Journal of Rehabilitation Practices and Research Volume 6 (2025), Article ID: JRPR-161

https://doi.org/10.33790/jrpr1100161Research Article

Nicholas D. Wright1*, Angela Merlo, Manuel Romero, R. Nathaniel Foster, Brittany A. Clason

1Department of Kinesiology, California State University, Fresno, Fresno CA, United States.

2Eastern Washington University, Spokane WA

3University of the Pacific, Stockton CA

4Indiana Wesleyan University, Marion IN

5California State University, Fresno, Fresno CA

Corresponding Author Details: Nicholas D. Wright PhD, ATC, SFMA-1, Department of Kinesiology, California State University Fresno, 5275 N. Campus Dr. (M/S SG28), Fresno, CA, 93740.

Received date: 21st January, 2025

Accepted date: 13th March, 2025

Published date: 17th March, 2025

Citation: Wright, N. D., Merlo, A., Romero, M., Foster, R. N., & Clason, B. A., (2025). The Experiences of Collegiate Professors in Providing Academic Accommodations to Students Who Have Suffered a Concussion. J Rehab Pract Res, 6(1):161.

Copyright: ©2025, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Context: Return to Learn is a popular policy that institutions have adopted to help students re-integrate back into the classroom after suffering a concussion. Although a popular policy, and required by some universities, students do not always obtain accommodations for their concussions. While several factors could prevent students from receiving accommodation, one specific cited barrier has been the collegiate professor.

Objective: To investigate the experiences of collegiate professors in providing academic accommodations for students who suffer concussions.

Design: Qualitative study

Patients or Other Participants: Eleven collegiate professors, from two universities, with similar population demographics.

Data Collection and Analysis: Participants choose to participate in one semi-structured interview, focus group, or both, to be recorded and transcribed for inductive coding and thematic analysis.

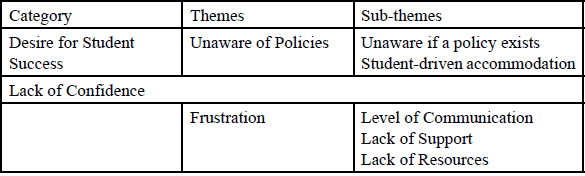

Results: Findings promoted three major themes: Unaware of Policies, Lack of Confidence, and Frustration. Secondary themes identified deficiencies in communication, unprovided resources, and a lack of knowledge of concussion policy. All themes frame the various struggles and frustration professors have experienced when providing accommodations to students suffering a concussion.

Conclusions: College professors are depended on to support their students and provide them with the accommodations they need; however, professors have not had positive experiences when called upon to assist. College professors have not been presented with or made aware of policies and procedures that would assist in providing accommodations to their students. This has led to frustration with the lack of support and lack of communication that would aid their confidence in providing the accommodations necessary for student success.

Key Words: Return to Learn, Identified Policies, Barriers, Frustration

Introduction

A concussion is a traumatic brain injury that occurs either by a direct or indirect blow to the head or neck region, causing rapid acceleration or deceleration to the brain and eliciting neuronal shearing [1-4]. The shearing effect influences a pathophysiological, macrophysical, and psychological response altering regular brain activity, causing a myriad of physical and cognitive symptoms such as headaches, nausea, balance deficiencies, loss of memory, difficulties concentrating, decreased processing speed, and decreased attentional span [1, 5-9]. It is estimated that 1.1 to 1.9 million sportrelated concussions occur annually in the United States; however, this number may underrepresent the true total as concussions are often unreported, go untreated, or are undiagnosed by a healthcare professional [10-12].

Treatment of concussions includes physical rest and cognitive rest followed by a step-wise progressive return to physical activity [1]. Similarly, an equally progressive return to cognitive load is also recommended. This stepwise reintegration to cognitive functioning is known as “return to learn” (RTL) and is a vital protocol for increasing educational success, neural healing, and regaining cognitive functioning [3, 13]. The RTL protocol consists of an individualized plan to progressively re-introduce cognitive activities and responsibilities while carefully monitoring symptoms [13]. For collegiate students, cognitive load modification is monitored through academic accommodations. Academic accommodations can occur at three levels: 1) individual health plans (IHPs), 2) 504 plans, or 3) a formal individualized education plan (IEP) [13]. An IHP is an informal level of support generally put in place by an educator when they observe additional support may be needed in a course. Formal accommodations, or 504 plans, are accommodations given to students with a medical condition or disability that allows the student an equal educational opportunity to participate in the academic program [14]. Finally, IEPs are the most formal and typically involve parent, educator, and administrative support for long-term accommodation needs. Students who suffer a concussion are eligible for any of the three levels of academic accommodations permitting colleges and universities to support the student in their reintegration to full cognitive load [13].

