Journal of Rehabilitation Practices and Research Volume 6 (2025), Article ID: JRPR-191

https://doi.org/10.33790/jrpr1100191Research Article

Health Disparities in Pain: Leveraging Quantitative Sensory Testing and Health-Related Measures to Identify Risk Factors for Chronic Pain

Carla S. Enriquez, PT, PhD, DPT, MS, OCS1,2*, Musola Oniyide, PT, DPT2,3, Christine Tolerico, PT, MPT2, Nicole Rommer, PT, DPT, CLT-LANA2, Thomas Koc, PT, PhD, DPT, OCS, FAAOMPT1, John Lee, PT, PhD, DPT, OCS1, and Patrick Hilden, DrPH4,5

1Department of Physical Therapy, College of Health Professions and Human Services, Kean University, Union, New Jersey, United States of America.

2Physical Therapy Department, Comprehensive Outpatient Rehabilitation Center, Cooperman Barnabas Medical Center, Livingston, New Jersey, United States of America.

3Physical Therapy Department, Overlook Medical Center, Atlantic Health System Inc, Union, New Jersey, United States of America.

4Biostatistics Department, Cooperman Barnabas Medical Center, Livingston New Jersey, United States of America.

5Department of Biostatistics, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, New York, United States of America.

Corresponding Author Details: Carla S. Enriquez, PT, PhD, DPT, MS, OCS, Assistant Professor, Department of Physical Therapy, College of Health Professions and Human Services, Kean University, North Avenue Academic Building, 1000 Morris Avenue, Union, NJ 07083, United States of America.

Received date: 19th November, 2025

Accepted date: 26th December, 2025

Published date: 28th December, 2025

Citation: Enriquez, C. S., Oniyide, M., Tolerico, C., Rommer, N., Koc, T., Lee, J., & Hilden, P., (2025). Health Disparities in Pain: Leveraging Quantitative Sensory Testing and Health-Related Measures to Identify Risk Factors for Chronic Pain.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Introduction: Pain is a complex, multidimensional phenomenon affecting approximately 21% of adults and remains the leading cause of disability in the United States. Its evolving definition reflects diverse etiologies, yet pain is ubiquitous and imposes a substantial global health burden through increased health care costs and lost productivity.

Objective: To examine associations between health-related measures and individual pain processing mechanisms using Quantitative Sensory Testing (QST) in healthy adults. This study examined associations between health-related measures and individual pain processing mechanisms using Quantitative Sensory Testing (QST) in healthy adults.

Methods: A cohort study was conducted among adults 18–65 years old (n = 43). Health-related measures included the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), State-Trait Anxiety Index (STAI), and Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS). Neural pain processing outcomes were assessed using standardized QST procedures: mechanical Pressure Pain Threshold (PPT), Temporal Summation (TS), and Conditioned Pain Modulation (CPM).

Results: Univariate analyses revealed that men and individuals with BDI scores ≥11 exhibited greater PPT values (p < 0.001 and p = 0.049, respectively). Hispanic/Latino participants demonstrated higher PPT values (p = 0.056), with non-Hispanic/Latino participants showing predicted scores 3.3 lbs lower (95% CI: –6.1, –0.5; p = 0.024). PPT differences were significant across sex and depression levels but not anxiety. Multivariate modeling confirmed that men, Hispanic/Latino participants, and individuals with BDI scores ≥11 had higher PPT values (p < 0.001, p = 0.002, and p = 0.024, respectively). Participants with BDI scores ≥11 exhibited 3.8 lbs higher PPT values compared to those with scores ≤10 (95% CI: 1.2, 6.5; p = 0.004). Significant differences in TS were observed between low and high PCS groups (p = 0.042), indicating that pain catastrophizing behaviors are associated with heightened pain sensitization.

Conclusion: Health-related measures were associated with aberrations in pain processing mechanisms in healthy individuals, mirroring clinical features observed in chronic pain populations. Findings highlight the potential predictive utility of QST, an objective pain assessment tool widely used in research and clinical prognostication. Targeted prevention and intervention strategies including screening of asymptomatic but at-risk groups are critical for advancing public health and pain literacy. These efforts can inform communities, policymakers, organizational leaders, and public health advocates to improve planning, access, and delivery of health services, thereby mitigating the longstanding global burden of pain.

