life span. NAM Perspectives. View

Irmak, T., Pool, D. M., & Happee, R. (2023). Validating models of sensory conflict and perception for motion sickness prediction. Biological Cybernetics, 117(3), 185. View

Bertolini, G., & Straumann, D. (2016). Moving in a Moving World: A Review on Vestibular Motion Sickness. Frontiers in Neurology, 7, 175198. View

Okunribido, O. O., Shimbles, S. J., Magnusson, M., & Pope, M. (2007). City bus driving and low back pain: A study of the exposures to posture demands, manual materials handling and whole-body vibration. Applied Ergonomics, 38(1), 29-38. View

Koohestani, A., Nahavandi, D., Asadi, H., Kebria, P. M., Khosravi, A., Alizadehsani, R., & Nahavandi, S. (2019). A knowledge discovery in motion sickness: A comprehensive literature review. IEEE Access, 7, 85755–85770. View

Nooij, S.., Bockisch, C. J., Bülthoff, H. H., & Straumann, D. (2021). Beyond sensory conflict: The role of beliefs and perception in motion sickness. PLoS ONE, 16(1), e0245295. View

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl. 2), 7412410010p1–p87. View

Lackner, J. R. (2014). Motion sickness: More than nausea and vomiting. Experimental Brain Research, 232(8), 2493–2510. View

van Deursen, L. L., & Snijders, C. J. (1993). Lumbar flexion- relaxation phenomenon and its clinical application. Spine, 18(5), 638–643.

Varvogli, L., & Darviri, C. (2011). Stress management techniques: Evidence-based procedures that reduce stress and promote health. Health Science Journal, 5(2), 74–89. View

Lane, N. E., & Avorn, J. (1993). Acupressure in motion sickness: A pilot study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 153(7), 849–852.

Dicianno, B. E., et al. (2018). Stretching and mobility preparation in persons with disabilities. Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports, 6, 287–295.