Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 2 (2024), Article ID: JSWWP-128

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100128Research Article

Evolution of Public–Private Partnership In the Construction of Long-Term Care Service Network in Taiwan: The Yun-Chia Region as an Example

Ming-Ju Wu1*, Hui-Ching Cheng2, Hong-Yu Liu3, and Yuxiang Zhou4,

1 Professor, Department and Institute of Social Welfare, National Chung Cheng University, No. 168, Sec. 1, University Rd., Minhsiung, Chiayi 621301, Taiwan.

2 PhD Candidate, Department and Institute of Social Welfare, National Chung Cheng University, No. 168, Sec. 1, University Rd., Minhsiung, Chiayi 621301, Taiwan.

3 Adjunct Assistant Research Fellow, Center for Innovative Research in Aging Society, National Chung Cheng University, 168, Sec. 1, University Rd., Minhsiung, Chiayi 621301, Taiwan.

4 Assistant professor, Department of Social Welfare, Chinese Culture University, 55, Hwa-Kand Rd., Yang-Ming-Shan, Taipei, Taiwan.

Corresponding Author Details: Ming-Ju Wu, Professor, Department and Institute of Social Welfare, National Chung Cheng University, No. 168, Sec. 1, University Rd., Minhsiung, Chiayi 621301, Taiwan.

Received date: 20th August, 2024

Accepted date: 18th November, 2024

Published date: 20th November, 2024

Citation: Wu, M. J., Cheng, H. C., Liu, H. Y., & Zhou, Y., (2024). Evolution of Public–Private Partnership In the Construction of Long-Term Care Service Network in Taiwan: The Yun-Chia Region as an Example. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 2(2): 128.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Scholar Esping-Andersen proposed the following five intellectual innovations for the new welfare state: the emergence of new social risks, insufficient carrying capacity of the welfare state, importance of vulnerable phases in the dynamic life course, need for a new gender contract to elevate women’s roles, and empowerment-based social justice. Consequently, the new risks of an aging society and the fiscal sustainability pressures on governments have triggered the concepts of “public–private partnerships” and “network governance,” which gained widespread attention following the challenges of new public governance and managerialism. In Taiwan, the development of long-term care policies and services has evolved from the pluralistic welfare and community care trends implied in Long-term Care 1.0 and continuing in Long-term Care 2.0. The latter policy aims to foster concepts such as symbiotic communities and co-production. Initiatives regarding social investment orientation, such as social prescriptions and time banks, have also attracted attention. The community and nonprofit organizations has once again become a focal point, envisioned as a platform for public–private partnerships and resource integration by the government. This trend has led to a greater number of connections and discussions between social policy and social innovation practices.

This study uses secondary data analysis methods, using policy retrospective, induction and network analysis methods to explore the community's long-term care 2.0 system in Taiwan and its promotion and deployment in the Yunlin and Chiayi region where long-term care resources are relatively scarce. The study found that the private sector (community) usually requires the intervention of the public sector (government) in the early stages of development, but long-term intervention can easily affect the self- governance development of the community. The implementation of public-private collaboration affects the establishment of an integrated community care system to a great extent, and the more nearby Rural areas in cities are more likely to be ignored by the formal service delivery system. Especially if there is a lack of a linking mechanism between the public and private sectors, the effectiveness and efficiency of service delivery may be compromised, causing service users to choose to use other channels. To meet the needs, the informal care resources hidden in the community are an aspect that government departments cannot ignore.

Keywords: Public–Private Partnerships, Network Governance, Community, Long-Term Care

Development and Challenges of Taiwan’s Long-term Care 2.0 System

Taiwan’s Rapid Population Aging

According to the National Development Council, in 2020, over 10% of the Taiwanese population was older than 85 years. Taiwan became an aged society in 1993 and is expected to transition into a super-aged society by 2025 [1]. In response, the Ministry of Health and Welfare launched the Long-term Care 2.0 policy (2017–2026) to improve and expand the Long-term Care 1.0 services initiated in 2007. In addition to increasing the volume of services, Long-term Care 2.0 focuses on the hierarchical and integrated service capacities of service units, establishing different service models based on the needs of care recipients and linking local service units through the Long-term Care ABC mechanism. Since the implementation of the service unit hierarchy, resources at local A, B, and C points have been integrated. Most long-term care service units are non-profit foundations or associations, with C-level neighborhood care stations incorporating local medical units. Although in 2013, the government pledged to construct a long-term care service network, and despite the subsequent organizational reforms in the executive Yuan, long-term care responsibilities have remained divided between the Department of Nursing and Health Care, the Social and Family Affairs Administration, and the Long-term Care Administration established in 2019. Furthermore, although a long-term care evaluation system has been introduced, service quality and quantity disparities persist between urban and rural areas, with inadequate caregiving personnel often considered the most severe problem in the implementation of Long-term Care 2.0 [2-4].

The A-level units, known as “flagship stores” of long-term care, are responsible for integrating and connecting resources at B and C points, which makes the case managers’ (referred to as A-case managers) workload critical to the quality of care. According to the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the A-case managers’ duties include discussing and adjusting care plans, linking long-term care services, monitoring service quality, and serving as complaint channels, essentially coordinating between cases and external resources. However, due to their role in coordinating external resources, care recipients’ expectations regarding A-case managers may exceed the scope of long-term care, leading to requests for non-essential services beyond long-term care benefits. Furthermore, the qualifications of A-case managers often do not meet the required standards, which limits their effectiveness [5] and makes it difficult to achieve the government’s goals of attaining small institutions with multiple functions and developing multi-skilled professionals.

A-Level Units as Key Hubs in Public–Private Partnerships (Axis)

From this perspective, the role of A-case managers in coordinating external resources seems limited, and this limitation is understandable. Some studies have pointed out that A-case managers are in a triangular ambiguity between the long-term care management center, B-level units, and professionals; their workload, currently managing a caseload rating 1:150, often prevents them from listening attentively and comprehensively assessing the overall needs of older adults and their families, often focusing solely on "long-term care service" needs, neglecting the importance of life goals in enhancing the quality of life for older adults [6].

Furthermore, addressing the diverse and complex long-term care needs of older adults and the service systems of different professions, integrated care has become a major direction in long-term care policy development worldwide. Thus, the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) and Community-Based Supports and Services (CBSS) in the United States aim to integrate cross-professional teams to assist older adult home care and avoid nursing home admissions. PACE provides integrated community-based service teams, including physicians, nurses, social workers, therapists, caregivers, and drivers, without increasing costs. The CBSS emphasizes community strength and enhances the older adult’s life focus, primarily supported by volunteers [7]. The World Health Organization also proposed five long-term care integration mechanisms [8,9], while Evashwick [10] identified the following four main integration aspects as crucial for implementation:

1. Organizational Management: Coordination and cooperation between organizations are prerequisites for long-term care integration mechanisms.

2. Case Management: Assisting cases in connecting with different organizations and integrating their resources.

3. Information Integration Sharing case information among different service organizations to reduce the costs of repetitive information verification.

4. Financial Integration: Providing the most needed services to cases based on capitation under fixed funding, believed to reduce financial costs.

