Journal of Rehabilitation Practices and Research Volume 7 (2026), Article ID: JRPR-195

https://doi.org/10.33790/jrpr1100195Research Article

Integrating Assignments into Occupational Therapy Education: Linking Experiential Learning and Technology Application

Naomie Corro, OTD, OTR/L, BCP

Assistant Professor, School of Health Care Professions, Missouri State University, Occupational Therapy Program, 901 S. National Ave. Springfield, MO 65897, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Naomie Corro, OTD, OTR/L, BCP, Assistant Professor, School of Health Care Professions, Missouri State University, Occupational Therapy Program, 901 S. National Ave. Springfield, MO 65897, United States.

Received date: 03rd December, 2025

Accepted date: 15th January, 2026

Published date: 19th January, 2026

Citation: Corro, N., (2026). Integrating Assignments into Occupational Therapy Education: Linking Experiential Learning and Technology Application. J Rehab Pract Res, 7(1):195.

Copyright: ©2026, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

This study examined the impact of integrating 3D printing assignments into an occupational therapy (OT) curriculum based on students’ experiential learning, knowledge, and perceptions of relevance to practice. With growing interest in maker technologies and assistive device design, 3D printing offers a meaningful avenue for hands-on, creative learning. An exploratory one-group, pretest posttest, repeated-measures design was conducted over six weeks with second-year entry-level OT students (N = 26) at a single academic institution. A survey questionnaire, developed by aligning Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle (ELC) with the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), measured changes in perceived relevance to OT practice, knowledge of 3D printing, and perceptions of curricular integration. Results from one-sample z tests showed statistically significant increases in perceived relevance (p = .03), knowledge (p < .001), and curricular integration (p = .016) following the assignment. These findings support the integration of 3D printing as an experiential learning strategy to strengthen OT students’ understanding of assistive technology and its application in practice. Implications for OT education highlight the value of curriculum design approaches that foster innovation, problem-solving, and client- centered thinking through the adoption of emerging technologies.

Keywords: Assistive Technology, OT Education, Experiential Learning, Curriculum Development, Instructional Strategies, 3D Printing

Introduction

In recent years, assistive technology has attracted more attention in the healthcare field. Designing and creating customized assistive device solutions without relying on costly commercialized tools in the market allows for an affordable intervention within the context of many environments [1]. 3D printing is one of several methods used to create personalized devices that support client engagement and participation in activities of daily living [2,3], and it may provide more affordable and longer-lasting options compared to other approaches [4]. These devices may include a range of tools designed to assist with task completion, such as grips for writing utensils and adaptive holder for feeding, key holders, can openers, as well as adapted video game controllers. The concept of 3D printing has been expanded to broader medical applications, including tissue and organ fabrication, implants and prosthetics, and pharmaceutics [5]. Within the field of OT, the integration of 3D printing is gaining practical application for client use such as the use of adaptive devices in community and school systems [6]. “Emerging research supports 3D printing can provide customizable, low-cost, and replicable items for application in occupational therapy, but more research is necessary to inform occupational therapists on why and how 3D printing would be applicable and feasible in practice” [7].

Review of Literature

Entry-level OT education emphasizes andragogical principles that actively engage students in applying knowledge to practice, with specific attention to preparing them to evaluate and implement technologies that enhance client engagement and quality of life [8,9]. Thus, OT Programs must provide hands-on and experiential learning opportunities that integrate technology and environmental adaptation (e.g. [ACOTE®] 2023 standards A.4.1, B.4.1, D.2.3). These standards highlight the need for students to demonstrate evidence-based reasoning in selecting and adapting assistive technologies, including the ability to justify how modifications enhance occupational performance, support meaningful participation, and improve well being. Contemporary learners (often described as “digital natives”) also expect interactive and technology-integrated instruction [10]. Studies confirm OT students’ preference for experiential and multimodal teaching approaches [11], and early investigations suggest that incorporating 3D printing into coursework enhances students’ acceptance of the technology [12].

