Journal of Rehabilitation Practices and Research Volume 7 (2026), Article ID: JRPR-192

https://doi.org/10.33790/jrpr1100192Research Article

The Anatomy of Assessment: Competency-Based Educational Outcomes in a Doctor of Physical Therapy Anatomy Course

Michael Morgan, PT, DPT, OCS1*, Jeb Helms, PT, DPT, EdD2, John Imundi, PT, DPT, EdD2, and Taylor Lane, PhD3

1Assistant Clinical Professor- Department of Physical Therapy & Athletic Training, Northern Arizona University, Phoenix Biomedical Campus, Phoenix, Arizona, United States.

2Associate Clinical Professor- Department of Physical Therapy & Athletic Training, Northern Arizona University, Phoenix Biomedical Campus, Phoenix, Arizona, United States.

3Assistant Research Professor- Department of Health Sciences, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Michael Morgan, PT, DPT, OCS, Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Physical Therapy & Athletic Training, Northern Arizona University, Phoenix Biomedical Campus, 435 N. 5th Street, Phoenix, AZ 85004, United States.

Received date: 13th November, 2025

Accepted date: 29th December, 2025

Published date: 01st January, 2026

Citation: Morgan, M., Helms, J., Imundi, J., & Lane, T., (2026). The Anatomy of Assessment: Competency-Based Educational Outcomes in a Doctor of Physical Therapy Anatomy Course. J Rehab Pract Res, 7(1):192.

Copyright: ©2026, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Introduction: As Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) programs increasingly explore competency-based education (CBE), the additional faculty time required for assessment remains a significant barrier. This study evaluates three CBE-aligned assessment design strategies within a first-semester anatomy course: (1) a combination of open- and closed-book summative assessments, (2) structured one-week summative assessment windows, and (3) learner choice in formative assessments. Each strategy was developed to reduce faculty workload while maintaining alignment with CBE principles.

Subjects: Sixty first-semester DPT students participated in a DPT anatomy course that utilized several CBE assessment principles offered within a Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education (CAPTE) accredited program.

Methods: This retrospective mixed-methods study analyzed assessment scores and survey responses from a redesigned CBE anatomy course. Data included scores from seven summative assessments (five open-book assessments offered within one-week windows and two closed-book exams), performance on twelve formative module assessments, and learner survey responses regarding perceptions of assessment design. Pearson correlation coefficients examined relationships between open- and closed-book summative performance and between formative assessment attempts and summative scores. Qualitative survey responses were analyzed thematically.

Results: Performance on open-book summative assessments was significantly correlated with closed-book midterm (r = 0.33, p = 0.01) and final exam scores (r = 0.52, p < 0.001), suggesting that open-book assessments can effectively support preparation for high stakes, closed-book evaluations. In contrast, the number of formative assessment attempts did not significantly correlate with summative exam performance. Qualitative feedback highlighted reduced stress, increased learner autonomy, and improved faculty-learner interactions. Learners also recommended more structured deadlines and additional closed-book formative assessments to better simulate high-stakes testing environments.

Discussion and Conclusion: Findings provide preliminary evidence that open-book summative assessments, structured assessment windows, and learner-driven formative opportunities can support learning and performance in a CBE anatomy course. Programs transitioning to CBE may benefit from integrating structured open- book assessments within anatomy curricula. Future research should explore how to optimize formative assessment design and validate assessment tools to enhance competency-based anatomy education.

Keywords: Competency-based education, open-book assessment, physical therapy anatomy, summative assessment, formative assessment, assessment window

Introduction

In line with other health professions, physical therapy (PT) educators are being urged to shift into a competency-based education (CBE) model to ensure that graduates demonstrate the knowledge, skills, and professional behaviors required for safe, effective practice [1-3]. Despite growing national attention, there are only a small number of published examples of physical therapy CBE curriculum design [4] and CBE clinical education tools, [5] and minimal published examples of CBE Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) course implementation [6].

At the course level, CBE shifts the focus from time-based progression to the demonstration of competence on a more flexible, individualized learning schedule than traditional models [7,8]. This approach allows learners to select study resources, and attempt assessments at their own pace, creating a personalized pathway to competency [9]. While this flexibility supports learner autonomy and self-regulation, it also introduces logistical challenges for faculty tasked with ensuring validity, equity, and feasibility of assessment across diverse learners. A primary goal of CBE is to ensure that graduates are adequately prepared to meet the evolving needs of health care systems [10]. To achieve this, assessments should closely reflect real-world clinical practice.

Although published reports of CBE in physical therapy exist, most describe hybrid program delivery or clinical education innovations, leaving residential course-level strategies underexplored [11]. Understanding how CBE can be implemented within a traditional, in-person DPT course is essential, as these settings face unique pedagogical and operational constraints compared with hybrid models. Recent frameworks, including the core components of CBE [12] and the domains of competence for DPT education [13] provide a structure for aligning assessment design with national priorities; however, empirical evidence demonstrating how these frameworks can be enacted within residential coursework is lacking.

