Journal of Rehabilitation Practices and Research Volume 7 (2026), Article ID: JRPR-194

https://doi.org/10.33790/jrpr1100194Review Article

Addressing Spirituality in Occupational Therapy Education

Roblin C. Fenters1*, OTD, MSOT, OTR/L, and Michelle Woodbury2, PhD, OTR/L

1Assistant Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy, Francis Marion University in Florence, South Carolina, United States.

2Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy, Medical University of South Carolina,United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Roblin C. Fenters, OTD, MSOT, OTR/L, Assistant Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy, Francis Marion University in Florence, South Carolina, United States.

Received date: 22nd September, 2025

Accepted date: 06th January, 2025

Published date: 09th January, 2026

Citation: Fenters, R. C., & Woodbury, M., (2026). Addressing Spirituality in Occupational Therapy Education. J Rehab Pract Res, 7(1):194.

Copyright: ©2026, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Spirituality, a recognized client factor in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF), remains underrepresented in occupational therapy education and practice despite its critical role in holistic care and patient recovery. This project addresses the educational barriers namely, lack of confidence, self-awareness, and knowledge that hinder occupational therapy practitioners and students from effectively evaluating and treating spiritual needs. Through a quality improvement project, a Spirituality Unit of Instruction was developed and implemented in an entry-level occupational therapy neuro-rehabilitation course at a university in the southern United States. Grounded in adult learning theories and the Subject-Centered Integrative Learning Model (SCIL-OT), the unit included experiential activities, reflective exercises, and case based learning. Quantitative and qualitative data revealed significant increases in students’ perceived preparedness, confidence, and knowledge regarding spirituality in practice. Notably, confidence in evaluating spiritual needs rose from 13% to 92%, and awareness of personal biases increased from 30% to 92%. The project culminated in faculty-approved guidelines for integrating spirituality into entry level occupational therapy curricula, offering a replicable model for enhancing holistic, client-centered care. This work contributes to the growing evidence base supporting spirituality in occupational therapy and proposes a scalable educational solution to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

Introduction

The purpose of this quality improvement project was to develop guidelines for the inclusion of a spirituality unit of instruction in an entry level occupational therapy (ELOT) neurorehabilitation course. The unit of instruction addressed the educational barriers of perceived confidence, self-awareness, and knowledge that hinder the incorporation of spirituality in occupational therapy (OT) practice.

This project was based on “spirituality” as a client factor in the OT Practice Framework (OTPF) [1] and as the core of an individual in the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance & Engagement (CMOP-E). Spirituality is defined by the model’s creators as “a pervasive life force, source of will and self-determination, and a sense of meaning, purpose, and connectedness that people experience in the context of their environment”[2]. Occupational therapists have a role of enabling client-centered occupational performance and engagement through facilitation of the intricate balance between person (with spirituality centrally), occupation (self-care, leisure, productivity), and (cultural, physical, social, and intellectual) environment [2].

Evaluating and meeting a patient’s spiritual needs is a key component of improved healthcare outcomes. Addressing spiritual needs/distress of patients can improve patient’s perceptions of quality of life, assist in the development of effective coping strategies, reduce rates of depression in elderly inpatients [3] and eliminate patient’s feelings of loneliness and anxiety [4].

According to the OTPF, occupational therapists can address spiritual needs. However, spirituality is likely not often included OT practice due in part to the lack of common spiritual language, reported unawareness of OT’s role in spirituality in practice, lack of perceived therapist’s skills to have spiritual conversations owing to distress, and alleged inability to receive payment for spirituality treatments [5].

Practicing occupational therapists also report an educational barrier to the inclusion of spirituality in practice [6-8]. Clinicians report that their ELOT education did not train them to evaluate and treat spiritual needs of patients [6-8]. Likewise, ELOT students report low confidence in the ELOT curriculum to prepare them for addressing spirituality needs [9,10]. A spirituality unit of instruction in an ELOT course may serve as a solution to the educational barriers of needed conversational skills, unfamiliarity of OT’s spiritual role, and common spiritual language. Therefore, the premise of this project was that students would benefit from participation and engagement in a spirituality unit of instruction to ultimately enhance patient recovery outcomes in the future and essentially lessen the educational barrier of addressing spirituality in practice.

This quality improvement project was the development of guidelines for inclusion of a spirituality unit of instruction into an ELOT course. The guidelines and the unit of instruction itself were directed by adult learning theories including Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory, Roger’s Experiential Learning Theory, and Mezirow’s Transformative Learning, and Subject-Centered Integrative Learning Model (SCIL-OT) [11]. As a result of participating and engaging in this unit of instruction, it was expected that students will gain knowledge, skills, awareness, and confidence necessary to address spirituality as general practitioners in the future.

Aim(s)

The first aim of this quality improvement project was to develop an evidence-based online spirituality unit of instruction to increase confidence, self-awareness, and knowledge of ELOT students. The second aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of the unit of instruction using quantitative and qualitative pre/post outcome measures. The third aim was to develop faculty approved guidelines for the incorporation of a spirituality unit of instruction into ELOT curriculum.

Hypotheses

1. I hypothesized that if ELOT students engage in an online unit of instruction for addressing spirituality in stroke survivors, then the level of confidence to address spiritual needs, self- awareness of bias, and knowledge of evidence-based evaluation/ intervention will significantly increase.

2. I hypothesized that ELOT students who engage in an online unit of instruction for addressing spirituality in stroke survivors, will report higher levels of perceived confidence, self-awareness, and knowledge when compared to ELOT who did not engage in the unit of instruction.

3. I hypothesized that the developed guidelines for the inclusion of the spirituality unit of instruction will be approved by three out of five various instructors and an Accreditation of Occupational Therapy Education (ACOTE) board member for use in ELOT curriculum.

Background and Significance:

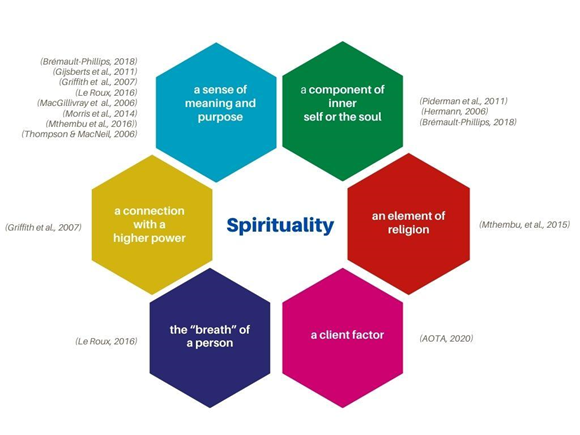

There is no common language to describe spirituality of patients in the healthcare literature. The World Health Organization 2002’s definition of holistic healthcare integrates physical, mental, social, and spiritual dimensions of health [9]. To meet the World Health Organization’s definition of holistic care, the patient’s spiritual needs/distress must be evaluated and treated for enhanced patient outcomes. Even despite the increased attention to spirituality through holistic care, there continues to be a lack of a universal definition for spirituality, spiritual needs/distress/wellbeing in health care. Definitions of spirituality in the literature range from creating meaning and purpose [6-8,10,12-15] to being a component of inner self or the soul [3,4,12] to a connection with a higher power [14]. In Greek and Latin tradition, spirituality refers to the vital spirit or “breath” of a person [15]. The OTPF defines spirituality as “a deep experience of meaning brought about by engaging in occupations that involve the enacting of personal values and beliefs, reflection, and intention within a supportive contextual environment” [1]. The OTPF further describes spirituality as a client factor, residing in the person, listed along with values, beliefs, body functions, and body structures. The patient’s values, beliefs, and spirituality inspire the patient to engage in occupations; thusly, delivering meaning to life [1].

