Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices Volume 8 (2024), Article ID: JPHIP-226

https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100226Research Article

Intergenerational Engagements and Ageism: A Systematic Review

Katherine Rodriguez1, Marina Celly Martins Ribeiro de Souza2*, Mara M Ribeiro3, and Natalia C Horta4

1Undergraduate Student, Department of Public Health, The College of New Jersey, USA.

2*Professor, Department of Public Health, The College of New Jersey, USA.

3Assistant Professor, Department of Nursing, Faculdade de Ciências Médicas de Minas Gerais, Brazil.

4Professor, Department of Medicine, Pontifical Catholic University of Minas Gerais, Brazil.

*Corresponding Author Details: Marina Celly Martins Ribeiro de Souza, RN, PhD, CNE, CHPN, Professor, Department of Public Health, The College of New Jersey, USA.

Received date: 16th May, 2024

Accepted date: 06th June, 2024

Published date: 08th June, 2024

Citation: Rodriguez, K., Souza, M. C. M. R., Ribeiro, M. M., & Horta, N. C., (2024). Intergenerational Engagements and Ageism: A Systematic Review. J Pub Health Issue Pract 8(1): 226.

Copyright: ©2024, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Abstract

Intergenerational studies aim to understand the different social and biological elements that impact engagement between the geriatric population and children. Intergenerational studies may come in the form of initiatives, campaigns, activities and centers that promote interaction between people of different generations. The object of this study is to examine the relationship between intergenerational engagements and ageism through a systematic literature review. This systematic literature examines different intergenerational studies, both qualitative and quantitative, across a series of databases utilizing a wide range of identifiers, to ultimately comprehend negative or positive relationships between intergenerational contact and ageist stereotypes. The final selection of 41 full papers detailed a variety of impacts of intergenerational contact and ageism on older adults. The different articles highlighted three emerging themes, all covering a variety of subtopics. The largest group of studies explored educational programs and health promotion activities in college aged students. Another theme noted throughout the selection process was ageism in healthcare workers. Finally, a small selection of papers covered the impact of COVID-19 isolation and change in perceptions since 2020.

Keywords: Intergenerational Relationships, Ageism,Intergenerational Studies, Elderly.

Introduction

The global population is aging rapidly and life expectancy is steadily increasing, casting attention on vital aging that may have an unintended consequence for the geriatric population and creating ageist attitudes in younger generations [1].

Aging results from a variety of biological changes and internal damages which over time leads to a decline in physical and mental health. This decline is characterized by a high risk of disease such as Dementia, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and ultimately death. Aging is also typically linked to important life transitions such as retirement, becoming grand-parents, widows and relocation to nursing homes and assisted living houses [2]. Older people’s aging process is largely affected by their genetics but also their physical and social environments such as sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic status. With that being said, all older people age differently and some may have better physical and emotional health than their younger counterparts.

In addition, most people today can expect to live into their sixties and beyond. Every country worldwide is noticing growth in the size of older populations [2]. From a global perspective, it is expected that by 2050 there will be 1.25 million people 65 and over in less developed areas, approximately 757 million more people than in 2020 [2]. The global life expectancy is soaring and global aging is being recognized as an important demographic. A decline in fertility rates and a heavy increase in life expectancy is making global aging a new interdisciplinary interest for health organizations and governments around the world. Thus, it is important to foster better relationships among older and younger generations through intergenerational engagement.

As society evolves, cultural gaps can widen, making it difficult for generations to understand each other. Changes in family structures, living arrangements, and migration trends can also influence intergenerational relationships. In this sense, intergenerational studies aim to understand the different social and biological elements that impact engagement between the geriatric population and children. Intergenerational studies may come in the form of initiatives, campaigns, activities and centers that promote interaction between people of different generations. These interactions are meant to establish a deep understanding of human progression across the lifespan. One of the main challenges circling intergenerational living is specifically related to how to care for, communicate with, and entertain the youngest of the family, the children of the children of the children [3-5].

