Journal of Rehabilitation Practices and Research Volume 6 (2025), Article ID: JRPR-190

https://doi.org/10.33790/jrpr1100190Commentary Article

Facilitating Physical Activity Through the Stages of Care for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD): Practical Guidance for Healthcare Professionals and Caregivers

Jonathan H. Anning1*, PhD, CSCS*D, FNSCA, Jason Edinger2, DO, and Casey Matthews3, DPT

1Associate Professor, Department of Exercise Science, Slippery Rock University, Slippery Rock, PA 16057, United States.

2Assistant Professor, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA 15261, United States.

3UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15224, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Jonathan H. Anning, PhD, CSCS*D, FNSCA, Associate Professor, Department of Exercise Science, Slippery Rock University, Slippery Rock, PA 16057, United States.

Received date: 16th September, 2025

Accepted date: 07th November, 2025

Published date: 10th November, 2025

Citation: Anning, J. H., Edinger, J., & Matthews, C., (2025). Facilitating Physical Activity Through the Stages of Care for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD): Practical Guidance for Healthcare Professionals and Caregivers. J Rehab Pract Res, 6(2):190.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Physical activity plays a vital role in supporting functional ability, psychosocial well-being, and quality of life for individuals with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). While advances in pharmacologic and genetic treatments continue to evolve, these medical therapies alone cannot preserve function or participation. This article provides practical, stage-based guidance for healthcare professionals and caregivers to facilitate safe, meaningful physical activity across the DMD lifespan. Recommendations emphasize maintaining joint range of motion, cardiorespiratory capacity, and community engagement through adaptable and enjoyable activity participation. Table 1 summarizes progressive goals, therapeutic activities, and supportive interventions to assist in aligning care strategies with disease progression.

Keywords: Rehabilitation, Exercise Prescription, Motor Function, Disease Progression, Quality of Life, Multidisciplinary Approach, Patient-Centered, Assistive Technology

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a progressive, X-linked disorder characterized by the absence of the dystrophin protein, which leads to chronic and irreversible muscle weakness [1-4]. Although a variety of FDA-approved therapies now exist for DMD, no definitive medical cure is available. Recent pharmacologic and gene-based advances, including corticosteroids, cardiac interventions, and micro-dystrophin therapy, have increased life expectancy, but offer only limited gains in quality of life [5-8]. This is primarily because these medical treatments do not fully address the progressive weakening of skeletal, cardiac, and respiratory muscles that lead to cardiopulmonary complications [5]. This highlights the critical need to incorporate physical activity into the medical treatment plan to better manage disease progression.

Despite increased life expectancy for those born in recent decades [5,9], many DMD individuals are not diagnosed until ages four to five, often following a delay of up to two years after symptoms first appear [1,2]. This delay, along with the progressive nature of the disease, contributes to significant challenges related to deconditioning, contracture formation, and cardiopulmonary decline, which restrict participation in daily and recreational activities. The genetic landscape is also varied, with 80% of mutations being large rearrangements (deletions at 69% and duplications at 11%), and the remaining 20% being small mutations, including insertions, deletions, and splice site mutations [10].

Given these persistent challenges, a comprehensive, stage appropriate approach to physical activity is crucial. It serves to optimize health, function, and well-being, while complementing the constantly evolving medical care. Accordingly, this article focuses on optimizing physical activity, broadly defined as any movement that enhances health, function, or well-being, across each stage of DMD care.

General Physical Activity Considerations

Anning [11] researched physical activity as a treatment for DMD, highlighting its benefits for maintaining muscle function, preventing contractures, and complimenting other treatment strategies. Building on this foundation, physical activity in DMD should be viewed as an adaptive continuum rather than a rigid, one-size-fits-all prescription. Activities must align with the individual’s musculoskeletal health, functional capacity, and fatigue threshold.

A multidisciplinary approach is crucial for optimizing safety and effectiveness, requiring coordination among DMD specialists, including physicians, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and caregivers to tailor physical activities appropriately across disease stages. Regular musculoskeletal range of motion (ROM) activities that stretch the upper and lower extremities help preserve flexibility and prevent contractures [12]. Furthermore, engaging in enjoyable, low-intensity movement promotes circulation, reduces stiffness, supports respiratory and cardiac functional capacity, and enhances social connection and emotional well-being [11,13]. To prevent accelerated muscle damage, it is essential to avoid fatigue and overexertion, since excessive loading, especially eccentric muscle contractions, is a major risk factor for muscle breakdown [14]. Therefore, clinically guided physical activity for the DMD population should prioritize fun, low-intensity, comfortable, and sustainable movements that are smooth and controlled to promote blood circulation and flexibility while minimizing strain [11-14].