Experiential learning is a key component in OT education, supporting the development of clinical reasoning by integrating theoretical knowledge with practical application through active participation and reflection [13,14]. According to Sewchuk [15], experiential learning provides a “theoretical framework for bridging the gap between theory and practice” (p. 1311), underscoring the importance of applying hands-on strategies in professional curricula. Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (1984) frames this process as a cycle of concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation [14]. A well designed 3D printing assignment provides a unique opportunity to engage OT students across this cycle: fabricating adaptive tools for ADLs and IADLs (concrete experience), reflecting on their usability (reflective observation), applying theoretical frameworks to design choices (abstract conceptualization), and refining tools through iterative testing (active experimentation). The integration of emerging technologies into OT education is further informed by the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which highlights the importance of perceived usefulness and ease of use in shaping adoption [16]. Engagement with 3D printing, therefore, depends not only on students’ learning experiences but also on their confidence and recognition of its potential to enhance client-centered care and innovation.

In response to recent calls in the literature to evaluate the integration of technology in OT curricula [7,13,17] faculty at Missouri State University implemented a survey to OT students to examine the impact of a 3D printing course assignment. The survey targeted three key variables: (1) the relevance of 3D printing to clinical fieldwork and professional practice, (2) students’ knowledge and confidence in using 3D printing technology, and (3) the perceived value of incorporating 3D printing into the OT curriculum. These variables were deliberately aligned with Kolb’s ELC and the TAM, creating a comprehensive framework for evaluating both learning outcomes and technology adoption. Guided by this framework, the study tested the overarching hypothesis that integrating a 3D printing assignment into OT education would significantly enhance students’ experiential learning and technology acceptance, as evidenced by increased perceptions of relevance, knowledge, and curricular value.

Methods

Research Design

The study comprised of repeated measures pre- and post- survey questionnaire on Qualtrics with anonymized data collection. The questionnaire was distributed online between September and December 2024.

Participants

Participants (n = 26) were OT students recruited from the Fall Semester 2024 Assistive Technology course in Missouri State University OT Program. This reflects the total number of OT students enrolled in one cohort of entry-level Master’s degree. Students were currently in their second year of the OT Program for the duration of the study.

Ethical Considerations

Approval was obtained from the ethical review committee of Missouri State University’s Office of Research Administration (IRB FY2025-65) prior to conducting the study. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant for their voluntary participation and that non-participation or withdrawing at any time would not result in academic or personal disadvantage. All data were anonymized and stored securely in compliance with institutional policies and ethical research standards.

Procedure

To eliminate potential bias, OT faculty announced the opportunity to participate in an online study two weeks prior to the scheduled lecture content on 3D printing. After signing an electronic informed consent, the students proceeded in completing the pre-test survey questionnaire before the day of the scheduled lecture content in class. The 3D printing lecture content created by OT faculty was 165 minutes in duration and was implemented in class after the student sample (N=26) completed the pretest. Within that lecture time duration, students were provided with introduction to 3D printing, and the value of 3D-printed adaptive devices and steps involved in creating them were explained. Students were also provided practical examples in designing and exploring potential clinical applications and troubleshooting devices as need arises. Students were then placed into smaller groups of four (except for 2 groups of five members) as they received guidance on how to operate the 3D printers. One 3D printer was available for use and was strategically placed in a separate research room to ensure safety with adequate ventilation as needed, away from student classrooms and faculty offices [18]. Following group work and device fabrication, students completed reflection papers and delivered peer presentations to share their projects and experiences. The posttest survey was administered after students had completed the 3D printing assignment.

Lesson Plan

The lecture and assignment were designed with the following learning objectives:

1. Apply 3D printing technology in OT by selecting, modifying, and printing an adaptive device for various areas of occupation based on the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework–4th edition [19].

2. Explain the kinesiology, biomechanics, and physics principles underlying the device’s design and function.

3. Justify the device’s use by explaining how it enhances quality of life, occupational performance, and overall participation.