Keywords: Pain, Quantitative Sensory Tests, Temporal Summation, Conditioned Pain Modulation, Pressure Pain Threshold

Introduction

Pain is a distinctly personal yet universal experience influenced by numerous factors beyond the correlate of sensory input and pathoanatomic tissue damage [1,2]. The International Association for the Study of Pain’s (IASP) most current definition of pain is “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage"[2]. On a global scale, chronic pain constitutes a prevalent and persistent global health issue, affecting approximately one in five adults worldwide which is equivalent to an estimated 1.5 billion individuals [3]. In 2021, approximately 20.9% of adults in the United States equating to an estimated 51.6 million individuals were affected by chronic pain [4]. There is an annual increase in new cases of chronic pain among adults in the US, more than other common chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, or depression [2-4]. Although its definition continues to evolve due to its complex etiology, pain is ubiquitous and imposes major global health burden from limitations in function and mobility, decreased quality of life, increased health care cost and lost productivity [1-4].

Many variables influence pain neurophysiology that contribute to the distinct and highly variable pain perception across individuals [2,5]. These include age, culture, health literacy, psychobehavioral status, life experiences, fatigue, support systems, and individual health status [1,2,4-6]. Pain is also mediated by the integrity and activity of the peripheral nociceptors and pain processing centers in the thalamus, medial reticular formation of the brain stem, including the lateral spinothalamic and medial spinoreticulothalamic pathways and the brain’s cortex [7-14]. Aberrations on these regions result in impaired processing of afferent input, with or without noxious stimuli or tissue damage, a feature also found in patients with Types I and II diabetes, fibromyalgia, and other chronic pain conditions [10,12-18].

Quantitative sensory testing (QST) constitutes a standardized, objective representation of the traditional neurological sensory examination, designed to systematically quantify sensory thresholds and provide reproducible data on somatosensory function [7,9,11]. Dysfunctions in QST have been used as predictors of chronic pain conditions such as fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, and low back pain, demonstrated as low pain threshold, impaired descending inhibition and delayed recovery from central sensitization [10,12,13,15,18-20]. Although inter-individual variability exists, aberrations in pain processing mechanisms exists and in chronic pain states versus pain-free controls [20,21]. Furthermore, several psychological factors such as catastrophizing behaviors and poor self-efficacy had been found to be predictors of pain [23,24]. However, the relative importance of integrated examination of psychosocial characteristics and sensory testing predictors has not been evaluated. Given the growing evidence on the multifactorial contributors to chronic pain, including psychosocial and neurophysiological pain mechanism, it is likely that both will have differential roles in clinical practice.

Prevention of the consequential impact of pain must include the influence of the pain processing mechanisms in identifying groups at risk for prolonged or chronic pain to address and mitigate its global impact through targeted strategies starting with local communities. The purpose of this study was to examine the association between individual characteristics, psychobehavioral factors and individual pain processing mechanisms using Quantitative Sensory Tests (QST) in healthy adults. Existing healthcare measures to identify individuals or groups at risk for chronic pain and its debilitating effect is currently sparse. Targeted and effective screening for prevention, including early identification and intervention of groups and communities at risk for prolonged pain, is an important aspect in helping promote public health across communities.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Study Design

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, and all participants were provided with, and completed the informed consent approved by the XXX Institutional Review Board, member of the XXX Health System. Forty-three healthy volunteers were enrolled in the study through verbal and written recruitment advertisements. Participant screening, enrollment and testing procedures were completed in one session at the XXX. All experimental pain testing procedures were conducted by the primary investigator who is a licensed Physical Therapist in the XXX, with clinical training and expertise in standardized QST procedures. Inclusion criteria were as follows: adults between the ages of 18 65, pain-free in any body region and not have received any type of intervention related to any ongoing medical diagnosis or painful conditions within the last 3 months. Subjects were excluded if pregnant, if with a history of trauma on the head and neck regions such as in a motor vehicular accident, surgery on the cervical spine and/or temporomandibular joint/s, progressive and/or non progressive disorders of the central nervous or immune systems, cervical spine instability, systemic and/or inflammatory disorders, TMJ inflammatory arthritis, osteoporosis, and malignancy.

