Journal of Social Work and Welfare Policy Volume 3 (2025), Article ID: JSWWP-144

https://doi.org/10.33790/jswwp1100144Research Article

A Grounded Theory Analysis of Multiple Sclerosis Caregiver Interviews: Utilizing Pearlin's Stress Process Model to Explore the Gender Effects of Care

Jennifer C. Hughes1, John Hughes2, Elizabeth P. Talbot3, and James R. Carter4*

1,3,4School of Social Work and Human Services, Wright State University, United States.

2College of Medicine, Cincinnati University, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: James R. Carter, Associate Professor, School of Social Work and Human Services, Wright State University, Millett Hall 359, 3640 Colonel Glenn Hwy, Dayton, United States.

Received date: 11th March, 2025

Accepted date: 25th April, 2025

Published date: 28th April, 2025

Citation: Hughes, J. L., Hughes, J., Talbot, E. P., & Carter, J. R., (2025). A Grounded Theory Analysis of Multiple Sclerosis Caregiver Interviews: Utilizing Pearlin's Stress Process Model to Explore the Gender Effects of Care. J Soci Work Welf Policy, 3(1): 144.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) affects more than two million people worldwide. Providing care for MS patients differs from providing care for other illnesses due to the early onset of the disease, a varying illness progression, and because MS patients are predominantly female. This qualitative research study applied Pearlin’s Stress Process Model (SPM) to explore MS caregiving in a homogeneous group of caregiver/patient dyads. Qualitative interviews were conducted with both MS patients and their caregivers utilizing grounded theory to explore the MS caregiving phenomenon. Pearlin’s SPM was used to evaluate the qualitative data, which provided insight into the gendered nature of the MS caregiving experience. This model is advantageous to help understand the intricacies of the MS care experience. This data and analysis draw from the dissertation research of the first author, Dr. Jennifer Hughes (2012), who examined the gender aspect of caregiving relationships between couples when one member of the couple dyad had been diagnosed with MS and was the receiver of care from the other member in the relationship and designated as the caregiver.

Keywords: Caregiving, Multiple Sclerosis, Pearlin’s Stress Process Model, Qualitative Research, Gender

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, progressive, and degenerative inflammatory disease affecting the central nervous system. It is characterized by a variety of disorders including issues with mobility and balance, that damage the central nervous system. The damage is further complicated by “cognitive disorders, spasticity, pain, weakness, sensory loss, paresis, speech disorders, sphincter problems, sexual dysfunction, and fatigue” [1].

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) estimates that 2.3 million individuals are diagnosed with multiple sclerosis worldwide, and approximately one million people are diagnosed with MS in the United States. This is likely a combination of factors including that women engage with healthcare more often, and are more likely to express symtoms during the visits. MS is three times more common in women than men, placing many women in the role of requiring care over time as the disease progresses [1-3] representing a role reversal of the expected caregiver actually being the recipient of care. Although there are advances in medications to slow the progression of MS and address the symptoms of the disease, there are currently no medical interventions to eliminate or cure the disease.

Unpaid, nonprofessional care is usually provided by loved ones, usually family members who receive no financial reimbursement. This type of informal care is common and has psychological and social advantages for families and family people with MS [1, 4]. Most individuals prefer the informal caregiving when provided by family members. These caregiver relationships can be a major factor in the quality of life for MS patients and their overall psychological adaptation to the physical illness [1,5,6].

Caregivers are defined as individuals who provide direct care and are unpaid supportive individuals with whom there is a personal relationship [7]. Caregivers are also defined as “hidden patients” because of the physical, emotional, and economic burdens necessary to assist their loved ones [8].

Unlike care providers for other illnesses, research into MS caregiver demographics is limited and data is inconsistent. The age and gender breakdown of MS caregivers varies considerably and is dependent on the relationship of the caregiver to the care recipient.

The care needs of individuals with MS are variable [9]. Most individuals with MS remain in their own homes requiring some type of in-home care assistance [1,10], which is usually the responsibility of family members and loved ones [7]. As the disease progresses, the opportunity to remain at home is made possible through a strong network involving health services, social care workers, volunteers, and family members. The informal and increasing caregiver responsibilities are assumed by family members, especially as the disease progresses.

Providing care for a chronically ill individual is stressful for caregivers. Extensive research on care and caregivers has largely focused on the general care phenomena [11-14] rather than the increased care needs as the disease progresses. The quality of care provided by caregivers has a profound impact on patients’ social roles and family members’ well-being [1,15]. This makes it important for patients, their families, and society to understand the MS caregiving and caregiver needs and the impact of caring on significant relationships.

