Journal of Rehabilitation Practices and Research Volume 6 (2025), Article ID: JRPR-158

https://doi.org/10.33790/jrpr1100158Research Article

Faculty Investment in Mentoring and Professional Development of the Student Physical Therapist: Coaching an Interprofessional Team

Allan Dunlap, Sabrina Pennington, Cleve Carter, and Veronica Jackson*

Department of Physical Therapy, Alabama State University, College of Health Sciences,United States.

Corresponding Author Details: Veronica Jackson, Associate Professor, Department of Physical Therapy, Alabama State University, College of Health Sciences, United States.

Received date: 12th November, 2024

Accepted date: 14th February, 2025

Published date: 24th February, 2025

Citation: Dunlap, A., Pennington, S., Carter, C., & Jackson, V., (2025). Faculty Investment in Mentoring and Professional Development of the Student Physical Therapist: Coaching an Interprofessional Team. J Rehab Pract Res, 6(1):158.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

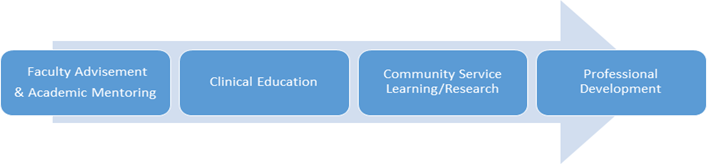

Faculty mentoring and professional development of students is essential for graduating well-rounded, culturally sensitive, ethical practicing healthcare providers. Mentoring and professional development of the student physical therapist are imperative to meet the healthcare needs of a diverse population of modern-day society. Student physical therapists with professional developmental experiences can be a valuable and positive way of assisting students in their growth and development as allied health professionals. This paper explores the four core principles of faculty investment in the professional development of student physical therapists in higher education: (1) mentorship and advisement, (2) professional development, (3) clinical education experiences, and (4) service-learning research opportunities. This can be a time-consuming commitment on the part of faculty members. However, these activities lead to meeting the mission of higher education like creating a nurturing learning environment that develops students to be global change agents. It also embraces philanthropy and creates positive community impact.

Keywords: Faculty Advisement, Professional Development, Interprofessional Collaboration, Student Physical Therapist

Introduction

Student physical therapists (SPT) will work with diverse patient populations in the United States where, according to the US census [1], the current population is 334, 914, 895, and growing into even more diverse group with black or African American (13.7%), Hispanic and Latino (19.5%), Asia (6.4 %), Native Alaskan and American Indian (1.3%), and two or more races (3.1%). To effectively serve this diverse patient population, the SPT would benefit from being equipped with professional behaviors to function within this population, which requires faculty mentorship and advisement, professional development, clinical education experiences, and service-learning opportunities that allow students to practice professional behaviors. Professional behavior feedback is essential to student development. Riopel et al. [2] suggested that cultivation of professional behaviors can be accomplished by the use of standardized patients, which can facilitate a learning dialogue between student and faculty about their behaviors. In this study, seeing through the patient’s eyes; the use of standardardized patients offer unique contributions to student learning; timely, verbal feedback adds a deeper understanding of professional behaviors in preparation for the clinic; and verbal feedback promotes student self-efficacy of professional behaviors. This is one way faculty can work together to cultivate the professional development of the SPT in becoming a well-rounded interdisciplinary healthcare team member.

Collaboration is crucial at all levels within the allied health professions. Kaiser et al [3] stated that interprofessional collaboration (IPC) is seen as the "gold standard" of comprehensive care. Schot et al. [4] asserted there is considerable evidence for professionals actively contributing to interprofessional collaboration in three distinct ways: by bridging professional, social, physical and task-related gaps, by negotiating overlaps in roles and tasks, and by creating spaces to be able to do so. Although the evidence on the importance of collaboration between allied health educators needs to be further documented, collaborative efforts between healthcare professionals is a value that should be demonstrated in both the halls of academia and field of work. Collaboration between health professions holds significant importance in fostering comprehensive education, interdisciplinary understanding, and holistic patient care [5,6]. By working together, educators from various allied health disciplines, such as physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and nursing, can pool their expertise and resources to enhance the educational experience for students and promote better outcomes for patients. Schot et al. [4] expressed that working interprofessional implies an integrated perspective on patient care between workers from different professions involved. Working collaboratively implies smooth working relations in the face of highly connected and interdependent tasks.

