Journal of Rehabilitation Practices and Research Volume 6 (2025), Article ID: JRPR-157

https://doi.org/10.33790/jrpr1100157Research Article

Outcomes of A Sensory Garden for Caregivers of Individuals With Intellectual Developmental Disabilities

Jeffery Lucas*, Jadicus Burns, Madelyn Burton, Kasey Jackson, Charis Pickett, Cristina Sorensen, Brianna Terranova, and Emma Yates

Department of Occupational Therapy, Winston-Salem State University, 601 Martin Luther King Jr Dr, Winston-Salem, NC 27110, United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Jeffery Lucas, Assistant Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy, Department of Occupational Therapy, Winston-Salem State University, 601 Martin Luther King Jr Dr, Winston-Salem, NC 27110, United States.

Received date: 24th January, 2025

Accepted date: 06th January, 2025

Published date: 08th January, 2025

Citation: Lucas, J., Burns, J., Burton, M., Jackson, K., Pickett, C., Sorensen, C., Terranova, B., & Yates, E., (2025). Outcomes of A Sensory Garden for Caregivers of Individuals With Intellectual Developmental Disabilities. J Rehab Pract Res, 6(1):157.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine the utilization and benefits of a newly designed sensory garden for caregivers working with clients with Intellectual and Development Disabilities (IDD). Each semester Winston-Salem State University Occupational Therapy students complete Level IA, IB and Level IIA Fieldwork at this Adult Day Center serving clients with IDD. Students carefully designed and assembled a therapeutic sensory garden for clients and caregivers at the Adult Day Center. Students felt compelled to collect data on caregivers working with clients with IDD due to frequent turnover. During the fieldwork experience, students noticed high turnover and how negative it was influencing the client's overall performance. There are several studies that support the positive effects of a therapeutic sensory garden on various populations. However, there is limited evidence that connects a therapeutic sensory garden with caregivers working with individuals with IDD at an adult day center.

Twenty-five caregivers completed a survey while engaged in the sensory garden. This is a quantitative study completed through convenience sampling. Caregivers employed at the Adult Day Center with a newly established sensory garden were given consent forms to participate in the study. After completion of the consent form and agreement to participate in the study, caregivers were given a survey to complete while actively engaging in the garden.

Caregivers indicated that the sensory garden was frequently utilized, beneficial, and increased overall mood. As a result, direct effects and daily use improved mood which may decrease the risk of caregiver burnout and high turnover.

Keywords: Sensory Garden, Intellectual Developmental Disabilities, IDD, Caregivers, Adult Day Center

Introduction

Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) are differences that are present at birth and that uniquely affect the trajectory of the individual’s physical, intellectual, and/or emotional development. Many of these conditions affect multiple body parts or systems [1]. The effective delivery of healthcare for persons with intellectual disability requires participation and coordination between many different medical as well as other related disciplines and agencies that provide support services for persons with intellectual developmental disability [2]. Community agencies as an adult day program are essential for an individual with an intellectual developmental disability because they provide a variety of services such as: vocational training, paid work opportunities/ work tasks, recreation/leisure activities, and general skills training [3]. The fundamental purpose is to enhance independent functioning among adult consumers. Individuals with IDD commonly attend day centers to receive care and assistance daily. Adult day care services are defined as being “community based long term care services in a group setting during daytime hours” and are focused on those with cognitive and physical disabilities [4]. Facilities like these can serve a wide variety of disabilities concurrently including autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, and Down syndrome.

Several individuals with IDD can present challenging and agitated behavior. This can negatively impact a caregiver. Caregivers manage a myriad of responsibilities including activity planning, goal setting, conflict resolution and behavior modifications to name a few. As they support all the diverse needs and diagnoses, caregivers experience an increased physical and mental workload. Ryan et al. [5] lays out the challenges for staff of working with clients with IDD as they experience aggressive client behavior, employment instability, miscommunication amongst staff, low pay, long hours, an absence of training for the job, missing support systems, a lack of control in decisions, staff shortages, workplace inequality and more which contribute to workplace stress. This requires a high level of dedication and empathy from staff. These factors can lead to a caregiver becoming overwhelmed due to the emotional and organizational impact.