Instruments and Outcome Measures

Completed and signed informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Intake form with demographic and health-related information were collected. Psychosocial measures of anxiety, depression, and pain catastrophizing were also collected using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), the Beck Depression Index (BDI) scale, and the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) respectively. Quantitative measurement of individual pain processing mechanisms was conducted using Quantitative Sensory Tests (QST) through measures of mechanical pressure pain threshold (PPT) to measure pain threshold, Temporal Summation to measure pain sensitization or level of pain sensitivity, and Conditioned Pain Modulation to assess pain modulation. Experimental pain induction was conducted using a calibrated mechanical pressure algometer (Pain Test™ FPX, Wagner Instruments, Greenwich, CT, US), consisting of a round rubber disk (1 cm2) attached to a digital pressure gauge that displays values in lb/cm2 ranging 0-100. Pressure algometer is a reliable instrument for PPT measurements across healthy, asymptomatic individuals [9,18,25]. The full testing protocol was conducted by the PI with clinical training and expertise in QST, consistent with the standardized protocol established by the German Research Network on Neuropathic Pain [9,25]. This protocol has been used in many investigations involving QST and pain across different populations, which includes a series of consistent testing methods designed to evaluate and quantify somatosensory performance in both large (Aβ fibers) and small sensory nerve fibers (Aδ and C fibers) [24,40]. Its primary goal is to identify alterations in sensory perception, including diminished sensitivity (such as hypoesthesia and hypoalgesia) or heightened sensitivity (such as hyperesthesia, hyperalgesia, and allodynia) [19-24]. It is a valid and reliable measure of somatosensory and pain processing function, although not currently widely used in clinical practice but largely used in research for its diagnostic and prognostic value, as well as evaluation of treatment effectiveness [10,11,13,15,18,22]. In particular, Temporal Summation (TS) and Conditioned Pain Modulation (CPM) has been used to predict the development of post-surgical clinical pain, chronic musculoskeletal pain, including neuropathies in neurologic and metabolic disorders [13,14,16,18,22].

Examiner recording form was used to record the QST pain outcomes: the PPT score on each of the three trials, including the TS and CPM scores. The QST pain assessment process started with the PPT assessment to determine each participant’s level of pain threshold. This threshold represents the level of pressure or noxious stimuli that an individual can tolerate until it is perceived to be “unpleasant or painful. Subjects were instructed to say the word “STOP!” when the threshold level was reached at which point the pressure was removed and recorded [36]. The incremental pressure application using the pressure algometer was increased at a rate of 1 lb/cm. The three measurements were assessed on the right upper trapezius muscle belly halfway between their origin on the spinous process of the seventh cervical vertebra and its insertion on the acromion. This test site was marked with an “X” using a skin marker to ensure consistency of experimental pain induction, with a one-minute rest period provided between each measurement to avoid cutaneous sensitization. The average of the three PPT measurements was used as the pain testing intensity in the TS and CPM testing protocol. The PPT, TS, and CPM have excellent interrater reliability and high test-retest reliability [9,10,12,14,40].

Temporal summation measured the ramping up of pain intensity during repeated experimental pain application to assess pain sensitization, which was completed three minutes after the final PPT was taken. Ten pressure pulses at PPT were administered over the right upper trapezius muscle belly, each for 1-second duration with a 1-second interstimulus interval. The electronic pressure algometer was used to ensure uniform pressure application and a timer was used to ensure uniform pressure rate and duration. Subjects were asked to verbally rate their level of discomfort at the first and tenth pressure pulses using the NPRS with anchors of 0 (“no pain at all”) and 10 (“worst possible pain”). Because the mechanical PPT assessment was used solely to determine each participant’s threshold for experimental pain induction required for TS and CPM testing and not to characterize peripheral or central pain mechanisms in our healthy sample the procedure was not administered at a remote or secondary body region. TS was calculated as pain rating on the tenth pressure pulse minus pain rating on the first pressure pulse. The CPM protocol was performed five minutes after the completion of the TS Test to prevent sensitization from prior pressure pain applications. Ischemic arm testing consisted of an inflatable pressure cuff (14.5 cm) placed on the left arm proximal to the cubital fossa and inflated to 240 mmHg at 20 mmHg/s or terminated when a pain level of 4/10 on the NPRS was achieved. This arm pressure was maintained for 60 seconds at which point the cuff was deflated and ten pressure pulses from a previously identified PPT intensity were performed immediately to the right upper trapezius muscle belly. Subjects were asked to verbally rate their level of discomfort at the first and tenth pressure pulse using the NPRS. CPM was calculated as pain rating on the tenth pressure pulse minus pain rating on the first pressure pulse.