Among allied health educators, collaboration promotes interdisciplinary understanding and teamwork among students. By exposing students to diverse perspectives and approaches to patient care, educators can help them develop a more comprehensive understanding of healthcare delivery and the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration [5,7]. This prepares students to work effectively within multidisciplinary teams, ultimately improving patient outcomes through coordinated care. Ratna [8] asserted that, workers of varying skillsets within a healthcare setting must communicate clearly with each other to best coordinate care delivery to patients. This coordinated care involves a critical arm of effective communication, which is central to having optimal patient interventions and outcomes with staff members, the patient, and patient family members. SPTs and their academic advisors and mentors can spend time in conversation about the importance of being able to communicate with all parties involved in case management of patient care.

Secondly, collaboration facilitates the sharing of best practices and innovative teaching strategies among allied health educators. According to Shakham et al. [5] currently, various accrediting bodies, standards, and guidelines require health professionals to promote IPE in undergraduate education. IPE is promoted in pharmacy, dentistry, medicine, nursing, and other allied health professions.

By collaborating on curriculum development, instructional techniques, and assessment methods, educators can leverage each other's strengths and expertise to create more engaging and effective learning experiences for students. This collaborative approach helps ensure that educational programs remain current, evidence-based, and aligned with evolving healthcare trends and standards. Additionally, collaboration among allied health educators strengthens the integration of interprofessional education (IPE) into healthcare curricula and encourages mentoring among healthcare educators. IPE emphasizes the importance of collaborative practice and communication among healthcare professionals from different disciplines to optimize patient care [7]. By collaborating on IPE initiatives, educators can design meaningful learning experiences that promote teamwork, communication skills, and mutual respect among future healthcare professionals.

Furthermore, collaboration among allied health educators fosters a culture of continuous learning and professional development. According to Sherman et al. [9] through interprofessional education and training, health professionals may come to recognize shared values and codes of conduct and move from a sense of independence to interdependence to provide patient-centered, holistic health care. By engaging in collaborative research projects, attending interdisciplinary conferences, and participating in cross-disciplinary training opportunities, educators can expand their knowledge base, stay abreast of emerging trends and technologies, and enhance their teaching effectiveness [10]. This ongoing collaboration helps ensure that educators remain innovative, motivated, and equipped to prepare students through advisement and mentorship for success in their respective allied health professions.

Collaboration among allied health educators is essential for promoting interdisciplinary understanding, sharing best practices, integrating interprofessional education, and fostering continuous learning and professional development. According to Sherman et al. [9], the WHO framework not only identified mechanisms to shape successful teamwork but also outlined actions to be applied in academic and healthcare systems. In accordance with the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC), faculty in Colleges of Health Professions were encouraged to develop core competencies for collaborative practice in all professional curricula. Such core competencies would embed essential content of interprofessional communication, patient-family centered care, role clarification, collaborative leadership, and conflict resolution. Academic advisors and mentors can use this framework to teach student interns these basic foundational principles of interprofessional teamwork.

By working together, educators can enhance the educational experience for students and ultimately improve patient care outcomes through effective interdisciplinary collaboration towards professional development. Schot et al. [4] asserted that there can be certain types of gaps professionals are observed to bridge which is social. Working together can require communicating cautiously or strategically in the light of diverse personalities and communication preferences. The principles of faculty mentorship and advisement, professional development, clinical education experiences, and service-learning underscore adherence to professional standards of conduct of student physical therapist within a social healthcare environment. This promotion of professional development, that can be time-consuming on the part of faculty and clinicians, can lead to a positive organizational climate, a respect for leadership, and collaborative engagement in the academic and clinical settings. According to Burgess et al. [11] mentoring involves both a coaching and an educational role, requiring a generosity of time, empathy, a willingness to share knowledge and skills, and an enthusiasm for teaching and the success of others.

Academic Mentoring & Faculty Advisement

Mentorship is a major key to success in pre-professional training. It requires a commitment to studying and mastering the volume of material necessary to obtain a professional degree. The mentor must have frequent and coordinated check-ins with the mentee. Talking over the material with a mentor has to involve bridge building and confidence in one’s ability to learn. Burguss et al. [12] emphasized that health professionals are not only expected to teach their peers and juniors within their own disciplines, but also across a range of health disciplines. Skills in supervision, teaching, facilitation, assessment and feedback, leadership and interprofessional teamwork are required graduate attributes for health professionals. Hill et al. [13] asserted that mentoring has a long tradition in academic health centers, and from an institutional perspective can positively impact retention, wellness, promotion success, work satisfaction, and more. Hill et al states, “throughout the history of academic health centers, mentoring has been a vital element for interprofessional faculty growth and development. It is a teaching and learning opportunity for the mentor and mentee alike and can serve to increase professional and personal satisfaction for both participants (p. 1)” Mentoring can serve to create a nurturing environment. Most programs require students to meet with academic advisors at least once a semester to hold students accountable for any individualized contract set in place to assist the student in meeting goals for passing academic coursework.