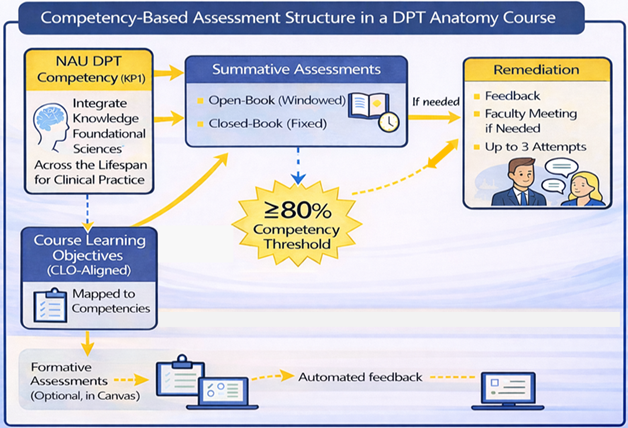

In this course, competency was operationalized as applied anatomical knowledge sufficient to support safe examination, movement analysis, and early clinical reasoning, consistent with foundational expectations for entry-level physical therapist education. Specifically, the course assessed Northern Arizona University (NAU) Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) clinical competencies, including Knowledge for Practice 1 (KP1): Integrate knowledge of foundational sciences across the lifespan for clinical practice. Course learning objectives (CLOs) were explicitly mapped to these competencies (e.g., CLO1: Describe the anatomy and physiology of the musculoskeletal system that impacts movement → KP1), and each assessment item was aligned to a CLO and its corresponding clinical competency. Although NAU’s competency framework was developed prior to the release of the American Physical Therapy Association’s (APTA) competency- based education (CBE) framework [14] in 2025, the constructs demonstrate substantial conceptual overlap, particularly within the Knowledge for Practice domain. Accordingly, the assessment redesign was intentionally structured to evaluate whether flexible, criterion-referenced assessment strategies could support learner demonstration of competency while maintaining psychometric rigor and feasibility in a residential anatomy course.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the implementation of three assessment strategies designed to operationalize CBE principles within a first-semester DPT anatomy course: (1) a combination of open- and closed-book summative assessments to balance accessibility and rigor; (2) structured one week summative assessment windows that provide flexibility while maintaining pacing; and (3) learner choice in formative assessments to promote self-directed learning.

Each assessment design feature in this study was developed to operationalize core components of competency-based education, including learner-centeredness, flexibility, and programmatic assessment [4,12,13]. Open- and closed-book summative assessments provided complementary measures of anatomical competence by balancing knowledge retrieval and clinical application. Structured one-week summative assessment windows supported flexible pacing within a fixed curricular progression, aligning with the principle of “flexible time, fixed competence.” Learner choice in formative assessments promoted self-regulated learning and feedback-driven improvement, consistent with programmatic assessment frameworks in health professions education [15,16].

Review of Literature

Assessment design in competency-based education must balance formative and summative approaches while considering the impact of open- and closed-book formats. Open-book assessments are often perceived as less stressful, allowing learners to reference materials and apply knowledge in a way that mirrors clinical decision-making [17]. However, while open-book exams may lead to higher grades and increased learner confidence, they do not necessarily improve long- term retention, as learners may rely too heavily on external resources rather than internalizing key concepts [18,19]. In contrast, closed- book assessments promote active retrieval, reinforcing knowledge retention through the testing effect [20]. Given that competency based anatomy education requires both foundational knowledge and clinical application, using a combination of open- and closed-book assessments can help ensure both accessibility and retention [21].

Beyond exam format, formative and summative assessments play distinct but complementary roles in CBE. Formative assessments provide ongoing feedback, allowing learners to track their progress and refine their understanding without the pressure of grades [22]. These assessments are designed to guide learners toward competency by offering low-stakes opportunities for improvement. Summative assessments, on the other hand, serve as high-stakes evaluations that determine whether learners have achieved the required competencies for professional practice [23,24]. In a competency-based anatomy course, integrating structured formative assessments alongside well-designed open- and closed-book summative assessments can create an optimal learning environment that fosters both immediate comprehension and long-term retention.