The patient-reported psychosocial measures used in this study are validated and reliable clinical tools. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) is a commonly used outcome measure that assesses anxiety and distinguishes it from depressive syndromes [25,26]. The STAI has 20 items for assessing anxiety trait and 20 items for the state of anxiety [26]. Each item in the questionnaire is rated on a 4-point likert scale, where higher scores correspond to greater anxiety. The STAI is appropriate for those with at least a 6th-grade reading level and has excellent internal consistency, good test-retest reliability, and good construct validity [25,26]. The Beck Depression Index scale (BDI) assesses severity of depression [27-30]. It’s consists of 21-item multiple choice inventory of symptom severity based on a 4-point scale ranging between 0-3 points for each item. The scale’s interpretation of scores are as follows: 0-13=mild depression, 14-19=minimal depression, 20-28 =moderate depression, 29-63=severe depression [28,29]. The BDI scale has high specificity and sensitivity along with excellent internal consistency (0.9), excellent test-retest reliability (0.73-0.96), and high concurrent, content, and construct validity (0.77 to 0.93) 0[29,30]. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) is a psychobehavioral outcome measurement tool used to assess pain catastrophizing behaviors based on past pain experiences [31,32,33]. The tool is a 13-item instrument with a 4-point scale on the thoughts and feelings when experiencing pain. The PCS has excellent internal consistency (0.94), excellent test-retest reliability, and good construct validity (1.0) [31-34]. The Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) is a reliable (ICC = 0.67; [0.27 to 0.84]), responsive, and well-validated tool used to assess both clinical and experimental pain [35,36]. It is administered verbally using anchors of 0 (“no pain at all”) and 10 (“worst possible pain”). Given the well-established psychometric and clinimetric properties of the NPRS, it was used as the outcome measurement tool in the assessment of all pain outcomes from QST.

We employed descriptive statistics to characterize the sample’s demographic and clinical profile. Relationships between demographics and QST values from PPT, TS, and CPM were assessed using the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum and Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate. The BDI was categorized as ≤10 v. ≥11 points according to predetermined cutoff scores, consistent with the scale’s standard scoring criteria [23,24]. The PCS and STAI were grouped at their median given skewness in their distribution. Linear regression models were used to assess the joint relationship of patient characteristics and PPT. There was no missing data for demographic or outcome variables of interest. All analyses were conducted in R (3.6.2). This study employed a nonprobabilistic convenience sampling approach, primarily driven by clinical and logistical accessibility. As a result, formal sample size calculations were not performed, given the challenge of determining an effect size that would be considered clinically meaningful for external validity. Nonetheless, the study population was relatively homogeneous due to stringent inclusion criteria, which supports the use of a smaller sample size with minimal variance [37,38]. In addition, our sample size exceeded that of several comparable prior studies, thereby strengthening the statistical power of our analyses and improving the internal validity of the results [37,38].