Students require academic advisement and mentoring for a wide range of issues. One of the most recent issues is the use of social media while working within a clinical setting and what is and is not appropriate, using appropriate language of addressing client, and mental health issues with burnout and depression. Kowtko and Watts [14] reported favorable outcomes for their students involved in mentoring relationships, such as decreased stress and anxiety about their education, increased feelings of belonging to their programs and professions, and increased self-confidence and self-esteem. According to Scott [15] the National Institute of Mental Health, anxiety is one of the most common forms of mental illness, with an estimated 31.1% of adults in the United States experiencing any anxiety disorder at some time in their lives. Anxiety is especially prevalent and is the leading cause of mental health issues and psychological distress among the college-aged population, due to differing stressors that college students encounter such as geographic change, academic challenge, financial strain, and a new social environment. Faculty advisement and mentoring is the how and why of professional development of our students. Students do not always know how to navigate a curriculum and will therefore make mistakes. Mentoring is how restoration begins. They do not always know the safe route to accomplishing a goal or task and will need direction on the route that should be taken. Having a faculty advisor to getting there safely and without undue cost to career and academic acumen. The faculty advisor takes the lead in that journey but eventually hands it off to the student. Kowtko and Watts [14] asserted that mentoring also assists with easing the transition from student to graduate in a shorter period.

Mentorship is the act of guiding, directing and influencing one down a particular path, toward a specific goal, or assisting with the attainment of an achievement. Mentorship can be further described as a professional working partnership that supports the personal and professional growth, development, and success of both the partnership and the involved individuals. Mentorship fosters personal growth, enhances clinical skills, and promotes career advancement, ultimately contributing to the overall quality of patient care and the advancement of both the individual allied health professionals and health professions. Burgess et al. [16] suggested that some of the skills needed to teach peers is to provide clarity to explanations given, has good rapport and shows respect to students, stimulates interest, up to date on currents practices, provides feedback, positive reinforcement, and demonstrates clinical competence.

Mentors serve as a role model or guide for their mentee’s behavior, values, and attitudes by being a source of inspiration, and helping their mentee navigate the complexity of their chosen profession, while overcoming obstacles and developing confidence [17]. Mentees benefit from engaging with a mentor who has a deep-level similarity with them including similar values. This allows mentees to see themselves as future academics. Through mentorship, mentees can gain valuable clinical knowledge, refine their critical thinking skills, and cultivate the professional attributes necessary for effective practice [17]. This transfer of knowledge not only enriches the learning experience for mentees but also ensures the preservation and dissemination of best practices within allied health professions.

Furthermore, mentorship contributes to the retention and professional satisfaction of allied health professionals [13]. Mentees who receive ongoing support and encouragement from mentors are more likely to feel valued, engaged, and fulfilled in their careers. Mentors help mentees set goals, identify career pathways, and navigate professional challenges, thereby increasing job satisfaction and reducing burnout [18]. Becoming a mentor is easy, being an effective mentor who truly works to make a difference requires tenacity. An effective mentor displays trustworthiness, passion, enthusiasm and can give constructive and honest feedback without imposing judgment [17]. By investing in mentorship, healthcare organizations can cultivate a culture of support and growth that attracts and retains top talent, ultimately benefiting both individual practitioners and the broader healthcare system [13].

Mentorship is of paramount importance in the allied health professions, providing invaluable support, guidance, and professional development opportunities for students and early-career professionals [17]. Mentorship fosters a sense of belonging and community within the allied health professions. Mentees benefit from the guidance and support of their mentors, who provide encouragement, advocacy, and networking opportunities. Through mentorship, practitioners can enhance their clinical skills, advance their careers, and ultimately contribute to the delivery of high-quality patient care. By investing in mentorship, healthcare organizations can cultivate a vibrant and skilled workforce that is well-equipped to meet the evolving needs of patients and communities [11,13].

Academic advisors can advocate for students becoming a partprofessional networks. According to Cline et al. [19] professional organizations offer numerous benefits, including continuing education, professional publications, networking, and a platform for engagement in clinical, political, and regulatory activity. Professional networks serve as groups of individuals connected through professional relationships and interactions, typically within a specific industry or field, can also further develop mentoring relationships. Indar et al [20] suggest that health system transformation requires the collaborative efforts of a large swath of macro-, meso- and micro-level actors, which often include government, professional associations, organizations, health care providers and many others. These connections are established and maintained for the purpose of sharing information, resources, advice, and opportunities. Professional networks can include colleagues, mentors, industry experts, former classmates, and other professional contacts. They are crucial for career development, providing support, facilitating knowledge exchange, and opening doors to new job opportunities, collaborations, and advancements. Professional networks can be built and expanded through various means, such as attending industry conferences, participating in professional organizations, engaging on social media platforms like LinkedIn, and through every day professional interactions. Cline et al [19] conclude that professional association memberships provide an opportunity for professional growth. These memberships often come with continuing education opportunities, discounted certification examination costs, reduced conference fees, and subscriptions to peer-reviewed publications. These all can contribute to the maintenance of licensure and to keeping up-to-date with the most current evidence to support practice.