Each student group selected a unique 3D project for printing, with faculty approval required to prevent duplication. Groups considered project complexity to ensure print time did not exceed five hours. Because only one printer was available, students collaborated across groups to coordinate scheduling and timely project completion. The 3D printing assignment was completed over six weeks during the Fall 2024 semester and involved the following steps:

1. Researching and Selecting a 3D Model:'

° Locate an appropriate adaptive tool addressing a specific client need in ADLs or IADLs (e.g., modified utensils, key turners, jar openers, pill containers) [19].

° Use open-source databases such as Thingiverse or GrabCAD to identify designs [20].

° Provide a rationale for the project and identify a target population (e.g., individuals with arthritis, stroke survivors) [21].

2. 3D Model Preparation:

° Download the model file (preferably in. STL format) [22].

° Prepare the model in slicer software, adjust as needed for therapeutic usability, and save in G-code format [23].

° Document the preparation process, such as capturing evidence (e.g., a screenshot of the model ready for printing) [24].

3. 3D Printing Process:

° Schedule a printing session and print the adaptive tool.

° Document the process with photos or videos, noting challenges and solutions.

° Maintain a log of total print time and encountered difficulties.

4. Reflection and Application:

° Write a 300–400 word reflection discussing the experience of using 3D printing in OT.

° Address potential clinical applications, benefits, and challenges of integrating 3D printing into practice.

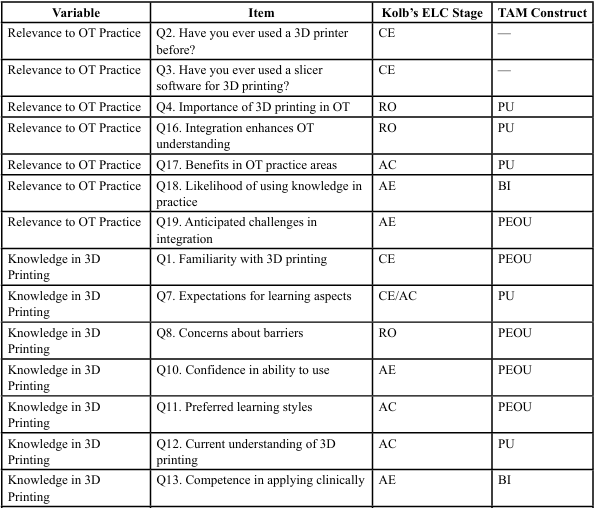

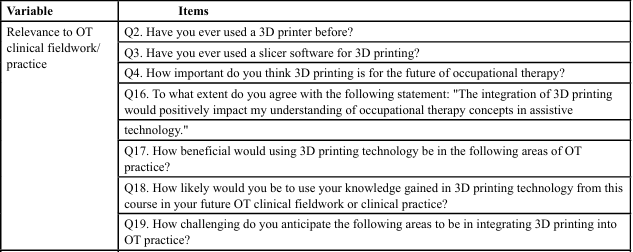

Materials and Measurements

To evaluate the effectiveness of the lesson plan for 3D printing lecture and course assignment, we developed a 19-item questionnaire aligned based on Kolb’s ELC and TAM framework. Items emphasized perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU)- core constructs of the TAM- in order to reflect their influence on user acceptance and behavioral intention [16,25]. To strengthen applicability to OT education, items were also conceptually aligned with Kolb’s ELC, which frames learning as a cycle of concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation [14]. This dual alignment allowed the instrument to capture both students’ learning processes and their acceptance of emerging technology. Kolb’s theory captures the learning process by describing how students’ progress through stages of exposure, reflection, conceptualization, and application. In contrast, the TAM model explains the process of technology adoption by emphasizing perceptions of usefulness, ease of use, and the intention to apply technology in practice. Together, these frameworks provide complementary perspectives: Kolb’s ELC highlights how students acquire and apply knowledge, while TAM addresses the factors that influence whether students will embrace and integrate new technologies, such as 3D printing, into OT practice. Each item created on the questionnaire domains were mapped into both constructs as detailed in Table 1. The questionnaire was administered in pre- and post- intervention via Qualtrics, with all responses anonymized. The questionnaire was organized into three variables:

1. Relevance of 3D Printing to OT Practice – Items from this variable reflect perceptions of professional significance and applicability to clinical fieldwork and future practice, aligning with Kolb’s reflective observation and active experimentation, and TAM’s PU and behavioral intention.

