Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-132

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100132Research Article

The Impact of Supervision Function and the Development of New Social Work Professional Knowledge and Ability on Service Performance~ Taking the Case Management Service for Individuals with Disabilities in Taiwan A City as an Example

Mei Jung Liang

Assistant Professor, Department of Social Work, National Quemoy University, Taiwan.

Corresponding Author Details: Mei Jung Liang, Assistant Professor, Department of Social Work, National Quemoy University, Taiwan.

Received date: 06th January, 2025

Accepted date: 30th January, 2025

Published date: 01st February, 2025

Citation: Liang, M. J., (2025). The Impact of Supervision Function and the Development of New Social Work Professional Knowledge and Ability on Service Performance~ Taking the Case Management Service for Individuals with Disabilities in Taiwan A City as an Example. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(1): 132.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Supervisors play a crucial role in social work services across various fields. This study examines their role in case management services for individuals with disabilities, focusing on how supervisors guide new social workers and the impact of supervisory functions on professional development and service effectiveness.

Research Objectives: The study aims to explore the dynamics between supervisors and new social workers, particularly in terms of supervisory approaches and their effects on service delivery and professional growth.

Research Methods: A focus group discussion was conducted, involving four supervisors and nine social workers, each with one year of experience. The transcripts from these discussions were analyzed and compared to identify key themes and insights.

Research Results: Findings indicate that while both supervisors and new social workers value emotional stability and mediation skills, supervisors tend to adopt a goal-oriented approach, emphasizing administrative and professional guidance with less focus on emotional support. Conversely, new social workers desire more comprehensive support and improved communication. Existing training programs for new social workers are often formalized and mentorship-based, relying heavily on supervisors’ past experiences. However, these programs frequently fail to address the diverse learning needs of new employees, leading them to depend on a trial-and-error approach. Both groups acknowledge that it takes approximately six months for new social workers to adapt to their roles, but internal challenges, such as skill gaps, and external pressures, like high caseloads, impede service efficiency.

Recommendations: To address these challenges, the study recommends providing targeted training and support for novice supervisors, reassessing caseloads to balance service quality and staff safety, establishing support mechanisms for supervisors to manage stress, and creating flexible training modules that emphasize practical application and the development of diverse topics.

Research Novelty: This study highlights the gap between current supervisory practices and the needs of new social workers in disability case management services. By identifying specific areas for improvement, it offers actionable insights to enhance professional development and service effectiveness in this field.

Foreword

As the service targets and demographic structure become more and more complex with the changes of the times, supervision work will also become more difficult to perform. However, supervisors play an extremely important role in the professional development of social workers. They not only provide high-quality services, but also are the souls who assist social workers in achieving professional growth and improving the social work profession [1]. Therefore, the supervision mechanism is established to ensure the quality of professional services and the rights and responsibilities of service recipients. A positive and systematic supervision process can help social workers to enhance their recognition of their professional mission, improve their professional skills and knowledge, ensure the quality of service delivery, and help service recipients improve their current situation, thereby achieving mission and purpose of the organization. On the contrary, failure to perform supervisory functions will cause social workers to have doubts about the quality and effectiveness of the services they provide, affecting the rights and interests of service recipients and even the reputation of the institution. In general, social work supervision refers to the regular and ongoing guidance provided by an experienced and knowledgeable social worker assigned by the organization to supervise newer or less experienced staff, as well as those working on specific projects, through direct teaching or mentoring. This is one of the key responsibilities of the supervisor.

According to the definition of Article 5 of the People with Disabilities Rights Protection Act (hereinafter referred to as the Disabilities Rights Act), persons with disabilities are those who, due to impairments or deficiencies in the structure or function of their physical systems, experience significant deviations or loss that affect their ability to engage in activities and participate in social life. They are certified by a professional team consisting of medical, social work, special education, and vocational counseling personnel, and hold a certificate of disability. Services for persons with disabilities were further integrated into legislation with the introduction of "case management" in the 1997 Protection of Persons with Disabilities Act. Following this, case management service centers for persons with disabilities were established across Taiwan. After the amendment of the Disabilities Rights Act in 2007, the term "case management services" was removed, and services for persons with disabilities began to be offered under various names and content across Taiwan. However, to this day, case management services for persons with disabilities (hereinafter referred to as "disability case management") remain one of the key service components.

In Taiwan, supervision within disability services presents unique challenges compared to other social work fields. Disability case management often involves coordinating a wide array of services, including welfare consultation, career transition services, community resource connections, and dual elderly services for families of persons with disabilities. This multifaceted approach requires supervisors to possess specialized knowledge and skills to effectively guide social workers in addressing the complex needs of individuals with disabilities. In contrast, supervision in other social work domains may focus on more specific areas, such as medical social work, mental health, child and family services, or services for the elderly, each with its own set of challenges and supervisory requirements.

Regarding retention rates among social workers, effective supervision plays a pivotal role. Studies have shown that supervisors who provide adequate support, such as guidance in case management and assistance in resolving service challenges, can enhance job satisfaction and commitment among social workers. This supportive supervisory approach has been linked to higher retention rates, as social workers feel more valued and competent in their roles [2]. Conversely, a lack of support and guidance can lead to increased turnover, negatively impacting service continuity and organizational reputation.