Important aspects of spirituality are the concepts of spiritual agency and spiritual need. The term “spiritual agency” can relate to a patient’s freedom of choice to participate in spiritual occupation or activities of the spirit to address a variety of needs [16]. A spiritual need can be defined as something required by an individual to find purpose and meaning in life such as love, hope, and preeminence beyond self [17]. For example, a stroke survivor may have spiritual needs associated with role loss, damaged occupational identity, purpose uncertainty, inadequate coping strategies, and social/ transcendent disconnection [18-20]. Spiritual needs are at the highest point of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs through self-actualization moving through matter, body, mind, soul, and spirit [9]. The Spiritual Needs Model is based on five spiritual needs of hospitalized elderly patients including the need (1) for life balance, (2) for connection, (3) for values acknowledgement, (4) to maintain control, and (5) to maintain identity [21]. The greater a spiritual need, the greater the level of spiritual distress or disturbance in spiritual well-being [21].

Other important aspects of spirituality are the concepts of spiritual distress and well-being. Spiritual distress is a disruption in a person’s values and beliefs which add meaning to life and is associated with increased depression and desire to hasten death in end-of- life patients [22]. Well-being in general is comprised of positive emotions, relationships, achievement, and meaning, hence its close connection with spirituality [15]. Spiritual well-being has vertical and horizontal planes associated with relationship to God/higher power and awareness of life’s meaning and fulfillment [17]. Low spiritual well-being has been associated with higher mortality rate, desire for accelerated death, hopelessness, and depression [17].

Addressing the spiritual needs/distress of patients in inpatient hospital settings is shown to improve patient health outcomes. In other words, studies show that the absence of spiritual need/distress improved health outcomes, quality of life perceptions, effective coping strategies, while reducing depression, and elderly suicide rates [3]. There is a growing body of evidence to support spirituality as an aspect of well-being and recovery [12] which are two key components of healthcare outcomes. According to a 2014 study, there is a relationship between spirituality and client-centered practice, emotional well-being, therapeutic relationships, and motivation [8]. Self-identity is dependent upon what is considered meaningful and can be adjusted socially, psychologically, and spiritually [14]. Practicing spirituality helped people experiencing major life event to strongly endure them and remain calm [23]. Those who engage in spiritual and religious practices are more optimistic, happy, and satisfied with life [12]. According to a 2005 meta-analysis, in rehabilitation programs that considered spirituality, patients demonstrated improved patient self-confidence, problem-solving, and decision making [24].

One reason the concepts of spirituality, spiritual needs, distress, and well-being may not as readily be addressed in health care is potentially because of healthcare provider biases [25]. Moreover, a misunderstanding of the roles of healthcare professionals such as occupational therapists and chaplains can unintendedly reduce access to spiritual care. Some healthcare providers view chaplains as “sellers of religion” who help to sort out the details of faith [25]. However, hospital chaplains do more than sort out details of faith. Hospital chaplains address the psychosocial, existential, and spiritual needs of patients through active, empathetic listening and utilize spiritual assessments to identify those needs [25].

Although, patient spiritual needs are primarily addressed by hospital chaplains, occupational therapists also can play vital role in addressing patient spiritual needs. Occupational therapists do not provide spiritual advising; however, they can work with all types of patients with varying degrees of divine beliefs (from present to absent) and can address spiritual needs through supporting and identifying health-outcome-improving spiritual occupations [1]. Spiritual occupations may include but are not limited to prayer, meditation, bible reading, singing, reflection, yoga, and interpretive dance. Spiritual activities may include exercising, meditating, going to church, listening to gospel music, sleeping, eating healthy, and being in nature [9]. In some instances, ordinary occupations can become spiritual such as gardening because it connects the individual to nature [16]. Occupational therapists also have a role of addressing accessibility to sacred places for spiritual participation [16]. The primary goal of OT is to empower individuals to participate in occupations that are valuable and meaningful to them by addressing their needs including the spiritual needs such as occupational identify, well-being, and quality of life [23].

Currently, occupational therapists are not commonly addressing patient spiritual needs in practice [26] due at least in part to limited ELOT education on the topic of spirituality. Clinicians feel their ELOT education did not prepare them to evaluate and treat spirituality in patients [6-8]. There is a gap between spiritual theory and practice in occupational therapy [8,10]. Student confidence in OT education curricula and experience to address spirituality is low [9,10]. Unfortunately, despite high levels of evidence supporting spirituality for recovery, healthcare education is lacking [8] Yet, there are no Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (ACOTE) standards specifically dedicated to spirituality [27]. Some have suggested that spirituality is a taboo topic that speaking of it in institutional settings is unprecedented [6]. In many ELOT education programs, spiritual occupations may be implied within any discussion of intervention or strategy [11]. If full courses are devoted to the client factors of body function and body structures, then why does spirituality not receive the same level of importance in ELOT curricula?

Another reason spirituality, spiritual needs, distress, and well-being are not as readily addressed by occupational therapists in inpatients is because these concepts are not easily fit into the traditional biomedical model. Body structure and function client factors can be categorized in the traditional healthcare biomedical model, whereas values, beliefs, and spirituality client factors fit in a more psychosocial model. The need to find purpose and meaning is just as important as addressing physical needs [14]. Occupational therapists seek to address not only the physical but the spiritual. Unfortunately, the term “therapy” is defined so broadly, that the objective of remediating tangible problems may overlook the spiritual [6]. Occupational therapy practice offers a psychosocial model entitled the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and Engagement (CMOP-E), in which meaningful occupations develop from the collaboration of spirituality and environment and spirituality at the core of the person [14,16]. Spirituality can influence and be influenced by occupational performance and engagement [1].

The addition of a full unit of instruction into an ELOT course may enable ELOT students to connect spirituality as a client factor with occupational performance and engagement. The importance of the relationship between occupations and treatment is suggested by the Subject-Centered Integrative Learning Model (SCIL-OT). This model can be used to underscore the importance of spiritual occupations as interventions for stroke survivors. The SCIL-OT is a conceptual model that outlines the theoretical foundations, elements, and principles of occupation-centered education and “offers a roadmap for curriculum and instructional design that seeks to place the concept of occupation at the center of all aspects of education” [11]. The opportunity to incorporate spirituality in ELOT curriculum is vast and underutilized. Shockingly, there is an immense drought in the literature of clearly defined guidelines and objectives for instructing OT students in the role of addressing spiritual needs, spiritual distress, and spiritual wellbeing through appropriate spiritual assessments and spiritual occupations as interventions [6,8-10].