Cardiac and respiratory complications are a leading cause of mortality in DMD, and overexertion can accelerate this decline. Proactive monitoring for early warning signs of overexertion (e.g., fatigue persisting beyond rest periods, muscle cramping or pain, dark-colored urine, difficulty sleeping) is essential [15-18]. If any indication of cardiorespiratory distress occurs, such as excessive sweating, chest pain, or shortness of breath, activity should be discontinued and evaluated by a clinician [17,18].

Stage-Based DMD Physical Activity Overview

To guide healthcare professionals and caregivers in selecting appropriate activities across the progression of DMD, it is helpful to view physical activity recommendations in a stage-based framework [1,2]. Because disease progression varies considerably due to underlying genetic mutations and therapeutic interventions, a universal trajectory is difficult to define. However, the general pattern involves progressive weakness that begins proximally (hips and shoulders) and advances distally, eventually affecting respiratory and cardiac muscles. This variability in onset and rate of decline underscores the need for an adaptable, stage-based framework to guide clinical and physical activity recommendations. Each stage reflects the evolving physical capabilities and medical considerations of the individual, highlighting how goals shift from promoting development and preserving mobility to maintaining cardiorespiratory health, community access, and comfort.

These stages are intended to guide safe participation in physical activity throughout the progression of DMD function. Each stage builds on the previous one unless specific weaknesses prevent an activity. While every stage has its own focus, no priority from an earlier stage should be abandoned. Daily lower and upper extremity stretching to prevent contractures, avoidance of eccentric loading, and careful fatigue management always remain essential. Activity selection should progress with the individual, but the underlying principles of preserving function, dignity, comfort, and enjoyment should remain constant. Importantly, engagement in meaningful, community-based participation should persist from diagnosis through late-stage care.

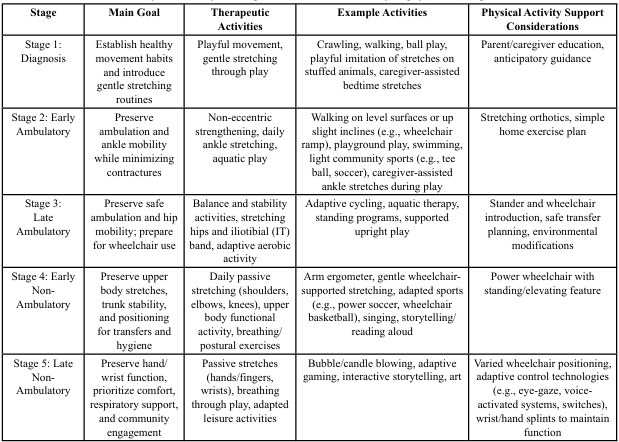

Table 1 summarizes the primary goals, suggested therapeutic activities and examples, and physical activity-supportive interventions for each stage of care, providing a concise reference for aligning physical activity strategies with the progression of DMD. The sections that follow expand on each stage summarized in Table 1, offering more detailed guidance on how these recommendations can be applied in daily routines by healthcare professionals and caregivers.

Stage 1: Diagnosis and Early Phase (Presymptomatic to Early Weakness)

At this stage children with DMD are often developing motor skills and participating in typical childhood play. The primary goal is to maintain functional mobility and encourage normal physical development. Gross motor milestones at this stage include sitting independently, crawling, walking (around 18 months on average), running, climbing stairs, and jumping. While children with DMD may achieve these skills, subtle early signs like frequent falls, a waddling gait, or difficulty rising from the floor (Gower maneuver) may become apparent between 2-3 years of age [19]. Despite these early clues, obvious signs are often minimal, so activities should feel similar to peers. Physical activity should focus on natural play, gentle walking, and stretching of major muscle groups without causing fatigue or discomfort [18]. Following a diagnosis, medical management typically begins with corticosteroids while initiating cardiorespiratory monitoring.