Designing authentic assessments within a CBE framework poses logistical challenges for PT anatomy educators [11,25]. Ideally, authentic assessments replicate real-world clinical tasks through simulation, workplace-based assessment, or direct observation [26]. Multiple-choice questions, even when clinically contextualized, primarily assess cognitive application rather than performance. However, when structured as case-based questions and supported by videos and images, these multiple-choice assessments approximate authentic assessment more closely than traditional knowledge- based multiple choice assessments as they require learners to apply anatomical concepts in clinically relevant contexts [11]. Other key logistical considerations include determining the appropriate balance between formative and summative assessments, deciding which, if any, should be open-book, and evaluating whether flexible due dates enhance learning. Taken together, the literature suggests that (1) mixed open-/closed-book strategies may support application and retention, (2) intentional formative design is central to programmatic assessment, and (3) structured flexibility can improve learner experience but requires careful logistics. These insights directly inform the assessment strategies examined in the present study.

Subjects

Participants were 60 first-semester DPT learners enrolled in Movement Sciences I (MS1), an integrated anatomy course within a fully competency-based DPT curriculum. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board as exempt (Protocol 2252057-2). Learners were informed that participation was voluntary and that their course grades would not be affected by their decision to participate. All students were given the opportunity to provide anonymous feedback on the CBE assessment process through an end-of-course survey and could separately elect to allow their de- identified performance data to be used for research. Sixty of 63 enrolled learners provided survey feedback, and 57 consented to inclusion of their de-identified performance data.

Methods

CBE Anatomy Course Structure

The MS1 course is an integrated anatomy course that combines elements of biomechanics, physiology, human development, and introductory manual therapy content. The course is 8 credit hours and is offered in the first semester of the two-year fully competency- based curriculum within a Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education (CAPTE) accredited DPT program. Course faculty planned MS1 using a backward design process focused first on desired learner outcomes at course completion. Accordingly, learners were encouraged to take an individualized path to obtain those outcomes. For example, learners with strong anatomical backgrounds were encouraged to attempt assessments when they felt ready, whereas learners with less experience were encouraged to spend more time studying before attempting assessments. All learners were given the opportunity to repeat any summative assessment up to three times, with the focus on obtaining competence rather than the number of attempts required to be successful.

The first iteration of MS1 was delivered in a hybrid online format in the spring of 2024. While both faculty and learner experiences with the CBE model were overall positive, logistically the lack of due dates was challenging [6]. In the initial iteration of MS1, learners were able to submit any of their authentic assessments at any time up until the final week of class. Over 70% of learners strongly agreed that the flexibility of when to submit the summative assessments (integral to the CBE model) [7] supported their learning. However, many learners expressed a desire for 'more structure and stricter deadlines' in their course feedback. Additionally, faculty felt that the lack of any due dates during the semester itself limited the opportunities for the coaching process.

Re-Designed Assessment Process

In response, the assessment process was re-designed for learners who took MS1 in the fall of 2024. Instead of being able to submit authentic assessments at any point during the semester, learners were given 1 week assessment windows (defined as flexible, time- bound periods during which a summative assessment could be submitted) throughout the semester where they could submit each authentic assessment. Learners still had the flexibility to submit that assessment at any time during that 1-week window. Competency was defined as achieving a score of ≥80% on each summative assessment; learners scoring below 80% were permitted up to three attempts, with structured feedback/coaching between attempts. If a learner did not submit their assessment within either the first or second assessment window, they forfeited one of their three assessment attempts. Faculty had 72 business hours from submission to return feedback to learners. Learners were then offered an opportunity to meet with their faculty grader before a second assessment attempt. If a learner required a third attempt, they had a mandatory meeting with the course lead but did not have a set window for completion. Although learners had flexibility within one-week assessment windows, all summative assessments were required to be completed by the end of the semester, and progression to subsequent courses was not accelerated based on early completion.

Assessment Description

The second iteration of MS1 consisted of seven authentic assessments. Two of those assessments were closed-book multiple choice exams delivered in person and designed to replicate the testing environment of the NPTE exam. All multiple-choice exam questions were reviewed by NPTE question writers who were not part of the primary course faculty or involved in teaching content within the course. All the other MS1 authentic assessments were open-book auto-graded 30-40 question multiple choice authentic assessments. Learners were encouraged to complete all formative assessments and to complete the open-book summative assessments however they felt would best prepare them for the closed-book summative midterm and final assessments. Therefore, faculty did not encourage or limit the number of resources learners utilized during formative or open book summative assessments. Closed-book midterm and final were completed in a proctored environment without resources and a 90 second time limit per question. This closed-book testing format was designed to prepare them to sit for the National Physical Therapy Examination (NPTE).

In an effort to make the CBE assessments authentic to clinical practice, [27] each question focused on clinical scenarios. Through videos and images, learners had to apply their anatomical knowledge to answer questions like what nerve innervates the muscle that is being stretched in this picture? Items of this type were intended to build contextual anatomical competence simulating how they might apply that in clinical situations [27,28]. While those multiple-choice questions were designed to emphasize application and clinical context, they remain limited compared to other performance-based assessments such as simulation or observed structured clinical examinations(OSCE) [26].