Despite the available accommodations, recommendations, and prevalence of RTL protocols proposed in the literature, RTL policies and procedures are not always created, administered, or followed at collegiate universities [5, 15]. Buckley et al. [15] examined the compliance level of power at five schools in the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) and discovered that while the NCAA requires schools to create an RTL, over a quarter of schools were not in compliance. Furthermore, these discrepancies were reflected in Division II and Division III schools as well [15]. Williamson et al. [16] discovered a disparity in students who suffer a concussion actively receiving accommodations. The disparity has been linked to students declining accommodations for fear of falling behind, feeling a pressure to perform in school, and fear of negative social engagement prompting them to decline the needed accommodations [17, 18]. A major contributor to these barriers is the influence of the college professor. Studies have unveiled the level to which a professor provides support to the student is a major positive or negative stressor for those students while facing their disability [19-21]. Positive support will directly affect the student’s perceptions of their accommodation and can positively address struggles with self-advocacy, injury invisibility, and coursework management.

Managing the cognitive load of a student’s recovery from a concussion is a vital and growing component of the overall care for students who suffer this injury. Recommendations in the literature, requirements from the NCAA, and current educational practice have encouraged Athletic Trainers to create policies and procedures for RTL in addition to RTP. Creation of these RTL policies should be a collaborative approach, valuing the opinions and considerations of all major stakeholders responsible for implementing care for students [22]. Collegiate professors play a direct role in the RTL process as the facilitator of their academic accommodation, an important pillar to facilitate positive outcomes and healing from a brain injury. If collegiate professors are going to be a pillar in the RTL process and trusted to provide necessary accommodations, then their experiences in providing the necessary accommodations in the RTL is a critical phenomenon to investigate.

Methods

Research Design

A two-prong phenomenological approach was used to complete this study. Qualitative semi-structured interviews and a focus group were administered and analyzed to evaluate the experiences of collegiate professors in providing academic accommodations to students who had suffered a concussion.

Participants

Eleven full-time faculty from two different universities were recruited to participate in this study. The two universities were matched based on similar status and demographics. Universities had to be private, four-year universities, located on the west coast, with a student population ranging from 1,000-2,000 students. Professors were included if they were full-time faculty and had experience providing academic accommodations to a student who suffered a concussion. A combination of purposeful sampling and snowball sampling was used to recruit participants. Emails were acquired using the faculty directory on the university’s website and an initial contact email was sent to all faculty containing the recruitment letter and informed consent forms. Faculty were then able to self-select to either the individual one-on-one interview, the focus group, or to both. Participants were accepted into the study until saturation was reached. The study was approved as exempt research by the Rocky Mountain University of Health Professions Institutional Review Board, with additional site approval from the Institutional Review Boards at each participating university.

Data Collection Procedures

All faculty at both universities were sent a recruitment email containing information about the study, IRB and site approval letters, and an informed consent contract. Participants were instructed to respond to the email with their contact information and the preferred interview type they wished to participate in. Once emailed, the principal researcher contacted each participant to discuss the details of the study, check understanding, provide instructions on the informed consent form, and schedule their interview.

Semi-structured Interview

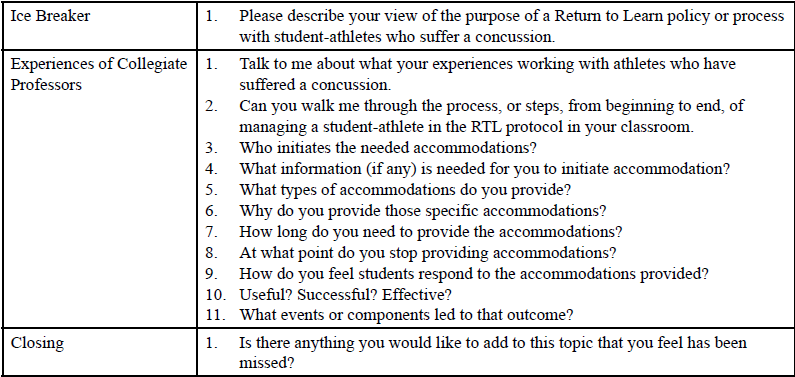

A 13 question semi-structured interview guide was used to gather information on experiences of the participants (see Table 1). Questions included in the interview guide were developed by the principal researcher and reviewed by the other members of the research team before the interview guide was accepted. All interviews were conducted by the principal researcher using Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, Inc, San Jose, CA) and followed a semi-structured interview guide. Audio and visuals from the interviews were recorded and stored for transcription purposes. All interviews were transcribed by the principal researcher and de-identified for anonymity during data analysis.