Over time, those caring for individuals with a disability experience an increased risk of stress, depression, ability to cope with problems, mental and physical health challenges, work-life interruption, and overall poor quality of life [1,11,15]. Because of the early age of onset for MS patients, caregiving responsibilities can last for decades. As the disease progresses, the MS patient experiences a decrease in movement, and an increase in pain, fatigue, and incontinence. The patient’s body image changes, and there is a decline in the patient’s attractiveness and appearance. These and other changes, such as cognitive functioning, can cause the deterioration of the emotional bond between the spouse and the patient [1,11]. The effects of providing care are often overwhelming for the caregiver, resulting in changing the patient and caregiver roles, restrictions, economic concerns, employment problems, and a decline in social relationships [1,15,16]. Research identifies an increased risk of fatigue, loneliness, and isolation for caregivers [8,11,17].

Approximately 70% of caregiving responsibilities are provided by spouses [8]. Rarely discussed are changes in the marital relationship and satisfaction [1] Ozen et al. [1] reported sexual dysfunction resulting in a change in passion or desire. Caregivers often ignore these issues and rarely discuss them as they are considered private family issues (p.1863). It has been suggested that ignoring sexual issues leads to a decrease in the quality of the marital relationship and increases the potential for divorce [1].

The limited research on care and caregivers has largely focused on the general care phenomena [11-14,18]. More specific research on the effects of caregiving on caregivers is less available. This lack of knowledge and the complex demand of time and personal loss for caregivers of persons with MS is concerning. The roles and perceptions of MS patients’ family care providers require further study for the health care system to provide the depth and breadth of services needed, and to support the emotional and physical health of caregivers [6,7,17-20].

Unlike care providers for other illnesses, research into MS caregiver demographics is limited [7]. There are gaps in the research on MS as it pertains to caregivers, their quality of life, marital relationships, and relationships among family members. Patients are typically diagnosed with MS as young or middle-aged adults at about the time individuals are establishing intimate relationships and partnerships [21].

The dynamics of providing care for MS patients are unique because of the early age of onset in young adult life. The lack of knowledge about caregiving for MS patients, and the demand of personal time and loss to caregivers is concerning [6,7,17-20]. The unpredictable course of the disease and recent advances in medication management delay the progression of the illness, and have increased the life expectancy of persons with MS. It lengthens the time a patient needs care and lengthens the caregivers changed role and responsibilities [17]. Therefore, it is important to understand the impact of caregiving on individuals, marriages, and families.

Purpose

This paper aims to examine further Hughes's [22] findings on the effects of gender on the caregiver role using a grounded theory lens, an assumption that there are differences based on gender, and expanding on Pearlin’s Stress Process Model (SPM) as a lens for analysis. This research is part of a dissertation study that was approved by the IRB Committee at the University of Utah. The Neuroscience Research Center in Dayton, Ohio accepted the University of Utah IRB approval and did not require additional IRB application or approval for the collection of data [23].

A person-in-environment perspective has been adopted as a framework for understanding the relationship between caregivers and disabled family members; and a feminist view of caregiving [24] provided a lens through which to understand caregiving as an activity of relationships and moral development based on a universal experience of having been cared for. Pearlin’s SPM was utilized as a lens to assess and analyze the data to understand better the caregiver/ patient dyad, the moral responsibilities assumed by the caregiver, the relationships between the caregiver and the care receiver, and the stress associated with caregiving [23].

Pearlin’s SPM explains the caregiving process shared by most caregivers, regardless of individual illness. The model accounts for individual differences in the background and context, which allows for flexibility with a wide range of care-providing experiences related to how individual caregivers process and experience stress through various roles. It offers an archetype for understanding the entirety of the caregiving situation, including individual differences that each couple brings to the situation. This model is durable and malleable for guiding caregiving experience research and remains relevant to ongoing caregiving exploration [23,25].

Method

A sample of convenience was sought with identifiable homogeneous factors of causation, for saturation. Homogeneous factors of participants included heterosexual couples and MS patients who did not require alternative living facilities. The age range of the sample was from 32 – 59 years. Ten couples were recruited and participated in the study. Research limitations included limited transferability [23].

Participants were selected from the patient population at Neurology Specialists in Dayton, Ohio, which treats a large number of patients with MS. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and demographic information was collected. Criteria for inclusion required that at least one member of the couple had a diagnosis of MS. Twenty-nine semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with the ten caregiver/patient dyads. Additionally, there were five interviews with each female patient and five interviews with each male patient [23].