Therefore, intergenerational activities are imperative in the effort to reduce ageism. Ageism is known as any bias, prejudice or discrimination towards others because of their age. With so much negativity surrounding the concept of aging, it is important for intergenerational centers to raise awareness about this ongoing social issue and lessen societal pressure to remain youthful. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) half of the world’s population is ageist against older people. In Europe, younger people are reporting more age discrimination than any other age group [6]. The everlasting stigma around aging can be seen in many forms. Through public figures receiving cosmetic surgery to reduce the look of wrinkles, social media filters that make users appear younger and the anti-aging beauty market that profits off of this stigma. This stigma can result in intergenerational conflicts that can cause a divide in communities and families alike.

Intergenerational relationships are meant to create connections between the geriatric and youth populations, which give both generations a better understanding of each other. This engagement can help build valuable relationships and opportunities to learn from each other. Older generations can share wisdom and important life lessons that they have accrued over their lifetime while younger generations can help them better understand modern technology. Intergenerational relationships are essential in embracing aging and disproving negative stereotypes.

In this sense, this study aims to examine the relationship between intergenerational engagements and ageism through a systematic literature review.

Methodology

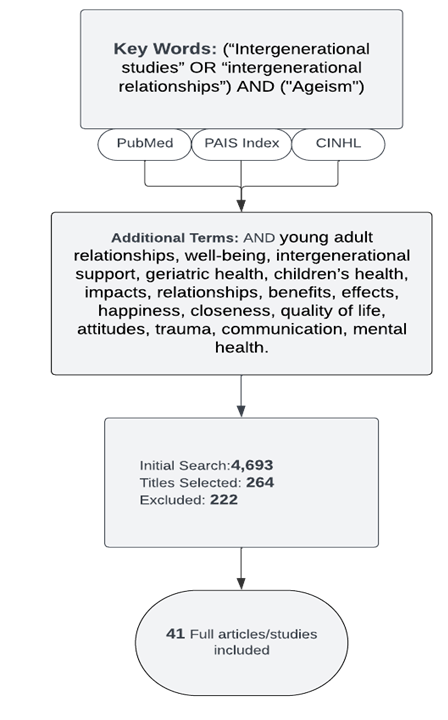

This systematic literature review examined different qualitative and quantitative intergenerational studies across a series of databases utilizing a wide range of identifiers, to ultimately comprehend negative or positive relationships between intergenerational contact and ageist stereotypes. Through a close review of experimental, and non-experimental studies, related literature reviews, and peer reviewed articles, several emerging themes were identified and utilized to quantify results. Materials were sourced from a search across scientific databases including, PubMed, Pais Index and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINHL). In each database, the keywords (“Intergenerational studies” OR “intergenerational relationships”) AND (“Ageism”) and (X) were used to search for related articles. Several descriptors were identified and used interchangeably in place of X, to narrow down search results and find literature related to that particular subtopic. Descriptors consisted of (young adult relationships, well-being, intergenerational support, geriatric health, children’s health, impacts, relationships, benefits, effects, happiness, closeness, quality of life, attitudes, trauma, communication, and mental health).

The initial search yielded 335 results in PubMed, 2,303 results in the PAIS index, and 2,055 results in CINHL. The first phase of paper selection included articles whose titles coincided with the aim of this literature review, to understand the relationship between intergenerational contact and ageism. Due to the broad variety of results, the CINHL database was not considered further. Therefore, the PAIS Index articles were narrowed down to 162 articles and 102 articles remained from the PubMed search. The second phase was a review of articles selected by title, 88 remained from the PubMed database and 115 from the PAIS Index. The third process of selection involved selecting papers by abstract; 83 from PubMed and 95 from PAIS Index. The last round of selection was a selection by full paper, this led to a total of 32 articles from PubMed and 10 from PAIS Index for a cumulative total of 41 articles. The final articles are originally published in a variety of languages, including English, Spanish, Portuguese, and are based in several countries such as Canada, China, and Ireland. A summary of these findings is outlined in Figure 1.