Focus Group Interview

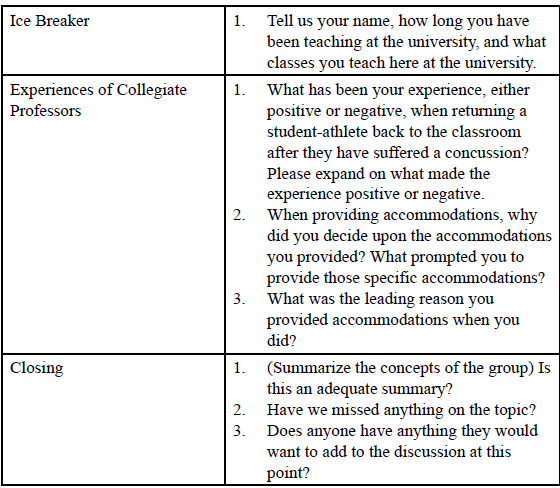

Following the semi-structured interviews, additional questions, based on individual interview results, were added to the focus group interview guide to gain a deeper understanding and context of the data. The final focus group interview guide was reviewed by all members of the research team before implementation (see Table 2). After all one-on-one interviews were complete, participants who self-selected to the focus group were contacted to schedule the focus group. A single focus group, lasting 110 minutes, was conducted with seven members from both universities. The focus group was led by the principal researcher using Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, Inc, San Jose, CA) and followed a semi-structured guide. Audio and visuals from the focus group were recorded and used to create the transcript of the focus group. The transcript was created and deidentified by the principal researcher for the use of data analysis.

Data Analysis and Integrity

The data analysis followed a systematic thematic analysis, outlined by Creswell [23], using a conventional coding method [23]. This method used a line-by-line segmentation process to generate initial codes before combining these codes into overarching themes. This type of process involved several sequences of reading, coding, and analytic thinking before establishing the final codes and theoretical constructs [23]. Line-by-line coding began with an initial reading through the transcript multiple times to gain a general sense of the data and the responses within. The data text was then divided into similar segments of information and assigned a label to describe the text segment. These labeled segments were then combined into similar descriptive groups and attached a code that would accurately reflect the grouping. Codes were then examined analytically and reduced based on redundancy and overlap within the codes. Finally, codes were aggregated into themes. These themes were a representation of the data and used to report our themes passage and narrative story regarding our studied phenomenon.

Several strategies were implemented to establish and enhance the credibility, dependability, transferability, confirmability, and trustworthiness of the analysis. Finalized transcripts were sent to all participants to review, confirm, add, or edit data within the transcript before completing the coding process. Participants were given two weeks to complete a member check; over 60% of participants either confirmed the data or provided edits with the transcript. The data analysis process was triangulated by two additional researchers in conjunction with the principal researcher. An external reviewer with an understanding of the qualitative research process oversaw the coding process by confirming the coding framework, codes, and themes presented by the principal researcher. Additionally, a member of the research team also conferred with the coding process and thematic analysis. Before data collection, the principal researcher participated in reflexivity as described by Creswell [23]. A reflexivity journal was kept to illuminate researcher bias and assumptions, and included rationalizations for the data collection decisions chosen, codes selected, and aggregation decisions that led to the final interpretation of themes [23].

Results

Thematic analysis unveiled that collegiate professors have experienced various levels of barriers, confusion, and frustration when having students who had suffered a concussion. Our findings promoted three major themes: Unaware of Policies, Lack of Confidence, and Frustration (see Table 3). Secondary themes identified deficiencies in communication, unprovided resources, and lack of knowledge on concussion policy (see Table 3), all combined to frame the experiences professors have had when faced with providing accommodations to their students.

Unaware of Policies

Participants were unaware whether their university had a concussion protocol or a RTL protocol to follow. Without an official policy or procedure in place, each experience in providing academic accommodations varied based on the student interactions, student requests, or course load at the time.