In summary, supervision in Taiwan’s disability services is distinct due to the comprehensive and integrative nature of the work, necessitating specialized supervisory approaches. Moreover, effective supervision is crucial in promoting higher retention rates among social workers, thereby ensuring the delivery of quality services to individuals with disabilities.

In A city, the execution of this service is carried out by public agencies, which are responsible for reporting, screening, and assigning cases to different regions. The subsequent services are then outsourced to private organizations. The services provided by the private agencies commissioned by the city include welfare consultation, career transition services, case management services, community resource connections, resource development, and the newly added dual elderly services for families of persons with disabilities. Given the various life aspects and lifecycle needs of persons with disabilities, the work for any disability case management worker is a challenge. Therefore, the role of supervision becomes crucial. More importantly, social work staff generally have a high turnover rate [3]. Disability case management work is heavy and highly challenging, often affected by insufficient resources or overly complex issues, leading to instability in the workforce. As a result, disability case management supervisors often face the dilemma of having to train new social workers (hereafter referred to as "new social workers"). In this cycle, the researchers are concerned with how supervisors, the internal organization and the environment cultivate the professional knowledge and skills of new social workers, and whether this affect service effectiveness.

In the case management service of a city studied in this article, there are 4 supervisors and 21 social workers. On average, 1 supervisor leads 4-6 social workers, which is a reasonable range. However, among the 21 social workers, the length of service varies. There are 11 people who have been employed within one year, accounting for 52% of the total, and 5 of them have 2 years of experience. For supervisors, the training phase for new employees is a very stressful time for them. This has also aroused the curiosity of the city's competent authorities and researchers, hoping to understand the current situation of supervisors of disabled individuals in leading the professional knowledge and skills of new social workers, and whether adjustments and changes can be made to reduce turnover and improve service efficiency.

Literature Review

Disability Case Management Services and the Current Status of Services in Taiwan

Physical and mental disabilities can occur at any stage of an individual's life, resulting in a variety of needs such as daily care, education, employment, and medical treatment, with the greatest impact on economically disadvantaged families. Additionally, the diverse types of physical and mental disabilities, result in multiple characteristics and needs, covering physical, psychological, and social aspects; in addition, the division of domestic administrative units affects service provision, and since it is not a single point of contact, resources are fragmented. Therefore, when service providers need to assist people with disabilities who face multiple needs or problems and require the intervention and assistance of multiple resources, adopting a case management service model is the most suitable approach. Case management is a service process that coordinates, integrates, and jointly plans with different welfare resources to address the diverse needs of cases. Case management is a service process that coordinates, integrates, and jointly plans with different welfare resources to address the diverse needs of cases [4,5].

Since the establishment of case management services for people with disabilities in Taiwan, most of them have been managed by private organizations commissioned by the government. Although the term "case management" was removed from the regulations after the amendment of the Disabilities Rights Act in 2007, local governments across Taiwan have expanded the necessary resources outlined in the regulations and renamed the service programs [6,7]. As a result, the names and contents of the services vary between different local governments, but case management services remain a key component. The target service users are persons with disabilities aged 7 to under 65. The services include the establishment of a disability reporting system and the integration of formal and informal community resources through a case management service model. Individualized Service Plans (ISPs) are used to assist persons with disabilities and their families in accessing the resources they need, enabling them to overcome life difficulties and solve problems through resource utilization and empowerment.

The resources connected include comprehensive and integrated services such as medical treatment, education, hygiene, employment, economics, psychological counseling, emotional support, legal consultation, etc. Furthermore, due to limited public sector resources and the limited capacity of non-profit organizations, persons with disabilities and their families often find themselves in a state of resource scarcity [8].

Therefore, when the government commissions services, it incorporates a wide range of services for persons with disabilities, including welfare consultation, career transition, follow-up care for stable placement after disability protection, re-evaluation of disabilities, case management services (including medical and psychological rehabilitation, school education, work assistance, institutional care, economic assistance, housing services, assistive devices, family support, advocacy for rights, etc.), as well as emphasizing community resource connection, development of informal resources, and services for families of individuals with intellectual disabilities, among other preventive services.

Supervision role functions and responsibilities

Supervision, regardless of the field, is regarded as essential and significantly impacts practitioners while fostering professional development [9]. The supervisory relationship is a bidirectional interactive process where organizations grant supervisors authority to guide one or more individuals of varying experience levels. This involves teaching or fostering their work-related knowledge and skills, enhancing their professional techniques, establishing correct work attitudes, or fostering positive interpersonal relationships. These efforts aim to bring about behavioral changes in supervisees. Simultaneously, supervisors engage with supervisees of diverse characteristics, adapting their supervisory approach accordingly. When both supervisors and the supervisees maintain a good relationship, it enhances supervision effectiveness and the overall efficiency of practical operations [9,10]. Furthermore, the importance of supervision extends beyond supporting the professional growth of supervisees. It also includes safeguarding the rights of service recipients to high-quality services, upholding organizational prestige and service quality, and achieving professional recognition in society [11-13].