Clinical Education

According to the American Council of Academic Physical Therapy [21], a clinical education experience helps students to demonstrate competence before beginning independent practice. According to Riopel et al [2] clinical instructors have identified several concerns with the professional standards demonstrated by PT students, including inappropriate personal behavior, inappropriate interactions with patients or colleagues, inappropriate responses to feedback, and failure to accept responsibility for unprofessional behaviors. Aljohani et al. [22] concluded that academic advisement was found to be important among students, reporting that students knew their advisers and met with them at least once a year. The social role of academic advising was perceived as its most important function followed by the personal role.Academic advisement, faculty mentoring, and professional development related to these types of issues is essential for student matriculation and growth in clinical education. Riopel et al. [2] suggested that providing direct feedback about professional behaviors is an effective way to facilitate such behavioral changes. This coaching approach between the SPT, faculty, and clinicians is an effective way to train SPT. Black et al. [23] reported that coaching programs were effective and supported a sense of belonging or connectedness within their DPT program. While much of the academic mentoring and professional development happens at the direction of faculty within educational settings, the clinical education requirement happens within professional healthcare environments, where the dent Physical Therapist can benefit from understanding what professional behaviors look like in a business healthcare model setting. In this setting, the ultimate goal is to demonstrate acceptable professional behaviors that yield excellent patient outcomes.

Student physical therapists view themselves as consumers of the academic institution and their primary interest is student-centered. However, when matriculating to a professional clinical setting, students must shift this interest to one that is patient-centered and places another person's needs as the primary concern. According to CAPTE [24], Clinical Instructors the physical therapy student and for directing, instructing, guiding, supervising, and formally assessing the student during the clinical education experience. Clinical Instructors model professional behaviors in the clinical setting that are reinforced by what students have been exposed to and taught in the classroom by their faculty. The clinical setting provides the SPT with “real” patient interactions that allows them to demonstrate professional behaviors and to see how they can contribute to making a positive impact on patients and the community.

The clinical environment brings to life the emerging needs of the patient which the student must respond to during interactions with patients, caregivers, and other healthcare providers. Schot et al. [4] asserted that interprofessional collaboration is often equated with healthcare teams and is often established within healthcare as an active and ongoing partnership between professionals from diverse backgrounds with distinctive professional cultures and possibly representing different organizations or sectors working together in providing services for the benefit of healthcare users. These interactions allow the SPT to see firsthand what appropriate professional behaviors look like in licensed healthcare professionals. The APTA Code of Ethics for Physical Therapist [25] delineates the ethical obligations, professional behaviors, and standards of practice that provide appropriate guidance for SPT. So then, faculty mentoring and professional development is carried over from the academic setting to the clinical setting using the Clinical Instructor as a model of upholding professional behavior. The CI, in direct contact with the SPT, can then mentor the student on their clinical performance and provide appropriate and relevant feedback needed for professional growth and development.

In order for the SPT to become change agents they must model professional behaviors that include ethical and legal practice, self-assessment, interpersonal communication, and making good clinical decisions. Students will operate in different inpatient and outpatient clinical practice settings and will need to understand their role within these settings.

Ethical and legal practice is at the forefront in a clinical practice setting and part of the core values. According to the APTA Core Values [26] a practicing therapist displays behaviors that encompass: accountability, altruism, collaboration, duty, caring, compassion, excellence, inclusion, and integrity. Ethical standards are based on human rights and wrongs while legal standards are based on the law. It is important for students to know the difference and witness modeled behavior in the clinical setting. Some basic principles include providing appropriate therapy services that are needed and beneficial to the patient, with dignity and respect for patient rights. It is also imperative for SPT to understand insurance and record appropriate charges for treatments.

Self-Assessment allows for the SPT to do a reflection of his or her professional and clinical behaviors. According to the APTA Core Value Self- Assessment [27] students are engaged in self-assessment reflecting over the seven core behaviors adopted as essential to professionalism as they interact with others in the academic and clinical settings. This assessment is useful in providing definitions of core values as well as sample indicators to guide students through their self-assessment. Professional growth only comes with self-assessment with appropriate and relevant feedback from academic and clinical education faculty. Additional opportunities will allow students to grow in areas that need improvements. Professional growth is also noted when SPT gain the ability to recognize when to make referrals when treatment is out of the scope of the professional, using evidence-based research to guide clinical decisions, and demonstrates their ability to effectively teach and share their knowledge with others.