Unaware if a Policy Exists

Multiple professors were certain their university did not have an active RTL policy. When asked to explain the RTL policy at their university, Brandon and Emily echoed similar experiences. Brandon expressed, “I mean, I suppose we should have a policy, because I don’t think we have one. Or, at least, I never heard of one.” Emily: “If it exists, I’m not aware of it.” Furthermore, participants were unsure where to look for the policy, if one did exist. Adam shared: “I’m not aware of whether we have a return to learn policy. If it does exist, I don’t know if it’s in the student handbook, or the faculty handbook… We may, but I’m not aware of it.” While Janet expressed, “I am assuming that there is a policy that’s held by the Athletic Department? And again, that’s an assumption, so, we all know about assumptions and assuming things.”

Student-Driven Accommodation

Without any official policy or procedure put in place to be executed, academic accommodations were only implemented after students communicated with their professors. Students would talk with their professors directly, informing them of their injury and some of the accommodations they would need. Courtney recalled how she learned about her student’s injury and then how they determined accommodations:

I believe she came and told me. Yes, she came to class on Monday and told me what happened during the weekend. I remember her saying the screen time on her eyes would spark a migraine. So I said, “If you were to listen to something, can you take that information in?” And she said, “Yes, that doesn’t spark up a migraine.

Grace described how she works with students to determine accommodation levels, stating:

That’s where I say a lot of the time, I let the students lead. I don’t necessarily change my standards, but I can be flexible on due dates, and alternative ways of submitting things. But most of the time, I just let the student lead in letting me know what they need.If not directly from the student, a teammate, a member of the Athletic Department, a coach, or an athletic trainer could have been the one to tell the professor about the injury. Adam recanted the time he had to hear from the student’s teammate, stating, “Another student who was on the same sports team, told me that the student had a concussion, and that’s why they weren’t going to be able to do the labs or tests they had to do.” Grace recalled how she got an email from an athletic trainer, but it was forwarded to her by the student, saying, “And, like I said, this is my more normal experience. The student sent me a note, from the athletic trainer saying ‘this student had a concussion at practice yesterday.’”

Lack of Confidence

Lack of Confidence centered around participants’ level of assurance at knowing which accommodations to provide the students. Emily reinforced that she was confident to administer an academic accommodation if asked, but did not feel she had the skills, abilities, or means to recognize or determine which accommodations were needed or how they should be administered. She stated:

So, from zero to ten, my willingness to accommodate, eleven… But in terms of what specifically would address the issues of a concussion, I would say, No. I don’t know brain-wise what is best based on the science part.

Isaiah echoed a similar sentiment by saying:

Because I am not suited to provide accommodations according to my expertise. I don’t have expertise on that. And I don’t know what their cognitive functionality or compromises are… I don’t feel comfortable making a plan for a student with a concussion. I just don’t know what their capacity is when they come to me.

Frustration

Frustration was a significant emotion that continued to be woven within the responses of the participants. It was noted that respondents would answer questions with a level of exasperation or indignation. It was evident that components of their experiences with these cases carried negative emotions and frustration.

Level of Communication

Participants consistently expressed their frustration at the level of communication they receive between the different stakeholders of this injury. Brandon stated, “So in the context of our university here, I would like to have greater communication between the coaches, the faculty, and the students.” David went on to say, “I think a more streamlined connection between our accommodations and our athletics departments would probably be a huge step forward.”

Several recounted the lack of communication they received regarding the initial injury of the athlete. Isaiah and Kendall both unveiled their frustration with the amount of communication they wish would occur, with Isaiah commenting: “It’s been a week now since the accident, and he’s never shown up in the class. And I don’t know why. I’ve never received any updates on why this student cannot be in the class.”

Kendall added that:

It’s frustrating not to have that kind of communication with somebody, the coach, or an athletic trainer. It feels like if we are going to have athletes on campus, then there needs to be something that’s overseeing the communication between faculty members, athletics, and administration.

Others noted the lack of updates they receive on the student while they are trying to heal or even when the student is fully healed and can return to regular cognitive load. Emily contributed:

…as faculty, we need to be made aware. I’m not a medical doctor. I was finding myself needing to assess the continuation of her progress. And I felt like I couldn’t really do that. We [Faculty] need to be aware of where they are in the process.

Kendall noted her frustration by presenting a new process to solve the problem by saying:

I would just like to see a clear, defined ‘this is what happens’… You email all the professors with the checklist so they can see where they are in the process. Everybody gets notified, the student is aware, the faculty are aware, that the communication is there.