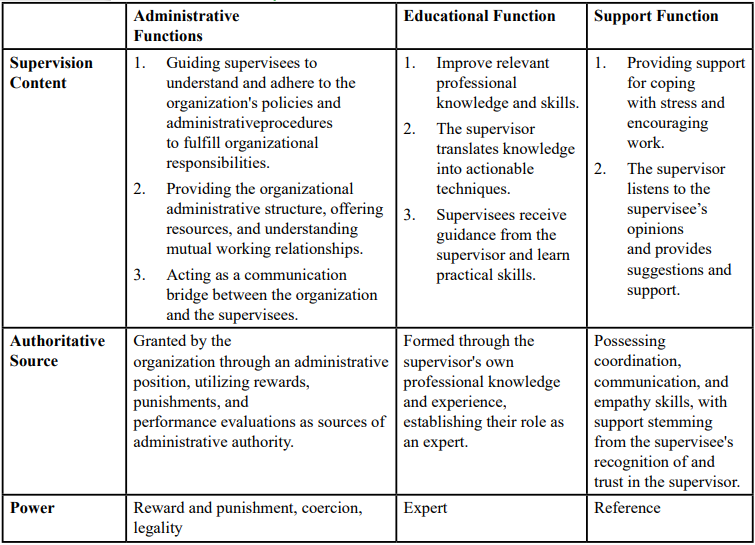

Based on Kadushin's [14] classification of supervisory functions, they are divided into three categories: administrative, educational, and supportive functions [14]. An introduction to these three main supervisory functions and their sources of authority is presented in the table below:

As shown in Table 1, French and Raven [15] categorized power into five types: reward, coercive, legitimate, referent, and expert power. Reward, coercive, and legitimate power come from organizational authorization, with the supervisor being viewed as an administrative manager. Referent and expert power stems from the supervisor's personal and professional identity, where the supervisor demonstrates personal qualities and professional capabilities. Therefore, the supervisory relationship also involves a reciprocal power interaction, which influences the supervisee's professional performance and the impact on service effectiveness.

Social work practice emphasizes the importance of supervision. The field of disability case management is inherently diverse and complex, and with the increasingly complicated policy development trends in disability case management, the role of supervisors becomes even more crucial. Supervisors play a key role in empowering disability case managers. However, being a supervisor comes with different stages. Novice supervisors face challenges in transitioning and adapting to career roles, and supervisors with varying years of experience progress through different stages. Typically, it takes over five years to become a mature supervisor. Many supervisors also lack professional confidence. Therefore, despite becoming a supervisor, it is recommended that different training models and course focus be implemented at different stages. Viewing the enhancement of supervisor education as part of the job would be more beneficial [16-18].

The challenges faced by supervisors of disability case management services in guiding new social workers.

The foundation of professional service effectiveness lies in the maturity of social workers' professional knowledge. Social workers rely on professional knowledge to define their roles, equip themselves with the necessary professional competencies, and provide services. This process is not limited to the training received in schools; practical work organizations are also responsible for assisting social workers in enhancing their professional knowledge to improve service effectiveness. These further highlights that developing professional competencies in new social workers is necessary for improving service effectiveness [19,20].

In 2017, Zheng Su-Fen and Zheng Chi-Wei conducted a study on the self-experience of new disability case managers in establishing service competencies during career transitions. Their findings highlighted several points. First, new social workers often enter the field of disability case management through familiar networks, such as introductions from classmates or senior peers. Second, due to individual personality differences, new social workers often experience challenges, which require support. Third, when first encountering disability case management, there is an expectation that professional competencies will be cultivated through assistance from peers or supervisors in every aspect of the work. Lastly, after accumulating experience, they begin to identify with the work and gain a better grasp of its dynamics [21].

The aforementioned study also pointed out the difficulties faced by new social workers in various professional competency trainings. These challenges include the geographical divisions of different regions, which prevent case assignments from being tailored to the new social worker's needs, and do not always allow for a gradual transition from simple cases to more complex ones. Secondly, due to shortages in organizational personnel or work planning, new social workers may not have supervisors or experienced social workers to accompany them on home visits and guide them in a learning by-doing approach. Third, because disability case management emphasizes the construction of resource networks, new social workers may not be familiar with available resources, and can only become familiar with and understand them gradually through cases. This results in suboptimal service effectiveness and affects the consistency of service design in disability case management. Finally, interpersonal interactions in the work environment require support from supervisors and peers [21].

As seen above, for new social workers in disability case management, in addition to the training received in school, once they enter the organization, they largely rely on supervisors and peers to provide service knowledge. In particular, supervisors, based on their characteristics, arrange suitable individual supervisory models and training, gradually enabling new social workers to work independently and improve service effectiveness. However, given the diversity of service recipients and content in this field, there is an expectation that disability case management social workers must possess the ability to address various disabilities, multiple needs, and a variety of community resources. In practice, however, high turnover rates among disability case managers are observed, and supervisors often need to repeatedly train new staff. With the complex demands of the job and the aforementioned expectations from new social workers regarding training, this becomes both a visible and invisible challenge for supervisors in disability case management.