Interpersonal communication is crucial for SPT to being the change agents needed in a diverse global society that is culturally sensitive. Ratna [8] stated that, “effective communication is of the utmost importance when delivering healthcare. Without it, the quality of healthcare would be impaired. Healthcare costs and negative patient outcomes would increase. There are multiple components to effective communication in a healthcare setting: healthcare literacy, cultural competency and language barriers. If any one of these components is compromised, effective communication does not occur.” As academic and clinical mentors, students in the allied health professions can benefit from understanding communication dynamics and how a lack of effective communication can directly affect patient outcomes.

Student physical therapists must use effective verbal and non-verbal professional interpersonal communication with co-workers, patients, and family members to enhance good patient outcomes. The APTA Clinical Performance Instrument (CPI) 3.0, [28] measures this ability to communicate effectively within a clinical setting with all stakeholders. Student physical therapists will contact other healthcare professionals directly in case management meetings, reporting on patient progress, equipment needs, and other pertinent information. They will also communicate with family members, provide patient education on safety measures, and educate the family on therapeutic exercise. They will also be communicating with family members, providing patient education on safety measures, and educating the family on therapeutic exercise. Tag mentoring and collaboration with faculty advisors will assist in reinforcing healthy professional behaviors between student physical therapist and clinical instructors.

Student physical therapists also need the skill of making good clinical decisions. The APTA CPI 3.0 [28] examines the student clinical performance in making competent clinical decisions related to patient care. After conducting an examination student needs to be able to gather, interpret, and synthesize information relevant to patient care from multiple sources. According to Shakhman et at. [5] different theoretical frameworks guide IPE. These include adult learning theory, Bernstein’s sociological theory, and social capital theory. All theories are centered on the needs of patients and help in creating interprofessional learning networks and the content of interprofessional curricula. Using these theories, healthcare practitioners can develop innovative IPE and practice innovations for students that span theoretical and clinical experiences.

To make good clinical judgments, consultation with stakeholders to generate other alternative options to confirm best practices related to good clinical decisions related to patient care. The competency of these professional clinical practices demonstrated through clinical education experiences by students lead to the adoption of professional development. Students should be motivated to take on leadership opportunities to continue a career path of professional development. Self-Assessment is a key component in professional development of SPT. Scott [15] asserts that clinical experiences, time management, coping strategies, social support, and academic performance were all found to be risk factors associated with student’s anxiety. Faculty academic and clinical advisement coupled with mentoring can benefit interns related to these factors to help cope with these potential stressors.

Community Service/Service-Learning Research

Community service and service-learning projects can serve to expose SPT to the lay public in being able to practice their professional behaviors like communication, care, and compassion. Some of these service events may include conducting health fairs, providing health & wellness education to community agencies, or working with a food bank. The development of effective communication skills is imperative to the development of scholarship and research. According to Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM) (2024) scholarship and research are closely related concepts in academia. Merriam Webster’s dictionary [29] described research as “careful study that is done to find and report new knowledge about something,” while scholarship is defined as “serious formal study or research of a subject.” While these terms appear similar at the surface, they differ in their scope and focus. Research typically refers to systematically investigating and studying a particular topic, issue, or problem to generate new knowledge, insights, or solutions. It often involves empirical inquiry, data collection, analysis, and the testing of hypotheses to contribute to the existing body of knowledge within a specific field or discipline. Faculty mentorship can serve to facilitate student involvement into the research process and understanding the differences between scholarship and research. This experience can also motivate and inspire SPT to become academicians.

On the other hand, scholarship encompasses a broader range of intellectual activities beyond original research, including the critical analysis, interpretation, synthesis, and dissemination of knowledge [30]. This experience can be beneficial to the SPT by modeling how to conduct research, interact with the literature, and understand the importance and value in the dissemination of new information related to the improvement of patient outcomes. Scholarship may involve activities such as literature reviews, theoretical analysis, commentary, critique, and creative expressions that contribute to the advancement and understanding of a particular subject area. While research is a subset of scholarship, scholarship encompasses a wider spectrum of intellectual engagement that includes research as one of its components [31].

According to the Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education (CAPTE), standards require interdisciplinary experiences for SPT, which is a valuable experience for professional development. This experience allows SPTs to develop relationships with other healthcare providers, learn and value their contribution, and gain the ability to be better equipped to make referrals. Research on interdisciplinary approaches to healthcare indicates several significant benefits, including improved patient outcomes, enhanced care quality, increased patient satisfaction, and more efficient use of resources [32,33]. Interdisciplinary teams, composed of various healthcare professionals such as doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers, are shown to enhance patient outcomes, particularly in chronic disease management where coordinated care effectively manages conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and mental health disorders. The diverse expertise in these teams leads to comprehensive care plans that address multiple aspects of a patient’s health, reducing the likelihood of errors and omissions, and ensuring care that is more holistic, and patient centered.