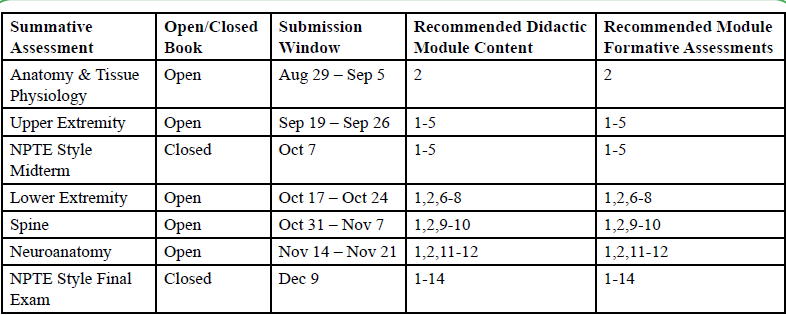

As faculty redesigned the assessment structure, they grappled with whether all multiple-choice summative exams should be closed- book. However, logistical constraints within the assessment window approach made it difficult to offer individually-scheduled, proctored closed-book exams while preserving the flexibility central to the CBE model. To balance rigor with accessibility, faculty implemented both open- and closed-book summative assessments. Open-book exams were available during flexible 1-week assessment windows, while closed-book exams took place on fixed dates [Table 1]. This approach allowed learners to maintain autonomy in pacing while enabling faculty to examine how performance on open-book assessments related to outcomes on closed-book exams [Figure 1].

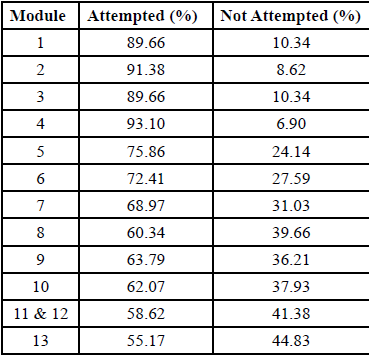

To better prepare learners for success on those authentic assessments, faculty introduced new formative assessments in the second iteration of MS1. Each assessment featured 20 multiple-choice questions targeting foundational anatomical knowledge, such as identifying the origin of specific muscles. Formative assessments were embedded within asynchronous Canvas modules aligned with course content and were intentionally sequenced alongside in-person synchronous sessions; learners were encouraged to complete formative assessments before, during, or after the corresponding synchronous instruction, while retaining autonomy over timing and participation. Learners could attempt them as many times as they wished, and while faculty would encourage participation, completion was not required.

Because both the formative assessments and the summative assessment windows were newly introduced in the residential version, it was unclear whether engagement with formative assessments or success on open-book exams would predict performance on the high stakes closed-book assessments.

Data Collection

Learners were given the opportunity to provide anonymous feedback on the CBE assessment process, as well as separately decide whether to share their grades with the research team; 60 of 63 enrolled learners provided survey feedback and shared grades. Learners answered a mixture of Likert and open-ended questions on their perceptions of the MS1 assessment process including open-book versus closed book, the CBE process, and their perceptions of the flexible due date policy.

Fifty-seven learners opted into the study and gave permission for their performance on the following assessments to be collated: 1) the twelve, 20-item multiple choice module formative assessments 2) the seven authentic assessments in the course 3) the number of attempts (1-3) it took them to pass each authentic assessment 4) the submission date of all open-book authentic assessments. A member of the research team linked that data to each learner and then deidentified all learner information for data analysis.

Quantitative Analysis Methods

Statistical Analysis

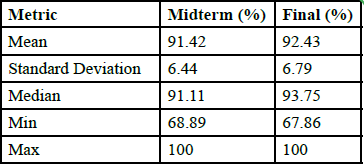

Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficients were used to examine the relationship between open-book summative assessments and midterm and final exam performance [Table 2] to determine whether success in open-book assessments predicted performance on closed-book exams. Pearson’s correlation was also applied to analyze the relationship between formative assessment attempts [Table 3] and midterm and final assessment performance. This test was selected for its ability to measure the strength and direction of linear relationships between continuous variables. Correlation significance was determined using p-values, with a threshold of p<0.05 considered statistically significant.

Quantitative Results

“Ninety-eight percent of learners agreed the flexible due dates reduced stress, and 100% reported that the flexibility helped them manage their time more effectively.

Correlations Between Open Summative Assessments and Closed Midterm and Final

• Summative Assessments 1 & 2 (combined) significantly correlated with the midterm (r=0.33, p=0.01)

• Summative Assessments 4, 5, & 6 (combined) were significantly correlated with the final (r=0.52, p<0.001)

Correlations Between Formative Assessment Attempt and Closed Midterm and Final

• Attempts for Modules 1-5 vs. Midterm: Not significant (r=0.14, p=0.28)

• Attempts for Modules 6-13 vs. Final: Not significant (r=0.07, p=0.61)

• Attempts for all Modules vs. Final: Not significant (r=0.05, p=0.70)

When asked about the impact of open-book assessments on closed book performance, 92% of learners reported that their performance on open-book assessments influenced their success on closed-book exams. However, 33% of learners stated that their preparation for open-book assessments did not mirror their preparation for closed book exams.