2. Knowledge in 3D Printing – Items from this variable reflect familiarity, confidence, and competence in using 3D printing technology, corresponding to Kolb’s concrete experience and abstract conceptualization, and TAM’s PEOU.

3. Integration of 3D Printing into the OT Curriculum – Items from this variable reflect perceptions of the educational value of embedding 3D printing in coursework, reflecting all four Kolb stages as well as TAM’s PU, PEOU, and behavioral intention.

The survey questionnaire instrument was reviewed by an OT faculty member with expertise in assistive technology and a staff from Research, Statistical Training, and Technical Support Institute (RSTATs) of Missouri State University to ensure clarity, relevance, and appropriateness for the student population. Reliability analysis yielded acceptable internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values of .82 (knowledge), .85 (relevance), and .88 (integration), indicating strong reliability across domains. A detailed outline of the pre- and post-survey questions is provided in Table 2.

Results

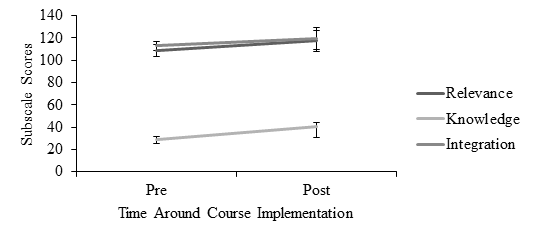

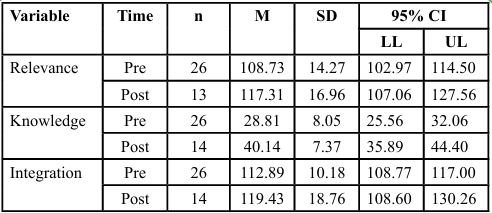

OT students (n = 26) were surveyed prior to and after the implementation of a 3D printing course assignment as to its relevance, knowledge, and integration. Before implementation, only three of the students indicated that they had used a 3D printer (11.54%). Further, only one indicated that they used slicer software for 3D printing (3.85%). All subscale items were rated on a scale from 1 to 10, with the ranges of possible summary scores as follows: relevance (16 160), knowledge (6-60), and integration (18-180). See Figure 1 for a visual depiction of the results.

Prior to running the analyses, the data was screened for accuracy, missing values, outliers, and the assumption of normality. Of the 26 students that responded to the pre survey, 15 were retained on the post survey. On the post survey, two participants were missing > 5% of their data and were excluded pairwise from the analyses. No significant outliers were found, as indicated by z scores < |+ 3|. The assumption of normality was met, as indicated by Shapiro-Wilk test ps > .001 [26].