ELOT students can benefit from learning about the link between the patient’s spirituality and patient outcomes. A spirituality unit of instruction may offer a solution to this avoidable educational problem in OT practice. If a spirituality course precedes a physical dysfunction course, the former will influence the view of the latter [6]. Students demonstrated clarity related to definitions of spirituality and spiritual care as well as how to respond empathetically to spiritual pain when addressed in OT courses [10]. Students benefit from exercises to express their own spirituality (such as journals or music) to increase confidence and awareness of potential biases that need to be addressed before addressing spiritual needs in others [6,10]. So, why are there no proposed guidelines in the literature for inclusion of spirituality unit of instruction in ELOT education? The purpose of this project was to satiate this deficiency via the development of an online unit of instruction for addressing spirituality in stroke survivors; thusly, addressing barriers to practice related to confidence, self-bias awareness, and knowledge.

Approach/Methods

Design

This quality improvement project investigated the effect of an educational module using nonrandomized, pretest/posttest, educational-comparator design.

Participants

Aims 1 & 2: Students

Fifty ELOT doctoral students expected to graduate in 2023 from a public university in the southern United States, participated in the unit of instruction as the intervention group (pre-unit/post-unit group). The previous cohort of ELOT students (class of 2022) who did not attend a unit of instruction on addressing spirituality served as the educational comparator (no-unit group). For this quality improvement project, students from other health profession disciplines were not included.

Aim 3: Instructors

Five ELOT instructors were selected to review and provide feedback on the guidelines/unit of instruction. To include a range of ELOT programs, instructors were selected that teach in doctorate and master’s level programs. To include a range of clinical and academic experience, instructors were selected to provide feedback on the guidelines with less than one year to almost two decades of experience which innately includes a range of academic titles from instructor all the way up to professor. Two of the instructors who were selected were new to academia and are up to date with new evidence regarding teaching strategies along with the challenges of teaching newer material. One instructor was selected to participate who had a new doctorate degree in education to provide in-depth insight into successful teaching strategies and evidential support. One instructor was selected who was a member of the ACOTE accreditation board to review the unit-of-instruction’s ability to meet current ACOTE standards.

Content Mentors

Two hospital chaplains, from a hospital neighboring the university, were included in the development of the unit-of-instruction content who were agreeable to openly discussing their role of addressing spiritual needs of patients and their perspective of OT’s role.

Development of Educational Tools (guidelines and unit of instruction)

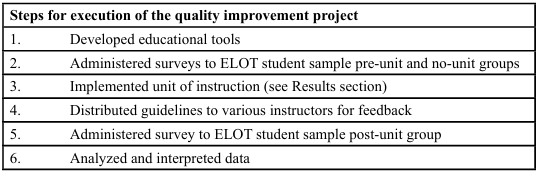

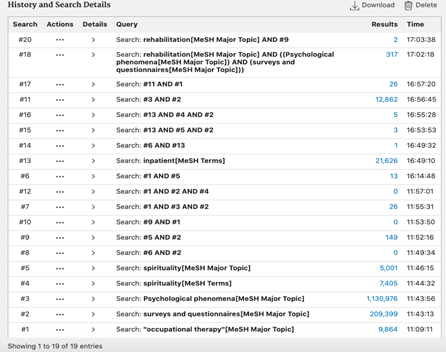

An online, synchronous “Stroke of Spirituality” unit of instruction, developed by Roblin Fenters, OTR/L, was integrated into the Dr. Michelle Woodbury’s OTD 819: Neurorehabilitation I course at the university. Topics included in the unit of instruction were selected based on limited class time, interview with the hospital chaplains, and the aforementioned educational barriers identified by the initial literature search. To guide the literature search, a research question was developed using the Problem-Intervention-Comparative- Outcome (PICO) method. The question “During the acute care stage of hospitalization is assessing and addressing spirituality compared to not addressing spirituality improve overall quality of life and motivation” was used to guide the literature search. The university’s online library was used to search the PubMed database for articles to support the rationale, background, and content of the unit of instruction. The National Center for Biotechnology Information website was used to create a list of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms of vocabulary used for indexing articles in PubMed. The following combinations of MeSH Major Topics and Terms yielded articles that were read and summarized in a searchable bibliography: inpatient, surveys and questionnaires, spiritually, rehabilitation, occupational therapy, psychological phenomena, activities of daily living, human activities, spiritual therapies, hospitalization, humanities, inpatients/ psychology, stroke rehabilitation, and education.

Five searches of MeSH terms like the one in Figure 2 were conducted over the course of two weeks. The resulting articles from the MeSH term searches were read, summarized, and written in a Word document using thematic topics of definitions, theoretical basis, relationships between spirituality and OT, barriers to addressing spirituality, potential solutions, appropriate OT spirituality assessments, interventions, and ideas for future study.

The idea of creating this unit of instruction was inspired by a 2020 article entitled “Sense of Connection: Addressing Spirituality in Occupational Therapy Practice” by Marissa Marchioni and Rebecca Cunningham [28]. Once the idea of creating a unit of instruction was affirmed by content mentors, the literature search bibliography document was used to identify the three main educational barriers (confidence, self-awareness, and knowledge) of including spirituality in OT practice. Activities and lecture content was selected based on its relationships to those main educational barriers with supporting evidence from the bibliography document using Microsoft Word’s “find” feature.

Autobiographies were also included in the creation of the unit of instruction. To create a list stroke survivor spiritual needs and appropriate occupational interventions, four stroke survivor autobiographies were read and summarized on the same bibliography document.

Using a lesson plan template from the Teaching Experience course in university’s post professional OT doctoral program, a table was developed to list educational activities, approximate times to complete those activities (to remain within the three hour time limit of the class) and evidential support for those teaching methods. The unit of instruction incorporates an advanced instructional design to facilitate critical thinking discussions, active learning group activities, and includes problem-based/experiential learning with time for self- reflection and sharing. These adult learning methods were selected based on successful evidential improvement of student understanding as discussed in the book entitled McKeachie’s Teaching Tips Strategies, Research, and Theory for College and University Teachers Fourteenth Edition [29]. See Unit of Instruction Implementation section for specific topic selection and justification. To facilitate learning, transitions between topics, present figures/examples, and instructions for group activities, Microsoft PowerPoint and individual handouts were created using Microsoft Word and posted on the Harbor page.