Despite the push for a community-based integrated care model (Long-term Care ABC) in Long-term Care 2.0, aiming to create a highly integrated service system through A-case managers’ planning and resource linkage, B-level units’ professional service delivery, and C-level neighborhood care stations’ convenient services, many practical challenges remain, including the following:

1. Professional Integration: As found by Chen et al. [11], different professionals possess different degrees of sensitivity to care, which results in opposite service linkage priorities; for example, social welfare personnel prioritize home services, while medical personnel focus on home medical or health care.

2. Case Management System Integration: Integrated care relies on case managers’ cross-department or service system coordination; however, many studies indicate that divided responsibilities between long-term care management center’s care coordinators and A-case managers often lead to unclear responsibilities and inconsistent contact points [6,12].

3. Case Information and Message Integration: Currently, the Ministry of Health and Welfare’s care service management information platform cannot facilitate discussion or viewing of other professionals’ service situations, directly impacting the implementation of cross-professional integration [12].

Cross-Department Collaboration Mechanisms Under Welfare Pluralism

Considering suppliers in the long-term care field, the early social welfare system was state-controlled. Later, some scholars argued that the operation of state systems was too rigid, forcing care recipients to follow established modes of support from national social welfare departments, with excessive bureaucracy hindering responsiveness to recipients’ needs [13,14]. Furthermore, the state’s full control of the social welfare system might undermine existing spontaneous social support systems, leading to the idea of transferring some welfare capacities to market and voluntary sectors, known as welfare pluralism. In the development of welfare pluralism, the division of welfare provision has evolved, with the most common classification including "state," "market," "voluntary sector," and the original source of care, "family," forming the "welfare diamond" [15]. The welfare diamond does not merely identify the roles of caregivers but describes how these four components integrate to support care recipients. Under the welfare diamond system, each pillar has its limitations. For instance, studies on European social welfare systems found that market semi-professionalization eroded family care and caused discrimination against care recipients [16], while state systems’ resource allocation involves welfare qualification recognition and service division for care recipients [17], non-profit organizations and community development associations are crucial resources in constructing long-term care safety nets. Thus, strengthening cross-department collaboration and partnerships becomes key to a robust long-term care service system.

Research Methodology

This study aims to explore three issues:

1. The evolution of welfare ideologies in Western welfare states, examining the context from the New Public Management to New Public Governance perspectives to understand the significance of Taiwan's long-term care system formation process.

2. Under the current Long-term Care 2.0 framework, investigating the current division of responsibilities between public and private sectors in promoting long-term care in various regions and identifying any issues pertaining to coordination and integration mechanisms.

3. Establishing cross-departmental collaboration, partnership, and integration mechanisms for long-term care services.

We employed a multimethod research approach that included secondary database analysis and a literature review. The secondary database analysis involves analyzing data from sources such as household income and expenditure surveys, statistics on long-term care service utilization, and middle-aged and older adult survey files to understand the economic capabilities and long-term care service use and expenditures across different family types, urban and rural areas, and income levels. Secondary data was obtained in part from a research project at the National Health Research Institutes directed by the author. The literature review method helps clarify the division of labor and responsibility boundaries between the public and private sectors in long-term care service systems across various countries (or welfare systems).

Due to the limitations in research resources and manpower, this study focused on the Yunlin and Chiayi regions, specifically selecting the townships of Dapi in Yunlin County and Xingang in Chiayi County. Both townships are characterized by a scarcity of long-term care resources. By observing changes in these townships after the implementation of Long-term Care 2.0, the study aimed to better understand the policy’s impact on local informal sectors and care recipients. However, the inferential limitations present one of the study’s constraints.

Western Welfare Policy Ideologies and Context

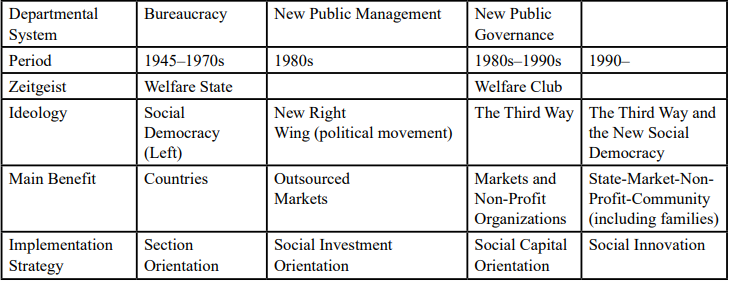

In the 1980s, amid economic turbulence, the golden age of the post-war welfare state ended, giving rise to neoliberalism, which emphasizes the market–consumer principle of efficiency and choice, replacing the traditional government–welfare beneficiary principle of the welfare state. Welfare policies shifted toward new managerialism or new public management as forward strategies. However, the excessive adoption of managerial welfare policies, particularly the strategy of outsourcing contracts, resulted in the cream skimming effect, where those truly in need were diluted by cost and performance principles1. After 2000, the emergence of the "third way" prompted the government to rethink focusing on client-centered welfare providers, which led to a new trend of partnerships between the government and the third sector. The new public service emphasizes community empowerment and the introduction of client empowerment concepts. Past welfare pluralism emphasized the separation of service and supply, but after 2000, the focus shifted to establishing collaborative relationships between the government and network units. The government no longer acted as the sole definer and resource guide for clients, leading to the formation of the new public governance ideology (Table3-1).

With the trend of new public governance, the role of non-profit organizations has become increasingly important. Governance logic aims to increase social significance in organizational operations through market mechanisms, promoting the spirit of social enterprises and social innovation, thereby changing the traditional public–private partnership model based on contract outsourcing. In addition, this trend shifts the welfare service relationship from a consumer to a producer model, achieving welfare effects through social network connections, changing the traditional production– consumption model to a co-production model.

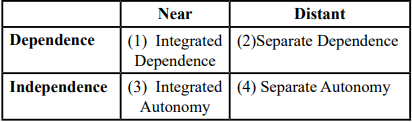

As shown in Table 3-2, Kuhnle and Selle [20] categorized the relationship between voluntary organizations and government departments based on dependency (financial and control) and closeness (communication and contact) into four types2:

1. Integrated Dependence: This model primarily involves labor market organizations, where voluntary organizations strengthen the labor market, which is a key concern for government departments.

2. Separate Dependence: In this model, the government's dominance and the influence of voluntary organizations are both low, but the freedom of action for voluntary organizations is strictly limited.

3. Integrated Autonomy: Based on pluralism, voluntary organizations can freely organize and influence public policy, but these actions cannot be integrated into decision-making or execution processes.

4. Separate Autonomy: The relationship between the public and voluntary sectors follows the principle of minimum state intervention.

Kuhnle and Selle [20] described the evolution of the relationship between voluntary organizations and public departments as transitioning from separate autonomy to integrated dependence. For example, in post-WWII Norway, the public sector gradually increased financial and welfare service provision, incorporating the voluntary sector into a unified welfare package and exemplifying the transition from separate autonomy to integrated dependence. In Taiwan's long-term care system, the use of public–private cooperation and partnerships is similar to the concept of transitioning from separate autonomy to integrated dependence, but the government is not focused on the labor market. Instead, it aims to integrate non-profit organizations into the government's long-term care service provision network through evaluation and performance management to achieve policy objectives.