Staff mental and physical well-being at work is essential for providing high quality care. The caregivers at the adult day center play a vital role in the everyday lives of individuals with IDD by working closely in direct assistance of everyday tasks. The close relationship that is built between the client and caregiver is important to consider as the attitudes, emotional well-being, and type of care from the staff can affect the client's overall well-being. For example, people with IDD rely on caregivers to help meet physical, emotional, and social needs [6]. Without proper care and intervention from the caregivers, the client's quality of life can be affected negatively [6]. Therefore, it is important for caregivers to focus on their overall well-being to provide optimal care for their patients. In addition, it is important to have consistency in care with people who have IDD. According to a study conducted by Carli Friedman, “extended tenure of direct support professionals can help promote the health and safety of people with intellectual developmental disabilities” [7]. This study found that high turnover rates negatively affect the health and safety of individuals with IDD. However, the study failed to discuss ways to address turnover rates and burnout for people working with those who have IDD.

Consistency and longevity are important to maintain the quality of care for clients with IDD at an Adult Day Center. Furthermore, turnover can negatively impact interactions, care, services, and occupational performance of clients [8]. Implementing strategies and finding creative ways to support staff are crucial in preventing burnout in this environment. Caregivers are highly susceptible to experiencing burnout due to the extensive job demands. A solution is needed to ensure staff retainment to provide best possible care for clients at the Adult Day Center. Introducing nature into the workplace could be a solution to prevent burnout and decrease high turnover. The intention of this study is to provide support and onsite coping strategies amongst caregivers.

What is a Sensory Garden?

A sensory garden is designed to address the seven senses vision, hearing, touch, taste, smell, vestibular and proprioception, while fostering a more immersive and experiential connection with nature. Duncan et al. [9] described a sensory garden as a therapeutic garden “with an emphasis on color, fragrance, texture, natural form, seasonal interest and wildlife attraction” meant “to promote wellbeing, regardless of any presence or absence of diagnosis” [9]. In sensory gardens, the choice of each item and features are carefully organized to elicit sensory responses. A designed sensory garden goes beyond aesthetics, providing a holistic and enriching experience to explore, learn, and connect through all their senses [10]. This experience is enriching, not only for clients, but staff in ways to connect with nature. According to the American Heart Association [11], spending time in nature can help relieve stress and anxiety, improve overall mood and boost feelings of happiness and well-being. The intentions of this garden were for caregivers to spend time in nature to relieve /reduce stress and anxiety, improve mood and boost feelings of happiness and well-being. In an article written by Burton, it stated that a sensory garden has always sought to promote wellbeing, regardless of any presence or absence of diagnosis [12]. The emerging trend of sensory gardens has gained popularity in various settings, including schools, community agencies, healthcare facilities, and public spaces [10].

How does a sensory garden benefit staff?

Sensory gardens provide several benefits including a calm environment that stimulates the senses, but also a social atmosphere for fostering conversations [13]. This could increase social support and be a form of stress release within the workplace. If the gardens are used often, they can increase productivity and workplace wellbeing while reducing stress [9]. Involvement in outdoor activities can have a positive effect on people suffering from distress by alleviating symptoms [14]. Designing areas surrounding hospitals such therapeutic gardens can provide spaces for patients, staff, and family members to use and enjoy. According to Cordoza et al. [15] an outdoor garden introduced nurses at risk of burnout, emotional exhaustion and depersonalization decreased if they entered the garden with a notable negative emotion visual analog scale score, anger and tiredness decreased. It is proven that spending time in the garden walking, contemplating, or engaging in gardening activities could result in mood improvement and increased calmness [16].

Methodology

The study gathered quantitative data using convenience sampling. This is a correlational research design to discover the impact of the sensory garden on caregivers at an Adult Day Center. Twentyfive caregivers completed a survey while engaged in the sensory garden. Informed consent explaining the study’s purpose and that participation was voluntary obtained from all participants. Over ten weeks at the adult day center, participants were given access to the survey. Surveys were created through Microsoft Forms to collect all data, including consent forms and questionnaires. The questionnaires comprised seven questions, allowing participants to select responses that reflected their perspectives. These questions aimed to gather information on participants' mood before visiting the sensory garden, the duration and frequency of their visit, whether they visited alone or with others, how much the garden has helped reduce their stress, and whether their mood improved after the visit. Both data collection and analysis were conducted through Microsoft Forms, while Excel was used to identify and analyze data.