The questions were designed to illuminate gender differences when providing care for MS patients. The sample consisted of both male and female caregivers, specifically five female and five male caregivers, providing a balanced gender perspective [23].

The interviews took place at the research center or another mutually agreed-upon location and lasted 60-90 minutes. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Some participants had difficulty with mobility, so reasonable accommodations were made to reduce the travel burden. Each participant answered detailed questions about caregiving and care receiving, stress associated with illness, and stress associated with receiving care and providing care. Participants were presented with a copy of the transcripts and allowed to change or clarify answers. Identifying information was removed, and participants were given pseudonyms [23].

Interviews with the caregiver and care receiver occurred separately. A husband-wife couple interview occurred after the participants reviewed their interview transcripts. Interview questions were open-ended and selected as a way to encourage participant exploration of the care phenomena. They were also meant to provide a framework for conversation, not just responsive answers. Individual interviews allowed the participants the opportunity to construct the experience of care and provided the opportunity for communication and exchange of dialogue between the participant and the researcher. Additionally, the participant was allowed to guide the inquiry process to improve overall rigor. A third interview was conducted with both members of the couple dyad, which provided an opportunity for the participants to co-construct the care experience. A final interview allowed participants to review the transcripts, provide member checking of transcripts, and review rigor [23].

The qualitative research software NVivo was utilized for coding, data management, gathering themes, and evaluation. Researchers utilized grounded theory to collect and analyze research data, and Pearlin’s SPM was used to evaluate the transcripts to develop an understanding of the caregiving situation [23].

The homogeneous study population allowed for saturation with this somewhat small sample size (N=20). Participants began replicating themes after completing the individual interviews, which supports the conclusion that adequate data was obtained to develop a robust understanding of the study phenomena [23].

Demographics

Participant demographic characteristics included age, race, household composition, illness onset age, education level, household economic status, and employment status. Pseudonyms were used to maintain participant confidentiality [23].

Caregivers’ age range was 32-58 years, with a mean age of 47 years and a standard deviation of 9.4 years. MS patients’ age range was 41-59 years, with a mean age of 48 years and a standard deviation of 7.1 years. All participants were Caucasian. Three couples lived by themselves; two couples lived with one child; four couples lived with two children; and one couple lived with four children. MS was diagnosed as early as age 19 and as late as 46, with the mean age of diagnosis being age 37 and a standard deviation of 8.0 years [23].

The level of education varied. On average, patients were more highly educated than caregivers. The median patient education level was some college or a two-year degree, and the median caregiver education level was high school or some college. Male patients were the most educated, while male caregivers were the least educated. The median education range for male patients was reported as a two or four-year college degree, and the male caregivers reported their education as a high school education. Female caregivers and female patients had similar education levels, with most reporting a two-year degree.

The household economic status ranged from less than $20,000 to over $199,000, with the median household income range reported as $36,000-$50,000. Two patient participants declined to report household income. Four of the female patients were unemployed, and one was employed. Three of the male patients were unemployed, and two were employed. All five female caregivers were employed; two male caregivers were employed, and three were unemployed.

Applying Pearlin’s Stress Process Model

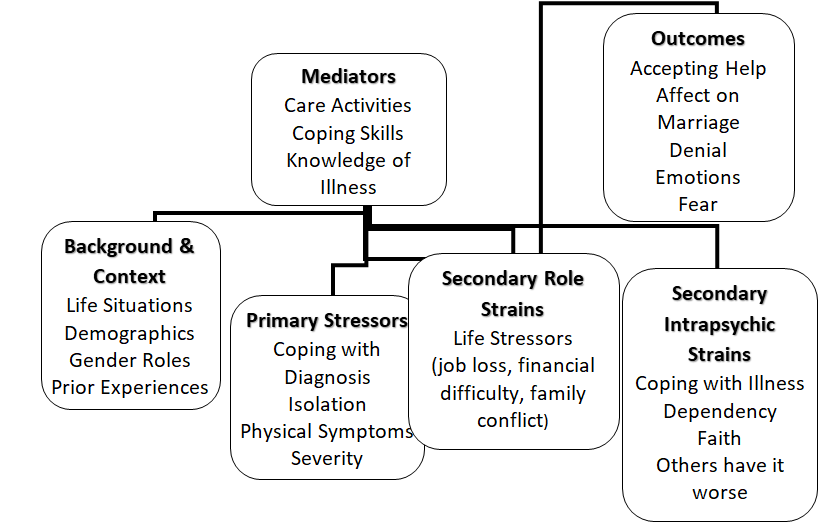

In addition to the MS diagnosis, patients and caregivers similarly experienced a wide range of life situations described and exemplified in Pearlin’s SPM. Characteristics specific to this research were applied to Pearlin’s SPM (see Figure 1). Life situations provide the background and context that affect caregivers’ experience with strain. The model suggests that various factors influence coping with an illness. For example, age or gender, being elderly or a woman affects the caregiving role. The items relative to the background and content were evaluated from the participants’ demographic information using grounded theory analysis and applied to Pearlin’s SPM [23].