Qualitative Analysis Methods

We conducted thematic analysis of qualitative data from open ended survey responses to identify key trends and insights. Thematic analysis followed Braun and Clarke's six-phase framework: (1) familiarization with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report [29].

A primary researcher conducted initial coding, categorizing responses into preliminary themes. To ensure reliability and reduce potential bias, two additional researchers independently reviewed the coded data and provided feedback. Any discrepancies in coding or theme identification were discussed until consensus was reached. Themes were finalized based on frequency, richness of responses, and relevance to the study's focus.

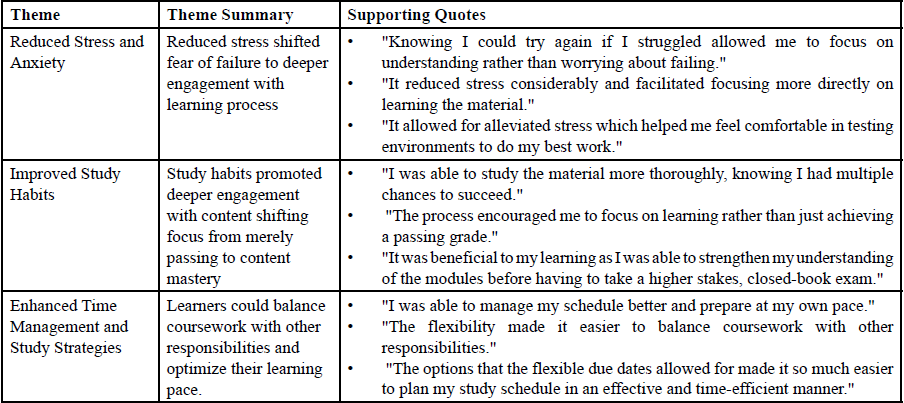

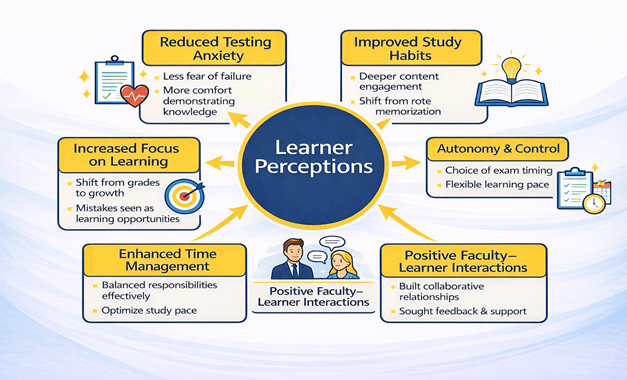

Codes were then categorized into six overarching themes that captured learner perceptions of the assessment structure: (1) Reduced Stress and Anxiety, (2) Improved Learning Outcomes, (3) Enhanced Time Management and Study Strategies, (4) Increased Self-Efficacy and Confidence, (5) Greater Autonomy and Personalization of Learning, and (6) Positive Faculty-Learner Interactions. Representative quotes were selected to illustrate key points within each theme.

In addition to open-ended responses, learners provided Likert scale ratings on various aspects of the competency-based assessment structure, offering quantitative insights into their experiences.

Qualitative Results

In addition to the Likert-scale responses, thematic analysis of open ended feedback highlighted six major themes which are presented below in Table 4. and Figure 2.

Discussion

The shift toward competency-based education (CBE) in physical therapy requires diverse assessment strategies to ensure learners develop both foundational knowledge and clinical reasoning skills. This model necessitates that faculty transition from primarily delivering content in a time-based curriculum to serving as coaches who guide learners toward demonstrating competence [11,23,30,31]. However, this coaching model often demands more faculty time and intentional assessment design [23,24]. As interest in CBE continues to grow within physical therapy, understanding how different assessment formats impact learning, performance, and workload is critical. Epstein [24] highlights that competency-based assessment should integrate multiple assessment methods to ensure comprehensive evaluation of clinical competence, supporting our rationale for incorporating diverse assessment formats.

Our findings offer preliminary descriptive insights into how selected assessment strategies align with competency-based education principles. Van Melle et al. describe the core components of CBE, including learner-centeredness, flexibility, and programmatic assessment, all of which informed the design of assessment windows and multiple attempts in this study [12]. Similarly, Knox et al. outlined the domains of competence for DPT education, emphasizing that assessment should span foundational knowledge, clinical reasoning, and professional behaviors [13]. The integration of open-book and closed-book formats within assessment windows aligns with these frameworks by supporting both knowledge retrieval and application in ways that mirror clinical practice.