Results and Discussion

The final selection of 41 full papers detailed a variety of impacts of intergenerational contact and ageism on older adults. The different articles highlighted three emerging themes, all covering a variety of subtopics. The largest group of studies explored educational programs and health promotion activities in college aged students. Another theme noted throughout the selection process, ageism in healthcare workers. Finally, a small selection of papers covered the impact of COVID-19 isolation and change in perceptions since 2020.

Programs in Universities

A large sum of articles focused their studies on college-aged students, as researchers believe the younger generation is crucial for understanding shifts in societal perspectives about aging. Researchers implemented programs in universities across the world, to gauge common attitudes, behaviors and beliefs young adults hold towards the older population [3-11]. These programs aimed to assess emerging stereotypes and introduce intergenerational interactions in classrooms. Ultimately, each study followed a different model or theory but all had the goal of allowing young adults to learn from the lessons of an older generation, and in turn, the older group could better grasp modern challenges facing the youth today [12]. Following the Positive Education about Aging and Contact Experiences (PEACE) model, one study provided in-person and online intergenerational contact opportunities to 1,845 undergraduate students in a non gerontology course [13]. Over the course of an entire semester (11 weeks) participants were randomly assigned a variety of tasks, including watching educational videos, analyzing infographics or reading written information. Results from this study indicate improved outlooks towards aging, better relationships with older groups, and increased knowledge of natural aging [13].

These results were further corroborated by an intergenerational reminiscence intervention conducted on college students in a separate study. Feedback gathered from the participants showed negative attitudes towards older adults, calling this population “stingy” or noting comments such as “seniors live in the past” [14]. A total of 64 college students from a public university in North Texas were recruited for this intervention program, in which students were matched with older adults with cognitive impairments and made weekly phone calls for the span of ten weeks. Students recorded all data from their weekly phone calls, and overall results indicated gradual improvement in college students' attitudes towards older adults, showing promising change in previous sentiments and room for personal growth.

From an international perspective, the CRENCO project in Spain assessed pre and post intervention learning outcomes from an intergenerational study conducted in primary and secondary schools as well as a day hospital in Catalonia [15]. Focusing on the health of the older participants, there was significant improvement to the health-related quality of life as well as self-reported health status, as a result of social support and encouragement from younger participants [15]. Also from the perspective of the older generation, participants in another study shared that an integral part of this style program is their performance; keeping up to pace with younger participants and re-claiming their space in the conversation [16].

In addition to this, other studies aimed to explore the benefits of intergenerational programs for non-university students. Solely focusing on young adults, regardless of their academic enrollment status, many researchers are connecting older adults to their younger counterparts (aged 23-30) through a variety of programs including weekly meetings, experimental imaginative manipulations, life story interviews (LSI), and online surveys [17-24]. These studies combined different program designs to measure ageist attitudes both before and after the intervention and provided researchers with insight into how ageist attitudes develop over time in young adults outside of an academic environment. Many also highlighted the importance of Intergenerational Practice Programs (IPPs) and the need for versatile communication styles and activities that adapt to in-person or virtual settings [25]. These studies also allow older adults to share their own insights and familiarize themselves with emerging technologies. In light of this, one particular study collaborated with older adults to co-design intergenerational programs using digital technologies [26]. Not only does this create a more inclusive design space, but simultaneously tackles hostile ageist attitudes by seeing older adults and researchers as partners.

In contrast, other studies focused on creating strong bonds specifically between grandparents and their biological grandchildren [27,28]. This type of intervention aimed to improve intergenerational solidarity by streamlining communication between family members. Results reinforced the importance of frequent contact with older generations within families, to reduce ageist attitudes in general society and dismantle unjust stereotypes. One study found that ageist attitudes among younger generations stem from anxiety about their own aging process, possibility of death, and a lack of information about aging health [29]. To curb these beliefs, another study found that it is best to directly address stereotypes and engage in informative conversations rather than increasing warmth perceptions of older generations [30].