The analysis showed that gendered roles were specific to Pearlin’s background and context area. An individual brings background context to the caregiving experience, impacting how the individual copes and provides care. Pearlin further explained that caregiver stress is not a unitary phenomenon but a mix of experiences that vary among caregivers. The caregiver participants in the present study discussed a wide range of experiences that shaped the background and context of the MS condition, such as job injury, ovarian tumor, loss of a child, diabetes, caregiver’s job loss, caregiver unemployment, back surgery, insurance company paperwork, financial strain, and problems with employers. One participant experienced the loss of several loved ones, including his son. He stated:

My mom died in March of 2006, and one of our best friends… lost his home, so we put him up for a little while. He died in September, then my son went in November…so that was a tough year. But I try to stay as upbeat as I can [23].

For this participant, the challenge of coping with grief and loss was in addition to surviving his MS. MS does not occur in isolation; rather, it is one of many life situations that cause stress and require various coping techniques. This individual’s caregiver was also coping with these losses (mother-in-law, son, and family friend). All of these situations occur in addition to the direct problems associated with MS. Providing care for an individual with MS is challenging on its own, given the age of onset, unpredictable disease course, episodic nature, debilitating nature, and disabling symptoms [23].

Results

Primary Stressors

Pearlin’s SPM identifies primary stressors as symptoms directly experienced by MS patients, such as memory loss, vision problems, hand weakness, difficulty walking, pace, numbness, tingling, slurred speech, drop-foot, general weakness, difficulty regulating body temperature, falling, loss of stamina, bowel problems, bladder problems, stumbling, dizziness, neuropathy, mobility, fatigue, temporary paralyzes, and depression. Applying Pearlin’s SPM, four content areas were identified as primary stressors: coping with the diagnosis, isolation, physical symptoms, and severity. One male patient discusses his driving limitations, which were a primary stressor:

I’m limited in my driving. That ‘automatic transmission only’ is on my driver’s license. I don’t have the strength in my left leg to clutch so I don’t do that. I don’t drive a stick anymore…but you know, I do drive short distances. I’ll drive around town and the neighborhood [23].

For this patient’s caregiver, driving restrictions represent an increase in care responsibilities. In this case, the caregiver needs to transport her husband to various activities which is a primary stressor for the caregiver.

In addition to the physical symptoms, primary stressors also include isolation experienced by the care dyad. Primary stressors are directly identified as related to the illness. In this study, three female patients, one female caregiver, and one male caregiver discussed isolation.

I feel like I isolate myself on purpose. I do…because I’m a burden. People think I’m drunk. I feel like people look at me like, oh my God, here she comes, oh God. You know, I just feel like nobody wants me. Everybody has someone in their life… where you see somebody and go, oh please no, or you see the caller ID and go, ‘I’m not answering the phone because I don’t want to be on the phone for two and a half hours.’ I feel like that person on the other end. So, I don’t reach out to anybody because I don’t want to be that person. I don’t want anyone to be afraid of me [23].

Female caregiver “Laura,” who was in her late forties, talked about how MS isolated the couple from social events. “I know he takes his medicine on Sundays, so he does not feel good, and we don’t do as much…but you know, I’ve slowed way down too. You know we’re getting older, so it is ok.” Male caregiver “Bob” discussed isolation from friendships: “Her individual friends…they just stopped coming around…they just don’t come around” [23]. Isolation or abandonment is a primary stressor related to MS because MS caregivers and patients tend to isolate themselves which affects the caregiver as either the person experiencing isolation or filling that void for the person with MS [23].

Secondary Role Strain

Secondary role strain is an after-effect for the caregiver dealing with the MS patient. The participants discussed life stressors (8 times in a total of 13 interviews) that were directly related to Pearlin’s concept of secondary role strain, such as job loss, financial difficulties, and family conflict. These incidents were indirectly affected in that the MS interfered with secondary but equally important life expectations. For example, one male caregiver, “Bob,” illustrated the concept of secondary role strain when discussing prioritizing:

Only time it becomes a lot if I have a lot of other things to do and I’m trying to get it done and then have to stop to, you know, meet her needs. But it’s not that bad. I guess, it is hard to explain, I guess…if you love your spouse, if love is still there, and because something like this happened, it shouldn’t change your love…you just take on more responsibilities [23].