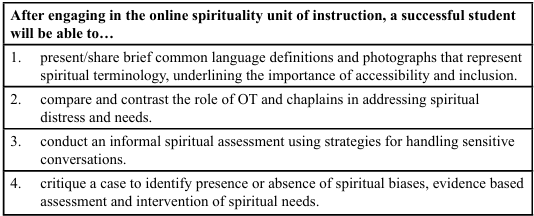

The following unit of instruction objectives were selected to ensure that the unit of instruction helps students meet the course’s objectives and ACOTE standards. Participation in activities/assignments of this unit of instruction, meet in whole or in part the neurorehabilitation course learning objectives and ACOTE standards B.2.2, B.3.3, B.3.4, B.4.4, and B.7.3 [27]. Using adult learning principles, the unit of instruction addressed cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains of learning. Cognitively, the foundations for future courses were laid through the provision of clear definitions of occupational therapy (OT) terminology and the working relationships for application in real-life cases. Affectively, current personal spiritual beliefs will be self-examined through identifying biases. Lastly, the psychomotor domain was used by demonstrating administration of a theoretically supported non-standardized assessment measure.

Specifically, these unit of instruction learning objectives were created to address the educational barriers of the inclusion of spirituality in OT practice. Learning objective one was created to facilitate a unified definition of spirituality for OT students serving as a potential solution to the barrier of a lack of consensus on spiritual terminology in the literature. Figure 1: Diagram of six definitions of spirituality was used to illustrate this lack of common spiritual language. Learning objective two was created to facilitate students’ knowledge regarding the differences in roles of OT and chaplains for addressing spiritual distress in patients to ultimately serve as a potential solution to the educational barrier that may impact its inclusion in OT practice [25]. Specifically for unit-of-instruction learning objective number two, two hospital chaplains agreed to participate in a recorded interview via zoom for their perspective on healthcare providers’ role of addressing spiritual needs. Verbal consent to record the interview was obtained prior to recording. The apple iMovie application was used to edit and condense the video into an appropriate length and for enhanced educational accessibility [29]. Lastly, the video was included in the PowerPoint slides and onto the university’s learning management system. Learning objective three was created to facilitate the students’ confidence and awareness of skills needed to conduct difficult spiritual conversations during client evaluations to potentially address the education barrier of lack of ELOT preparation [26,7,8]. The content of the lecture addressing objective three was developed from a combination the author’s clinical experience and adapted tips from a video entitled “EntreLeadership Takeaways: How to Navigate Crucial Conversations with Joseph Grenny & Ken Coleman.” The fourth learning objective was created so that students can demonstrate understanding related to the prior objectives. The case-study problems were inspired by real patients in the author’s clinical practice. Only four learning objectives were used due to the length of the unit of instruction (approximately three hours).

Outcome Measures

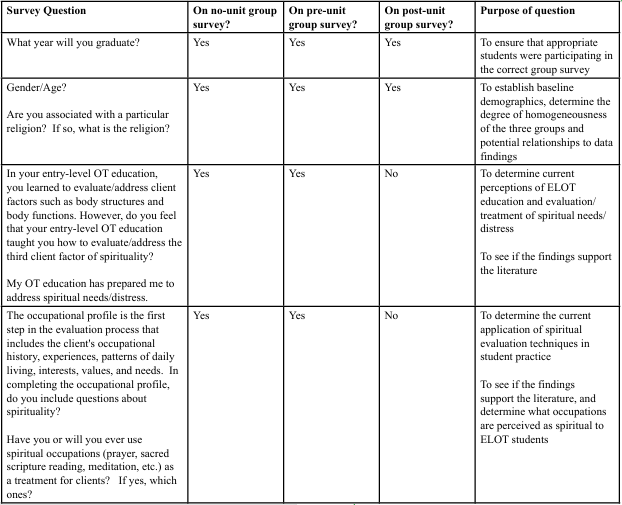

This study included mixed methods of prospective data in form of quantitative surveys including Likert scales and qualitative short answer survey questions. Students indicated their level of agreement with statements about confidence, knowledge, and self-awareness. See Table 3: Survey Questions for details.

Administration of Surveys

The three surveys were administered through RedCap, a secure platform for data collection, as a hyperlink in an email from the course instructor. The university’s class of 2023 ELOT doctoral students were provided a survey before and after participation in the unit of instruction on February 18, 2021 and February 19, 2021, respectively. The pre-unit survey was closed just prior to implementing the unit of instruction on February 19, 2021 and post-unit survey was closed on February 25, 2021. The university’s class of 2022 ELOT doctoral students were provided a survey for educational comparison. The link to the no-unit RedCap survey was sent out via email from the course instructor on February 23, 2021 through February 25, 2021.

Instructor Guideline Distribution

The guidelines were emailed via a word attachment to five instructors asking for (1) approval or disapproval and (2) feedback. Three of the instructors required follow-up reminder emails. The instructors emailed an attachment back to the author with track changes and review comments as feedback. The author of the unit of instruction and guidelines recorded the approvals on an excel spreadsheet and summarized the feedback via reoccurring themes. No changes were made to the original guidelines.

Data Analysis

Demographic data was summarized using frequencies, ranges, and percentages for comparison between groups.

To determine changes and/or difference between group responses to Likert scale questions, data were downloaded from Redcap into a Microsoft Excel workbook. Each Likert scale question was listed with pre-unit, post-unit, and no-unit answers to create a data array. Then the bins array was created in a table using numbers 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 correlating to strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly agree respectively. Lastly, using the Excel Frequency Array Formula, frequency of answers was determined and divided by number in the sample times one hundred for the percentage. Percentages allowed for comparisons to be made between groups. Data from the frequency percentage tables were represented via bar graphs in Excel. To meet the aims and hypothesizes of this project, data were compared (1) between pre-unit and post-unit for increases and (2) between pre unit and no-unit for biases and (3) between post-unit and no-unit for unit effectiveness at address the educational barrier to inclusion of spirituality in OT practice.

To determine common themes within the student and the instructor qualitative feedback, answers were copied into Microsoft Word. Repeated words were highlighted in matching colors to determine themes. The themes were then listed with quotes in each category.

Results

Implementation of the Unit of Instruction

For privacy and safety of instructor and students, the unit of instruction was delivered via Zoom, a video conference software. To provide a secure, safe online learning environment, the Zoom platform provides security features such as meeting encryption, expel participations, lock meetings, and passcodes [30]. Students were provided handouts, (Spiritual Terminology, Venn Diagram, Fill-in-the-blank Notes, and Role-Play Checklist) via the university’s learning management system.

The unit-of-instruction was taught via Zoom on February 19, 2021. The following outlines the chronological order of learning activities:

1. During the first five minutes of the unit of instruction, the instructor introduced herself to help students reduce anxieties and find commonalities between peers [29].

2. Next, for approximately ten minutes, the instructor explained why the content of the unit of instruction matters since relating content with real life can increase student expectation of excitement-inducing course [29].

3. Activity 1: For the first group activity, students used their favorite social media outlet to identify photographs that portray spiritual terminology that was provided via a required handout on Harbor. Use of social media in the classroom can develop life-long learners even outside the classroom because of its intrinsic motivation and self-directed nature [31]. Actively using the spiritual terminology allowed the students to demonstrate understanding of the concepts during spontaneous instructor entry into Zoom breakout rooms, a method of online group work.