Analysis of Public–Private Partnerships in Taiwan's Long-term Care

Cross-Departmental Division of Labor in Taiwan's Long-term Care

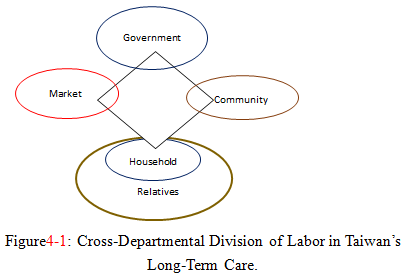

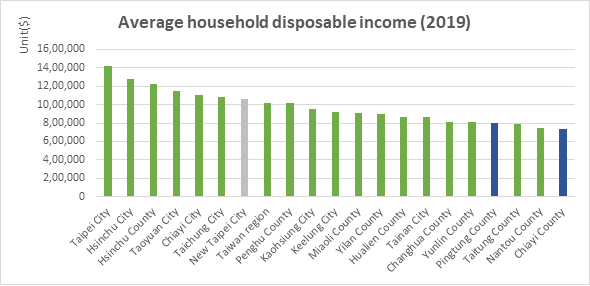

Welfare pluralism posits that welfare services are provided not only by the state but also by a range of providers, including the market. What constitutes a pluralistic system? Different scholars have different perspectives. Esping-Andersen [22] focuses on the state, market, and family, which form the welfare triangle. Recent studies have included a fourth sector (voluntary or community organizations), forming the welfare diamond or care diamond. Using this care diamond framework, this section explores the division of responsibilities among family, market, public sector, and non-profit sector in providing long-term care services. First, Ochiai [23] used the care diamond framework to examine the cross-departmental integration and division of responsibilities for childcare and older adult care in South Korea, China, Taiwan, Thailand, Singapore, and Japan. She argued that in these countries, most care responsibilities fall on families and the market as the primary providers. In other words, these countries exhibit a familistic welfare regime combined with liberalism. In Taiwan, although the state, market, and non-profit organizations have gradually taken on some older adult care responsibilities, the family remains the dominant provider. That is, family members, including relatives, are still the main caregivers, with the market playing a supportive role and the state and community providing limited support (see Figure 4-1).

Chan et al. [24] used the care diamond concept to explore the distribution of responsibilities for service provision and financing between government, market, family, and community in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China. The study found that in terms of service provision, the family plays the most crucial role, followed by the market, with government or community involvement being less significant. In terms of financial responsibility, the family again bears the heaviest burden, followed by the government, while the market and community’s involvement is minimal. In Taiwan, the family undoubtedly remains the primary service provider (Table4-1).

Table 4-1: Degree of Involvement in Long-Term Care Service Provision and Financial Responsibility in East Asian Countries

Zhou [25] used the concept of welfare mix to analyze the shifting boundaries of service provision and financing between the state, market, and family in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. The study found that in these four countries, the family initially played the main role in service provision. However, with rapid population aging and the gradual weakening of family functions, the state began to expand formal service systems. Unlike the Nordic model, where the state employs labor to provide services, these countries emphasize care services provided by non-profit organizations and professional groups. Thus, the boundaries of long-term care services among the state, market, and family are gradually moving toward non-profit organizations. However, Zhou [25] also noted that Taiwan’s heavy reliance on foreign caregivers suggests a market orientation stronger than that for non-profit organizations.

The above discussion reveals that in Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea, the family is frequently discussed as the primary caregiver, bearing the most responsibility. This aligns with the familistic welfare regime or Confucian welfare state in East Asian countries. However, with increasing attention to population aging in East Asia, the state’s role in long-term care governance is becoming increasingly significant, as seen in Japan’s implementation of long-term care insurance. Unlike the Nordic countries, where the government provides services directly, East Asian governments prefer to assume responsibility through subsidies and funding. In Taiwan, the increasing number of foreign caregivers each year highlights a significant market governance mechanism. Non-profit organizations, especially communities, are less discussed in the provision of long-term care services. Hence, in the care diamond model of government, market, community, and family, the market or family is the main driver of Taiwan’s long-term care model development. Although the government’s role is gradually increasing, it remains limited compared to other welfare states (e.g., the Nordic social democratic model), primarily focusing on funding rather than direct service provision.

Rise of Market Forces: The Foreign Caregiver Model

Taiwan opened up to foreign caregivers in 1992 as a strategy to address an aging society. In addition to the family, foreign caregivers, who are part of the market sector, have become one of Taiwan’s main service providers. Although the government initially positioned foreign caregivers as temporary and supplementary labor, their numbers have steadily increased. In 1992, there were a total of 306 foreign caregivers; by 2002, this number had risen to 113,755, reaching 200,530 in 2012, and by the end of 2020, Taiwan relied on 250,188 foreign caregivers for care services (Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, 2020). Despite the government's emphasis on the temporary and supplementary nature of foreign caregivers, statistics show that they have become a primary force in Taiwan's long-term care services, indicating a shift of care responsibilities from families to the market.

Liang and Su [26] pointed out that Taiwan has continuously relaxed the hiring standards for foreign caregivers. Initially, care recipients needed a Barthel Index score below 20, but due to pressure from social welfare groups and the public, it was relaxed to 35 and below. For individuals older than 80, the threshold was relaxed to 60 points, and in 2015, for those aged ≥85, even a single item disability qualified for hiring a caregiver. Consequently, with the government's relaxation of hiring standards, the number of foreign caregivers in Taiwan has steadily increased, becoming the main force in long-term care services.

Generally, the employment of foreign caregivers can be divided into two models: formal institutional and family care. The former involves foreign caregivers providing services in care institutions, while the latter involves foreign caregivers working in the homes of older adults. Liang and Su [26] and Chen [27] argued that although the family care model of foreign caregivers raises labor rights issues, it also preserves the traditional family culture of filial piety in East Asian countries, preventing its collapse. In other words, this is an employment model that maintains the cultural value of filial piety. The Confucian welfare state emphasizes care services provided by family members or relatives through blood or marriage. Although families hiring foreign caregivers are not providing care directly, they fully bear the financial responsibility because the government does not subsidize the hiring of foreign caregivers. Therefore, while families are relieved of most care responsibilities owing to foreign caregivers, they also fully shoulder the financial burden due to the government's retreat. In the context of changing family structures (e.g., increasing number of dual-income families), older people’s children outsourcing care responsibilities to foreign caregivers while bearing the financial burden helps avoid the stigma of placing parents in institutions and allows older adults to continue living at home. This care service model, which maintains home life for older adults through foreign caregivers while families bear the primary financial responsibility, aligns with the Confucian cultural emphasis on family responsibility. However, the responsibility has shifted from caregiving to financial, with the government playing a limited, supplementary role and the family remaining the main responsibility bearers.