He further reports:

I think I push myself too much…she says I push myself too much; but like I said, it’s to the point if I don’t do it who is? You know it’s a lot of responsibility. I’m dependent on a lot…I just don’t think anything about it. It’s just something that’s got to be done [23].

This caregiver understood the layers of responsibility required to provide adequate care to his loved one, but he also felt the time constraint and burden associated with caregiving.

Secondary Intrapsychic Strain

Caregiver’s secondary intrapsychic strains comprise self-esteem, mastery, competence, and gain, all of which affect the caregiver’s experience. Previous research identified three content areas correlated with secondary role strain: caregiver coping with illness, dependency (dependent and independent), and others have it worse.’ Participants described techniques they used to cope with MS that correlated with Pearlin’s intrapsychic strain. One caregiver, “Bob,” discussed coping:

It’s been a common question. They’ll ask me how you deal with it. Well, I have no choice. I have to keep going. If I don’t keep going, where will we be then? I might feel sad that this has happened to her, but I block it out. That’s the best way I can put it, because like I said…I do it all. So now, if I let myself come down, who knows where we’ll be? Who knows what chain of reaction that could happen? You know I love her to death; she’s my wife, of course. But I can’t let…that pity set in everyday life…emotions play a big part in MS [23].

These participant quotes provide insight into the secondary intrapsychic strain caregivers use to cope with caregiving responsibilities. It is difficult to master the caregiver role, given the shifting nature of responsibilities and the patient’s functional decline.

Furthermore, caregivers in this study typically focused more on the patient’s illness and less on the strain they may be experiencing as a result of providing care. Although participants were told the research was on the caregiving relationship, they consistently referred to their partner’s direct experience of the illness instead of the strain of being a care provider [23], suggesting empathy and concern for their loved one’s suffering.

Outcomes

Caregivers experienced a range of emotions associated with caregiving, which were evaluated as outcomes in Pearlin’s SPM. Participants (number of participants reported in parenthesis following the name of the theme) most often described accepting assistance (n=12) and the effect on their marital relationship (n=19) as outcomes. Other participants described experiencing fear (n=8), loss (n=8), uncertainty (n=7), frustration (n=6), acceptance of their situation (n=5), anxiety (n=4), anger at their situation (n=3), depression (n=3), and blame (n=2) [23].

Emotional and physical health. In Pearlin’s SPM, caregivers’ emotional and physical health problems are considered outcomes. Four of the five female caregivers explored anxiety as an outcome associated with the caregiving relationship. In the present study, this anxiety outcome was experienced exclusively by female caregivers [23].

One caregiver, “Jessica,” stated, “There is always a worry. You never know what is going to happen.” Another, “Laura,” described herself as “…a great worrier, always have been.” A third caregiver, “Mary,” touched on depression as an outcome with her comment, “Well, you know, I mean, it was sad. I mean you think, oh, you know life is going to be different, and you do not know what to do; so, you feel a little helpless at first of just not knowing” [23].

Other outcomes examples included Nate, who had diabetes while caring for his wife, who had MS, and Jessica, who experienced a hysterectomy and lost a son while caring for her husband, who had MS [23].

These physical health problems are considered outcomes in Pearlin’s SPM. It is unknown if participants' health problems occurring after assuming caregiver responsibilities are directly correlated to caregiving roles. However, MS caregivers report substantial physical and psychological health concerns while providing care to individuals with MS [26].

Marital Relationships. The effect of MS on the marital relationship was also discussed throughout the interviews. One female caregiver discussed how her role as wife had shifted to that of caregiver when she described the process of coping with MS. She reported:

It took us a while to get through it because I wanted to make his life as easy as possible for him, take as much burden as I could from him so he could handle things physically and emotionally with the anxiety, and also encourage him. It came to a point where I was like, "I kind of feel like your nursemaid" [23].

Another outcome, accepting assistance from others, was difficult for some patients. Female caregiver, “Brenda” described this struggle:

He does not like getting help. Once in a while, he will, but that’s when his energy. The level is the lowest. I can tell when he needs a hand, or he needs help getting up or just, you know, stabilizing and things, and we laugh about that too; I’ll hold his hand, and he’s like, ‘I’m okay.’ And I say, ‘I know, I just want to hold your hand’ [23].