Foster described the ambiguity surrounding returning the student to full academic load and shared how these decisions have been made. He stated:

There really isn’t this meeting of ‘I’m good now’. It’s more of an organic, ‘Oh, now they are back’. There isn’t this ‘everything’s good now’ meeting or stamp of ‘Yeah, we’re back’ by any professional staff, athletics, or anything like that.

Some participants expressed their frustration with the lack of communicating what accommodations to provide the student based on their injury. Without knowing what to provide, it was very difficult for them to determine what was needed, prompting a desire for more communication on what accommodations to provide. Isaiah commented:

Yeah, I like that idea rather than trying to determine what to do. Because I did have a problem, as we were saying we are not doctors. I’m not here to determine or assess the situation. So, I would love to receive some kind of guidelines to work within that tells me what the students can and can’t do.

Beyond wanting instructions to navigate their situation, many participants revealed the lack of communication between other faculty or university staff created a barrier to the level of collaborative care of the student. Without structured communication between all relevant parties, professors were not privy to what other accommodations were being provided or how long accommodations needed to be extended. One student shared:

There’s no one to share information of what other classes, what other tests, or what other things is the student studying for… There’s nothing to navigate the whole breadth of what that student is trying to catch up on.

Grace recalls her struggle with returning a student to full cognitive load due to variability in the level of accommodations her student was receiving from other professors. She mentioned:

Part of it was this girl took a long time to catch up because other instructors weren’t giving her grace… there’s no coordination between any of her instructors. So, I took the brunt of it because I was being understanding. And I had to take a long time to catch her back up.

Lastly, it was expressed that the level of communication is a major problem that needs to be addressed, especially at a time when communication efforts are easy. Technological advancements have provided the means and opportunity to facilitate collaborative communication easily, it just needs to be prioritized and used appropriately. Foster stated:

I think the easiest thing would just be communication. I would just headline that as king, communication… it’s a simple process in my opinion. I know it feels brash, but it’s just creating one document. We have the Google system where it’s easy to create a Google form to notify every person involved of “this student-athlete was concussed. We’re working on it.”…There’s no excuse anymore, especially at a small school like ours, it’s so easily done. It’s just laziness if it’s not happening. It could be so easily done.

While Horace commented:

You know, generically, the technology will allow communication very easily for all of the professors for one student. It would be very easy to communicate. …you know, we have so much technology that we’re using now, and I keep coming back to that, but we have the ability, at least our institutions do. The technology is already there… Because communication seems to be a real issue here. The compassion, grace, understanding what students’ needs are, and providing accommodations for them, all of us are in favor of doing… But we just need the proper kind of communication to know how to provide that.

Lack of Support

The lack of support experienced by collegiate professors stemmed from a feeling of isolation when attempting to help students succeed. Professors echoed that they do not receive the support they need from athletics, other faculty, or university administration when faced with these situations. Without operational support, professors must rely solely on their students to provide instructions and information regarding their care. Also, although there is a base level of trust, the nature of their concussion leave professors questioning the reliability and trustworthiness of the information they receive. For example, Foster stated:

I ask them [the student-athlete], “Hey, is this everything?” Well, I’m asking a concussed person to remember everything. That’s just really dumb on my part. So, it’s not a distrust. It’s a need to go talk to someone aware of everything and fully confident to talk through it

Horace unveiled his frustration when trying to assist students when they have a concussion, saying:

I’ve had that happen with students who’ve come in, they are in a fog. And we can’t expect them to give us lucid, accurate accounting of what’s really happening with them, because they really don’t know. And that is part of the problem as well.

Lack of Resources

Not only have professors experienced isolation, but also a lack of resources to assist in decision-making. Professors reported that no information is given on RTL policies or the accommodations that would help their students. Emily added that at her university, there is a lack of literature disseminated or provided in a clear location to professors to help them in the decision-making process, saying, “If I had been able to sit down, or been provided information on concussions and the impact and stuff like that, it would have been helpful.” She went on to further add:

As professors, we’re just dealing with so many things we just don’t know. But if we’re aware of something that exists out there, if it was in our handbook, that would be really helpful. I can see a lot of need for it.