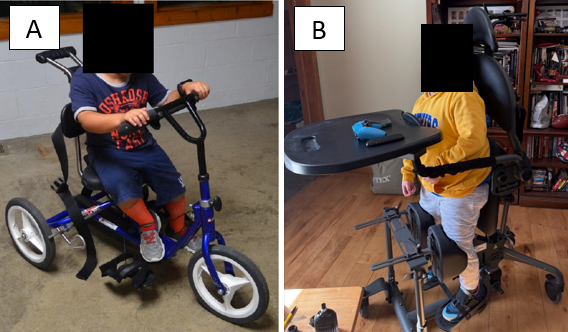

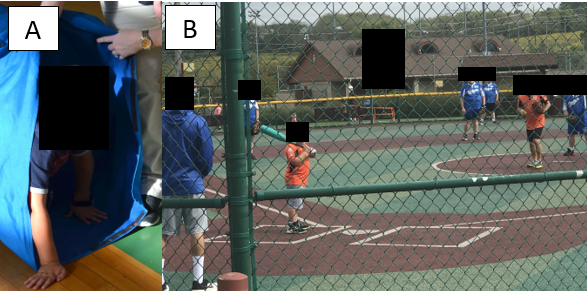

Practical activities (Figure 1) include age-appropriate play, such as crawling, and facilitated or assisted ball games. Caregivers should avoid encouraging high-resistance activities and be cautious about fatigue signs, ensuring physical activity remains enjoyable and non exhaustive [11,20]. Gentle bedtime stretching for the calves and hamstrings can help maintain lower extremity flexibility. Encourage caregivers to integrate flexibility through playful stretching routines, such as “stretching with stuffed animals,” to increase compliance and enjoyment.

Figure 1. Stage 1 DMD boy (A) crawling through soft tunnel and (B) playing baseball in a community-based adapted sports league.

Stage 2: Early Ambulatory Phase

This stage is characterized by increasing motor delays, frequent falls, and rising to stand using a Gowers’ maneuver. The focus remains on preserving ambulation and minimizing contractures. Low-impact aerobic exercises like swimming and gentle walking promote endurance and function without placing excessive stress on muscles [17]. Orthotic devices may be introduced to support flexibility and alignment, such as nighttime stretching Ankle-Foot Orthotics (AFOs). These devices help preserve mobility and comfort during activity. Routine monitoring for scoliosis, as well as early cardiac and pulmonary evaluations, complements these strategies by ensuring activity remains safe and sustainable.

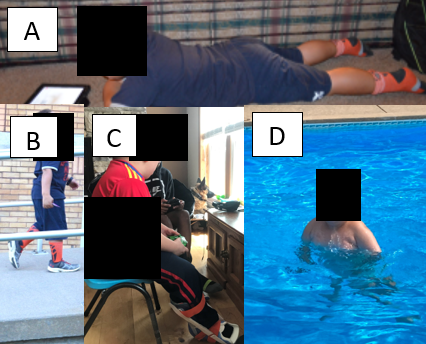

Practical examples (Figure 2) include aquatic play and level or slight incline walking. While the emphasis may shift to gait efficiency and safety during this stage, lower extremity stretching from Stage 1 should continue daily [17]. Avoidance of jumping, running downhill, or other eccentric-heavy movements is critical to reduce injury risk [18]. Encouraging fun, low-impact activities will help sustain engagement without exacerbating weakness.

Figure 2. Stage 2 DMD boy (A) reading aloud as a breathing exercise while lying prone to stretch hip flexors, (B) walking up wheelchair ramp, (C) playing a video game while stretching calves with a stretching nighttime splint, and (D) moving in a pool.

Stage 3: Late Ambulatory Phase

With increasing difficulty walking, the focus shifts to maximizing independence through modified activities. Adaptive cycling and aquatic therapy offer excellent cardiovascular and musculoskeletal benefits while minimizing joint stress [11]. Activities should be shorter in duration with frequent rest intervals, as fatigue management becomes central to care [16]. Medical care intensifies during this phase, with more frequent cardiorespiratory evaluations and scoliosis checks. The psychological impact of declining independence should also be supported through social activities in the community that reinforce self-worth.

Practical examples (Figure 3) include adaptive bikes to enable safe lower body movements without excessive stress, or water-based walking and floating exercises to reduce joint loading. Wheelchair use may be introduced to reduce fall risk, conserve energy, and prevent excessive fatigue. Supported standing devices should also be considered, even while limited ambulation is still possible, as they promote bone health, posture, digestion, and respiratory function [3]. Introducing a stander before full-time wheelchair use helps maintain upright positioning as part of daily routines. Above all, activities should emphasize enjoyment over achievement, allowing people with DMD to feel empowered and safe. Promoting independence remains a central goal.