4. Chaplains: After students completed the first activity, the instructor played a recorded interview with two MUSC Chaplains and an OT to help explain the differences between the roles for addressing spiritual needs, spiritual distress, and spiritual wellbeing. The students completed a comparing/ contrasting Venn Diagram, provided via Harbor, of the role OTs and chaplains while watching the video. Providing notes can guide attention to key concepts during media presentations [29].

5. Short break: Students were provided with a brief break for regenerating attention and focus.

6. Activity 2: Next, the students engaged in the second activity of self-reflection while listening to spiritually biased statements. Students kept a record of the number of statements they have personal experience with for reflection which was not discussed with peers. The goal of this activity was to facilitate reflection of students’ currently held assumptions about the world and facilitate active reflection for transforming the mind to enhance OT as a profession into the future.

7. Lecture: Next, the instructor explained spiritual OT models while student completed “fill-in-the-blank” notes provided via Harbor. Lecture content was supplemented via Microsoft PowerPoint to highlight key concepts. Lectures can be effective if only key concepts and principles are highlighted instead of full details [29].

8. Activity 3: For approximately thirty minutes, students engaged in the third activity of role-playing the use of informal spiritual assessment supported by the spiritual occupational therapy model. Role-playing allows students to be active learners instead of passive observers [29]. Students evaluated peers to provide feedback using a checklist provided via Harbor. Peer assessment (using a checklist as a guide) allows students to develop the skills of self-assessment and improve performance [29]. Checklists can clarify expectations, so students have a clear understanding of the steps they are to perform during the activity [32].

9. Short break: The students were provided with another cognitive break.

10. Activity 4: After the instructor explained spiritual interventions and accessibility, the students used their cellphones to search Pinterest, a creative image driven social media platform, to identify potential spiritual occupations that patients could participate in while in the hospital. The use of personal smart phones brings current culture into the classroom.

11. Conclusion: Lastly, the course concluded with two case- studies in which students answer “what are the patient’s spiritual needs?” and “what might the treatment look like?” to demonstrate understanding at the highest level of Bloom’s Taxonomy. The case method is a type of experiential learning that helps student facilitate problem solving, application of relevant course content, and inspection of other resources [29].

The guidelines for inclusion of spirituality in an ELOT neurorehabilitation course were developed using Microsoft Word. The guidelines include descriptions regarding the course/unit of instruction titles, course/unit of instruction instructors, course/ unit of instruction length, and course/unit of instruction dates. The guidelines also detail the course/unit learning objectives with included relation to ACOTE standards, required unit handouts, unit lesson plans including topics, approximate time to complete, learning activities, and teaching evidential support. The guidelines have PowerPoint slides to facilitate the lectures and activities. The instructor PowerPoint speaker notes are included in the guidelines in outline format for ease of use during the synchronous unit of instruction. Lastly, the guidelines present sample evaluation methods with evidential support.

Student Demographics & Quantitative Data

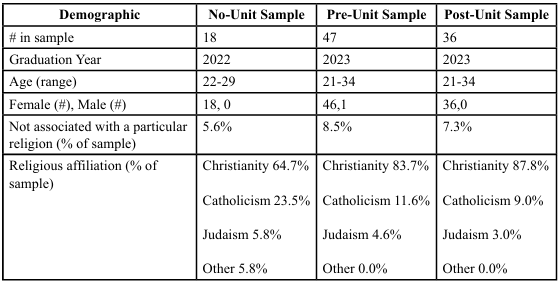

Fifty class of 2023 ELOT students participated in the three-hour unit of instruction. Forty-seven class of 2023 (pre-unit) ELOT students completed the pre-unit of instruction survey. Thirty-six class of 2023 (post-unit) ELOT students completed the post-unit of instruction survey. Eighteen class of 2022 (no-unit group) ELOT students did not participate in the unit of instruction but completed the no-unit group survey. The no-unit group survey and post-unit survey were completed by all females and only one male completed the pre-unit survey. Six percent of the class of 2022 ELOT students and seven to eight percent of the class of 2023 ELOT students report no affiliation with a particular religion. Most of the class of 2022 ELOT students (64%) and class of 2023 ELOT students (83-87%) are associated with the Christian religion. Six percent or less of class of 2022 and 2023 ELOT students are associated with Judaism.

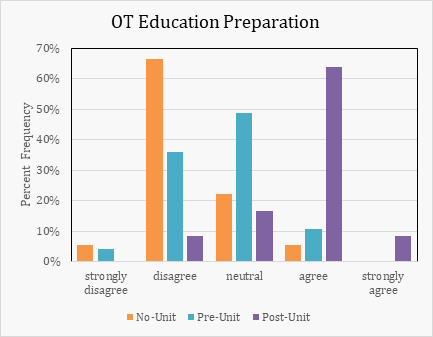

Six percent of the no-unit group and eleven of pre-unit ELOT students report agreement with the statement “My OT education has prepared me to address spiritual needs/distress.” After participating in the unit of instruction, seventy-two percent of the post-unit ELOT students report agreement with the aforementioned statement.

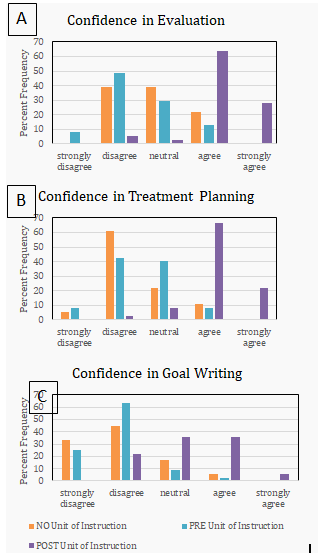

Twenty-two of the no-unit group ELOT students and thirteen percent of pre-unit ELOT students reported agreement with the statement “I feel confident in how to include spirituality in my evaluation of clients.” After the unit of instruction, ninety-two percent post-unit ELOT students report agreement with the statement. Eleven percent of the no-unit group ELOT students and nine percent of pre-unit students reported agreement with the statement “I feel confident in including spiritual occupations in my treatment planning.” After the unit of instruction, eighty-nine percent post-unit ELOT students report agreement with the statement. Six percent of the no-unit group ELOT students and two percent of pre-unit ELOT students reported agreement with the statement “I feel confident in how to write goals related to spirituality.” After the unit of instruction, forty-two percent post-unit ELOT students report agreement with the statement.