Research methods

This study adopted the focus group method to collect qualitative data. The goal is to discuss relevant experiences, emotions, attitudes and opinions on the topic in an unrestricted environment to promote the diversity of data; through the interaction between researchers and respondents, the questions can be clarified and the respondents’ inner thoughts can be confirmed. Real feelings and behavioral cognition [22,23]. This study was conducted by the competent authority of City A to invite 4 supervisors and 11 new social workers who had been employed for less than 1 year to the Case Management Center for Persons with Disabilities in City A. The researchers are highly sensitive to ethical issues. Before the focus group, they explain the purpose, content, methods and rights of participating in the research to the participants. If they are willing to accept the research, they will further sign the consent form and basic information to agree to participate. The researchers included 4 supervisors and 9 new social workers.

Based on the years of work experience and research purpose of the disabled person management staff in City A, and to strengthen multi faceted testing, the focus group was divided into two sessions on August 10, 2021. One was a supervision group, including six people including researchers and assistants. The other was for new social workers within one year, including researchers and assistants, a total of 11 people. Each focus group lasted about 2 hours. The research assistants only played the role of recording and observation and were not involved. The entire focus group process was recorded, and after the interview, the original data of the interview process was transcribed into a true and complete transcript, and the data was collated and analyzed. According to Yin [23], qualitative data is conducted in five steps: analysis cycle, unpacking and coding (codes), reorganization and classification, interpretation, and finally connecting the data with each stage to draw conclusions in order to maintain the authenticity of the research.

In the supervisor focus group, the average age of the supervisors was 41 years, with an average of one year of supervisory experience and an average of 12 years of social work experience. All four supervisors had at least a university degree and held social work certification. The interview with the supervisors primarily focused on the competencies they believed disability case managers and themselves as supervisors should possess, their supervisory style, the training they provide to new social workers, and their thoughts on the service effectiveness of new social workers. In the new social worker focus group, there were a total of nine participants, accounting for over 40% of the disability case managers in the city. The average age was 34 years, with an average of six months of experience in disability case management and an average of 9.3 years of social work experience. All nine new social workers had university degrees, and three held social work certifications. The main questions in the interview with new social workers were about the competencies disability case managers should possess, the ideal role supervisors should play, the process from starting the job to becoming proficient, how supervisors conduct training, how they seek help when facing difficulties, and finally, feedback from new social workers on their current service effectiveness.

Discovery and discussion

Based on the two focus group sessions, a total of 13 participants were interviewed to explore the supervisory functions and the service effectiveness of new social workers. The findings revealed three key points: First, the similarities and differences in how different roles perceive the supervisor's role and functions; second, the current situation of how supervisors lead new social workers; and third, the impact of supervisory functions and the professional competencies of new social workers on service effectiveness.

Similarities and differences in how different roles perceive the supervisor's role and functions

(1) Consistency in the importance placed on the supervisor's role

Both supervisors and new social workers agreed on three common perspectives for supervisors in disability case management. First, supervisors should possess positive personality traits, such as the ability to accept challenges, effective communication skills, resilience under pressure, good judgment, and a stable and consistent attitude. Second, emotional management is crucial, which includes being aware of the emotional state of social workers and recognizing that the supervisor's emotional state can impact the supervisory relationship. Third, supervisors should have the ability to connect resources and mediate, such as engaging in discussions and negotiations with resource networks and local governments and serving as a communication bridge between the organization and social workers.

As a supervisor, your personality traits are really important. You must have some communication skills, emotional management, decision-making, stress resistance, and judgment... (Supervisor-3)

I think (the supervisor's) emotional stability is the most important. I think emotional stability is the most important. Even though we work in the same office, it’s like sensing the atmosphere— whether the person is in a good mood or not. Can I talk to them? Can I discuss things with them?

(Social Worker-1)

Another point is that the supervisor can help us when there’s something that needs communication within the organization. They can act as a mediator... they can help us communicate. (Social Worker-7)

(2) Different expectations of the supervisor’s role

There are differences between supervisors and new social workers regarding the role and functions of disability case management supervision. The first difference lies in the direction and approach of supervision. Supervisors believe that they need to provide directional guidance but do not necessarily give immediate answers. They also feel that supervisors should have the ability to conduct multiple evaluations and offer guidance to point out aspects that new social workers might not have noticed. On the other hand, new social workers expect supervisors to provide clear direction and offer more support, avoiding immediately dismissing their thoughts or assessments. They hope for smoother communication, enabling them to translate the supervisor’s experience into their practices, rather than simply following the supervisor's methods.