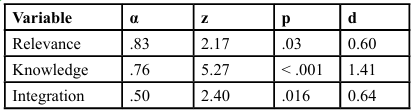

Reliability and Item Analyses

Three reliability and item analyses were performed on pretest data to assess the psychometric properties of the instrument for the three variable subscales, namely perception of 3D printing in OT relevance, knowledge, and integration subscales, with IBM SPSS Statistics software (Version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The Cronbach’s alpha was used to calculate the 3 variables: for the relevance subscale was α = 0.83 with good internal consistency; knowledge subscale was α = 0.76 with acceptable internal consistency and individual subscale item yielded positive correlation coefficients of above 0.30; integration subscale was α = 0.50 with acceptable internal consistency. One sample z tests were performed to determine whether the post-test data for perceptions of 3D printing in OT relevance, knowledge, and integration significantly differed from pre-test implementation perceptions – these were treated as the population parameters [27]. This analysis was performed in lieu of the paired samples t test, as identifiers were not collected. There was a statistically significant difference in perceived relevance, z = 2.17, p = .03, d = 0.60. Particularly, there was a moderate increase in perceived relevance from pre- (M = 108.73, SD = 14.27) to post- implementation (M = 117.31, SD = 16.96). There was a statistically significant difference in perceived knowledge, z = 5.27, p < .001, d = 1.41. There was a substantial increase in perceived knowledge from pre- (M = 28.81, SD = 8.05) to post-implementation (M = 40.14, SD = 7.37). Further, there was a statistically significant difference in perceptions of integration, z = 2.40, p = .016, d = 0.64. Particularly, there was a moderate increase in perceptions from pre- (M = 112.89, SD = 10.18) to post-implementation (M = 119.43, SD = 18.76). This suggests that the OT students’ perceptions in terms of relevance, knowledge, and curriculum integration improved after the implementation of the 3D printing course lecture and assignment. See Tables 3 and 4 for the statistical output and descriptive statistics.

Discussion

This study introduced 3D printing of self-help devices to OT students and assessed its impact to experiential learning through pre- and post-test questionnaires developed and aligned based on Kolb’s ELC and TAM model. The primary findings revealed that students increased their perceived relevance, knowledge, and integration of 3D printing concepts through combined didactic and practical hands-on components of a course assignment. The students understanding 3D printing and its relevance towards its use on OT significantly improved from pre to post-test measure with the largest effect size (d = 1.41). The large effect size confirms that the entire process of the educational assignment, from 165-minute lecture on 3D printing to actual fabrication of 3D devices based on clinical cases, was successful in meeting the primary learning objectives of improving student experiential learning. The students not only received an introduction to 3D printing concepts but also learned troubleshooting strategies as they navigate the actual hands-on process of 3D device fabrication. The course assignment gave students the chance to explore various existing 3D printed assistive tools and helped improve their confidence in 3D printing. These outcomes align with Kolb’s ELC, which frames learning as a progression through concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation [14]. In this study, students engaged in concrete experience by fabricating adaptive devices, reflective observation by assessing usability and discussing challenges, abstract conceptualization by integrating OT frameworks and theoretical principles into their designs, and active experimentation by refining devices and applying learned strategies in peer projects. The large effect size suggests that moving through all stages of Kolb’s cycle enhanced students’ understanding and confidence in using 3D printing technology.

There was a statistically significant difference in student perceptions of both relevance of 3D printing to OT curriculum (d = 0.60) and perceptions of integration of 3D concepts (d = 0.64). Specifically, Q16-Q19 in Table 2 demonstrates reflective observation and abstract conceptualization, as students deepened their understanding of 3D printing’s clinical utility while recognizing potential barriers. Responses to these questions on the posttest questionnaire revealed that students greatly enhanced their conceptual understanding of 3D printing and its clinical application to OT and considered as useful tool in their education and future clinical roles. Additionally, Q6, Q9, Q14-Q15 in Table 2 provided a multifaceted look at students' abstract conceptualization and active experimentation, capturing how students viewed 3D printing as a tool for creativity, problem- solving, and experiential learning within the curriculum. Responses to these questions on the posttest questionnaire revealed that students favorably rated assignment content (clinical areas), met learning outcomes (skills like problem-solving and creativity), and enhanced motivation and confidence. The results also align with TAM, as student responses demonstrated growth in both perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU), which in turn supported behavioral intention (BI) to adopt 3D printing in future practice. As highlighted in prior research, technology adoption requires both confidence in usability and recognition of value [12,17]. This study’s design addressed both by combining theoretical instruction with experiential activities, reflection, and peer presentations, thereby reinforcing both Kolb’s cycle of learning and TAM’s constructs of technology acceptance.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that integrating 3D printing into OT education not only advances experiential learning but also promotes readiness to adopt emerging technologies. By engaging students across Kolb’s four stages of learning while addressing TAM’s determinants of adoption, the 3D course assignment provided a comprehensive educational experience that fostered innovation, problem-solving, and clinical applicability. Our findings align with Sewchuk’s [15] assertion that experiential learning helps bridge the gap between what students learn conceptually and how they apply it in practice.