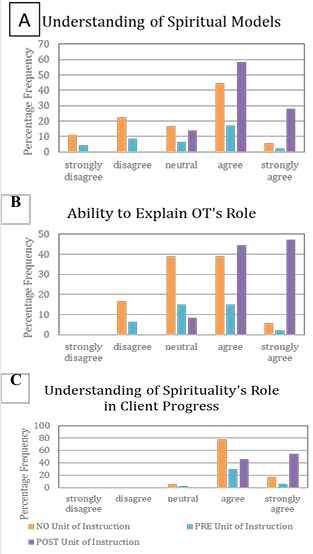

Fifty percent of the no-unit group ELOT students and nineteen percent of pre-unit ELOT students reported agreement with the statement “I understand one or more occupational therapy models that include spirituality.” After the unit of instruction, eighty-six percent post-unit ELOT students report agreement with the statement. Forty- five percent of the no-unit group ELOT students and six percent of pre-unit students reported agreement with the statement “I can explain what role occupational therapy can have in addressing or supporting spirituality.” After the unit of instruction, ninety-one percent post-unit ELOT students report agreement with the statement. Ninety-five percent of the no-unit group ELOT students and thirty- six percent of pre-unit ELOT students reported agreement with the statement “I understand the role spirituality can have in supporting client progress.” After the unit of instruction, one-hundred percent post-unit ELOT students report agreement with the statement.

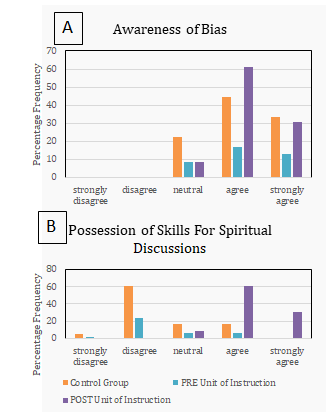

Seventy-seven percent of the no-unit group ELOT students and thirty percent of pre-unit ELOT students reported agreement with the statement “I am aware of my personal biases related to spirituality.” After the unit of instruction, ninety-two post-unit ELOT students report agreement with the statement. Seventeen percent of the no-unit group ELOT students and six percent of pre-unit students reported agreement with the statement “I possess the skills needed to have difficult spirituality discussions.” After the unit of instruction, ninety-two percent post-unit ELOT students report agreement with the statement.

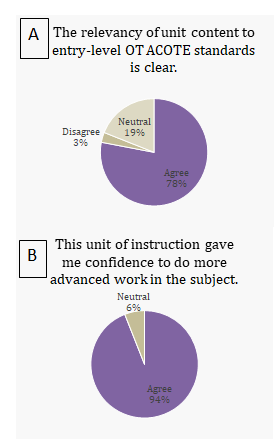

Seventy-eight percent of post-unit ELOT students report agreement with the statement, “the relevancy of unit content to entry-level OT ACOTE standards is clear.” Three percent disagreed with the statement. Ninety-four percent of the post-unit ELOT students agree with the statement “this unit of instruction gave me confidence to do more advanced work in the subject.”

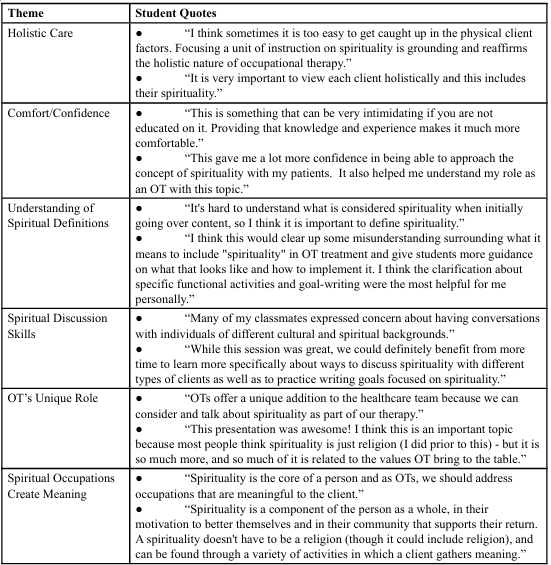

Table 5: ELOT Student Reasoning for Inclusion of a Spirituality Unit of Instruction to Entry-Level Curriculum

Post-unit ELOT student survey participants answered the question “should a spirituality unit of instruction be added to entry-level OT curriculum?” Six thematic reasons to include a spirituality unit of instruction include to prepare students for holistic care as therapists, increase comfort/confidence with addressing patient spiritual needs, increase understanding of spiritual definitions, develop discussion skills, underline a unique role of OT and emphasize how spiritual occupations create meaning.

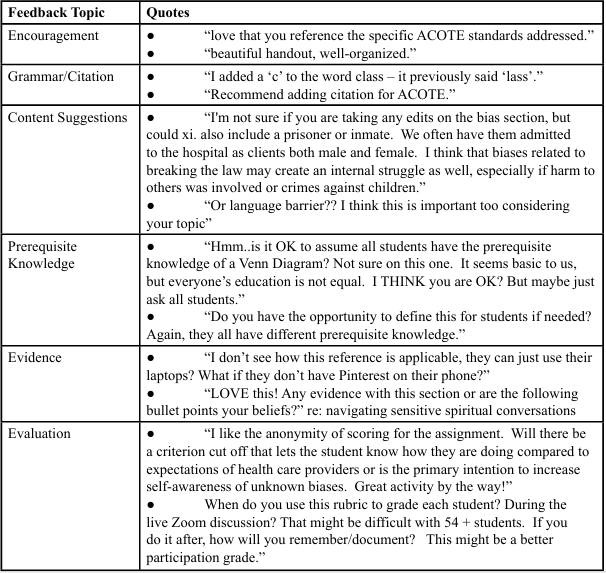

Five ELOT instructors participated in reviewing guidelines for inclusion of spirituality into ELOT curriculum. The instructors have nine to thirty-three years of clinical experience and six months to nineteen years of academic experience. Four instructors teach doctorate ELOT students and two instructors teach master’s ELOT students. Academic titles include instructor, adjunct professor, assistant professor, associate professor, and professor. One instructor has a doctorate degree in education, and one is an ACOTE accreditation board member. All five instructors approved the guidelines via email. Instructor feedback was in the areas of grammar, content, prerequisite knowledge, evidence, and evaluation with a plethora of encouragement.

Discussion

To help meet the triple aim of healthcare, patient outcomes can improve through addressing spiritual needs/distress of patients in inpatient hospital settings. However, patients’ spiritual needs/distress are not commonly, currently being addressed by OTs due in part to educational barriers. This study sought to address the educational barriers of perceived confidence, self-awareness, and knowledge hindering the incorporation of spirituality in OT practice. develop guidelines for the inclusion of a spirituality unit of instruction in an ELOT neurorehabilitation course. The results demonstrate students’ and increased in perceived level of confidence, self-awareness, and knowledge for addressing spirituality in OT practice when comparing survey data before and after participation in the unit-of-instruction.