At this stage, Taiwan's foreign caregiver model is characterized by the "migrant-in-the-family model," operating primarily through family and market logic, with the government playing a minimal role. As Ogawa [28] noted, Taiwan places the main care responsibility on families, with the government playing a limited role. Therefore, employment, mediation, and training and management of foreign caregivers are handled by the market or families. Families hiring foreign caregivers are excluded from the formal long-term care service system and must pay employment stability funds to the government. Taiwan's foreign caregiver policy reflects traditional East Asian characteristics: the family as the main care responsibility bearer and the in-family care model preserving Confucian filial piety, allowing older adults to continue living at home, with the government as the last resort for failed family care [27]. Taiwan's highly marketized foreign caregiver policy represents a neo-liberal aspect [28]. Despite the government's recent push for the Long-term Care 2.0 system, foreign caregivers remain the main providers. The reasons can be summarized as follows:

Insufficient Care Service Personnel

Current long-term care personnel include caregivers, social workers, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and care managers, with caregivers being the primary workforce. The shortage of care personnel has long been an important issue. Although Taiwan has been dedicated to cultivating care personnel, the gap persists. For example, data show that from 2009 to 2016, Taiwan trained 110,000 caregivers, but the retention rate from 2003 to 2014 was only 26%. Data also indicate that the shortage of caregivers in Taiwan in 2017 ranged from 4,950 to 26,409 [29]. Thus, with an increase in long-term care demand, the formal service system’s care personnel cannot meet the corresponding service capacity. Therefore, families with long-term care needs, aside from relying on informal care systems (which are also declining due to changing family structures), mainly hire foreign caregivers to meet care demands.

Limitations of the Formal Service System

Although Long-term Care 2.0 aims to construct an affordable, universal, and high-quality care service system, there are still many limitations for users. Wang [30] pointed out that for those in need of long-term care, current home services not only fail to provide sufficient subsidized service hours but also involve long waiting times and lack of 24-hour care services. These are major reasons why people hesitate to use home care services. Furthermore, current home care services have many restrictions and do not necessarily meet all care needs, whereas foreign caregivers can provide 24-hour care [31]. Thus, when economic conditions permit, the public often opts for foreign caregivers.

Advocacy and Internalization of Family Values

Social policy reflects the government's ideology and views on specific issues. Taiwan's 2011 "Social Welfare Policy Program" mentions "strengthening intergenerational exchange, advocating family values, encouraging generational inheritance, and creating an elderly-friendly and intergenerationally integrated society." This advocacy of family values suggests that the government often views care services as the responsibility of individual families within the framework of filial piety rather than a public affair. This ideology is specifically reflected in the hiring model of foreign caregivers. In contrast, Japan exhibits a different scenario. Owing to the government's long-term investment in formal care services, traditional filial piety concepts have gradually declined and have been replaced by the enhancement of social support concepts. Li [32] found that since Japan introduced a series of formal long-term care policies in the 1970s, although older adults still hold the concept of filial support, actual behaviors have changed from traditional filial practices. For example, Arai and Zarit [33] found that the proportion of people who believed that care should be a shared social responsibility increased from 12.4% to 22.8%, and those who believed it should be entirely borne by society increased from 3.7% to 6.2%. Thus, as Japan’s policy slogan "from family care to social care" indicates, years of expanding the formal care system have allowed Japan to gradually shift from the Confucian cultural emphasis on family care to a social care concept, where the responsibility for older adult care shifts from the family to the state society3.

From the above analysis, existing literature consistently points out that in Taiwan's long-term care services, the family plays the primary role, with the market emerging recently. Although the government has been actively promoting Long-term Care 2.0 services, its reach remains relatively limited. From another point of view, the different sectors should support and collaborate through cross-departmental division mechanisms to meet the needs of older adults. Thus, future research will focus on how to strengthen the interaction, cooperation, and division of labor among different sectors through relevant mechanisms.

Family and Population Structure and Economic Status in Dapi Township, Yunlin County, and Xinkang Township, Chiayi County

Population Structure

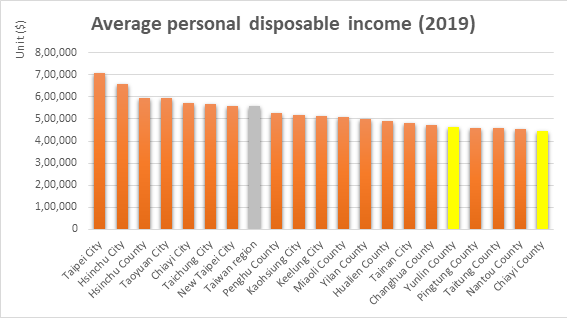

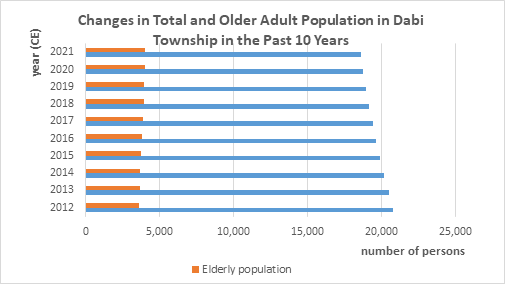

Data from the past decade (using yearly March figures) show a declining population trend in Dapi Township. The aging population (those aged ≥65 years) has been on the rise. Due to these factors, the level of aging has intensified, and by 2017, the township had entered an ultra-aged society. As of March 2021, the older adult population proportion reached approximately 22% (see Figure 5-1).

Figure5-1: Trends in Total Population and Older Adult Population in Dabi Township, Yunlin County Over the Past 10 Years.

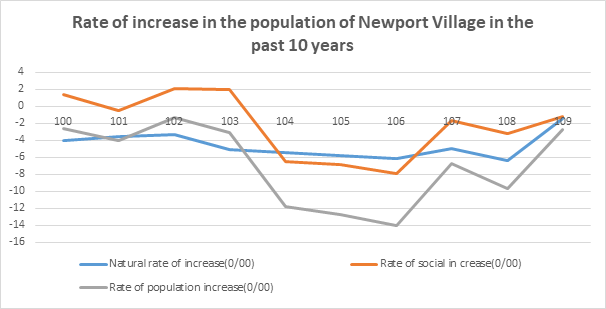

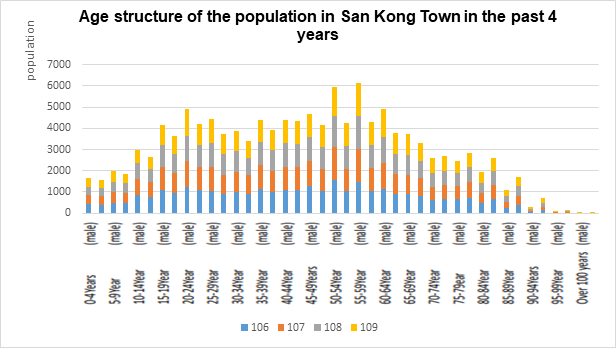

Similarly, Xinkang Township has faced significant population loss and increasing aging trends. Figure 5-2 shows that the natural and social increase rates of the population have been decreasing over the past decade (2011–2020), with a rebound in 2018; however, the population increase rate remained negative in 2020. Figure 5-3 shows that, in the past 4 years (2017–2020), the proportion of the older adult population significantly exceeded that of the underage population. As of April 2021, the older adult population proportion was about 22%.

Figure 5-3: Age Structure of the Population in Xinguang Township, Chiayi County in the Last 4 Years.