Results

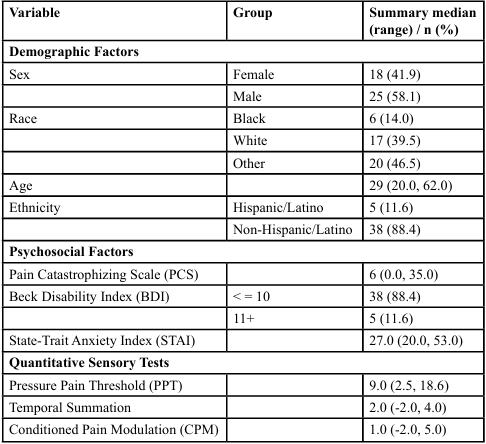

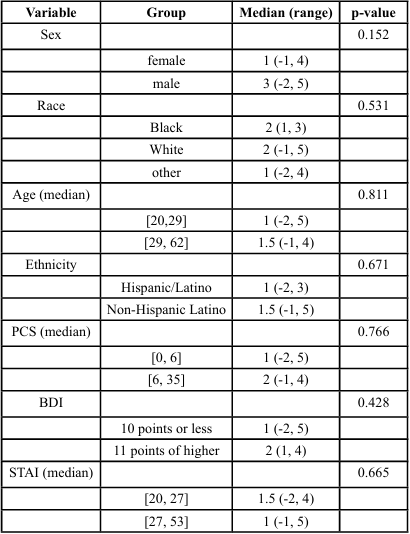

The study had 43 participants with 42% female, mean age of 29 years old (20,62), 12% Latino and 88% Non-Hispanic Latino. Races represented were Black, (14%), White (40%), and others (47%) consisting of Asian and Latin. Table 1 presents the sample’s full descriptive profile. All psychosocial measures were scored and interpreted based on each scale’s scoring and interpretation criteria. The median STAI and BDI scores were 27 points and 5 points, respectively, while the median PC score was 6 points. The BDI was categorized as ≤ 10 and ≥11 points, consistent with the questionnaire’s designated cutoff values [23,24]. Pain catastrophizing scores and STAI were grouped at the median values given the skewness in the distribution of these variables. There was no missing data for demographic or outcome variables of interest.

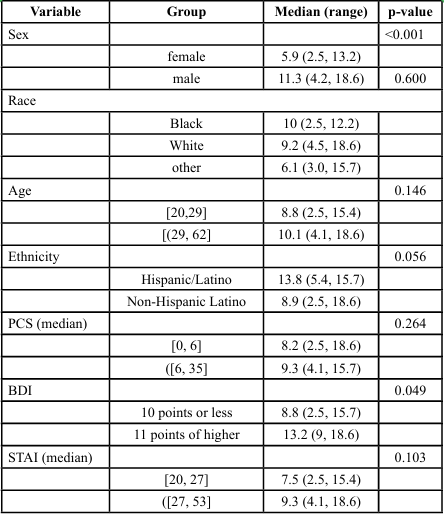

Linear regression models were used to assess the joint relationship of patient characteristics and PPT. Univariate analysis showed men and individuals with BDI scores of ≥11 points exhibited greater PPT values (p < 0.001 and p = 0.049 respectively). Hispanic/Latino subjects also tended to have higher PPT scores (p = 0.056). Non Hispanic/Latino subjects showed a predicted score of 3.3 lbs lower pain threshold than Hispanic/Latino subjects ([-6.1, -0.5], p = 0.024) as seen in Tables 2 and 3. Mechanical PPT scores were significantly different across sex and levels of depression. Joint multivariate model showed subjects with BDI of scores of ≥11 points tended to have 3.8 lbs. higher PPT values than those with scores ≤10 points ([1.2, 6.5], p = 0.004), while men had PPT values 4.1 lbs. greater than women (95% CI [2.8, 5.4], p < 0.001). Significant differences in TS of subjects with levels of pain catastrophizing was also seen (p=0.42) (Tables 4, 5). However, no significant outcomes were seen for CPM, although sex was approaching significance. Ethnicity showed fair correlation with PPT but unseen with regression analysis, suggesting that ethnicity must be accounted for as a covariate in the assessment of pain processing mechanism and pain outcomes.

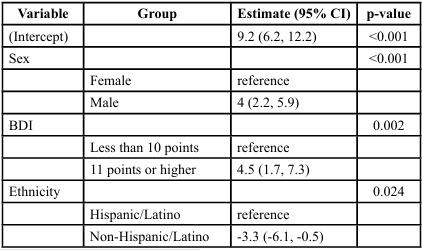

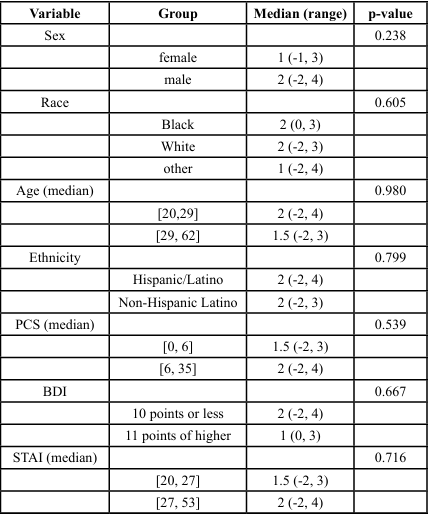

Multivariate analysis adjusting for sex, ethnicity, and BDI scores showed that the predicted mechanical pain threshold among men was 4 points higher than women (95% confidence interval [2.2, 5.9], p < 0.001). Those with BDI scores of ≥11 points had predicted pain threshold of 4.5 points higher than those with scores on BDI ≤ 10 ([1.7, 7.3], p = 0.002). Furthermore, non-Hispanic/Latino subjects have a predicted score of 3.3 points less than Hispanic/Latino subjects ([-6.1, -0.5], p = 0.024) (Table 5). There were no significant differences in TS or CPM across any other predictor variables or pain outcomes, as presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of demographic and psychosocial factors considered as predictor variables and pain measures as outcome variables

Table 2. Outcomes on the Association between Demographic and Psychosocial Variables with Pressure Pain Threshold (PPT) (lbs.)