Preparedness

This study found that only six percent of the no-unit group and eleven percent of the pre-unit ELOT students felt their entry-level OT education, to the present point in their academic programs, had prepared them for addressing spiritual needs/distress of clients. These data are consistent with the findings of a 2014 study indicating that approximately two-thirds of clinicians surveyed felt their formal ELOT education did not prepare them to evaluate and treat spirituality in patients [8]. Excitingly, after a three-hour unit presentation, participants’ perceived level of preparedness increased from eleven percent to seventy-two percent. These data indicate that even after a short unit of instruction, students’ perceptions of preparedness can greatly increase. These findings also suggest the need for a spirituality unit-of-instruction, not even a full course, as a potential solution for the educational barrier to addressing spirituality in OT practice.

Confidence

Studies show that students’ confidence in their OT education curricula to address spirituality is low [9,10] but confidence can be increased when students are provided with opportunities to exercise and express their own spirituality [6,10]. The results of this quality improvement project are consistent with those findings. The data show that the sample increased their perceived confidence in evaluating (13% to 92%), treatment planning, (nine percent to 89%) and goal writing (two percent to 42%) for spiritual needs of clients by participants of the spirituality unit of instruction. The percentage increase in confidence in goal writing may have been limited as spiritual goal writing was not explicitly covered in this unit. Students were provided with opportunities to express their own spirituality through photographs and intimate discussions with peers. The no-unit group did not get to participate in this confidence building activities, revealing lower confidence than the post-unit in evaluation (22%), treatment planning (11%), and goal writing (six percent). A 2012 study found that addressing spirituality for those with psychological pathology can be a source of distress [16], and these findings suggest the spirituality unit-of-instruction is a potential solution for building confidence to dispel clinician distress in the future.

Knowledge

This study and another study conducted in 2016 found that students demonstrate clarity related to spiritual terminology when addressed in OT courses [10]. This study specifically found that students’ understanding of spiritual models (19% to 86%), OT’s role in addressing spiritual needs (six percent to 91%), and the role of spirituality in client’s progress (36% to 100%) increased after participating in the unit of instruction. The no-unit comparator group demonstrated low spiritual knowledge of models and OT’s role in addressing spirituality (five percent and 45%, respectively) but demonstrated high knowledge of spirituality's role in supporting client progress (95%). The discrepancies in no-unit comparator group spiritual knowledge may be related to the additional classes that they have participated in that the post-unit group has not and the general unprecedented discussion of the topic in institutional settings [6]. One student reported how a spirituality unit “can clear up misunderstandings of what it means to include ‘spirituality’ in OT treatment” which supports a spirituality unit of instruction as a solution to the inconsistent/unclear spiritual definitions.

Self-Awareness

Healthcare provider bias can limit patient access to spiritual care due to misunderstandings in the role of the chaplain services [25]. If students are made aware of biases, they are more likely to refer patients to spiritual care. Also, Griffith and colleagues found that people do not experience spirituality equally [14]. This study supports those findings in that the students’ perceived awareness of spiritual bias increased from 30% to 92% after participating in the unit of instruction which is higher than the no-unit group’s perceived awareness of spiritual bias (77%). In the healthcare setting, disagreements between healthcare providers and between provider and patient is a result of religious and spiritual diversity which sometimes manifests as a conflict within the individual healthcare provider themselves [33]. All the students included in this study were from the same institution and the no-unit group’s self-awareness is potentially high for this sample due to the institution’s mission to increase diversity and inclusion. If students at MUSC are educated on spiritual competency included within cultural competency then awareness of potential stereotypes, stigmas, and biases are forefront in their minds. As mentioned previously, spiritual biases can lead to healthcare exclusion and religious diversity can lead to a variety of valued traditional occupations that are not being offered in inpatient settings by occupational therapists. It is unknown that if the sample included students from other institutions or even a more diverse religious background, that this self-awareness would be as high prior to the unit of instruction.

Difficulty addressing spirituality in therapy is negatively correlated with clarity of occupational therapy’s role in spiritual wellbeing [8]. Only 17% of the no-unit group report that they are aware that they possess the skills needed to navigate difficult spiritual discussions with patients, and 92% of the post-unit students report the awareness of said possession of skills. The combined low knowledge of OT’s role of addressing spirituality (45%) and low self-awareness of possession of skills needed to discuss spiritual matters further supports the findings of Morris and colleagues in their 2014 study. Therefore, the unit of instruction can serve as a potential solution to reduced patient access to spiritual care because students are more likely to engage in spiritual discussions with patients possessing the skills needed to navigate difficult conversations. However, awareness of spiritual bias does not always translate to active attempts to provide unbiased care. This study did not investigate this transference of awareness to action. The combined low confidence, low self- awareness of skills needed to have spiritual conversations and high self-awareness of bias of the no-unit group may negatively impact patient care since an OT’s discomfort with discussing spiritually may stem from a negative personal experience [6].

Student Unit Feedback

There are no ACOTE standards directly related to spirituality in OT practice despite its evidential relationship with occupations and meaning [6]. Instructors must always be aware of ACOTE standards when developing course content, to evaluating performance skills, to implementing projects. The student’s focus is more likely on the learning objectives of the course that meet those standards and may not be as focused on the ACOTE standards themselves. Despite this shift of focus 78% of post-unit ELOT students report agreement that the unit is relevant to ACOTE standards. Ninety-four percent of students report confidence in pursuing further study in spirituality. This confidence is vital for the advancement of OT in spirituality as there is currently a lack of occupational spiritual formal assessments which makes spiritual distress/needs difficult to treat.

Instructor Unit Feedback

There is a lack of evidence identifying the relationship between spirituality as a client factor and its impact on occupational performance [8]. Lack of evidence in this unit of instruction was also a theme of feedback from instructors. Despite this need for more evidence, all five instructors from various institutions and including an ACOTE board member approved the guidelines for the unit of instruction. Specifically, one instructor commented on the interest in the “navigating sensitive spiritual conversations section” and wanted to know what evidence supports this strategy or if it was an opinion of the unit’s author. This spiritual conversation section is crucial to the increase in perceived possession of skills to have difficult discussions with patients and increase in confidence for evaluation of spiritual needs/distress. Therefore, in revisions of the guidelines and unit of instruction, it will be made explicitly clear that the content of that section is a collaboration of the unit’s author’s clinical experience and adapted from tips provided in a video entitled “EntreLeadership Takeaways: How to Navigate Crucial Conversations with Joseph Grenny & Ken Coleman.” The addition of this source detail could be next steps in increasing the volume of evidence supporting inclusion of a spirituality unit of instruction in ELOT curriculum.

Limitations

Two of the instructors are currently in the same post-professional doctoral cohort as the author of this quality improvement project, and the remaining three instructors have taught the author of this quality improvement project; therefore, the presence of bias is unknown. The no-unit group was a small sample from the same institution.