Finally, Pearlin’s SPM asserts that individuals’ ability to cope and access to social support mediates the experience and can positively and negatively affect individual outcomes. In the present study, such mediators included care activities, coping skills, knowledge of the illness, and support systems. Participants identified the following coping skills: humor, anger, minimization, and acceptance [23].

For some, learning about MS mitigated the effect of the illness. Participants discussed the process they used to learn more about the MS diagnosis. For example, one female caregiver reported, “We didn’t know anything about it…because we didn’t know anybody with it. So, I just started getting stuff at the library, books and stuff. So, I just started checking stuff…at the library since I have that resource.” This participant mediated the uncertainty of the illness by seeking knowledge [23].

Anxiety. Four of the five female caregivers reported anxiety as a result of providing care to a loved one with MS. No male caregivers mentioned or discussed anxiety in this content [23].

Discussion

This research used Pearlin’s SPM to develop an understanding of the care experience for MS Caregivers. Pearlin’s seminal theoretical perspective sets the groundwork for identifying how the social construction of gendered tasks plays a significant role in the care relationship. The phenomenon of the gender relationship in caring for MS patients was explored first by examining how caregivers and those with MS experience the caregiving relationship [23]. A significant finding that needs further exploration is in the area of anxiety. As indicated, there were no male caregivers who mentioned or discussed feelings of anxiety in the process of caregiving, while four of the five female caregivers reported anxiety.

Gender influences both the provision and perceptions of care in MS caregiving, beginning with the understanding of who should undertake the caregiving tasks in the first place. Awareness develops when the responsibility falls outside the patients’ or caregiver’s usual parameters. Society plays a significant role in dictating male and female roles, and the social construction of gender ultimately influences expectations, roles, and feelings associated with both the giving and receiving ends of the caregiving experience [23].

Prior research suggested that women caregivers have competing demands and additional responsibilities, which might account for the anxiety experienced by the women caregivers in this study [14]. In Pearlin’s SPM, gender does seem to play a role in the caregiving experience. First, gender is a part of the background and context that the caregiver brings to the act of caregiving. Second, female caregivers reported more emotional strain (primary stressor) as a result of the care relationship and may, therefore, have more difficulty coping with their caregiving role [23].

Male caregivers in this study did not specifically mention feelings of anxiety related to the strain of providing care, although one male caregiver mentioned “sadness.” The anxiety difference among male and female caregivers could be, in part, because the female caregivers worked outside the home and the male caregiver did not, resulting in an increase of primary stressors for the female caregivers, although research by Perrin et al. [27] support the idea that female MS caregivers reported higher levels of anxiety than their male counterparts [27]. Gender differences appear to be part of the caregiving experience despite the fact that women provide the majority of informal care and caregiving [23].

One noted similarity between men and women in Pearlin’s SPM is that both female and male caregivers focused on the patient as a primary concern and neglected their own needs in the care relationship. They communicated the difficulties their partner experienced and rarely spoke of their hardship. Gender is an essential factor in the context of caring and chronic illness and cannot be separated from the experience [23].

Primary Stressors

Meeting patients’ and caregivers' needs for social support depends on resource availability. Therefore, social support in the care relationship becomes a resource (available and utilized or inaccessible but needed) specifically for the care provider. Social support may have different implications for the care receiver, who might view the need for support as burdensome and an indicator of decline in their disease progression. This could be further explored in future research [23].

Acknowledging the resources available to patients and caregivers is crucial to understanding the care experience. Individuals use resources (e.g., financial, support measures, or time) when available. Caregivers are left to fill the gaps where available resources are lacking. For example:

MONEY + TIME + PEOPLE + DISEASE TRAJECTORY = CARE SITUATION

This model is supported by the discussion by Maguire et al. (2020) on factors associated with caregiver burden in MS (2020). Maguire identifies similar aspects: time spent caring, social support, level of disability (i.e., type of MS, symptoms), income, and relationship to the individual with MS as related to caregiver burden [23].

Secondary Role Strain

Research on caregiving in the United States reports that 61% of all caregivers were employed while providing care, resulting in a gender breakdown of 67% male and 58% female caregivers who were employed while providing care. Our data is quite different in that 100% of female and 40% of male caregivers were employed. This could also be a result of the education level of our caregiver population because caregivers working outside the home are more likely to have obtained some college education. In our study, the male caregivers had a high school diploma, and the female caregivers all reported having some college education. The relationship between caregiver and employment status is complex and involves more factors than gender [23,28].