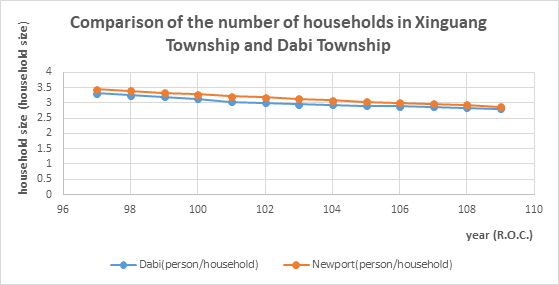

Family Structure

Figure 5-4 indicates that in 2008, both Dapi and Xinkang Townships had an average household size of more than three people. By 2013, the average household size in Dapi Township had decreased to three people, and Xinkang Township also reduced this number to three people by 2017. Subsequently, the household size in both townships has continued to shrink to below three people, resulting in smaller households. Combined with the aging population analysis, it can be inferred that many households are now single or double older adult households due to aging.

Figure 5-4: Comparison of the Number of Households in Dabi Township, Yunlin County, and Xingang Township, Chiayi County.

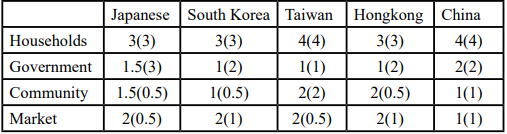

Public Payment Capacity (Disposable Household Income)

Comparing the industrial structures in Yunlin and Chiayi counties, agriculture holds a crucial position (see Table 5-1). The population density in Yunlin County is about half that of Chiayi County, but its agricultural output is more than 1.8 times higher, and its agricultural land area is two times greater than that of Chiayi County. The development of the agricultural sector is reflected in economic development. Figure 5-5 shows that the average disposable income per person in both Yunlin County and Chiayi County is lower than the average of 20 cities and counties in Taiwan (excluding Kinmen and Matsu): Yunlin County ranks 16th, and Chiayi County ranks 20th. In terms of household income, Figure 5-6 indicates that Yunlin County ranks 17th, with Chiayi County still at the bottom. Both counties are below the average value of the 20 cities and counties. Further analysis of household economic conditions shows that the ratio of low-income households in Yunlin County is 2.28%, ranking 4th among the 22 counties and cities nationwide. Chiayi County's ratio is 1.21%, ranking 18th, which is significantly lower than that of Yunlin County, although the number of low-income households has been rapidly increasing recently. The ratio of low-income households in Dapi Township, Yunlin County, is about 2.4%, ranking 9th among the 20 townships in the county and 124th among the 368 townships nationwide (about the top third). In Xinkang Township, Chiayi County, the ratio is about 1%, ranking 17th among the 18 townships in the county and 331st among the 368 administrative districts nationwide, indicating a low ratio both in the county and nation wide.

Long-Term Care Resource Allocation in Dapi Township, Yunlin County, and Xinkang Township, Chiayi County

Cross-Sector Long-Term Care Resource Allocation

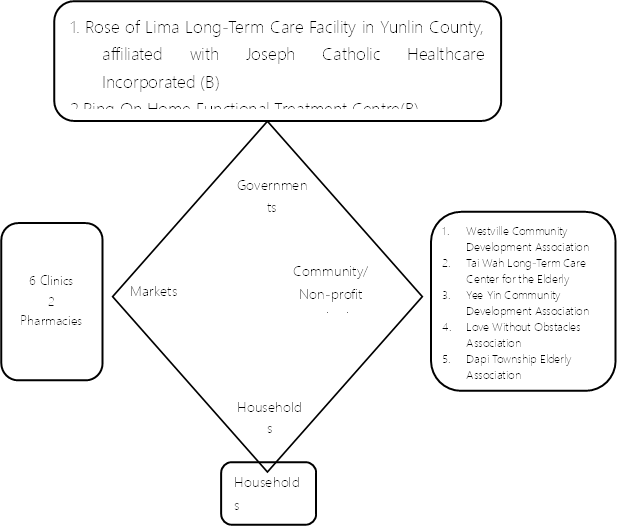

To understand the resources in these areas, we used the care diamond framework to inventory the cross-sector long-term care resources in Dapi Township, Yunlin County, and Xinkang Township, Chiayi County. For Dapi Township, Yunlin County, the national sector includes both 2B and 2C long-term care units. In the market sector, there are six clinics and two pharmacies, including Shangde Clinic, Jiang Bingran Clinic, Liuhe Dental Clinic, Xie Dental Clinic, Dazhong Chinese Medicine Clinic, Liu Guanwei Chinese Medicine Clinic, Shangcheng Pharmacy, and Maoyun Pharmacy. In the community/non-profit sector, there are the Xizhen Community Development Association, Dahua Elderly Long-Term Care Center, Yiran Community Development Association (Elderly Lunch), Ai Wu Ai Association, and Dapi Township Elderly Association, as shown in Figure 6-1.

Figure 6-7: Allocation of Long-Term Care Resources in Dapi Township, Yunlin County— Care Diamond Framework.

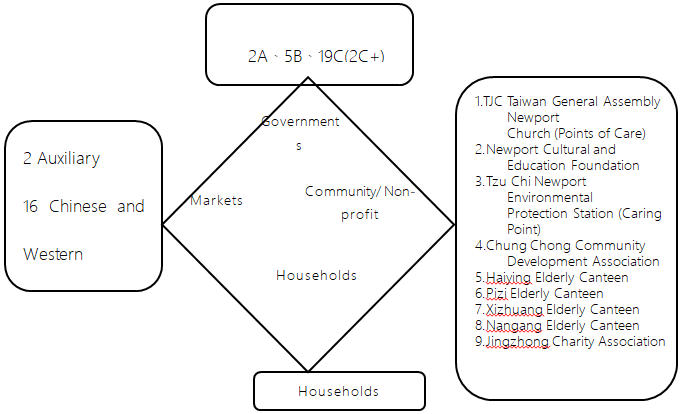

For Xinkang Township, Chiayi County, the national sector incorporates 2A, 5B, and 19C (2C+) units, including Chiayi Christian Hospital (A), Quanan Pharmacy (A, C), Xinkang Township Health Center (B, C; also a service point for Chiayi County Assistive Device Resource Center), Beian Community Long-Term Care Institution (B), Ri'an Day Care Center (B), Shangyi Auto Repair Shop (B), Fulong Long-Term Care Development Association (B, C), Beilun Village Office (C), Beilun Community Alley Long-Term Care Station (C), Anhe Village Community Development Association (C), Caigong Village Community Development Association (C), Gonghe Village Dingcaiyuan Development Association (C), Datang Village Community Development Association (C), Beilun Village Community Development Association (C), Bantou Village Community Development Association (C), Gumin Industry Promotion Association (C), Gumin Village Community Development Association (C), Fuyuan Service Association (C), Chiayi County Xinkang Township Elderly Association (C), Chiayi County Hearing and Multiple Disabilities Coordination Association (C), Chiayi County Xinkang Township Xinyuan Community Development Association (C), Yangming Hospital Affiliated Nursing Home (C), and Gongle Home Nursing (Haiying Village Activity Center) (C). In the market sector, there are two assistive device stores, 16 Chinese and Western medicine clinics, and six pharmacies. In the community/ non-profit sector, there are relevant civil organizations providing services, including True Jesus Church Taiwan General Assembly Xinkang Church (care point), Tzu Chi Xinkang Environmental Station (care point), and Zhongzhuang Community Development Association (care point), as shown in Figure 4-8.