This study explored learner feedback and performance on three potential CBE assessment strategies: (1) A combination of open- and closed-book summative assessments, (2) One-week assessment windows and (3) learner choice in the formative assessment process.

Open vs. Closed-Book Summative Assessments

Our primary research question explored whether open-book summative assessments correlated with performance on closed- book exams. The results indicate a significant positive correlation, suggesting that well-designed open-book summative assessments can serve as a valuable tool for reinforcing knowledge and preparing learners for high-stakes, closed-book assessments. This approach reflects prior research emphasizing the importance of assessment formats that promote active recall and deeper cognitive engagement, reinforcing the value of using both open-book and closed-book assessments within a CBE course [15,19,21].

Past research has identified high levels of learner anxiety with traditional closed-book anatomy assessments [32,33]. To reduce this stress, course faculty introduced open-book summative assessments. This approach aimed to not only decrease anxiety but also support long-term retention and more opportunities for knowledge application [18]. Offering individually-scheduled, proctored closed-book exams for 63 learners would have undermined the flexibility central to the CBE model. Faculty considered delivering all summative assessments in a closed-book format within flexible windows but ultimately chose a hybrid approach. In this design, open book assessments were scheduled within flexible windows, while closed-book NPTE-style exams occurred on fixed dates. The strong correlation observed between open- and closed-book performance in our study mirrors prior findings from nursing and medical education research demonstrating that open-book assessments can complement assessment programs and are not associated with worse closed-book performance [17,18,21]. These results also align with evidence that retrieval-based strategies, including open-ended testing, enhance long-term retention and problem-solving skills [19].

One Week Assessment Windows

Learner feedback offered valuable insight into the use of assessment windows. Assessment windows were helpful in addressing the learner pacing concerns identified in the first iteration of the course where assessments were able to be turned in at any point during the semester [6]. Both faculty and learner feedback around the use of assessment windows in this course was highly positive. Learner perspectives in our study echoed key themes identified by the process outlined by Barua and Lockee, [34] including reduced stress, increased autonomy, and improved faculty-learner interactions when flexible assessments are implemented. While most learners found flexible due dates beneficial, some expressed a desire for more structured deadlines or additional closed-book formative assessments to better simulate high-stakes exam conditions. These findings underscore the importance of balancing flexibility with structure in competency-based assessment models to optimize learner learning and performance.

As one of the first Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) programs to implement a competency-based curriculum, our study contributes to the growing discussion on how to design logistically feasible and effective assessments in this emerging educational model. Jensen et al. specifically called for PT CBE implementation research that provides evidence on how the timing of assessments influences their reliability and what faculty support structures are associated with successful CBE implementation [3].

Learner Choice in Formative Assessment Process

Finally, we also examined whether engagement with formative assessments predicted summative assessment performance. Formative assessments give learners the opportunity to practice retrieval-based assessment in a low-stakes environment [35] and are an important component within the CBE medical model [16,36,37]. The strategic design of formative assessments within a programmatic assessment model to support learner success on summative assessments helps to maximize their impact [15]. Formative assessments within CBE provide the learner a choice to complete them since they do not affect course grade. However, within physical therapy CBE, there are currently no studies examining the relationship between engagement with formative module assessments and learner performance on summative assessments. While prior research outside of PT suggests that formative assessments can enhance learning, [38,39] our results did not demonstrate a significant correlation between formative assessment attempts and midterm or final exam scores. One possible explanation is that learners leveraged prior knowledge or adopted alternative study strategies aligned with their self-perceived needs, highlighting a key CBE principle: the learner’s ability to determine how they engage with material based on prior experience and perceived competence [37]. Another explanation is that the declining completion rates of formative assessments (from 93% in early modules to 55% in later modules) suggest that learner autonomy may reduce engagement without grade incentives potentially highlighting a potential tension between learner flexibility and accountability in CBE-based assessments.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it focuses on a single foundational anatomy course, which may not reflect the broader impact of competency-based assessment strategies in more clinical application courses in the curriculum. Second, given the descriptive, single-cohort design and absence of a comparison group, correlation analysis should be interpreted as preliminary evidence rather than conclusive. Third, although the exam questions were designed to assess clinical reasoning and anatomical application, they were not externally validated, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Additionally, all assessments were given in a multiple choice format which constrains authenticity. While multiple-choice questions can approximate clinical reasoning through cases, they do not replicate real-world performance in the same way that simulation or workplace-based assessments would. Multiple- choice assessments primarily address the ‘knows’ and ‘knows how’ levels of Miller’s pyramid whereas simulation and workplace-based assessments are better suited for evaluating the higher ‘shows how’ and ‘does’ levels of competence [26].