Male caregivers’ unemployment contributed to limited financial resources and increased time availability for male caregivers to contribute to the care experience. If a spouse is not working and lacks money, it becomes necessary for that spouse to provide direct care. With one female patient dyad, the husband was unemployed. However, the family had a close connection to the female patient’s parents, who lived down the street and provided much assistance to the family. That particular dyad lacked financial resources but utilized the resources of available family support. Female caregivers all worked outside the home, thus attempting to meet the financial needs of the dyad. Working outside the home decreased the availability of these care partners and shifted the caregiving dynamics. This result suggests that the caregiving experience is greatly influenced by the availability of several crucial elements: time, money, and people. Future research should investigate the influence of these elements: financial resources, support measures of people, and available time. A given level of primary care is necessary; therefore, caregivers must make up the difference when other types of resources, such as money, time, or people, are insufficient [23].

Secondary Intrapsychic Strain

In formally identifying the elements examined in this study, social scientists can assist families in maximizing their resources and optimizing their human experience, increasing self-esteem, mastery, and competence among caregivers and care receivers. For example, a family may have ample social support or human capital resources. Hence, the social worker assists the family in maximizing those resources while simultaneously helping them to identify ways to improve financial availability by reducing expenses for medical care [23].

An area of intrapsychic strain that might be useful to explore through Perlin’s SPM is the role of faith in the patient/caregiver relationship. Faith-based relationships in difficult times often rely on the strength of the relationship and the belief that there is a God who sees their struggle, and gives them comfort, endurance, healing, and the ability to persevere in times of trouble.

Perlin’s SPM also examines Outcomes such as accepting help and its relationship to Intrapsychic Strain/Secondary Strain. Faith should also be considered when examining the church's impact when it offers help to members who are struggling with health. Friends from the church who offer their time to care for an MS patient, giving the caregiver a break of time, provide both caregiver and care receiver with peace and comfort, particularly during some of the most complex challenges.

Outcomes

This has a critical community application because individuals coping with MS in the United States have numerous and varied types of resources available or unavailable. These benefits vary widely depending on each person’s access to health insurance and health care. One individual may have access to drug cost benefits while another may not. Another may need to become financially bankrupt to qualify for Governmental Health Insurance under the Medicaid Insurance program; if an individual is significantly disabled for two years, they may qualify for Governmental Medicare Insurance that does not require a demonstration of financial need. The intricacies of multiple varying health care plans and examining financial resources are crucial to providing good care. However, accomplishing it is exceedingly challenging and requires specialized practice knowledge. Delving into a person’s private health insurance benefits has been considered a personal responsibility and remains taboo. The postulate gives social workers a starting point to begin the discussion of available resources and should include an assessment of resources, including personal health benefits. The NMSS announced a survey examining the MS Economic Burden [29], demonstrating an awareness of this ongoing situation and the need for further exploration.

Furthermore, the care situation formula is useful in assessing family resources and shifting them to provide maximum benefit for families. The amount of required care for one individual is constant yet increases annually. Reallocating the amount of support available for care to MS patients and their families will help social workers relieve the burden of care experienced by families [23].

Summary

The purpose of this study was to apply Perlin’s SPM to a group of MS patients to explore the unique caregiving experience and enhance understanding. Unexpected barriers encountered were the unanticipated challenge of securing male patient participants. We also found that discussing caregiver relationships may introduce stress into the caregiving dyad, representing an ethical concern for this research and future projects like this. Future research could improve the generalizability by studying more diverse populations, with more variation in age, ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and culture, to see how those factors influence the caregiving situation [23].

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Özen, S., Karatas, T., & Polat, U. (2021). Perceived social support, mental health, and marital satisfaction in multiple sclerosis patients. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 57, 1862- 1875. View

McKenna, O., Fakolade, A., Cardwell, K., & Pilutti, L.A. (2022). A continuum of languishing to flourishing: Exploring experiences of psychological resilience in multiple sclerosis family caregivers. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 17, 2135480. View

Wallin M.T. Culpepper, W.J., Campbell, J.D., Nelson, L.M., Langer-Gould, A., Marrie, R.A., Cutter, G.R., Kaye, W.E., Wager, L., Tremlett, H., Buka, S.L., Dilokthornsakul, P., Tropop, B., Chen, L.H., LaRocca, N.G. & US Multiple Sclerosis Prevalence (2019). The prevalence of MS in the United States, a population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology, 92 (10), E1029-E1040. View