Foster added that although he is aware of a policy in athletics, he knows that this knowledge is not shared with faculty. Without knowledge getting extended to the faculty, professors feel illequipped to make accommodation decisions for their students and don’t know how to find the information they need to assist their decision-making. He also stated:

I know this exists because of my background, that there is a concussion protocol process. Other faculty aren’t aware of that… they aren’t aware that this protocol exists… So, I think, from a faculty side, we need to make them aware of those, that’d be big.

Grace added:

Even just some quick guidelines, in the moment, when you get that notification. I think it would be super helpful. Because I think that’s where I struggle. That’s where I say “I don’t know.” … And so just to get that information on the front end. Because I don’t feel like I have a good idea as to how to handle the concussions most of the time.

Discussion

This phenomenological study was conducted to investigate the experiences of collegiate professors in providing academic accommodations to their students who had suffered a concussion. Overall findings revealed an overarching desire for student success. Collegiate professors cared so greatly for their students to receive the care they needed while providing an opportunity to still be successful in their course. Although there is a desire for the student to be successful, it is opposed by the dichotomy that the rigor of the course cannot be compromised. Collegiate professors are, then, trying to balance providing an environment of success without minimizing, lowering, or compromising the learning outcomes of their courses. From the context of trying to maintain this balance, collegiate professors shared the frustrations that have manifested from their experience, the lack of confidence they have felt in these cases, and unveiled their struggles in not having, or not being aware, of policies and procedures to assist in the RTL process.

Frustrations

Frustrations manifested from several key sources: level of communication, lack of support, and lack of resources. Communication was deemed one of the biggest components that led to frustration as many professors expressed their dissent with the amount of communication they did, or did not, receive. Professors expressed how they are not communicated with about the student’s injury, are provided very minimal communication at the initial injury, and receive minimal communication through the care or completion of the RTL. This supports the findings by Welch Bacon et al. [24] who unveiled that stakeholder communication breakdown was a major barrier to the implementation of RTL in institutions, and Lyons et al [25] who discovered educators desire clearer and more frequent communication to assist them in accommodating students with a concussion. Stronger avenues for communication need to be established for professors to effectively collaborate with all members involved with the care of the student [5, 26]. Greater communication between professors, administrators, and members of the sports medicine team will increase the continuity of care and improve feelings of isolation and confusion experienced by professors.

A lack of resources and support was also presented as a major component causing contention. Professors feel siloed. They do not feel like they are provided with the knowledge, information, or means to successfully and confidently manage these cases. Frustration abounds when they do not feel they have the operational support or resources to answer the questions they have. They become completely reliant upon their prior knowledge or become subject to the honesty of the student relaying information to them. It has been previously reported that educators feel ill-equipped to implement RTL as they do not have prior training or expertise in the field [25, [27-30]. When compounding their lack of knowledge with a lack of resources or support when accommodating, it leaves the professor confused and frustrated, and leads to negative accommodation experiences [25]. It is for fear of these negative experiences that students report as major barriers for them seeking or accepting accommodations when suffering their concussion [20, 31]. Therefore, greater resources and administrative or university support were recommended to aid professors in positively navigating their experiences when they arise. The professors desired clearly defined guidelines for academic accommodations in an initial contact letter, policies and additional resources posted in the faculty handbook, and implementation of technological tools to assist in determining accommodations and enhance communication with administrators were all mentioned to help provide them with more resources and support to feel less isolated and more competent in providing care.

Lack of Confidence

College professors expressed they have adequate skills and abilities to administer academic accommodations when asked. Many of the professors advocated that the accommodations provided to students were helpful and needed to be successful in the course [19]. However, there is a prevailing lack of confidence in understanding which accommodations to provide the students. The variability in symptoms of concussions, and the variability in classroom instruction, left the professors underprepared and unable to determine what to provide and how long to provide it for. The lack of knowledge professors possess and the lack of training they receive are direct factors causing barriers for students to seek accommodations [20, 27, 29, 30]. Without the skills or knowledge to confidently manage their cases, professors are not confident they can appropriately recognize what is required for the student and feel very overwhelmed and apprehensive about administering academic accommodations successfully [30].