Figure 6-1: Inventory of Long-Term Care Resources in Xinkang Township, Chiayi County— Care Diamond Framework.

Current Status of Market Long-Term Care Resources (Foreign Care Workers)

As mentioned earlier, despite the recent expansion of Long-Term Care 2.0 services in Taiwan, the number of foreign care workers has continued to rise, thus becoming the primary model for long-term care services. What follows is an analysis of the number of foreign care workers in Dapi Township, Yunlin County, and Xinkang Township, Chiayi County, to understand the basic long-term care demand satisfaction model in these two townships.

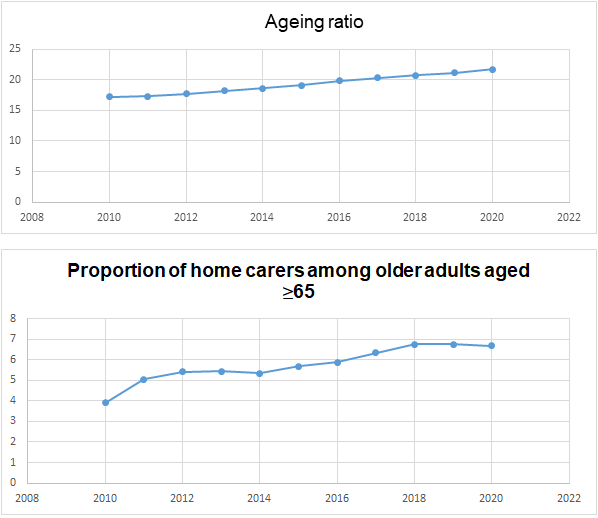

Dapi Township, Yunlin County: Between 2010 and 2020, the proportion of older adults and foreign care workers, as shown in Figure 6-2, reveals that with an increase in the proportion of the aging population, the use of foreign care workers also rises, from 3.91% in 2010 to 6.7% in 2020.

Figure 6-2: Aging Population (Top) and the Proportion of Foreign Care Workers Among Older Adults (≥65 Years) in Dapi Township, Yunlin County (Bottom).

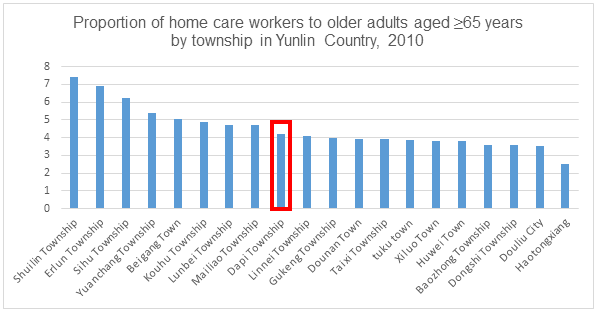

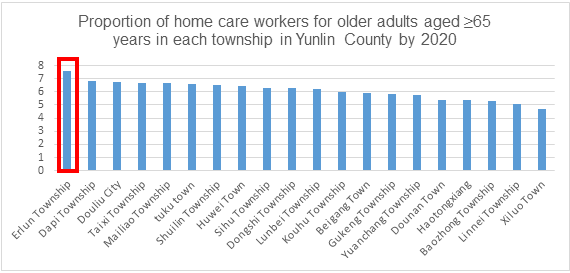

In addition, when examining the proportion of older adults (≥65 years) with family care workers across various townships in Yunlin County, it becomes evident that Dapi Township's reliance on foreign care workers has increased over the years. In 2010, Dapi Township ranked 9th out of 18 townships with a proportion of 4.18%. By 2020, it had risen to 2nd place with a proportion of 6.83%. This finding indicates that, as the aging population grows, foreign care workers, who fall under market-based services, are increasingly becoming the preferred choice for older adults and their families in Dapi Township, as shown in Figures 6-3 and 6-4.

Figure 6-3: Proportion of Family Care Workers Among Older Adults (Aged ≥65 Years) in Yunlin County Townships in 2010.

Figure 6-4: Proportion of Family Care Workers Among Older Adults (Aged ≥65 Years) in Yunlin County Townships in 2020.

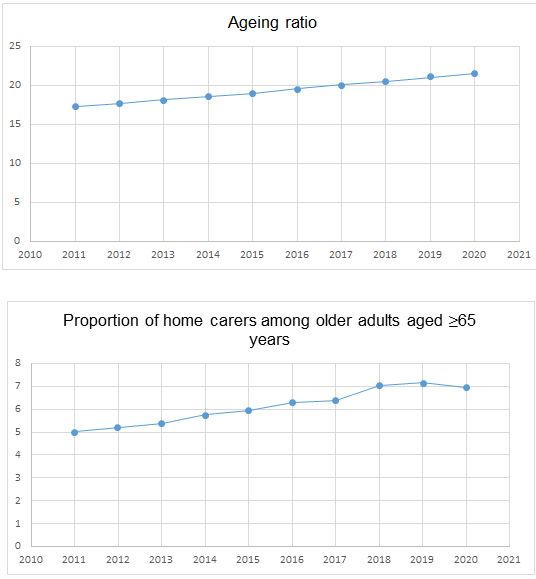

Similarly, in Xinkang Township, Chiayi County, between 2010 and 2020, the proportion of older adults and the use of foreign care workers also increased. The proportion of foreign care workers rose from 5.0% in 2011 to 6.96% in 2020, as shown in Figure 6-5.

Figure 6-5: Aging Population (Top) and the Proportion of Foreign Care Workers Among Older Adults (≥65 Years) in Xinkang Township, Chiayi County (Bottom).

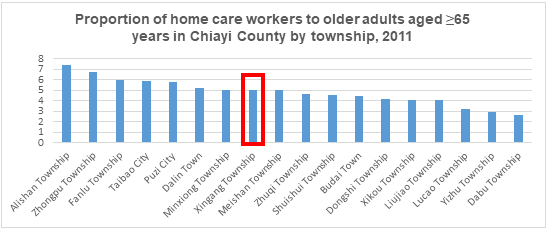

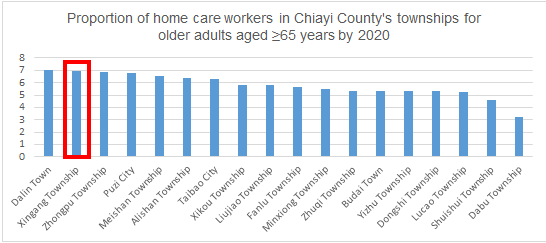

The changes across the 18 townships in Chiayi County clearly show that there is a growing preference for foreign care workers among older adults in Xinkang Township. In 2011, Xinkang Township had a proportion of family care workers among those aged ≥65 years of 5.00%, ranking 8th among all townships. By 2020, this proportion increased to 6.96%, propelling Xinkang Township to 2nd place. This trend also reflects that in Dapi Township, Yunlin County, older adults and their families have been increasingly relying on market-based foreign care workers to meet their long-term care needs, as illustrated in Figures 6-6 and 6-7.

Figure 6-6: Proportion of Family Care Workers Among Older Adults (Aged ≥65 Years) in Chiayi County Townships in 2011.

Figure 6-7: Proportion of Family Care Workers Among Older Adults (Aged ≥65 Years) in Chiayi County Townships in 2020.