The evaluation primarily addressed the first two levels of Kirkpatrick’s model: Level 1 (Reaction), through learner feedback on assessment design, and Level 2 (learning) 40 through analysis of performance on formative and summative assessments. However, it did not assess Level 3 (Behavior) or Level 4 (Results), such as how learners apply anatomical knowledge in clinical settings or long-term outcomes like NPTE pass rates. Without those longer-term outcomes, it remains unclear whether anatomy assessment performance translates into improved clinical competence.

Additionally, at the time of course implementation, the national physical therapy competency framework and EPA structure had not yet been published [14]. As such, alignment between course design and professional expectations was not intentional but emerged organically. Future iterations of the course should explicitly map learning outcomes and assessments to the established competencies and EPAs to ensure consistency with national standards and support longitudinal tracking of learner development.

Conclusion

Overall, this study provides preliminary short-term evidence that incorporating open-book summative assessments within assessment windows may provide a feasible strategy for balancing flexibility and rigor in a CBE curriculum. For programs considering a transition to CBE, these findings suggest that (1) open- and closed-book summative assessments may help balance accessibility and rigor, (2) structured one-week assessment windows may offer flexibility while maintaining learner pacing, and (3) providing learner choice in formative assessments can promote autonomy. Future research should further explore the role of formative assessments in competency-based learning and identify best practices for optimizing assessment design in DPT education. Additionally future studies should examine other subject areas within PT education and incorporate validated assessment tools to strengthen the reliability of results. Specifically, evaluating learner performance beyond the classroom including long-term anatomical knowledge retention as well as clinical behavior and licensure success will be essential to fully understand the effectiveness of the potential CBE assessment strategies presented here.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the use of the Research Capacity Core and Technical Assistance Group Service Center support and facilities of the SHERC at Northern Arizona University (U54MD012388).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was reviewed and approved as exempt by the Northern Arizona University Institutional Review Board (Protocol #2252057-2).

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design, data collection, data analysis, drafting of the manuscript, critical revisions, and approved the final version for submission.

Conflicts of Interest/Disclosures:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Timmerberg, J. F., Chesbro, S. B., Jensen, G. M., Dole, R. L., & Jette, D. U. (2022). Competency-based education and practice in physical therapy: It’s time to act! Phys Ther. 102(5):pzac018. View

Chesbro, S. B., Jensen, G. M., & Boissonnault, W.G. (2018). Entrustable professional activities as a framework for continued professional competence: is now the time? Phys Ther. 98(1):3-7. View

Tovin, M. M. (2022). Competency-based education: A framework for physical therapist education across the continuum. Phys Ther. 102(102):1-3. View

Schmidt, C. T., Knox, S., Baldwin, J., Gross, K. D., Tang, J., & Jette, D. U. (2024). Developing a competency-based outcomes framework for doctor of physical therapy Education. Health Prof Educ. 10(3). View

Holleran, C., Konrad, J., Norton, B., Burlis, T., & Ambler, S. (2023). Use of learner-driven, formative, ad-hoc, prospective assessment of competence in physical therapist clinical education in the United States: a prospective cohort study. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 20:36-36. View

Helms, J., and S. Donovan. (2026). “ Shifting Anatomy Away From a Time-Based Model: Competency-Based Education Insights for Anatomy Educators.” Clinical Anatomy 39, no. 1: 60–71. View

Motivating students in competency-based education programmes: designing blended learning environments | Learning Environments Research. Accessed April 3, 2025. View

Frank, J. R., Snell, L. S., Cate, O. T., et al. (2010). Competency- based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 32(8):638-645. View

Hennus, M. P., Jarrett, J. B., Taylor, D. R., & Ten Cate, O. (2023). Twelve tips to develop entrustable professional activities. Med Teach. Published online 2023:1-7. View

Janssens, O., Embo, M., Valcke, M., & Haerens, L. (2023). When theory beats practice: the implementation of competency based education at healthcare workplaces. BMC Med Educ. 23(1):484. View

Helms, J., Conn, L., Sheldon, A., DeRosa, C., & Macauley, K. (2026). Clinical anatomy in a physical therapist competency-based education course: challenges and solutions. Journal of Physical Therapy Education. Published online January 15, 2026. View

Van Melle, E., Frank, J. R., & Holmboe, E. S., et al. (2019). A Core Components Framework for Evaluating Implementation of Competency-Based Medical Education Programs. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 94(7):1002-1009. View

Knox, S., Bridges, P., & Chesbro, S., et al. (2025). Development of Domains of Competence and Core Entrance-to-Practice Competencies for Physical Therapy: A National Consensus Approach. J Phys Ther Educ. Published online June 3. View

Competency-Based Education in Physical Therapy: Essential Outcomes for Physical Therapist Entrance Into Practice. A Report from the American Physical Therapy Association. Accessed September 12, 2025. View