Table 3. Outcomes on the Association between Demographic and Psychosocial Variables with Temporal Summation (TS)

Table 4. Outcomes on the Association between Demographic and Psychosocial Variables with Conditioned Pain Modulation (CPM)

Conclusion

Our findings provide preliminary evidence that sex, ethnicity, depressive symptoms, and pain catastrophizing behaviors may contribute to variability in pain threshold and sensitivity, reflecting the functional state of neural pain processing in otherwise healthy individuals. Quantitative sensory testing (QST) shows promise as a tool for detecting early alterations in pain processing among those at elevated risk for chronic pain, though its predictive utility warrants further investigation. Importantly, a distinct subgroup of asymptomatic participants demonstrated heightened pain sensitivity, reduced pain thresholds, and elevated depression and catastrophizing scores clinical features commonly observed in chronic pain populations [10,12,16,17,18,20]. These underrecognized psychosocial risk factors, coupled with impaired pain processing mechanisms in healthy individuals, highlight the need for strategies that enhance awareness, education, and screening, while expanding access to health and wellness resources across communities. Such efforts may reduce health disparities and ensure inclusion of populations vulnerable to adverse and prolonged pain experiences. More broadly, these findings underscore the importance of a multidimensional approach to chronic pain prevention and screening that can be initiated prior to pain onset, regardless of etiology. Community leaders, health advocacy groups, and health system administrators should prioritize comprehensive and innovative approaches to preventive care and accessible clinical pathways, thereby promoting public health and mitigating the burden of prolonged pain and disability.

Discussion

Effective prevention of pain’s debilitating impact must begin proactively prior to onset to reduce the likelihood of progression into chronic conditions. Translating advances in pain etiological mechanisms into practice requires implementation strategies that emphasize education, early screening, and timely intervention. Addressing pain demands a paradigm shift: it should no longer be regarded merely as a symptom, but as a complex and potentially persistent condition that is preventable yet requires evidence informed, comprehensive care. This includes integrating targeted health services and resources, such as non-opioid pharmacologic options, alongside behavioral and psychosocial approaches. Public health initiatives must also prioritize prevention, education, and equitable access to care, particularly in underserved communities where disparities in pain outcomes are most pronounced. By acknowledging the full biopsychosocial spectrum of pain’s progression and impact, health systems and communities can begin to mitigate its consequences, reduce long-term burden, and improve outcomes for individuals and society at large.

Our study has several limitations, including a small sample size and the absence of mechanical PPT assessment at a remote, secondary body region. These factors limit the generalizability of our findings and constrain our ability to determine whether the QST related aberrations in pain processing reflected peripheral or central mechanisms information that would have offered deeper insight into the pain profiles of our sample. However, the findings nonetheless provide valuable insight into pain processing mechanisms among asymptomatic, healthy individuals. These results may be particularly relevant for identifying subgroups with comparable demographic and psychosocial characteristics that mirror the biopsychosocial profiles observed in chronic pain conditions. Future research should further examine the utility of QST as an innovative outcome measurement tool for prevention, screening, classification, and intervention in populations at risk for adverse pain-related health outcomes. Advancing community health will require coordinated, targeted approaches across organizational, political, and interprofessional levels. Such efforts are essential to inform community-based public health planning and delivery, including education programs designed to directly address and reduce health disparities associated with the longstanding global burden of pain.

Authors’ Contributions:

Carla S. Enriquez PT, PhD, DPT, MS, OCS – research conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, manuscript preparation and edits

Musola Oniyide PT, DPT – data collection and manuscript preparation/edits

Christine Tolerico, PT, MS – data collection, analysis, and interpretation, manuscript preparation/edits

Nicole Rommer PT, DPT – data collection, manuscript preparation/ edits

Thomas Koc PT, DPT, PhD, OCS – data analysis, manuscript preparation/edits

John Lee, PT, DPT, PhD, OCS – data analysis, manuscript preparation/edits

Patrick Hilden, DrPH – data analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation/edits

Competing Interests:

All authors have reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission. All the authors have substantially contributed to the manuscript, per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria of authorship. Dr. Carla S. Enriquez declares no competing interest as a reviewer.

• Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

• Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

• Final approval of the version to be published; AND • Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgement:

Dr. Carla Enriquez acknowledges and values the support for clinical research from the administration and staff at Cooperman Barnabas Medical Center, Comprehensive Outpatient Rehabilitation Center, Department of Physical Therapy, Livingston, NJ.

References

Hansen, G. R., & Streltzer, J. (2005). The psychology of pain. Emergency Medical Clinic of North America. 23(2):339-348. View

Raja, S. N., Carr, D. B., & Cohen, M., et al. (2020). The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 161(9):1976 1982. View

Goldberg, D. S., McGee, S. J. (2011). Pain as a global public health priority. BMC Public Health. 11:770. Published 2011 Oct 6. View

Nahin, R. L., Feinberg, T., Kapos, F. P., Terman, G. W. (2023). Estimated Rates of Incident and Persistent Chronic Pain Among US Adults, 2019-2020. JAMA Netw Open. View

Garland, E. L. (2012). Pain processing in the human nervous system: a selective review of nociceptive and biobehavioral pathways. Prim Care. 39(3):561-571. View

Koppen, P., Dorner, T., Crevenna, R. (2018). Health literacy pain intensity and pain perception in patients with chronic pain. Wein Klin Wochenschr. 130(1-2):23-30. View

Nie, H. L., Graven-Nielsen, T., & Arendt-Nielsen, L. (2009). Spatial and temporal summation of pain evoked by mechanical pressure stimulation. Eur J Pain. 13(6):592-599 View

Mohammadi-Farani, A., Sahebgharani, M., Sepehrizadeh, Z., Jaberi, E., Ghazi-Khansari, M. (2010). Diabetic thermal hyperalgesia: Role of TRPV1 and CB1 receptors of periaqueductal gray. Brain research. 1328:49-56. View

Rolke, R., Baron, R., Maier, C., et al. (2006). Quantitative sensory testing in the German Research Network on Neuropathic Pain (DFNS): standardized protocol and reference values [published correction appears in Pain. 2006 Nov;125(1-2):197]. Pain. 123(3):231-243. View

Mata, J. Z., Azkue, J. J., Bialosky, J. E., et al. (2024). Restoration of normal central pain processing following manual therapy in nonspecific chronic neck pain. PloS one. 19(5):e0294100-e0294100. View

Mackey, I. G., Dixon, E. A., Johnson, K., Kong, J. T. (2017). Dynamic Quantitative Sensory Testing to Characterize Central Pain Processing. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (120). View

Kuppens, K., Hans, G., & Roussel, N., et al. (2018). Sensory processing and central pain modulation in patients with chronic shoulder pain: A case-control study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 28(3):1183-1192. View

Izumi, M., Hayashi, Y., Saito, R., et al. (2022). Detection of altered pain facilitatory and inhibitory mechanisms in patients with knee osteoarthritis by using a simple bedside tool kit (QuantiPain). Pain Rep. 7(3):e998. Published 2022 Apr 1. View

Sierra-Silvestre, E., Somerville, M., Bisset, L., Coppieters, M. W. (2020). Altered pain processing in patients with type 1 and 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of pain detection thresholds and pain modulation mechanisms. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 8(1):e001566. View

Siegenthaler, A., Schliessbach, J., & Vuilleumier, P. H., et al. (2015). Linking altered central pain processing and genetic polymorphism to drug efficacy in chronic low back pain. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 16:23. Published 2015 Sep 16. View

Hansen, L. E. M., Fjelsted, C. A., & Olesen, S. S., et al. (2021). Simple Quantitative Sensory Testing Reveals Paradoxical Co-existence of Hypoesthesia and Hyperalgesia in Diabetes. Frontiers in pain research (Lausanne, Switzerland). 2:701172- 701172. View

Treede, R.-D. (2019). "The role of quantitative sensory testing in the prediction of chronic pain." PAIN 160: S66-S69. View

Uddin, Z., and J. C., & MacDermid (2016). "Quantitative Sensory Testing in Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain." Pain Medicine, 17(9): 1694-1703. View