From the resource inventory and analysis, the following observations can be made:

Population Structure, Family Type, and Economic Conditions. Both Dapi and Xinkang are typical townships in the Yunlin-Chiayi region, with an aging rate exceeding 22% and experiencing negative population growth. The average household size is below three, indicating a high number of older adults or single older adult households, reflecting a growing demand for long-term care services. The aging population and negative population growth are linked to economic decline, similar to many remote areas lacking sufficient labor for economic activities4. This economic underdevelopment affects the payment capacity of long-term care users. In ultra-aging townships, the high frequency of long-term care services and related out-of-pocket expenses (e.g., taxis) increase the financial burden on households that are already economically strained.

Cross-Sector Long-Term Care Resources. Compared to Dapi Township in Yunlin County, Xinkang Township in Chiayi County has more abundant long-term care resources, including more pharmacies, clinics, and assistive device stores. Additionally, Xinkang Township has a larger number of social welfare organizations and senior meal programs5.

Trends in Foreign Care Workers. Over the past decade, both Dapi and Xinkang townships have increasingly relied on foreign care workers for long-term care services. In terms of the proportion of foreign care workers among older adults (≥65 years), Dapi Township rose from 9th place (4.18%) in 2010 to 2nd place (6.83%) in 2020. Xinkang Township also rose from 8th place (5.00%) in 2010 to 2nd place (6.96%) in 2020. The reliance on foreign care workers has climbed in rural areas due to limited capacity for long-term care services, with the introduction of Long-Term Care 2.0 leading to a higher proportion of foreign care workers.

Analysis and Discussion of Long-Term Care Division

According to a study by Wu et al6. [38] on the distribution of long-term care services in urban and rural areas from 2018 to 2020, a growth trend in the use of long-term care services is evident over this period. This trend also reflects the increasing older adult population in various towns. However, disparities in the utilization of services based on urbanization levels are apparent as well. In highly urbanized and densely populated areas, the use of long-term care services has increased annually, while in rural areas, this use has declined. Coastal areas have seen a gradual increase, but mountainous regions such as Alishan and Dapu have consistently shown low utilization. Furthermore, Dapi Township's use of long-term care services is significantly lower than that of Xingang Township, with considerable variations in usage across different villages in Dapi.

Wu et al. [38] also highlighted two significant features regarding economic capacity and income levels. First, a static inequality was observed, with lower usage rates among middle-to-low-income groups in metropolitan areas. Second, a dynamic inequality emerged over time, with the usage rate among middle-to-low-income groups in more remote areas gradually decreasing, which led to income polarization. Although the government has intervened by providing long-term care resources, income disparities are also reflected in the utilization of these resources. Expenditure on long-term care services shows inequality based on urbanization levels, with higher expenditures evident in more urbanized areas. High-income regions tend to have higher total expenditures on long-term care services. In contrast, Dapi and Xingang Townships have relatively low expenditure levels compared to other townships.

In terms of categories of expenditure, care services (BA code) have the highest number of users. Regardless of the service type, both the number of users and expenditure amounts are concentrated in metropolitan areas, with less usage in more remote regions. Xingang Township’s higher supply of services results in higher utilization rates than Dapi Township. In addition to supply factors, older adult residents in remote areas tend to suppress their daily living needs to reduce the likelihood of using long-term care services. Therefore, it is suggested that the following perspectives be considered:

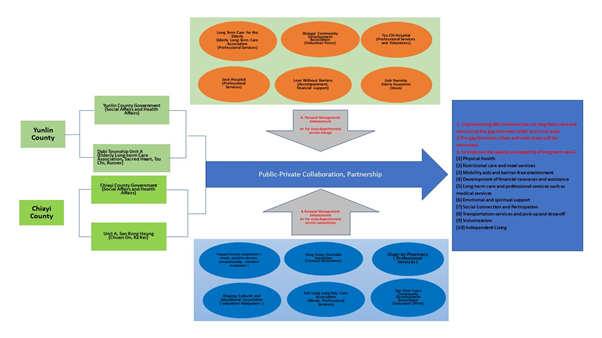

1. Diversification of Departmental Collaboration and Resource Linkage Types

Currently, resource linkage in the A case management service primarily involves formal long-term care resources (e.g., unit B). It is recommended that the types of resource linkages for case management be expanded to include social welfare centers, family caregiver centers, and non-social affairs system resources (e.g., civil affairs, household registration, and police). This expansion, facilitated by training workshops, aims to build a comprehensive service network that spans formal/informal, social/non-social systems, and public/ private sectors in the community (see Figure 7-1).

2. Increased Involvement of Grassroots Government Agencies

Beyond the existing connections with the Health Bureau (Long-Term Care Center) and health clinics, it is essential to include local offices (social affairs divisions) and the social bureaus (e.g., family caregiver centers). This integration will enable cross-departmental administrative meetings to link resources and meet local long-term care needs.

3. Balance and Fairness in Departmental Collaboration

Using the care diamond as a cross-departmental analytical concept, this study aimed to clarify the roles and responsibilities of the government, market, family, and community in long-term care services. Despite the increasing involvement of the state in long-term care governance due to an aging population, the state prefers to assume responsibility through subsidies and funding rather than providing services directly. Furthermore, the study noted a significant increase in the proportion of older adult residents with foreign caregivers in Dapi and Xingang Townships, which reflects a reliance on market-driven foreign caregivers to meet long-term care needs.

The analysis of the diamond model of long-term care services shows that when two regions focus on the development of family and market aspects, there is an expectation that the needs of older adults can be met through the connection of informal community resources, in addition to the formal network of long-term care services. This study suggests that more diverse channels and forms should be utilized to achieve this goal. Consequently, it argues that the current establishment of a long-term care safety net lacks an integrated mechanism7.

Figure 6-8: Diagram of Integrated Long-term Care Services under the Empowerment of Public–Private Collaboration in a Case Management

Furthermore, from the perspective of welfare development, the application of public–private partnerships and collaborations in Taiwan's long-term care system appears similar to the concept proposed by Kuhnle and Selle [20] of moving from decentralized autonomy to integrated dependency. In the Long-Term Care 1.0 phase, the government initially allowed voluntary organizations to operate independently, with minimal close relationships. However, with the advent of Long-Term Care 2.0, the government actively integrated non-profit organizations into its long-term care service network. Many long-term care service units were established to undertake government programs, and the government used evaluations and performance management to achieve policy goals. This trend, restrained by the framework of outsourced contracts, lacks the flexibility to meet community care needs. The challenge lies in maintaining the autonomy and mission of non-profit organizations while transitioning from decentralized autonomy to integrated dependency to decentralized autonomy to integrated self-reliance, ensuring sustainable development in the future. Overall, based on the aforementioned analysis, this study suggests the following:

I. Adopting the public sector implementation model, collaborating with local governments and Unit A to plan and enhance on-the job training for A case-manager. The goal is to transform A into A+ with a PIC spirit, improving resource utilization and feasible strategies.

II. Training local personnel with resource integration and coordination skills. These individuals must understand how to link and utilize public and private long-term care resources to reduce the likelihood of the liposuction effect due to a lack of resource integration. At the township level, they should connect and integrate formal and informal services, including long-term care, medical care, community volunteers, and various life resources (such as financial advice or life skills) based on the actual needs of older adults.