Patients often report higher satisfaction levels when cared for by an interdisciplinary team. Patients appreciate the coordinated approach and comprehensive care, which includes better communication and more personalized attention. Additionally, interdisciplinary care can lead to more efficient use of healthcare resources by reducing duplicate tests and procedures, and improving coordination and communication among healthcare providers, thereby reducing costs without compromising care quality [34]. Healthcare providers in interdisciplinary teams also report higher job satisfaction due to the collaborative environment, which fosters mutual respect and professional growth, while reducing burnout and improving retention rates among healthcare workers [35].

Despite these benefits, there are challenges to implementing an interdisciplinary approach. These challenges include logistical issues such as coordinating schedules and communicating with team members. Other challenges include organizational barriers such as team members' resistance to change and/or lack of support from leadership. Research shows that certain populations, such as the elderly, those with complex or multiple health conditions, and patients in palliative care particularly benefit from an interdisciplinary approach. This approach is most effective in settings like primary care, hospitals, and community health centers. Studies published in the Journal of Interprofessional Care, New England Journal of Medicine, and American Journal of Managed Care highlight the positive impacts of interdisciplinary teams on chronic disease management, patient satisfaction, cost savings, and improved efficiency. The evidence strongly supports adopting an interdisciplinary approach in healthcare; however, successful implementation requires addressing associated challenges through organizational support, training, and effective communication strategies.

These communication strategies begin through the assignment of a faculty research advisor to discuss development of research agendas for research and capstone projects. This relationship enables students to learn about research discovery, how to conduct literature reviews, learning how to develop methodology, and how to coordinate a research presentation.

Professional Development

Professional development (PD) is an ongoing process that enables professionals to acquire new knowledge, skills, and attitudes to stay relevant and excel in their fields. PD serves a critical purpose for both individuals and organizations. According to Collins [36], the goal of PD is to support the lifelong learning of professionals by enabling them to adapt to the ever-evolving workplace. PD enhances individual competencies and boosts the overall quality of service and productivity within organizations. Henry-Noel [18] suggested that mentors can be instrumental in conveying explicit academic knowledge required to master curriculum content. They can enhance implicit knowledge about the "hidden curriculum" of professionalism, ethics, values, and the art of medicine not learned from texts. In many cases, mentors also provide emotional support and encouragement in the process of professional development.

The primary purpose of PD in physical therapy is to equip practitioners with the latest knowledge, skills, and evidence-based practices to provide high-quality patient care and remain competent and competitive in their fields. PD supports the ethical responsibility of physical therapists to provide the best possible care by continually improving their competency. Filipe et al. [37] highlight, one of the significant purposes of PD is to foster adaptability and resilience in professional. In today's fast-paced and technology-driven world, professionals must be able to keep pace with advancements in their industries. Whether acquiring new technical skills, enhancing leadership abilities, or staying updated on regulatory changes, professional development is critical in maintaining high standards in any career.

Professional development for physical therapists can take many forms, from formal education to informal networking opportunities. Attending workshops, seminars, and conferences are common forms of PD. These opportunities allow therapists to stay informed about new research, techniques, and trends in the field. For example, many physical therapy organizations, such as the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA), offer annual conferences that feature educational sessions, hands-on workshops, and opportunities to network with other professionals. For students, PD often begins with participating in clinical rotations, attending guest lectures, and engaging in research opportunities. Additionally, many physical therapy programs encourage or require students to attend professional conferences, which provides them with valuable networking opportunities and exposure.

Organizations also play a crucial role in promoting PD. Organizations often provide or encourage employees to participate in PD activities by offering various incentives such as, financial support for certifications, hosting in-house training, and providing access to professional networks. According to Filipe et al. [37], fostering a culture of professional growth within an organization is essential to remain competitive in today’s globalized workforce. Moreover, supporting PD initiatives such as research opportunities or leadership roles within organizations helps professionals expand their horizons and take on more responsibilities.

Professional development is an ongoing journey that is vital for personal and career success. In the rapidly changing healthcare landscape, staying current with best practices is not just beneficial— it is essential. By taking advantage of PD opportunities, whether through conferences, research, or leadership roles, we can continuously improve our skills and remain adaptable to the evolving needs of our professions. As APTA [38] noted, lifelong learning is not only a personal responsibility but a professional obligation. Through this commitment, we can ensure that we provide the highest level of care to our patients and contribute meaningfully to our fields.