Ageism in Healthcare Workers

Newfound ageist attitudes exist across all professional industries, severely hindering collaboration and impeding progress towards intergenerational goals. According to research conducted across 29 nations, young and old generations see their counterparts as major threats to their collective power and beliefs [31]. This includes a study conducted in Cook Islands, where researchers believed residents of this small, close-knit region would share differing opinions regarding their contact with older generations in relation to the world at large [32]. Shockingly, residents’ views were not different from those living in industrialized nations, showing that ageism may affect all parts of the world. Naturally, this brought to light the presence of ageism in other margins, especially the quality of nursing home care for older adults; many researchers questioned if healthcare workers shared these negative beliefs towards their patients. This prompted studies around the world that investigated the prevalence of ageist attitudes among healthcare workers and their potential impact on the overall quality of the care they provide. Addressing these concerns is instrumental in creating age-inclusive practices among all industries, and to ensure respectful and ethical healthcare practices for all patients, regardless of age.

In South Korea, researchers conducted a study to understand nurses’ ageism attitudes and how this may affect their work. As age-related discrimination persists, researchers aim to understand potential implications for the patient and what led to these beliefs in healthcare workers. A total of 162 nurses completed a comprehensive survey to measure different factors influencing ageism, including clinical experience and cohabitation with older adults [33]. Results highlighted a number of new factors that lead to ageist attitudes, factors that were previously disregarded, and those that were once most important, such as gender, were not regarded in the study. Based on these findings, ageism education and older person care should be prioritized in healthcare settings and proper interventions should be implemented to prevent age-specific conflict. One particular study indicated that the most effective ways to reduce ageism are to enhance information about aging, improve quality and quantity of intergenerational communication, and promote reflective thinking among young adults [34]. A similar meta-analysis analyzed 63 intergenerational interventions to obtain knowledge about the best possible experiment or program style, overall concluding that a combination of intergenerational contact and education had the strongest results [35].

Post-Pandemic Ageist Attitudes

A smaller number of articles focused on ageism during and after the pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing ageist stereotypes and age-related discrimination in the workforce and in society. The pandemic brought to light a number of vulnerabilities faced by older adults, and an urgent need for intervention strategies to halt the expansion of newfound ageist attitudes. In Japan, germ aversion during the pandemic had a significant impact on ageist attitudes among the youth [36]. In an effort to remain as distanced as possible from infection, the Japanese youth developed negative attitudes towards older adults.

By the same token, the priority given to older adults upon availability of COVID-19 vaccines, along with their heightened susceptibility to complications which later reinforced the need for isolation, became catalysts for ageist social media trends such as the term “boomer” and the propagation of negative stereotypes towards older adults [37]. This caused a number of physical and emotional consequences, including heightened feelings of loneliness, a complete lack of social interaction, and victims of hate speech [38]. One particular case study aimed to tackle these physical effects while simultaneously dismantling the potency of age related stereotypes, through a nutritional intergenerational perspective [39]. This study implemented food related social activities to bring different generations together, relieve prior feelings of loneliness or sadness in older participants, and reiterate the importance of a nutritional diet.

During the pandemic, a study based in France analyzed how measures taken to reduce the impact of COVID-19 on older adults in the country, such as quarantine and visit bans in nursing homes, led to an increase in age-related discrimination. Researchers conducted interviews with older adults aged 63-92 years old living in urban areas of France, to understand their personal encounters with ageism during the pandemic. Interviewees recall negative experiences during the quarantine period, “ they said that the older adults were not allowed to go out. we're not pests! We're old enough to know what to do” [40]. Many reported ageist behaviors from those around them, but also recalled enhanced intergenerational solidarity towards the end.

In addition, a study conducted in Spain indicated that ageist attitudes have had an immense impact on the older people’s access to a plethora of resources, including healthcare [41]. Authors of this particular study created a series of propositions, based on observations and research, to improve intergenerational relationships and educate the public on aging. One of the proposals included disregarding age for consideration of services or goods, as researchers believed age is not a determining factor for either selection process. The pandemic undoubtedly fostered strong, negative opinions towards older adults, catalyzing a number of direct impacts to this population, many interviews recalling older persons referring to themselves as burdens or unhappy with their age, and reinforcing pre-existing stereotypes [42].