Participants

Twenty-five participants (25) were recruited from the adult day center to participate in this study. Sixteen females, five male and four other gender identity. The inclusion criteria were to be 21 years of age and older and currently employed at the center. Each participant completed a consent form prior to participation. A sensory garden experience survey was given during their visit to the garden.

Results

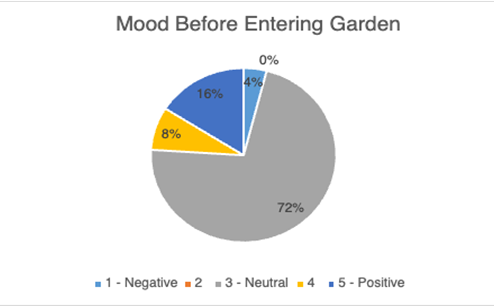

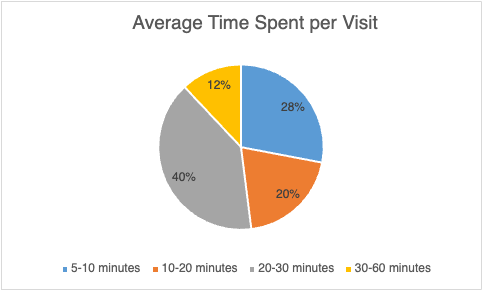

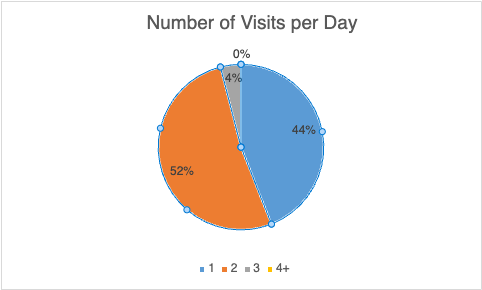

Four percent of participants indicated a negative mood prior to entering the garden, while 24% of participants reported a positive mood, and 72% indicated a neutral mood before entering the garden (see fig. 1). When asked about time spent in the garden, 40% of participants stated they spent 20-30 minutes, 28% spent 5-10 minutes, 20% spent 10-20 minutes, and 12%stated they spent 30- 60 minutes. Forty-four percent of participants spent 1-2 days in the garden, 36% spent five days, and 20% spent 3-4 days in the garden each week. Participants were asked how many times they visited the garden each day, 44% selected one visit, 52% selected two visits, 4% selected three visits, and no participants selected four or more visits result in an average daily visit of 1.6 times per day. Ninety-two percent of participants stated that they take a client into the garden, 4% stated they go with a colleague, and 4% stated they go alone. All participants agreed that the sensory garden was beneficial, with 96% stating it improved their mood and 4% reporting no change.

Discussion

The design of the sensory garden was strategically planned and designed to incorporate the seven senses. The focus was to create a place reflecting more tranquility than aesthetic appeal. The garden contained elements such as wind chimes, water features, lights, fragrant plants, textured paths, and seating areas to create a holistic sensory experience. This research examined the usage and benefits of a sensory garden for caregivers/staff working with clients with IDD. The participants experienced an improvement in mood, which is evident in 96% of the survey results. As a result, 56% of participants spent three to five days in the garden. Ninety-two percent of participants went into the garden with a client, but100%of those participants reported an improved mood. Although the sensory garden is frequently utilized to improve mood and well-being, staff are still responsible for caregiving duties. Only 8% of participants went to the sensory garden without a client. While not the aim of this study, this reinforces the assumption that caregivers spend a large amount of time with clients which contributes to high rates of burnout. Frequent exposure with clients who have challenging behaviors such as violence, aggression, and who are dependent upon caregivers is related to staff anxiety and work stress. Individuals that provide direct care are at higher risk for burnout due to the high emotional demand, variability of client behavior, and low occupational status, among other factors. Caregivers in this setting are among the nation’s most vulnerable workers due to extensive job demands and dependence of clients with IDD [17]. The poor reimbursement rates set for their services do not reflect the critically important services they provide [5].