When discussing with social workers, the goal is for them to benefit from the conversation, learning how to view things from different perspectives, not just being answered immediately. It’s about how to guide them. (Supervisor-2)

What’s different about you compared to the social worker is that you can see different points… especially when working with new social workers, they might only focus on the obvious problems, but as a supervisor, you need to be able to see what’s behind those issues. (Supervisor-3)

I need to have a way of understanding. Understanding the service context, etc., so I can guide you from another perspective, rather than immediately dismissing your approach. (Supervisor-6)

Supervision needs to include both supervision and guidance. You can’t just keep supervising without guiding, or I’ll feel like I have no direction. The most important thing is that you need to provide guidance. (Social Worker- 9)

I think the supervisor shares their experience, and that experience makes me think about how to translate it into my way of working, rather than fully accepting it because everyone has their methods. (Social Worker-5)

The second difference is in the perception of supervisory functions. Most supervisors believe that the majority of their supervisory functions are dedicated to professional education, with at least 20% allocated to providing support. However, from the perspective of new social workers, about one-third of them feel that supervisors primarily focus on administrative functions, another one-third believe the professional education function is most emphasized, but generally, they feel that the support function of supervisors is low. Most new social workers believe that, given the current policies for disability case management and the characteristics of supervisors, supervisors tend to work at a fast pace. They lead with a goal-oriented approach, focusing on problem-solving and performance, which requires time to process emotionally. As a result, providing immediate emotional support to new social workers is more challenging.

Their (supervisor's) characteristics are more like someone who works at a fast pace, just like everyone else, quickly finishing things. But I think one small drawback is that, when they talk about emotional support, it’s hard for them to empathize. It's like the concept of just handing you a tissue when you cry. Sometimes, when you're crying, they might be at a loss for what to do. Our supervisor just needs some time to process and provide emotional support. (Social Worker-2)

The current situation of supervisors leading new social workers

(1) The focus is on teaching administrative and professional aspects.

Supervisors primarily focus on teaching administrative and professional aspects when educating new social workers. In the administrative aspect, they mainly explain the organization and personnel systems, as well as the disability case management service process. In terms of professional education, there are different methods of guidance, but most follow a mentorship approach, similar to an apprenticeship, with experienced workers mentoring newcomers. This includes case visits and record writing, with some supervisors leading personally and others receiving assistance from senior colleagues. Regarding relevant service skills, supervisors typically follow the organization's training schedule, or some supervisors adjust seating arrangements so that new social workers can easily approach them for questions. Disability case management supervisors generally expect new social workers to have a certain service load within one to three months after starting and to be able to work independently after about six months.

I use a mentorship approach similar to this... For professional case visits, I don't let them do it alone. At least one or two people will accompany them. So basically, we use the senior-junior system to guide our new social workers. In terms of professional services, they usually get the hang of it in about a month... (Supervisor-1)

We expect that after three months, you should have a certain service load, and we assign a mentor to guide them... (time for mentoring) Generally, it's about six months. But there was one case where it took over a year to get them ready because we had to consider their situation. I think everyone is different... (Supervisor-2)

The organization has a training schedule, and when a new worker comes in, they will take certain courses. The schedule is adjusted according to the social worker's experience level, from the very beginning, I've always adjusted the seating arrangements. Now, I sit two new social workers in front of me so that when they need to discuss a case, they can just turn around and ask me. (Supervisor-3)

I take them on case visits, whether they are new or experienced. I also arrange for other social workers to assist... After the visit, I ask them to write an assessment report, and from what they write, I can tell how their previous experience informs their assessments... I always review the ISP (Individual Service Plan) and give them feedback. I will guide them step by step... (Service record part) I also asked OO, who plays a minor supervisory role, to help me keep an eye on the service records below. (Supervisor-4)

(2) There are some differences between what new social workers need and what supervisors believe they need.

When working as personal caretakers for people with disabilities, new social workers and supervisors have different views on what abilities they should have. Supervisors believe that personal managers with disabilities should have positive personality traits, a willingness to interact with the Internet, and the ability to collect and compile information.

However, new social workers believe that there are four key aspects to playing the role of a case manager effectively. The first is the knowledge aspect, such as understanding the medical and health conditions of people with disabilities. The second is attitude preparation, which includes how to stay calm in emergencies, distinguish the depth of services and responsibilities, manage time, maintain a flexible and diverse perspective, and have the courage to take risks. The third is assessment ability, which involves gathering and categorizing information, establishing relationships, and mastering the depth of the assessment. Finally, the fourth aspect is the practical implementation of services, such as negotiation skills, resource linkage and matching, inter-professional cooperation, and empowering individuals.

When working with people with disabilities, since they often have medical needs, it’s important to have some knowledge of medicine, which can also help with inter-professional collaboration. (Social Worker-3)

It’s essential to distinguish which tasks should be done by the case manager, which ones the person can handle on their own, or which ones can be done by the family members. This ability is quite important. (Social Worker-4)

We need to organize and categorize the issues within the cases, observe what problems the service recipients may have missed or not expressed, and what we, as social workers, can identify. Establishing relationships, whether with the case or with different resources, is key. (Social Worker-2)

What we can do is provide them with empowerment and the ability to take control. What we do is identify the issues, find solutions, deal with the problems, and solve them... and repeat this effort consistently. (Social Worker-8)

Thoughts on training for new personal care managers for people with disabilities

In training new staff, supervisors, when carrying out supervisory duties, often rely on their past experiences as supervisees to consider what kind of educational training they can provide to new social workers, in addition to the established plans for newcomers set by the organization. However, supervisors believe that the current curriculum-based training provided by the authorities is more general for all social workers and tends to be repetitive. There is no specialized training for new staff, and it is difficult to assess how well the new social workers absorb the training. Furthermore, the teaching of professional social work qualities is mostly done through daily interactions, making it difficult to implement a standardized training program.