Limitations

This systematic literature review has several limitations. First, the specificity of the selected key words made for duplicates of the retrieved articles. The particularity of the added search terms almost always returned the same articles, posing a challenge to identify articles that directly addressed that subtopic. Additionally, the exclusion of other medicine and public health databases suggests a number of potential papers were missed. Due to the fact that the articles were sourced exclusively from PubMed and PAIS Index, other potentially suitable articles were not included in the final review.

Conclusion

To conclude, implementing intergenerational contact programs in both local and national formats is a great approach towards intergenerational solidarity and deconstruction of rising ageist attitudes. Considering both young and older people’s perceptions, intergenerational engagement has shown to significantly improve both ageist beliefs in the youth and overall health in their older counterparts. Additionally, intervention programs based both in person and virtually seem to alleviate previous germ aversion concerns set during the pandemic, reducing intergenerational tension. More studies should be conducted on the applicability of intergenerational programs across various cultural settings. Many international experiments are focused in Spain, South Korea, France, and some parts of the Middle East region. Going forward, understanding the sustainability of such programs in different regions will clarify additional challenges within diverse cultural contexts. Societal norms, familial structures and religious beliefs vary by culture, thus, the influence of such factors on intergenerational programs may vary. Finally, the different tools utilized as communication among participants need additional attention. All of the studies gathered participant feedback through a variety of formats including interview responses, surveys and written statements. More knowledge needs to become available on the best way to obtain participant responses, especially from older adults who may not be familiar with modern technology, to ensure that answers are as accurate and representative of their true feelings as possible.

Conflicts of Interest:

According to the writers, there is no conflict of interest.

References

Verhage, M., Thielman, L., de Kock, L., & Lindenberg, J. (2021). Coping of Older Adults in Times of COVID-19: Considerations of Temporality Among Dutch Older Adults. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences, 76(7), e290–e299.View

World Bank Group. (2022, March 28). How does an aging population affect a country?. World Bank. https://www. worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2016/09/05/uruguay-como afecta-pais-envejecimiento-poblacionView

Ramamonjiarivelo, Z., Osborne, R., Renick, O., & Sen, K., (2022). Assessing the Effectiveness of Intergenerational Virtual Service-Learning Intervention on Loneliness and Ageism: A Pre-Post Study. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 10(5), 893. View

Whyte, C., (2022). Adventures in Intergenerational Service Learning: Laughter, Friendship, and Life Advice. Canadian journal on aging = La revue canadienne du vieillissement, 41(2), 243–251.View

Muntsant, A., Ramírez-Boix, P., Leal-Campanario, R., Alcaín, F. J., & Giménez-Llort, L., (2021). The Spanish Intergenerational Study: Beliefs, Stereotypes, and Metacognition about Older People and Grandparents to Tackle Ageism. Geriatrics (Basel, Switzerland), geriatrics6030087 6(3), 87.View

World Health Organization. (2021, March 18). Ageing: Ageism. World Health Organization. View

June, A., & Andreoletti, C., (2020). Participation in intergenerational Service-Learning benefits older adults: A brief report. Gerontology & geriatrics education, 41(2), 169–174. View

Rowe, J. M., Kim, Y., Jang, E., & Ball, S., (2021). Further examination of knowledge and interactions in ageism among college students: Value for promoting university activities. Gerontology & geriatrics education, 42(3), 331–346.View

San-Martín-Gamboa, B., Zarrazquin, I., Fernandez-Atutxa, A., Cepeda-Miguel, S., Doncel-García, B., Imaz-Aramburu, I., Irazusta, A., & Fraile-Bermúdez, A. B., (2023). Reducing ageism combining ageing education with clinical practice: A prospective cohort study in health sciences students. Nursing Open, 10(6), 3854-3861.View

Beach, P., Hazzan, A. A., Dauenhauer, J., & Maine, K., (2024). "I learned that ageism is a thing now": education and engagement to improve student attitudes toward aging. Gerontology & geriatrics education, 1–17. Advance online publication.View

Lytle, A., & Levy, S. R., (2019). Reducing Ageism: Education About Aging and Extended Contact With Older Adults. The Gerontologist, 59(3), 580–588.View