Stage 4: Early Non-Ambulatory Phase

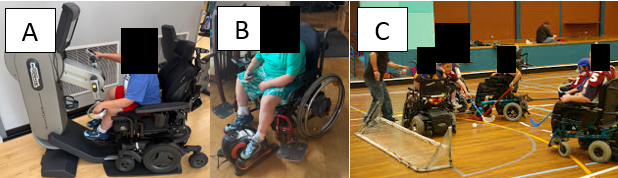

With full-time wheelchair use, upper body and trunk function become the primary emphasis, while lower extremity stretching remains essential for positioning, dressing, and hygiene [5]. Independence in daily activities such as eating and grooming contributes greatly to emotional well-being and should be supported through targeted interventions [3]. Respiratory health is reinforced with breathing exercises and postural adjustments, and daily passive ROM for both upper and lower limbs help prevent contractures [17].

Practical activities (Figure 4) include hand cycling while watching TV, reading aloud as a breathing exercise, and participation in adaptive sports such as power soccer or wheelchair basketball. These options provide both social engagement and enjoyable exercise opportunities. Non-invasive respiratory support devices (e.g., BiPAP) may also be implemented at this stage to reduce fatigue and enhance activity tolerance. A multidisciplinary approach remains vital, ensuring that quality of life and safe physical activity are sustained.

Figure 4. Stage 4 DMD boy (A) using arm ergometer and (B) electric elliptical trainer in wheelchair, and (C) competing in wheelchair hockey.

Stage 5: Late Non-Ambulatory Phase

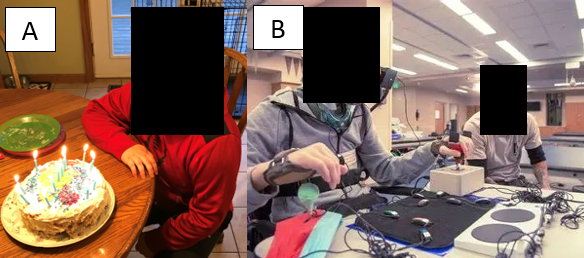

In the final stage, activities should prioritize comfort, respiratory support, and prevention of complications such as pressure injuries. Daily passive ROM for both upper and lower limbs remain essential, along with varied body positioning. Postural adjustments and breathing exercises are central, particularly in coordination with respiratory technologies like tracheostomy or ventilator support [5].

Assistive technologies play an increasingly critical role in this stage, not only for communication and environmental control, but also for sustaining participation in daily routines. To prevent wrist and hand contractures and preserve self-feeding and communication, arm/wrist splints may be used, often during rest or sleep. Adaptive switches and voice-activated control devices integrated with power wheelchairs help people with DMD maintain autonomy and engagement. Adaptive gaming systems, such as eye-gaze–controlled or switch-based platforms, provide opportunities for recreation, social interaction, and a sense of accomplishment. Together, these supportive devices promote dignity and quality of life even with significant physical limitations [21].

Practical strategies (Figure 5) include integrating gentle stretching into morning and bedtime routines, supporting deep breathing through talking or reading games, engaging in adaptive gaming, and ensuring varied positioning to prevent pressure injuries. Gentle social activities like interactive storytelling or adapted art further support psychological well-being. Across all activities, the focus remains on comfort, connection, and enjoyment.

Figure 5. Stage 5 DMD boy (A) blowing out candles after helping to make the cake, and (B) using adaptive gaming kit to play video games.

Conclusion

Physical activity across the DMD continuum must balance safety, independence, and enjoyment. By applying stage-based recommendations, healthcare professionals and caregivers can foster lifelong engagement in movements that preserve function, support respiratory health, and promote overall well-being. A consistent focus on stretching, posture, fatigue management, and community inclusion ensures individuals with DMD experience continued participation and dignity throughout every phase of care.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Birnkrant, D. J., Bushby, K., Bann, C. M., Alman, B. A., Apkon, S. D., Blackwell, A., Case, L. E., Cripe, L., Hadjiyannakis, S., Olson, A. K., Sheehan, D. W., Bolen, J., Weber, D. R., & Ward, L. M. (2018). Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: Diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. The Lancet Neurology, 17(3), 251–267. View

Birnkrant, D. J., Bushby, K., Bann, C. M., Alman, B. A., Apkon, S. D., Blackwell, A., Case, L. E., Cripe, L., Hadjiyannakis, S., Olson, A. K., Sheehan, D. W., Bolen, J., Weber, D. R., & Ward, L. M. (2018). Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: Respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. The Lancet Neurology, 17(4), 347–361. View

Bushby, K., et al. (2010). Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: Diagnosis, and pharmacological and psychosocial management. The Lancet Neurology, 9(1), 77–93. View