For example, OO has its own (standards), such as the required hours for on-the-job training for new staff. I guide them more in a one-on-one manner. However, I don’t guide them case by case, because when I joined, I wasn’t trained that way, and I don’t have the time to do that for each case. (Supervisor-4)

(Regarding communication skills, learning attitude, enthusiasm, emotional control, etc., were these addressed in the training?) It’s difficult, really difficult. It’s more about everyday interactions... (Supervisor-2)

Honestly, the courses organized by the government every year are always the same, they just repeat. These courses get repetitive, and every time you attend, it’s pretty much the same... After attending, whether or not you absorb anything is another story; it’s just about meeting the time requirement. (Supervisor-2)

From the perspective of new social workers, when looking at the training process for newcomers, it is found that the primary concern is fear of disturbing others or not knowing where the problem lies. They often resort to trial-and-error learning, trying to build practical knowledge through experience. Secondly, new social workers feel that the training is vague, but having someone to guide them makes them feel more at ease. Furthermore, they believe that the training is somewhat formalized and usually follows a training schedule, but it may not effectively address their current state, making it difficult to absorb the knowledge. Lastly, new social workers feel overlooked, as no one seems to care about their learning process.

The scheduled training courses are completed, and questions can be asked afterward. However, there is hesitation about disturbing others, as they might be busy or dealing with other matters. Therefore, I do some research on my own and learn by doing—for instance, building personal connections with some partner organizations. (Social Worker-5)

Through feedback, the supervisor discusses it with me. I think it’s okay, but things still feel quite vague. (Social Worker-4)

There are similar courses, just a piece of paper with a checklist. After the lecture, it’s not necessarily applicable to actual work. Newcomers have weaker absorption and might not be able to apply what they’ve learned. It feels like there’s training, but it’s disconnected. (Social Worker-1)

It feels like being left to fend for myself. The case files are just placed on the desk for me to look through on my own. (Social Worker-7)

The impact of supervisory functions and new social workers' professional competencies on service effectiveness

(1) The professional competencies influencing service effectiveness

Both supervisors and new social workers emphasized that achieving high service effectiveness requires comprehensive assessment capabilities. Additionally, supervisors highlighted the need for improved counseling skills, as these are critical for facilitating accurate assessments and fostering professional relationships.

However, this study also revealed that the development of professional competencies involves not only internal organizational factors, such as assessment abilities and counseling skills but also external factors. These include workload, assigned cases, and other administrative tasks, which collectively contribute to delays and pressures in case management, administrative duties, service delivery, and documentation. These factors significantly impact the overall effectiveness of case management services.

However, in case assessments, further improvement is needed. Often, I focus only on their expectations and immediate realities but fail to explore deeper aspects. For instance, why they developed certain conditions, their subsequent treatment needs, additional support, or medical assistance. Sometimes, I only see the surface and miss the comprehensive picture of their long-term needs. (Social Worker-2)

First is counseling skills. Second might be enhancing knowledge of legal or judicial treatments, but I believe counseling skills are the most crucial. (Supervisor-4)

Honestly, I think plans often can't keep up with changes. For example, there was one time I had to handle a case assigned directly by the mayor. Early in the morning, I was called to the OO district, and the entire day was spent there. None of my planned tasks for that day got done because I was focused solely on the mayor's assigned case.(Social Worker-1)

We calculate by working days—about 20 per month. They have to take on cases, handle administrative tasks, meet case volume requirements, and fulfill assignments. Currently, the screening mechanism for cases isn't optimal. They also lack effective communication skills for remote interviews (e.g., by phone), so they end up having to visit every case in person. Everyone is operating under a high-pressure environment. (Supervisor-2)

Self-assessment of service efficiency by supervisors and new social workers

In evaluating service efficiency, supervisors primarily measure it based on the new social worker's familiarity with diverse aspects of service recipients, assessment skills, and the depth of record writing. Supervisors generally believe that new social workers can become fully independent within six months, with an intensive review of records and workload conducted during the first three months. On the other hand, new social workers estimate that their current service efficiency reaches about 50–70% of their self-expectations. The gap between their performance and expectations is often attributed to delays in documentation, which frequently requires them to work beyond regular hours. Additionally, they believe it takes at least six months to fully adapt to handling service cases, even when there are no exceptional challenges with the service recipients.

Because the cases we handle now are becoming increasingly diverse… I feel that case management social workers today are like all-around experts. For instance, we have to know how to handle situations like declaring a death, dealing with cases where there are no family members, and much more. Social workers have to acquire a wide range of skills gradually. (Supervisor-1)

(Assessing service efficiency) involves looking at how well one writes records, formulates plans, observes and evaluates situations, and assesses abilities overall. (Supervisor-3)

As for my situation, I’m able to categorize issues and organize tasks, but when it comes to assessing cases, I still need significant improvement… Sometimes, I only see the surface and fail to view the entire picture comprehensively. My evaluation ability is still only at about 40–50%.