Statham, E., (2009). Promoting intergenerational programmes: Where is the evidence to inform policy and practice? Evidence & Policy. 5(4):471-488. https://login. tcnj.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/ scholarly-journals/promoting-intergenerational-programmes where-is/docview/1947584655/se-2.View

Ashley, L., Jamie, M., MaryBeth, A., Sheri, R. L., (2021). Reducing Ageism With Brief Videos About Aging Education, Ageism, and Intergenerational Contact, The Gerontologist, Volume 61, Issue 7, October, Pages 1164–1168,View

Xu, L., Fields, N. L., Cassidy, J., Daniel, K. M., Cipher, D. J., & Troutman, B. A., (2023). Attitudes toward Aging among College Students: Results from an Intergenerational Reminiscence Project. Behavioral sciences (Basel, Switzerland), 13(7), 538. View

Domènech-Abella, J., Díaz-Cofine, S., Rubio-Valera, M., & Aznar-Lou, I., (2022). Evaluación pre-post de un programa intergeneracional para mejorar el bienestar en personas mayores y los estereotipos edadistas en alumnos de primaria y secundaria: proyecto CRENCO [Pre-post evaluation of an intergenerational program to improve wellbeing in older adults and age stereotypes in primary and secondary students: CRENCO project]. Revista espanola de geriatria y gerontologia, 57(3), 161–167.View

Elliott O'Dare, C., Timonen, V., & Conlon, C. (2019). Escaping 'the old fogey': Doing old age through intergenerational friendship. Journal of aging studies, 48, 67–75.View

Kahlbaugh, P., & Budnick, C. J., (2023). Benefits of Intergenerational Contact: Ageism, Subjective Well-Being, and Psychosocial Developmental Strengths of Wisdom and Identity. International journal of aging & human development, 96(2), 135–159.View

Hoffmann, C., & Kornadt, A. E., (2022). A Chip Off the Old Block? The Relationship of Family Factors and Young Adults' Views on Aging. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 808386.View

Chen, Z., & Zhang, X., (2022). We Were All Once Young: Reducing Hostile Ageism From Younger Adults' Perspective. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 793373.View

Kranz, D., Thomas, N. M., & Hofer, J., (2021). Changes in Age Stereotypes in Adolescent and Older Participants of an Intergenerational Encounter Program. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 658797.View

Mahoney, N., Wilson, Nathan, J. W., Buchanan A, Milbourn, B., Hoey C, Cordier, R., (2020). Older male mentors: Outcomes and perspectives of an intergenerational mentoring program for young adult males with intellectual disability. Health Promotion Journal of Australia. 31(1):16-25. https:// login.tcnj.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/ scholarly-journals/older-male-mentors-outcomes-perspectives/ docview/2357403950/se-2. doi: hpja.250.https://doi.org/10.1002/View

Korkiamäki, R., O'Dare, C. E., (2021). Intergenerational friendship as a conduit for social inclusion? insights from the “Book‐Ends”. Social Inclusion. 9(4):304-314. https:// login.tcnj.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/ scholarly-journals/intergenerational-friendship-as-conduit social/docview/2619554787/se-2. doi: https://doi.org/10.17645/ si.v9i4.4555.View

Laging, B., Slocombe, G., Liu, P., Radford, K., & Gorelik, A., (2022). The delivery of intergenerational programmes in the nursing home setting and impact on adolescents and older adults: A mixed studies systematic review. International journal of nursing studies, 133, 104281.View

Ermer, A. E., York, K., & Mauro, K., (2021). Addressing ageism using intergenerational performing arts interventions. Gerontology & geriatrics education, 42(3), 308–315. https:// doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2020.1737046View

Kosiol, J., & Perna, G. D., (2023). Watching Relationships Build over Time: A Video Analysis of a Hybrid Intergenerational Practice Program. Social Sciences, 12(2), 96.View

Mannheim, I., Weiss, D., van Zaalen, Y., & Wouters, E. J. M., (2023). An "ultimate partnership": Older persons' perspectives on age-stereotypes and intergenerational interaction in co designing digital technologies. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 113, 105050.View