Bushby, K., Finkel, R., Birnkrant, D. J., Case, L. E., Clemens, P. R., Cripe, L., Kaul, A., Kinnett, K., McDonald, C., Pandya, S., Poysky, J., Shapiro, F., Tomezsko, J., & Constantin, C. (2010). Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: implementation of multidisciplinary care. The Lancet Neurology, 9(2), 177–189. View

Birnkrant, D.J., Bello, L., Butterfield, R.J., Carter, J.C., Cripe, L.H., Cripe, T.P., McKim, D.A., Nandi, D., & Pegoraro, E. (2022). Cardiorespiratory management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: emerging therapies, neuromuscular genetics, and new clinical challenges. The Lancet Neurology, 10(4), 403-420. View

Mah, J. K. (2025). Therapeutic options for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Hope or hype? Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders, 18, 17562864251346326. View

Shah, M. N. A., & Yokota, T. (2023). Cardiac therapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders, 16, 17562864231182934. View

D’Ambrosio, E. S., & Mendell, J. R. (2023). Evolving therapeutic options for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurotherapeutics, 20(6), 1669–1681. View

Davidson, Z. E., Vidmar, S., Griffiths, A., Howard, M. E., Berlowitz, D. J., Jones, E. F., Scully, Z., Treanor, D., Singh, B. Prior, D., Frost, M. G., Forbes, R., Billich, N., Adams, J., Carroll, K., Al Lawati, T., Bourne, H., Kornberg, A. J., Ryan, M. M., Woodcock, I. R., Yiu, E. M., & Cheung, M. M. H. (2025). Survival in Duchenne muscular dystrophy in Australia: a 50 year retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Regional Health: Western Pacific, 58, 101568. View

Gatto F, Benemei S, Piluso G, Bello L. (2024). The complex landscape of DMD mutations: moving towards personalized medicine. Frontiers in Genetics. 15, 1360224. View

Anning J.H. (2022). Potential Benefits of Using Exercise as a Treatment. Strategy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD). Professionalization of Exercise Physiology online. 25(4):1-16.

Mercuri, E., & Muntoni, F. (2013). Mechanisms and management of muscle contractures in DMD. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 55(9), 780–785.

D'Amico, A., Catteruccia, M., Baranello, G., Politano, L., Govoni, A., Previtali, S. C., Pane, M., D'Angelo, M. G., Bruno, C., Messina, S., Ricci, F., Pegoraro, E., Pini, A., Berardinelli, A., Gorni, K., Battini, R., Vita, G., Trucco, F., Scutifero, M., Petillo, R., D'Ambrosio, P., Ardissone, A., Pasanisi, B., Vita, G., Mongini, T., Moggio, M., Comi, G. P., Mercuri, E., and Bertini, E. (2017). Physical therapy and rehabilitation in DMD. Neuromuscular Disorders, 27(10), 893–898. View

Eagle, M., Baudouin, S. V., Chandler, C., Giddings, D. R., Bullock, R., & Bushby, K. (2007). Fatigue management in DMD. Physiotherapy Research International, 12(3), 175–188.

Anning, J.H., Feltman, M., Sweeney, D., Yuhas, M., & Bendixen, R. (2017). Pilot Study: Monitoring physical activity level and sleep pattern relationships among boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy using a fitness band. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31, S233-S234.

Bendixen, R., Kelleher, A., & Anning, J. (2018). Monitoring physical activity levels and sleep pattern relationships in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(4 Supplement 1). View

Lott, D. J., Taivassalo, T., Cooke, K. D., Park, H., Moslemi, Z., Batra, A., Forbes, S. C., Byrne, B. J., Walter, G. A., & Vandenborne, K. (2021). Safety, feasibility, and efficacy of strengthening exercise in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve, 63(3), 320-326. View

Muscular Dystrophy Association. (2009). Exercising with a Muscle Disease. Quest, 16(2), 24-94. View

Mercuri, E., Pane, M., Cicala, G., Brogna, C. and Ciafaloni, E. (2023). Detecting early signs in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: comprehensive review and diagnostic implications. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 11, 1276144. View

Jansen, M., De Jong, M., Coes, H. M., Eggermont, F., Van Alfen, N., & De Groot, I. J. (2012). The assisted 6-minute cycling test to assess endurance in children with a neuromuscular disorder. Muscle Nerve, 46, 520–530. View

Sakzewski, L., Ziviani, J., & Boyd, R. N. (2013). The relationship between pediatric assistive technology use and activity performance in children with physical disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 8(5), 408-417.