(Social Worker 2)

It takes about six months to handle simple cases, but for more complicated ones, I still often need to ask for help or look up information online.

(Social Worker-3)

I don’t think I’ve fully adapted yet. While the introductory training courses provided some conceptual understanding, I find it difficult to apply them in practice. (Social Worker-9)

(3) Fostering new social workers and enhancing service efficiency through diverse support

Finally, both supervisors and new social workers expressed hopes for increased support in fostering new talent and enhancing service efficiency. Both parties emphasized the need for support from regulatory authorities, including financial backing and a clearer delineation of roles and responsibilities. Supervisors further highlighted the need for organizational recognition of their efforts in planning training programs and budget applications. Meanwhile, new social workers expressed a desire for real-time guidance during practical operations. They also hoped for more diverse and knowledge-rich training courses to better prepare them for the field.

The authorities need to clearly define and execute their roles, including the case referral function. These aspects should be made clearer.(Supervisor- 2)

It would be better if there was a reference tool, like a dictionary, to explain things like monitoring, low-income applications, and operation modes. When encountering issues, it would be helpful to look it up first and only ask more experienced social workers when there is an operational problem. This would save time because the time spent on trial and error is a waste. (Social Worker-6)

Now I can't think of anything else the supervisor should assist with, but I think I’ll realize what areas I need help with when I encounter problems. It would be helpful to have someone available to answer questions anytime. (Social Worker-9)

Different courses and diverse topics, such as finance, law, and other knowledge-based subjects, would allow us to have different perspectives when we are thinking. (Social Worker-7)

Conclusion and suggestions

This paper aims to understand the current situation of supervisors of PWDs in leading new social workers, and the impact of supervisory functions on the professional knowledge and skills development of new social workers and service effectiveness. Through focus groups with supervisors and new social workers, based on the average age, years of service, education and certification of supervisors and new social workers, the focus group discussions included supervisors’ thoughts on their own supervisory style and the training and effectiveness of new social workers., and understand the abilities that new social workers should have to engage in this business, as well as the assistance experience and service effectiveness provided by supervisors since they joined the job. Based on the findings, the researchers have synthesized the following conclusions and made recommendations based on their conclusions.

Conclusion

(1) Different positions and expectations regarding supervisory responsibilities

• Major Premise: Both supervisors and new social workers value the supervisor’s personality traits, emotional stability, resource connection, and role as a mediator.

• Minor Premise: Due to current policy trends and the fact that the average supervisory experience of supervisors in this study is only one year, the supervisory stage is still in the process of role transition and adaptation, leading to a lack of maturity and confidence.

• Conclusion: As a result, achieving goals is prioritized, and supervisors’ leadership traits are more goal-oriented, with less emphasis on emotional support and empathetic functions. The supervisory functions primarily focus on administrative and professional aspects.

(2) Although there are new employee training programs, they are difficult to tailor to the learning state of newcomers

• Major Premise: Both supervisors and new social workers agree that comprehensive assessment abilities are essential for personal caretaker abilities and service effectiveness for people with disabilities.

• Minor Premise: Supervisors believe that personal caretakers should possess positive personality traits, be willing to interact with networks, and have conversation skills, which are crucial for assessment and building professional relationships.

• Conclusion: New social workers feel that the focus should be more on acquiring knowledge, preparing attitudes, and learning how to implement services.

(3) Training new employee should not only rely on supervisors

• Major Premise: Both supervisors and new social workers believe that it takes about six months of learning, but they are still hindered by internal factors, such as insufficient professional knowledge, and external factors, such as caseload and assigned cases.

• Minor Premise: These factors affect the delay in administrative tasks, service delivery, and record-keeping, and in turn, influence their expectations of service outcomes.

• Conclusion: Therefore, both supervisors and new social workers hope that the competent authorities can provide more assistance and support, including funding and clearer delineation of responsibilities with other network units.

Suggestions

(1) New supervisors should receive adequate training and support

The supervisory function is influenced by the supervisor's years of experience, background, and emotional intelligence in the supervisory relationship, which may prevent the full display of supportive functions. Therefore, it is recommended to provide training resources for new supervisors. Within the organization, during the supervisory development process, teaching and supporting new supervisors in overcoming potential challenges they may face can help them develop their supervisory functions, ultimately assisting those being supervised and improving service effectiveness.

(2) Facing a risk society, supervisory agencies should reassess caseload

Following the rise of managerialism, outsourcing through contracts has controlled service outcomes and outputs, making the importance of service quality even more critical. With the advent of a risk society, it is not only the professionals who face risks with service users but also the need for sensitivity in risk identification, management, and the responsibility to reduce risks. Therefore, it is recommended that supervisory agencies reassess and recalculate a reasonable caseload, ensuring both the protection of service quality and the safety of the staff.

(3) Establish supervisory support for supervisors to relieve their stress and enhance their supervisory function

Supervisors also need opportunities to review their supervisory work and reflect on their work status. Establishing a supervisory mechanism for supervisors can not only provide current supervisors with clarification and consultation but also offer space and time to alleviate their stress and emotions. This allows supervisors to recharge briefly and perform better afterward.