Implications for Occupational Therapy Education

Creating meaningful content for OT students presents distinct challenges, particularly in balancing OT foundational knowledge with clinical relevance. The course assignment was intentionally streamlined to focus on the core information OT students need to start applying 3D printing in clinical settings. In this study, the basic structure of the 6-week completion of 3D printing course assignment may be useful to develop an OT experiential learning assignment and may enhance students' perceived relevance and knowledge of 3D printing technology in entry-level OT programs.

Findings in this study indicated that in OT education it may be important to prioritize learning approaches that are highly experiential and interactive. This study may provide insight in determining where and how to embed 3D printing meaningfully within didactic and laboratory experiences, ensuring it adds value to student learning. The student responses suggested that 3D printing course assignments aligned with active learning strategies and deepened student engagement, reflection, and clinical reasoning within OT coursework. Students believed that 3D printing supports key aspects of OT training critical thinking, innovation, and client- centered application which are central to OT curriculum goals.

Importantly, OT faculty do not need to be experts in 3D printing technology to implement such assignments. Instead, they should be proficient in operating a 3D printer and knowledgeable about its application in OT practice, including benefits, limitations, and practical relevance. With this foundation, faculty can guide students in using 3D printing as a tool to support occupational performance, enhance participation, and improve quality of life for clients.

Limitations

This study has several limitations.

First, the study employed a one-group, pretest–posttest design without a control group, which limits the ability to attribute changes solely to the intervention. Future studies should consider incorporating comparison groups or randomized controlled designs to strengthen causal inference. Second, the sample size (N = 26) was drawn from a single academic institution, which may limit the generalizability of findings to other OT programs and student populations. Third, although the questionnaire was carefully designed and aligned with Kolb’s ELC and the TAM model, OT students’ self-report data may be subject to response bias.

In addition, despite the instructor’s effort to make the pretest questionnaire available two weeks prior to the scheduled lecture, some students may have conducted preliminary readings on 3D printing that influenced their baseline responses. Difficulties with 3D printer operation also occurred, particularly nozzle clogging, which interrupted fabrication time and may have shaped student perceptions of 3D printing as overly complex. Time constraints were further compounded by limited access, as only one printer was available, highlighting cost as a potential barrier to broader adoption in OT education and clinical settings.

Finally, although this study applied rigorous quantitative analysis, it did not include qualitative methods to capture the depth of student experiences. Future studies should incorporate qualitative reflections to better understand how students perceive the impact of experiential learning with 3D printing and further examine how such learning translates into clinical practice. Additionally, exploring long-term outcomes, cost-effectiveness, scalability, and integration with interprofessional education could provide valuable insights into sustainable curricular design.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that integrating 3D printing lectures and assignments into an OT curriculum significantly enhanced students’ perceptions of relevance, knowledge, and curricular value of 3D printing. By aligning Kolb’s ELC with the TAM model, the study effectively captured both learning processes and technology acceptance, showing that experiential learning strategies embedded in 3D lesson plan and OT curriculum can strengthen students’ confidence and readiness to apply emerging technologies in practice. The findings suggest that embedding 3D printing into OT education provides meaningful opportunities for students to develop problem solving, innovation, and client-centered thinking skills that are essential for future clinical practice. For future research, extending this approach to include student-designed assistive devices tested in diverse clinical contexts may further prepare graduates to apply innovative, client-centered solutions and expand the role of 3D printing in OT practice.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the Office of Research, Statistical Training, and Technical Support Institute for their support with the statistical analysis of the data; my colleague Dr. Jennifer Yates, OTD, OTR/L for her support of my research on integrating 3D printing into the Assistive Technology course curriculum; and the Faculty Center for Teaching and Learning (FCTL) for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) grant award, which supported the purchase of the 3D printer.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Slegers, K., Krieg, A. M., & Lexis, M. A. S. (2022). Acceptance of 3D Printing by Occupational Therapists: An Exploratory Survey Study. Occupational Therapy International, 2022, Article 1–9. View