Research suggests that burnout and stress can be reduced by organizations encouraging caregivers to participate in self-care [18]. Self-care is the practice of behaviors that promote well-being, counter work-related stress, and foster resilience. Self-care has been linked to self-compassion and mindfulness [18]. It is an ethical responsibility for mental health workers. According to the American Psychological Association [19], psychologist strive to understand their own possible effects of physical and mental health on the ability to whom they serve. Caregivers that engage in self-care experienced less burnout and secondary traumatic stress [18]. The sensory garden is beneficial to caregiver’s mood, and it is being frequently utilized. Increasing mood impacts risk of burnout, turnover and health and safety of clients with IDD. Having a place like a sensory garden at an adult day center is essential for caregivers’ mental health, self-care and ways to maximize work performance. However, to completely decompress and enjoy the full experience of the sensory garden one should spend that time without a client. Spending time alone in the sensory garden is one of many ways to encourage and promote selfcare in the workplace.

An organization can create a culture that encourages self-care amongst employees as well as empower employees [18]. It is important that organizations understand the importance of self-care to professional quality of life. Leadership plays an important role in employee self-care and well-being. Understanding self-care leaders can help caregivers with job demands, work design, reduce stress and managing resources. Excessive work demands, a decreased level of control and lack of support have been attributed to high levels of stress and burnout among caregivers working with clients with IDD [5]. Creating a workplace that is supportive, and sufficient leadership has improved job satisfaction and client care [20]. In a study done by Coats and Howe [21], indicated that an organizational supported work environment resulted in diminished exhaustion in this population and is highly important for reducing burnout. Therefore, providing increased flexibility, latitude and the opportunity to integrate selfcare into daily work routines are ways to promote job satisfaction and decrease risk of burnout.

Limitations

A limitation of this study was the small sample size due to scheduling conflicts amongst students and participants. The weather impacted data collection; rainy and cool days during the fall prevented staff from utilizing the garden. High turnover of staff also led to a loss of participants. There were several participants who agreed to participate in the study and when researchers followed up, the participants were no longer employed at the Adult Day Center. The impact of individual difference variables such as gender, age, and race are less clear, however, as the evidence base is limited.

Implications for Further Research

More research is warranted to determine if staff and caregivers are burned out. Burnout is a term used to describe emotional exhaustion resulting from work-related stress and other contributing factors of a personal nature [22]. It is commonly felt among those who provide care for the intellectually and developmentally disabled (IDD) population [23]. Burnout has been linked to poor productivity, outcomes, and decreased quality of care [22,24].

According to Finkelstein, et al., [22], more research is needed to determine the impact of burnout amongst caregivers of individuals with IDD. Studies have shown that this group is at risk of burnout due to job demands and challenging behavior of the clients. To assess burnout, using tools such as the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) at the Adult Day Center would be an appropriate choice to measure three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishments. Results from the MBI would provide administration with strategies to adequately support staff, solutions for preventing burnout, reducing turnover, and increasing client care.

This research is important because not only does it support caregivers but also allows a place to go to escape from the day-to-day stressors. It allows the clients to explore their senses while engaging in new and/meaningful occupations. Occupational Therapy helps individuals across the lifespan engage in meaningful and purposeful activities. The occupational therapy profession targets a complexity of factors underlying successful engagement in occupation, such as motivation, cognition, activity demands, human capacity, and environment, to understand how to help increase individuals’ participation in meaningful occupations and increase overall quality of life [26]. Offering care to the community demonstrates a professional commitment and dedication to improving the ability for all to function in their desired occupations. While providing support to caregivers/staff and clients by carefully designing and building a sensory garden students are executing the American Occupational Therapy Association’s [26] core values of altruism and justice.

Competing Interests:

The authors of this research declare no competing interest regarding this study.