Conclusion

Without these educational tools (guidelines and unit of instruction), there continues to be an immense drought in the literature of clearly defined guidelines and objectives for instructing OT students in the role of addressing spiritual needs /distress/wellbeing through appropriate spiritual assessments and spiritual occupations as interventions [6,8-10]. Using The SCIL-OT conceptual model, the guidelines outline the theoretical foundations, elements, and principles of occupation-centered methods for assessing, addressing, and treating spiritual needs and distress in patients [11]. The unit of instruction kept occupation at the forefront for addressing spiritual needs/distress through spiritual occupations [11]. MUSC’s ELOT students benefited from a spirituality unit of instruction, addressing an educational barrier to inclusion of spirituality in OT practice. The developed educational tools (guidelines and unit of instruction) suggests common language to describe spirituality in OT practice and provides a solution to reported low entry-level preparedness and perceived confidence, knowledge, and self-awareness to evaluate and treat spiritual needs [6-8] as evidenced by increasing student perceptions through entry-level program instructor approved methods.

Impact

This project has the potential to enhance ELOT education to form the next group of holistic therapists, underscore how spirituality can be included in curriculum without explicit statement in current ACOTE standards, and as a threshold concept, change theoretical approach to evaluation and assessment.

Future Study Recommendations

Areas for further study include investigation of impact of later versus early introduction of spirituality in the curriculum impacts theoretical lens for future courses, inclusion of spirituality learning module in biomedical courses, and cultural impacts on therapist patient relationships for addressing spirituality. Future study should include the implementation of suggestions and repetition of the study to see if errors in grammar, unclear content, lack of evidential support, infeasibility of evaluation methods, and unclear activities could impact findings.

References

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process fourth edition. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(2). View

Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. (1997). Enabling occupation: An occupational therapy perspective. Ottawa, ON: CAOT Publications ACE. View

Piderman, K. M., Lapid, M. I., Stevens, S. R., Ryan, S. M., Somers, K. J., Kronberg, M. T., et al. (2011). Spiritual well being and spiritual practices in elderly depressed psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 65(1), 1-11. View

Hermann, C. (2006). Development and testing of the spiritual needs inventory for patients near the end of life. Oncology Nursing Forum, 33(4), 737-744. View

Egan, M. and Swedersky, J. (2003). Spirituality as Experienced by Occupational Therapists in Practice. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57(5), 525-533. View

Thompson, B. E., & MacNeil, C. (2006). A phenomenological study exploring the meaning of a seminar on spirituality for occupational therapy students. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 60(5), 531-539. View

MacGillivray, P. S., Sumsion, T., and Wicks-Nicholls, J. (2006). Critical elements of spirituality as identified by adolescent mental health clients. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(5). View

Morris, D., Stecher, J., Briggs-Peppler, K., Chittenden, C. M., Rubira, J. & Wismer, L. K. (2014). Spirituality in occupational therapy: Do we practice what we teach? Journal of Religion and Health, 53(1), 27-36. View

Mthembu, T. G, Ahmed, F., Nkuna, T. & Yaca, K. (2015). Occupational therapy students' perceptions of spirituality in training. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(6), 2178-2197. View

Mthembu, T. G., Roman, N. V., & Wegner, L. (2016). A cross- sectional descriptive study of occupational therapy students' perceptions and attitudes towards spirituality and spiritual care in occupational therapy education. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(5), 1529-1545. View

Hooper, B., Molineux, M., & Wood, W. (2020). The subject- centered integrative learning model: A new model for teaching occupational therapy’s distinct value. Journal of Occupational Therapy Education, 4(2). View

Brémault-Phillips, S. (2018). Spirituality and the metaphorical self-driving car. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 85(1), 4-6. View

Gijsberts, M. H. E., Echteld, M. A., van der Steen, Jenny T, Muller, M. T., Otten, R. H. J., Ribbe, M. W., et al. (2011). Spirituality at the end of life: Conceptualization of measurable aspects—a systematic review. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 14(7), 852-863. View

Griffith, J., Caron, C. D., Desrosiers, J., & Thibeault, R. (2007). Defining spirituality and giving meaning to occupation: The perspective of community-dwelling older adults with autonomy loss. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(2), 78-90. View

Le Roux, F. H. (2016). Integration of spirituality, music and emotions in health care. Music and Medicine (Online), 8(4), 162-169. View

Smith, S., & Suto, M. J. (2012). Religious and/or spiritual practices: Extending spiritual freedom to people with schizophrenia. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D'Ergotherapie, 79(2), 77-85. View

Monod, S., Brennan, M., Rochat, E., Martin, E., Rochat, S., & Büla, C. (2011). Instruments measuring spirituality in clinical research: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(11), 1345-1357. View

Burroughs, M. (2020). Moving Mountains: Facing Stokes with Faith and Hope. Xulon Press. View

Laures-Gorel, J., Lambert, P. L., Krugerl, A. C., Lovel, J., Davis, D. E. (2018) Spirituality and post-stroke aphasia recovery. Journal of Religion and Health, 57(1), 1876-1888. View

Meyerson, D. E., and Zuckerman, D. (2019). Identity Theft: Rediscovering Ourselves After Stroke. Andrews McMeel Publishing. View

Monod, S., Martin, E., Spencer, B., Rochat, E., & Büla, C. (2012). Validation of the spiritual distress assessment tool in older hospitalized patients. BMC Geriatrics, 12(1), 13. View

Monod, S. M., Rochat, E., Büla, C. J., Jobin, G., Martin, E., & Spencer, B. (2010). The spiritual distress assessment tool: An instrument to assess spiritual distress in hospitalised elderly persons. BMC Geriatrics, 10(1), 88. View

Mthembu, T. G., Ahmed, F., Nkuna, T., Yaca, K. (2015). Occupational Therapy Students’ Perceptions of Spirituality in Training. Journal of Religion and Health, 54 (6): 2178–2197. View

Ano, G., & Vasconcelles, E. (2005). Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(4). View

Mundle, R. G. (2012). Engaging religious experience in stroke rehabilitation. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(3), 986-998. View

Thompson, K., Cercle, W., Keele, L., Gaudet, S., Hanson, M., Sauer, W., & Gee, B. (2016). We’ve moved past sex: Can we now address religion? American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 70, 7011505114p1. View

Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (2018). 2018 Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (ACOTE®) Standards and Interpretive Guide. ACOTEonline.org View

Marchioni and Cunningham. (2020). Sense of connection: addressing spirituality in occupational therapy practice. OT Practice Magazine. View

Svinicki, M. D., & McKeachie, W. J. (2014). McKeachie’s teaching tips: Strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers (14th ed.). Cengage Learning. View

Zoom Video Communications, Inc. (2021). Zoom Security. Zoom.us. View

Cao, Y., Ajjan, H., & Hong, P. (2013). Using Social Media Applications for Educational Outcomes in College Teaching: A Structural Equation Analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(4):581–593. View

Ambrose, S., Bridges, M., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M., Norman, M. (2010). How does students’ prior knowledge affect their learning. How Learning Works 7 Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching (10-39). San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons Inc. View

Reimer-Kirkham, S., Sharma, S., Pesut, B., Sawatzky, R., Meyerhoff, H., Cochrane, M. (2011). Sacred spaces in public places: religious and spiritual plurality in health care. Nursing Inquiry, 19(3), 202-212. View