Morgan, M., & Schank, J. (2018). Making it work: Examples of OT within the maker movement. OT Practice, 23(14), 19–22. View

Schwartz, J. (2018). A 3D-printed assistive technology intervention: A phase I trial. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(4_Supplement_1), 7211515279. View

Ganesan, B., Al-Jumaily, A., & Luximon, A. (2016). 3D printing technology applications in occupational therapy. Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation International, 3(3), 1085. View

Ventola C. L. (2014). Medical Applications for 3D Printing: Current and Projected Uses. P & T : a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management, 39(10), 704–711. View

Buehler, E., Kane, S. K., & Hurst, A. (2014). ABC and 3D: Opportunities and obstacles to 3D printing in special education environments. Proceedings of the 16th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS ’14), 107–114. View

Hunzeker, M., & Ozelie, R. (2021). A cost-effective analysis of 3D printing applications in occupational therapy practice. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 9(1), 1–12. View

Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (2018). 2018 Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (ACOTE®) standards and interpretive guide. ACOTE. View

Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (2023). 2023 Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (ACOTE®) standards and interpretive guide. ACOTE. View

Phillips, R., & Trainor, S. (2014). Exploring digital natives’ perceptions of learning: An experiential approach. International Journal of Educational Technology, 1(2), 45-56.

Brown, T., Wickes, S., & Davison, M. (2008). Australian occupational therapy students’ learning preferences and attitudes towards technology. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 55(3), 180–187.

Benham, S., & San, S. (2020). Student technology acceptance of 3D printing in occupational therapy education. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(3), 7403205060. View

Henderson, W., & Coppard, B. (2018). Identifying instructional methods for development of clinical reasoning in entry- level occupational therapy education. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(4), 1-20. View

Kolb, D. A. (2015). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (2nd ed.). Pearson Education. View

Sewchuk, D. (2005). Experiential learning A theoretical framework. AORN Journal, 81(6), 1311–1318. View

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. View

Harada, Y., Sawada, Y., Suzurikawa, J., Takeshima, R., & Kondo, T. (2022). Short-term program on three-dimensional printed self-help devices for occupational therapy students: A pre-post intervention study. Journal of Occupational Therapy Education, 6(3), 1–20. View

Yi, L. Y., Li, J., Chen, X., & Wong, C. (2016). Controlling emissions from 3D printing via an integrated ventilation system. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 13(7), 547–555.

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl. 2), 7412410010p1–7412410010p87. View

Nilsiam, Y., & Pearce, J. M. (2017). Free and open source 3-D model customizer for websites to democratize design with Open CAD. Designs, 1(1), 1–15. View

Cabrera, M. E., & Hill, B. (2021). Using 3D printing to support occupation-based interventions in occupational therapy education. Journal of Occupational Therapy Education, 5(3), Article 7.

National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). NIH 3D Print Exchange. View

All3DP. (2023). G-Code: The beginner’s guide. View

Blikstein, P. (2013). Digital fabrication and ‘making’ in education: The democratization of invention. In J. Walter Herrmann & C. Büching (Eds.), FabLabs: Of machines, makers and inventors (pp. 203–222). Transcript Verlag. View

Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, 46(2), 186–204. View

Shapiro, S. S., & Wilk, M. B. (1965). An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika, 52(3–4), 591–611. View

JASP Team. (2025). JASP (Version 0.19.3) [Computer software]. JASP. View