List of Abbreviations

Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI)

References

Lee, K., Cascella, M., Marwaha, R., (2025). Intellectual Disability. [Updated 2023 Jun 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. View

Patel, D. R., Cabral, M. D., Ho, A., Merrick, J. A., (2020). clinical primer on intellectual disability. Transl Pediatr. 9(Suppl 1):S23-S35. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.02. PMID: 32206581; PMCID: PMC7082244. View

Parsons, M. B., Reid, D. H., Towery, D., England, P., Darden, M., (2008). Remediating minimal progress on teaching programs by adults with severe disabilities in a congregate day setting. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 1: 59–67. View

Rowles, G. D., & Teaster, P. B. (2015). Long-term care in an aging society: Theory and practice (1st ed.). Springer Publishing Company. View

Ryan, C., Bergin, M., & Wells, J. S. G. (2021). Work-related stress and well-being of direct care workers in intellectual disability services: A scoping review of the literature. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 67(1), 1–22. View

Finn, L. L. (2020a). Improving interactions between parents, teachers, and staff and individuals with developmental disabilities: A review of caregiver training methods and results. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 66(5), 390–402. View

Friedman, C. (2020). The impact of direct support professional turnover on the health and safety of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Inclusion. Advance online publication. View

Finn, L. L. (2020b). Improving quality of life through caregiver training and support. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 66(5), 327–329. View

Duncan, S., Hinckson, E., & Souter-Brown, G. (2021). Effects of a Sensory Garden on Workplace Wellbeing: A Randomized Control Trial. Landscape and Urban Planning, 207. View

G N, Nagajyothi. (2023). Sensory Garden: An Emerging Trend. View

American Heart Association (2024). Spend Time in Nature to Reduce Stress and Anxiety View

Burton, A. (2014). Gardens that take care of us. The Lancet, 13(5), 447-448. View

Thrive. Sensory Gardens. View

Gerdes, M. E., Aistis, L. A., Sachs, N. A., Williams, M., Roberts, J. D., and Rosenberg Goldstein, R. E. (2022). Reducing anxiety with nature and gardening (RANG): Evaluating the impacts of gardening and outdoor activities on anxiety among U.S. adults during the Covid-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:5121. View

Cordoza, M., Fitzpatrick, P. S., Gardine, S. K., Hazen, T. M., Manulik, B. J., Mirka, A., Perkins, R. S., & Ulrich, R. S. (2018). Impact of Nurses Taking Daily Work Breaks in a Hospital Garden on Burnout. American Journal of Critical Care, 27(5), 508–512. View

Vujcic, M., Tomicevic-Dubljevic, J., Grbic, M., Lecic-Tosevski, D., Vukovic, O., and Toskovic, O. (2017). Nature based solution for improving mental health and well-being in urban areas. Environ. Res. 158, 385–392. View

American Network of Community Options and Resources. (2014). Ensuring a sustainable work force for people with disabilities: Minimum wage increases cannot leave direct support professionals behind. View

Keesler, J. M., & Troxel, J. (2019). They care for others, but what about themselves? Understanding selfcare among DSPs’ and its relationship to professional quality of life. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Advance online publication. View

American Psychological Association (APA, 2017). Ethical principles of psychologist and conduct. APA Publishing. View

William, S. G., Fruh, S., Barinas, J. L., & Graves, R. J., (2022). Self-Care in Nurses. J RadiolNurs. 41(1):22-27. doi: 10.1016/j. jradnu.2021.11.001. Epub 2021 Dec 31. PMID: 35431686; PMCID: PMC9007545.View

Coates, D. D., & Howe, D., (2015). The design and development of staff wellbeing initiatives: staff stressors, burnout and emotional exhaustion at children and young people's mental health in Australia. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 42, 655–663. View

Baker, P., et al., (2024). A Systematic Review of Burnout Amongst Staff Working in Services for Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 38(1). View

Weigl, M., Schneider, A., Hoffmann, F., et al., (2015). Work stress, burnout, and perceived quality of care: a cross-sectional study among hospital pediatricians. Eur J Pediatr. 174(9):1237-46. View

Lin, D. J., Finklestein, P. S., Cramer, S. C.,(2018). New Directions in Treatments Targeting Stroke Recovery. Stroke. 49(12):3107-3114. View

Finklestein, P. S., Lin,D. J., Cramer, S. C., (2018). New Directions in Treatments Targeting Stroke Recovery. Stroke. 49(12):3107-3114. View

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). AOTA 2020 occupational therapy code of ethics. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl. 3), 7413410005. View