Carton, H., Loos, R., Pacolet, J., Versieck, K., & Vlietinck, R. (2000). A quantitative study of unpaid caregiving in multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis, 6, 274-279. View

Schwartz, C & Frohner, R. (2005). Contribution of demographic, medical, and social support variables in predicting the mental health of dimension of quality of life among people with multiple sclerosis. Health and Social Work, 30 (3), 203-212. View

Long, D. & Miller, B. (1991). Suicidal tendency and multiple sclerosis. Health and Social Work, 16(2), 104-109. View

Rajachandrakumar, R. & Finlayson, M. (2022). Multiple sclerosis caregiving: A systematic scoping review to map the current state of knowledge. Health and Social Care in the Community 30, e874-e897. View

Benini, S., Pellegrini, E., Descovich, C., & Lugaresi, A. (2023). Burden and resources in caregivers of people with multiple sclerosis: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 18(4), e0265297. View

Maguire, R. & Magure, P. (2020). Caregiver burden in multiple sclerosis: Recent trends and future directions. Current Neurology and Neuroscience reports, 20(7), 18. View

Martindale-Adams, J., Zuber, J., Levin, M., Burns, R., Graney, M., & Nichols, L. (2020). Integrating caregiver support into multiple sclerosis care. Multiple Sclerosis International 2020 (Article ID 3436726). View

Cummins, R. (2001). The subjective well-being of people caring for a family member with a severe disability at home: A review. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 26(1), 83-100. View

Dobrof, J., Ebenstein, H., Dodd, S.J., & Epstein, I. (2006). Caregivers and Professionals Partnership Caregiver Resource Center: Assessing a hospital support program for family caregivers. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 9(1), 196-205. View

Pearlin, L., Mullan, J., Semple, S. & Skaff, M. (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30(5), 583-594. View

Stone, R., Cafferata, G.L. & Sangle, J. (1987). Caregivers of the frail elderly. Gerontologist, 27, 617-626. View

Hakim, E., Bakheit, A., Bryant, T., Roberts, M., McIntosh Michaels, S., Spackmans, A., Martin, J., & McLellan, D., (2000). The social impact of multiple sclerosis: A study of 305 patients and their relatives. Disability and Rehabilitation, 22(6), 288-293. View

O’Brien, M. (1993). Multiple sclerosis: Stressors and coping strategies in spousal caregivers. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 10(3), 123-135. View

Odessa, I., Shufrin, I.,(2022). Nonlinear mechanics of fragmented beams. European Journal of Mechanics - A/Solids; 93. View

Pakenham, K.I. (2002). Development of a measure of coping with multiple sclerosis caregiving. Psychology & Health, 17(1), 97-118.View

O’Hara, L., DeSouza, L. & Ide, L. (2004). The nature of caregiving in a community sample of people with multiple sclerosis. Disability and Rehabilitation, 26(24), 1401-1410. View

Chipchase, S., & Lincoln, N. (2001). Factors associated with carer strain in carer’s people with multiple sclerosis. Disability and Rehabilitation, 23 (17), 768-776. View

Perlin, L.I., & Skaff, M.M. (1996). Stress and the life course: A paradigmatic alliance. The Gerontologist, 36(2), 239-247. View

Hughes, J.C. (2016). Social construction of gender: Stories of multiple sclerosis care. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research, 10(3), 180-196. View

Hughes, J. N. (2012). Teachers as managers of students' peer context. In A. M. Ryan & G. W. Ladd (Eds.), Peer relationships and adjustment at school (pp. 189–218). IAP Information Age Publishing. View

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women's development. Harvard University Press. View

Aneshensel, C.S. (2015). Sociological inquiry into mental health: The legacy of Leonard I. Pearlin. Journal of Health & Social Behavior, 56(2), 166-178. View

McKenzie, T., Quig, M., Tyry, T., Marrie, R., Cutter, G., Shearin, E.. Johnson, K., & Simsarian, J. (2015). Care partners and multiple sclerosis: Differential effects on men and women. International Journal of MS Care 17(6) , 253-260. View

Perrin, P.B., Panyavin, I., Morlett Paredes, A., Aguayo, A., Macias, M.A., Rabago, B., Picot, S.J.F., & Arango-Lasprilla, J.C. (2015). A disproportionate burden of care: Gender differences in mental health, health-related quality of life, and social support in Mexican multiple sclerosis caregivers. Behavioral Neurology, 283-958. View

Caregiving in the U.S. 2020. (2020). PN, 74(8), 44. View

National MS Society (2020). National MS Society launches Economic Burden Survey. View