Practical Application

The elements of professional development are multifaceted and requires mentorship and advisement. Professional programs of health sciences commonly assign students a faculty advisor that are the starting point to developing a relationship with the student. Basic information related to study habits, commitment, and time management are discussed as the relationship between faculty member and student begins to develop. Faculty advisement is then paired with academic mentorship. Faculty members encourage students to seek out mentors that they may have previously known or can make mentor recommendations to students. As students matriculate through professional programs other opportunities arise like attending professional conferences, where students are able to meet other healthcare professionals and to network with potential employers. Clinical education plays a major role in the professional development of students, as students are assigned clinical instructors to assist in their professional development. The planning and coordination of community service-learning events gives students the opportunity to engage with members of the community and to use skills learned to further bring about professional development. Research also engages students in the professional development of becoming collaborative healthcare team members in an interprofessional environment where patients will receive care. Faculty advisement, academic mentorship, clinical education, community service learning, and research engagement contribute to the overall professional development of student healthcare professionals.

Conclusion

Overall, mentorship and advisement, clinical education experiences, and service-learning research opportunities can lead to the professional development of a well-rounded SPT. Mentorship and advisement means having a lot of conversations with SPT about behaviors, study skills, appropriate attire, grades, credits, and other conflicts they may experience. Student Physical Therapist experience financial burdens, death of loved ones, caring for loved ones who are sick, and at times their own health issues. This climate of mentorship and advisement also allows faculty to interject solutions to other problems like managing a heaving reading load, identify the need for tutorial, dealing with family issues, and making accommodations for someone identified as being diagnosed with anxiety.

Mentorship and advisement can turn into a positive outlet for the SPT, in order for the faculty member to redirect and encourage the SPT in making good decisions. This relationship then becomes easy to mentor and direct the SPT in other areas like clinical decision making, the development of a research agenda, and service to the community. These conversations and experiences faculty create for for the SPT encourage students to reconnect with their own self-resilience and self-confidence, which are essential for success in becoming a licensed physical therapist. This experience of faculty mentorship and advisement can have a positive effect towards professional development of the student physical therapist.

Professional development is an integral aspect of a successful career in physical therapy that starts with faculty mentorship promoting the importance of professional behaviors. By staying informed and engaged through workshops, research opportunities, and interprofessional collaborations, students and practicing physical therapists can ensure that they deliver the highest standard of care. PD enhances personal career satisfaction and improves the overall quality of patient care, benefiting the profession.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

"U.S. Census Bureau (2022). Race and Hispanic Origin, 2018- 2022. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/ table/US/HSD410222#HSD410222 View

Riopel, M. A., Litwin, B., Silberman, N., & Fernandez, A. (2019). Promoting Professional Behaviours in Physical Therapy Students Using Standardized Patient Feedback. Physiotherapy Canada. Physiotherapie Canada, 71(2), 160–167.View

Kaiser, L., Conrad, S., Neugebauer, E. A. M., Pietsch, B., & Pieper, D. (2022). Interprofessional collaboration and patient reported outcomes in inpatient care: a systematic review. Systematic reviews, 11(1), 169. View

Schot, E., Tummers, L., & Noordegraaf, M. (2019). Working on working together. A systematic review on how healthcare professionals contribute to interprofessional collaboration. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(3), 332–342. View

Shakhman, L. M., Al Omari, O., Arulappan, J., &Wynaden, D. (2020). Interprofessional Education and Collaboration: Strategies for Implementation. Oman medical journal, 35(4), e160. View

Bendowska, A., & Baum, E. (2023). The significance of cooperation in interdisciplinary health care teams as perceived by polish medical students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 954. View

Zechariah, S., Ansa, B. E., Johnson, S. W., Gates, A. M., & Leo, G. D. (2019). Interprofessional education and collaboration in healthcare: An exploratory study of the perspectives of medical students in the united states. Healthcare (Basel), 7(4), 117. View

Ratna, H. (2019). The importance of effective communication in healthcare practice. Harvard Public Health Review. 23. View

Sherman, E. M.S., Slick, D. J., Iverson, G. L., (2020). Multidimensional Malingering Criteria for Neuropsychological Assessment: A 20-Year Update of the Malingered Neuropsychological Dysfunction Criteria. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 28;35(6):735-764. View

Pischetola, M., Møller, J. K., & Malmborg, L. (2023). Enhancing teacher collaboration in higher education: The potential of activity-oriented design for professional development. Education and Information Technologies, 28(6), 7571-7600. View

Burgess, A., Diggele, C., & Mellis, C. (2018). Mentorship in the health professions: A review. The Clinical Teacher, 15(3), 197- 202. View

Burgess, A., van Diggele, C., Roberts, C. et al. Key tips for teaching in the clinical setting. BMC Med Educ 20 (Suppl 2), 463 (2020). View