Petersen, K. K., O’Neill, S., Blichfeldt-Eckhardt, M. R., Nim, C., Arendt-Nielsen, L., Vægter, H. B. (2025). Pain profiles and variability in temporal summation of pain and conditioned pain modulation in pain‐free individuals and patients with low back pain, osteoarthritis, and fibromyalgia. European journal of pain. 29(3):e4741-n/a. View

Corrêa, J. B., Costa, L. O. P., de Oliveira, N. T. B., Sluka, K. A., Liebano, R. E. (2015). Central sensitization and changes in conditioned pain modulation in people with chronic nonspecific low back pain: a case–control study. Experimental brain research. 233(8):2391-2399. View

Larsen, D. B., Laursen, M., Edwards, R. R., Simonsen, O., Arendt-Nielsen, L., & Petersen, K. K. (2021). The Combination of Preoperative Pain, Conditioned Pain Modulation, and Pain Catastrophizing Predicts Postoperative Pain 12 Months After Total Knee Arthroplasty. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass). 22(7):1583-1590. View

Nahman-Averbuch, H., Nir, R., Sprecher, E., Yarnitsky, D. (2016). Psychological Factors and Conditioned Pain Modulation: A Meta-Analysis. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 32(6):p 541- 554, June 2016. View

Umeda, M., & Okifuji, A. (2023). Exploring the sex differences in conditioned pain modulation and its biobehavioral determinants in healthy adults. Musculoskeletal science & practice. 63. View

Weaver, K. R., et al. (2022). "Quantitative Sensory Testing Across Chronic Pain Conditions and Use in Special Populations." Frontiers in Pain Research Volume 2 - 2021. View

Stojanović, N., Ranđelović, P., & Nikolić, G., et al. (2020). Reliability and validity of the Spielberger’s State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) in Serbian university student and psychiatric non-psychotic outpatient populations. Acta Facultatis Medicae Naissensis. 37(2):149-159. View

Spielberger, C. D. (1983). State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults Sampler Set Manual, Instrument and Scoring Guide. Consulting Psychologists Press, INC. View

Geisser, M. E., Roth, R. S., & Robinson, M. E. (1997). Assessing depression among persons with chronic pain using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory: a comparative analysis. Clin J Pain. 13(2):163-70. View

Bautovich, A., Katz, I., Loo, C. K., & Harvey, S. B. (2018). Beck Depression Inventory as a screening tool for depression in chronic haemodialysis patients. Australasian psychiatry : bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 26(3), 281–284. View

Wang, Y. P., & Gorenstein, C. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: a comprehensive review. Braz J Psychiatry. 35(4):416-31. View

Khan, A. A., Marwat, S. K., Noor, M. M., & Fatima, S. (2015). Reliability and Validity of Beck Depression Inventory Among General Population In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad : JAMC, 27(3), 573–575. View

Osman, A., Barrios, F. X., Kopper, B. A., Hauptmann, W., Jones, J., & O’Neill, E. (1997). Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale. J Behav Med. 20(6):589-605. View

Ong, W. J., Kwan, Y. H., Lim, Z. Y., Thumboo, J., Yeo, S. J., Yeo, W., Wong, S. B., & Leung, Y. Y. (2021). Measurement properties of Pain Catastrophizing Scale in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Clinical rheumatology, 40(1), 295–301. View

Xu, X., Wei, X., & Wang, F., et al. (2015). Validation of a Simplified Chinese Version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale and an Exploration of the Factors Predicting Catastrophizing in Pain Clinic Patients. Pain Physician. 18(6):E1059-1072. View

Osman, A., Barrios, F. X., Kopper, B. A., Hauptmann, W., Jones, J., & O’Neill, E. (1997). Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale. J Behav Med. 20(6):589-605. View

Paice, J. A., & Cohen, F. L. (1997). Validity of a verbally administered numeric rating scale to measure cancer pain intensity. Cancer Nurs. 20(2):88-93. View

Young, I. et al. (2025). ‘Clinimetric analysis of the numeric pain rating scale, patient-rated tennis elbow evaluation, and tennis elbow function scale in patients with lateral elbow tendinopathy’, Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 41(8), pp. 1712–1720. View

Gupta, K.K., Attri, J.P., Singh, A., Kaur, H., & Kaur, G. (2016). Basic concepts for sample size calculation: Critical step for any clinical trials. Saudi J. Anaesth. 10, 328–331. View

Das, S., Mitra, K., & Mandal, M. (2016). Sample size calculation: Basic principles. Indian J. Anaesth. 60, 652–656. View