Schuwirth, L. W. T., Van der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2011). Programmatic assessment: From assessment of learning to assessment for learning. Med Teach. 33(6):478-485. View

Lockyer, J., Carraccio, C., & Chan, M. K., et al. (2017). Core principles of assessment in competency-based medical education. Med Teach. 39(6):609-616. View

Agarwal, P. K., Karpicke, J. D., Kang, S. H. K., Roediger III, H. L., & McDermott, K. B. (2008). Examining the testing effect with open- and closed-book tests. Appl Cogn Psychol. 22(7):861-876. View

Johanns, B., Dinkens, A., & Moore, J. (2017). A systematic review comparing open-book and closed-book examinations: Evaluating effects on development of critical thinking skills. Nurse Educ Pract. 27:89-94. View

Larsen, D. P., Butler, A. C., & Roediger, H. L. (2009). Repeated testing improves long-term retention relative to repeated study: a randomised controlled trial. Med Educ. 43(12):1174-1181. View

Ariel, R., & Karpicke, J. D. (2018). Improving self-regulated learning with a retrieval practice intervention. J Exp Psychol Appl. 24(1):43-56. View

Heijne-Penninga, M., Kuks, J. B. M., Schönrock-Adema, J., Snijders, T a. B, & Cohen-Schotanus, J. (2008). Open-book tests to complement assessment-programmes: analysis of open and closed-book tests. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 13(3):263-273. View

Carless, D. (2015). Excellence in university assessment: learning from award-winning practice. Routledge. View

Ten Cate, O., & Scheele, F. (2007). Competency-based postgraduate training: can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice? Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 82(6):542- 547. View

Epstein, R. M. (2007). Assessment in medical education. N Engl J Med. 356(4):387-396. View

Jalali, A., Jeong, D., & Sutherland, S. (2020). Implementing a competency-based approach to anatomy teaching: beginning with the end in mind. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 7:2382120520907899. View

Ten Cate, O., Carraccio, C., & Damodaran, A, et al. (2021). Entrustment decision making: extending miller’s pyramid. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 96(2):199-204. View

Nurunnabi, A. S. M., Rahim, R., & Alo, D., et al. (2023). ‘Authentic’ Assessment of clinical competence: where we are and where we want to go in future. Mugda Med Coll J. 6(1):37 43.

Ten Cate, O., Khursigara-Slattery, N., Cruess, R. L., Hamstra, S. J., Steinert, Y., & Sternszus, R. (2024). Medical competence as a multilayered construct. Med Educ. 58(1):93-104. View

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 3(2):77-101. View

Gugapriya, T., Dhivya, M., Ilavenil, K., Vinay, K. (2024). Strength weakness opportunities challenge analysis of implementing competencybased medical education curriculum: Perspectives from anatomy specialty. J Krishna Inst Med Sci Univ. 13(1):25-36. View

Black, K., Feda, J., Reynolds, B., Cutrone, G., & Gagnon, K. (2024). Academic coaching in entry-level doctor of physical therapy education. J Phys Ther Educ. Published online October 16, 2024. View

Fabrizio, P. A. (2013). Oral anatomy laboratory examinations in a physical therapy program. Anat Sci Educ. 6(4):271-276. View

Schwartz, S. M., Evans, C., & Agur, A. M. R. (2015). Comparison of physical therapy anatomy performance and anxiety scores in timed and untimed practical tests. Anat Sci Educ. 8(6):518-524. View

Barua, L., & Lockee, B. (2025). Flexible assessment in higher education: a comprehensive review of strategies and implications. TechTrends. Published online February 1. View

Sonnleitner, K., & Ruffeis, D. (2023). The role of formative assessments in competency-based online teaching of higher education institutions. In: Wolf B, Schmohl T, Buhin L, Stricker M, eds. From Splendid Isolation to Global Engagement. Vol 6. TeachingXchange. wbv Publikation:129-145. View

Wagner, N., Acai, A., & McQueen, S. A., et al. (2019). Enhancing formative feedback in orthopaedic training: development and implementation of a competency-based assessment framework. J Surg Educ. 76(5):1376-1401. View

Thangaraj, P. (2021). Concept of Formative assessment and Strategies for its effective implementation under competency based medical education: A review. Natl J Res Community Med. 10:16-24. View

Zhang, N., & Henderson, C. N. R. (2015). Can formative quizzes predict or improve summative exam performance? J Chiropr Educ. 29(1):16-21. View

Pawlow, P. C., & Griffith, P. B., (2024). Student-authored multiple-choice questions: an innovative response to competency-based education. J Nurs Educ. Published online December 10:1-4. View

Kirkpatrick, J. D.(2016). Kirkpatrick’s Four Levels of Training Evaluation. Alexandria, VA : ATD Press. View