(4) Establish a standardized training module for new social workers in disability case management services, and allow flexibility

Focusing on individuals with disabilities and integrating the professional services of family (social welfare) centers, the current use of community resources as the direction for case management services requires gradual adjustments in the arrangement and content of educational training courses to enhance professional knowledge. Therefore, it is recommended that the planning of educational training should include essential courses while allowing flexibility in response to changes in the environment and policies.

(5) It is suggested that in the future, the disability management system can be compared with that of other counties and cities in Taiwan

The weakness of this study is that it only takes the case management center for people with disabilities in City A as the main research object. The suggestions provided are applicable to City A and cannot be extrapolated to all counties and cities in Taiwan. It is recommended that research can be conducted in other counties and cities in the future. After comparison, we can formulate a training strategy for new social workers that is close to the Taiwan Case Management Center for People with Disabilities and supervise it.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Holloway, E. L. (1995). Clinical Supervision: A System Approach. California: Sage Publications, Inc View

Zhong, W. (2022). Ideal supervision activities and effectiveness evaluation—the perspective of social welfare organization workers. Taiwan Journal of Community Work and Community Research, 12(1), 47-108.

Hsu Zu-Wei (2007). Deconstructing the "Profession": The Process of Social Work University Graduates Leaving Social Work. Nantou: Master's thesis, Department of Social Policy and Social Work, Jinan University.

Liang Mei-Jung, Liu Li-Wen (2008). Geographical Information System - A new working method suitable for early treatment case management services. Taiwan Association of Social Work Professionals 2008 Annual Conference. Taipei: Taiwan Association of Social Work Professionals.

Liang Mei-Jung, Yao Fen-Zhi (2019). Research on the integration of legal needs assessment and case management services for people with disabilities. Taiwan Journal of Community Work and Community Research, 9 (2), 113-160.

Yao, Fen-Zhi (2016). Analysis, review and development of the current situation of case management and career transition services for people with disabilities. Taiwan Journal of Community Work and Community Research, 6 (1), 77-138.

Chen Zheng-Zhi, Hsu Ting-Han (2015). The next mile of the new disability assessment system: discussing the use of case management to connect follow-up service planning. Community Development Quarterly, 150, 154-163.

Hsu Su-Bin, Chen Mei-Zhi, Lin Yi-Hsuan, and Chuang Sui-Tzu (2016). Analysis of the caregiving pressure and demand patterns of the main family caregivers - taking people with disabilities in Taichung City as an example. Community Development and Welfare Services academic seminar. Taichung City: Department of Social Work and Child and Adolescent Welfare, Jingyi University.

Lee Ting-Hsuan, Lee Ming-Feng (2019). A preliminary analysis of the research themes and methods of supervisory relationships in Taiwan's helping professions. Taiwanese Journal of Social Work Supervision, 2, 27-52.

Bernard & Goodyear (2004). Fundamentals of clinical supervision. (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. View

Tseng Hua-Yuan (2001). Supervision work. In Jiang Liang-Yan, Tseng Hua-Yuan, and Tian Li- Zhu (eds.). Introduction to Social Work, 203-226. Taipei: National Air University.

Mo Li-Li (1995). Social work supervision and consultation. In Lee Tseng-Lu (Editor-in-Chief). Introduction to Social Work, 236-247. Taipei: Chuliu Books.

Munson, C.E. (1993). Clinical social work supervision (2nd ed.). New York: Taylor View

Kadushin, A.& Harkness, D. (2002). Supervision in social work (4th. Ed). New York: Columbia University Press. View

French, J. R., & Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Studies in social power. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan. View

Lin, Pei-Jin (2023). A preliminary study on the practice of social work supervision in Taiwan: Comparing the perspectives of supervisees, supervisors and supervisors. Journal of Social Work Practice and Research, 13, 39-72.

Liu, Hsiang-Lan (2018). Stage changes in social work career: Practical framework for novice social work supervisors. Taiwan Journal of Social Work Supervision, 1, 77-105.

Dai Shi-Mei, Lin Yi-Ru, Lu Nan-Ching (2018). A preliminary study on the functional training needs and training and development model of social work supervision: Taking the Social Affairs Bureau of the New Taipei City Government as an example. Taiwan Social Work Supervision Journal, 1, 57-75.

Lin, W. Y. (2000). The Development of Social Work and Social Welfare Education in my country. Journal of Social Work, 6, 123-161.

Tseng Hua-Yuan (2007). Constructing a service quality-oriented social work professional system in Taiwan. Community Development Quarterly, 120, 106-114.

Zheng Su-Fen, Zheng Chi-Wei (2017). Self-experience Tansuo for establishing service knowledge and ability of new career transition case management workers with disabilities. Kaohsiung City Government Social Affairs Bureau Barrier-free Home.

Ya-Rong Chou (1997). Application of Focus Group Method in Survey Research. Survey Research, 3, 51-73.

Yin, R. (2014). Case Study Research Design and Methods (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 282 pages. View