Hill, S. E. M., Ward, W. L., Seay, A., &Buzenski, J. (2022). The nature and evolution of the mentoring relationship in academic health centers. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 29(3), 557-569. View

Kowtko, C., & Watts, L. K. (2008). Mentoring in Health Sciences Education: A Review of the Literature. Journal of medical imaging and radiation sciences, 39(2), 69–74. View

Scott, S. A., (2023). Prevalence and Risk Factors for Anxiety in Medical and Allied Health Students in the United States and Canada. The Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice. 21(4), Article 7.View

Burgess, A., van Diggele, C., Roberts, C. et al. Introduction to the Peer Teacher Training in health professional education supplement series. BMC Med Educ 20 (Suppl 2), 454 (2020). View

Germeroth, D., Murray, C. M., McMullen-Roach, S., & Boshoff, K. (2024). A scoping review of mentorship in allied health: Attributes, programs and outcomes. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 71(1), 149-174. View

Henry-Noel, N., Bishop, M., Gwede, C. K., Petkova, E., & Szumacher, E. (2019). Mentorship in medicine and other health professions. Journal of Cancer Education, 34(4), 629-637. View

Cline, D., Curtin, K., & Johnston, P. A. (2019). Professional Organization Membership: The Benefits of Increasing Nursing Participation. Clinical journal of oncology nursing, 23(5), 543– 546.View

Indar, A., Wright, J., & Nelson, M. (2023). Exploring how Professional Associations Influence Health System Transformation: The Case of Ontario Health Teams. International journal of integrated care, 23(2), 19. View

Academic Physical Therapy (2022). Physical Therapy Clinical Education Glossary. https://acapt.org/ glossary#:~:text=Clinical%20Education%20Experience%20 (PT),within%20a%20variety%20of%20environments View

Aljohani, K. A., Almarwani, A. M., Tubaishat, A., Gracia, P. R. B., Natividad, M. J. B., Gamboa, H. M., &Aljohani, M. S. (2023). Health Sciences Students' Perspective on the Functions of Academic Advising. SAGE open nursing, 9, 23779608231172656. View

Black, K., Feda, J., Reynolds, B., Cutrone, G., & Gagnon, K. (2024). Academic coaching in entry-level doctor of physical therapy education. Journal of Physical Therapy Education. View

Commission on Accreditation Physical Therapist Education. (2022). Standards and Required Elements for Accreditation of Physical Therapist Education Programs. View

American Physical Therapy Association. (2020). Code of Ethics for Physical Therapist. View

American Physical Therapy Association. (2021). Core Values for the physical therapist and physical therapist assistant. HOD P09-21-09. View

American Physical Therapy Association. (2013). Core Values Self-Assessment. View

American Physical Therapy Association. (2023). Revised Clinical Performance Instrument 3.0. View

Definition of MENTORSHIP (2019). Merriam-webster.com. Published. View

Hofmeyer, A., Newton, M., & Scott, C. (2007). Valuing the scholarship of integration and the scholarship of application in the academy for health sciences scholars: Recommended methods. Health Research Policy and Systems, 5(1), 5-5. View

Wilkes, L., Mannix, J., & Jackson, D. (2013). Practicing nurses perspectives of clinical scholarship: A qualitative study. BMC Nursing, 12(1), 21-21. View

Johnson & Johnson Nursing. (2024). The importance of interprofessional collaboration in healthcare. Johnson & Johnson Nursing. https://nursing.jnj.com/getting-real-nursing-today/the-importance-of-interprofessional-collaboration-in-healthcare#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThere%20is%20 a%20significant%20amount,and%20interprofessional%20- education%20in%201972. View

Bhati, D., Deogade, M. S., &Kanyal, D. (2023). Improving patient outcomes through effective hospital administration: A comprehensive review. Curēus (Palo Alto, CA), 15(10), e47731-e47731. View

Reeves, S., Pelone, F., Harrison, R., Goldman, J., Zwarenstein, M., & Zwarenstein, M. (2017). Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2018(8), CD000072. View

Bosch, B., & Mansell, H. (2015). Interprofessional collaboration in health care: Lessons to be learned from competitive sports. Canadian Pharmacists Journal, 148(4), 176-179. View

Collin, K., Van der Heijden, B., & Lewis, P. (2012).Continuing professional development. International Journal of Training and Development. 16(3), 155-163. View

Filipe, H. P., Silva, E. D., Stulting, A. A., & Golnik, K. C. (2014). Continuing professional Development Best Practices. Middle East African Journal of Ophthalmology. 21(2), 134– 141. View

American Physical Therapy Association (2022). Professional development and lifelong learning. View