III. Increasing the number of female labor participation. As former London School of Economics President Minouche Shafik stated, a well-designed long-term care system can provide more employment opportunities for women in non-profit organizations. Continued employment allows women to participate in social insurance and become taxpayers, ensuring their future economic security and contribution to older adult care [39].

IV. Advocating for the concept of co-production, where care recipients can also become caregivers. Additionally, the idea of symbiotic communities promoting intergenerational mutual support should be integrated into local care networks. This approach can maximize and effectively utilize community care resources, thus enhancing the potential for social innovation.

Summarizing the conclusions of this study, the implementation of public-private collaboration has a considerable impact on the establishment of a community integrated care system, and the more suburban areas are in cities, the more likely they are to be ignored by the formal service delivery system, especially if there is a lack of a linking mechanism between the public and private sectors. This compromises the effectiveness and efficiency of service delivery, causing service users to choose other ways to meet their needs. Informal care resources hidden in the community are an aspect that government departments cannot ignore.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

National Development Council Population Estimate Inquiry System (2021). View

Apple Daily. (2020). During the Warring States Period, when reporting was excessive, the Ministry of Health and Welfare had to amend the law to increase penalties.

United Daily News (2020). Is long-term care really a good business? The number of housing units has tripled, and people are being robbed, causing chaos.

Wu, X. (2017). New opportunities for my country's long-term care policy. Journal of Long-Term Care, 21(1), 1–7.

United Daily News (2021). A housekeeper in Changzhao is in trouble. View

Wu, M., Liu, H., & Ou, Z. (2018). Analysis of the establishment of community care integration system from the perspective of co-production—taking Dingcaiyuan Community as an example, Taiwan Journal of Community Work and Community Research, 8(3), 123–160.

Xu, J., Liao, W., Zhou, X., & Huang, Z. (2019). Challenges and countermeasures of long-term care stations in alley—A preliminary discussion on health promotion taking root in the community. Journal of Health Promotion and Health Education, 43, 105–131.

Lloyd, J., & Wait, S. (2005). Integrated care: A guide for policymakers. WHO Consultant on Aging and Life Course. View

World Health Organization. (2002). Lessons for long-term care policy.View

Evashwick, C. (2005). The continuum of long-term care. Cengage Learning.View

Chen, F. (2018). Comparison of management policies for foreign caregivers—taking Japan, Finland and China as examples. Edited by Wang Lilong, Far east white paper series— foreign caregiver labor rights under the demand for long-term care. Far East Group—Mr. Xu Yuanzhi Memorial Foundation.

Li, P., & Zheng, Q. (2019 ). Experiences and challenges of community integrated care in Taiwan: Taking health care professional services as an example. Journal of Social Policy and Social Work, 23(2), 179–223.

Johnson, M. (1987). The body in the mind: The bodily basis of meaning, imagination, and reason. University of Chicago Press. View

Huang, Y. (2004). "From "full control agency" to "best value"— context and reflections on the development of community care in the UK. Community Development Quarterly, 106, 308–330.

Evers, A., Pijl, M.,& Ungerson, C. (1994). Payments for care. Ashgate Publishing. View

Huang, Z. L. (2018). Reflections on the reconstruction of long-sterm care policies in European countries: Theoretical dialectics between market, family, and community. Taiwan Journal of Community Work and Community Research, 8(3), 99–122.

Fraser, N. (1994). After the family wage: Gender equity and the welfare state. government and voluntary organizations in Norway in Ware, Alan & Robert E. Goodin (eds.), Needs and welfare. Ch. 9. Sage.View

Considine, M., Lewis, J., O'Sullivan, S. & Sol, E. (2015). Getting welfare to work: Street-level governance in Australia, the UK, and the Netherlands (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. View

Ye, C., & Gu Y. (2022). The connection between social policy and the social work profession: the case of the UK. Journal of Social Work and Social Welfare, 1, 81–112.

Kuhnle, S., & Selle, P. (1990). Meeting needs in a welfare state: Relations between

Huang, Y., & Zhuang, L. (2020). Social work management, 4th Ed. Futaba.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Polity.View

Ochiai, E. (2009). Care diamonds and welfare regimes in east and south-east Asian societies: Bridging family and welfare sociology. International Journal of Japanese Sociology, 18, 60–78. View

Chan, R. K. H., Soma, N., & Yamashita, J. (2011). Care regimes and responses: East Asian experiences compared. Journal of Comparative Social Welfare, 27(2), 175–186. View

Zhou, Y. (2008). Reexamining the welfare system in east Asia— Analysis of long-term care policies in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. Institute of Social Welfare, National Chung Cheng University.

Liang, L., & Su, Y. (2018). Foreign home care workers— Legislative controversies in the domestic service law. In Wang Lilong, editor, Far East white paper series—foreign caregiver labor rights under long-term care needs, pp. 37–52. Far East Group—Mr. Xu Yuanzhi Memorial Foundation.

Chen, L., Zhou, Y., Yang, M., Weng, R., Sun, W., Chen J., Liu, Z., Huang, S., & Zeng, X. (2018). Personal care therapist's experience in integrated care services in the community. Beijing Medical Journal, 15(1), 21–27.

Ogawa, R. (2017). Transformation of care in east Asia: Migration and emerging regional care chain. Paper presented at the Innovation and Sustainability Third Transforming Care Conference, Milan, Italy. Political Theory, 22(4), 591–618. View

Ministry of Health and Welfare (2016). Ten-year Long-term Care Plan 2.0. View

Wang, M. (2018). The intersection between care system and foreign care work policies—Taking Taiwan as an example. In Wang Lilong, editor, Far East white paper series—Foreign caregiver labor rights under the demand for long-term care, pp. 103–128. Far East Group—Mr. Xu Yuanzhi Memorial Foundation. View

Li, Y., & He, L. (2018). The impact of long-term care policy on foreign caregivers. In Wang Lilong, editor, Far East white paper series-foreign caregiver labor rights under the demand for long-term care, pp. 53–78. Far East Group—Mr. Xu Yuanzhi Memorial Foundation.

Li, P. (2017). Discussion on Japan's nursing care insurance system under the changes of population, economy and family structure. Journal of Jingyi Humanities and Social Sciences, 11(1), 73–118.

Arai, Y., & Zarit, S. H. (2011). Exploring strategies to alleviate caregiver burden: Effects of the National Long-Term Care insurance scheme in Japan. View

Yunlin County Dounan Household Registration Office (2021). The number of neighbors in the village, the number of people by gender and age. View

Local Creation Database (2021). Xingang Township, Chiayi County, and Dapi Township, Yunlin County.

Yunlin County Household Registration Information Network (2021). Gender age population. View

Chiayi County Government Accounting and Accounting Office. (2021). Demographic indicators.

Wu, M., Hao, F., Li, M., Chen, K., Zhou, Y., & Liu, H. (2021). Research and models on strengthening cross-department division of labor and social welfare integration mechanism— taking long-term care services as an example. Research project commissioned by the National Heath Research Institutes.

Xu, R. (2023). A New Social Contract—from cradle to grave, what we owe each other—a New Social Contract. Star Publishing.