Iliano, E., Beeckman, M., Latomme, J., & Cardon, G., (2022). The GRANDPACT Project: The Development and Evaluation of an Intergenerational Program for Grandchildren and Their Grandparents to Stimulate Physical Activity and Cognitive Function Using Co-Creation. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(12), 7150.View

Liao, T., Zhuoga, C., & Chen, X., (2023). Contact with grandparents and young people’s explicit and implicit attitudes toward older adults. BMC Psychology. 11:1-11. https://login. tcnj.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/ scholarly-journals/contact-with-grandparents-young-people-s explicit/docview/2877495281/se-2. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/ s40359-023-01344-7.View

Cooney, C., Minahan, J., & Siedlecki, K. L., (2021). Do Feelings and Knowledge About Aging Predict Ageism?. Journal of applied gerontology : the official journal of the Southern Gerontological Society, 40(1), 28–37.View

Cadieux, J., Chasteen, A. L., & Packer, D. J., (2019). Intergenerational Contact Predicts Attitudes Toward Older Adults Through Inclusion of the Outgroup in the Self. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences, 74(4), 575–584. View

Ayalon, L., (2019). Are Older Adults Perceived as A Threat to Society? Exploring Perceived Age-Based Threats in 29 Nations. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences, 74(7), 1256–1265.View

Frackowiak, T., Oleszkiewicz, A., Löckenhoff, C. E., Sorokowska, A., & Sorokowski, P. (2019). Community size and perception of older adults in the Cook Islands. PloS one, 14(7), e0219760.View

Hwang, E. H., & Kim, K. H. (2021). Quality of Gerontological Nursing and Ageism: What Factors Influence on Nurses' Ageism in South Korea?. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(8), 4091.View

Bétrisey, C., Carrier, A., Cardinal, J. F., Lagacé, M., Cohen, A. A., Beaulieu, M., … Levasseur, M. (2024). Which interventions with youths counter ageism toward older adults? Results from a realist review. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 45(2), 323–344.View

Nelson, T. D., (2019). Reducing Ageism: Which Interventions Work? American Journal of Public Health, 109(8), 1066-1067. View

Shimizu, Y., Hashimoto, T., & Karasawa, K. (2022). Influence of Contact Experience and Germ Aversion on Negative Attitudes Toward Older Adults: Role of Youth Identity. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 829742.View

Frey, K. T., & Bisconti, T. L. (2023). "Older, Entitled, and Extremely Out-of-Touch": Does "OK, Boomer" Signify the Emergence of a New Older Adult Stereotype?. Journal of applied gerontology : the official journal of the Southern Gerontological Society, 42(6), 1200–1211.View

Molina-Luque, F., Stončikaitė, I., Torres-González, T., Sanvicen Torné, P., (2022). Profiguration, active ageing, and creativity: Keys for quality of life and overcoming ageism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19(3):1564. https://login.tcnj.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https:// www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/profiguration-active ageing-creativity-keys/docview/2627533644/se-2.View

Jones, M., & Ismail, S. U., (2022). Bringing children and older people together through food: the promotion of intergenerational relationships across preschool, school and care home settings. Working with Older People, 26(2), 151-161.View

Barth, N., Guyot, J., Fraser, S. A., Lagacé, M., Adam, S., Gouttefarde, P., Goethals, L., Bechard, L., Bongue, B., Fundenberger, H., & Célarier, T. (2021). COVID-19 and Quarantine, a Catalyst for Ageism. Frontiers in public health, 9, 589244.View

Hernández Gómez, M. A., Sánchez Sánchez, N. J., & Fernández Domínguez, M. J. (2022). Análisis del edadismo durante la pandemia, un maltrato global hacia las personas mayores [Analysis of ageism during the pandemic, a global elder abuse]. Atencion primaria, 54(6), 102320.View

Choi, E. Y., Ko, S. H., & Jang, Y. (2021). "Better be dead than grow older:" A qualitative study on subjective aging among older Koreans. Journal of aging studies, 59, 100974.View