Lack of Policies

Across both universities, college professors indicated they were unaware if any policies existed regarding concussions or RTL. While they were willing to admit that policies or procedures could exist somewhere, it was not a point of emphasis nor was it made known to them. Many expressed that they could look in various places to try and find a policy; however, they would be shocked if they were to find it there. This perception is not unlike the perceptions held by other professors and educators studied in the literature, as studies have unveiled either institutions have not created an RTL or they do not include collegiate professors and make them privy to the RTL process [16, 25, 32, 33]. Without a written, acknowledged policy in place, professors are unaware of their role in concussion management or what should be provided to their students [25]. Without a policy to consult, professors are dependent on student information to drive accommodation decisions yielding inconsistent care. The variability in care causes disparities in the accommodations provided from course to course, the duration of accommodations available, and differences from student to student. The incongruency creates ambiguity when providing care, and can lead to negative outcomes for students and negative experiences for professors [25, 30].

Institutional Recommendations

Universities should evaluate the resources they offer professors to help them support their students while still upholding and maintaining the rigor of their courses. Faculty support, collaboration, the introduction of policies, educational resources disseminated, and avenues of greater communication should all be invested in to enhance the experiences of their professors. Universities should evaluate their RTL policy and use supporting roles to create a cohesive plan [5, 34]. Utilizing athletic trainers, faculty athletics representatives, disability services, or other members of the sports medicine team will enhance the quality of the RTL and the quality of service provided to students [5, 35]. Once created, provide it to the faculty, staff, athletic departments, and students to be aware of the process that is to be followed. After it has been presented to all relevant stakeholders, housing the policy in a place easily found where faculty can easily defer to it when needed. Maximizing technologies like email, learning management systems, or cloud-based accounts can enhance the level of communication university-wide and provide better avenues for collaborative care for students when they have suffered a concussion.

Limitations

This phenomenological study was conducted at two private universities located on the West coast, thus potentially affecting the generalizability of the study. Additional studies should be completed to unveil the experiences of collegiate professors in other settings or other regions. Although additional steps, including a reflexivity journal, were taken to mitigate the influence of bias on our results, it is still a limitation of this study and may have influenced the results.

Conclusions

Concussions are traumatic brain injuries that will cause several signs and symptoms affecting a student’s ability to be successful in the classroom. To assist these students, academic accommodations are traditionally provided to combat their symptoms until they are ready for a full academic load. College professors are depended on to support their students and provide them with the accommodations they need; however, professors have not had positive experiences when called upon to assist. College professors are not presented with or made aware of policies and procedures that would assist in providing accommodations to their students. Without resources or support, professors do not feel confident in their abilities to decide which accommodations these students need to be successful. This has led to overall frustration with the lack of support and lack of communication needed to make these instances more successful. An investment by universities into creating effective policies, educating faculty in those policies, and providing ample avenues for constant communication would lead to more positive outcomes and enhance student care when they suffer a concussion.

Competing interests:

The authors of this research declare no competing interest regarding this study.

References

Broglio, S. P., Cantu, R. C., Gioia, G. A., Guskiewicz, K. M., Kutcher, J., Palm, M., & McLeod, T. C. V. (2014). National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: Management of sport concussion. Journal of Athletic Training, 49(2), 245– 265.View

Leddy, J., Baker, J., & Willer, B. (2016). Active Rehabilitation of Concussion and Post-concussion Syndrome. Physical Medicine Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 27, 437–454.View

McCrory, P., Meeuwisse, W. H., Aubry, M., & Cantu, B. (n.d.). Consensus statement on concussion in sport: The 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012. Consensus Statement, 12.View

Thomas, D. G., Apps, J. N., Hoffmann, R. G., McCrea, M., & Hammeke, T. (2015). Benefits of Strict Rest After Acute Concussion: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatrics, 135(2), 213–223.View

Hall, E. E., Ketcham, C. J., Crenshaw, C. R., Baker, M. H., McConnell, J. M., & Patel, K. (2015). Concussion Management in Collegiate Student-Athletes: Return-To-Academics Recommendations. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 25(3), 291.View

Hutchison, M. G., Mainwaring, L., Senthinathan, A., Churchill, N., Thomas, S., & Richards, D. (2017). Psychological and Physiological Markers of Stress in Concussed Athletes Across Recovery Milestones. The Journal Of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 32(3), E38–E48.View

Johnson, B. D., O’Leary, M. C., McBryde, M., Sackett, J. R., Schlader, Z. J., & Leddy, J. J. (2018). Face cooling exposes cardiac parasympathetic and sympathetic dysfunction in recently concussed college athletes. Physiological Reports, 6(9), e13694–e13694.View

Korobeynikov, G., Korobeynikova, L., Potop, V., Nikonorov, D., Semenenko, V., Dakal, N., &Mischuk, D. (2018). Heart rate variability system in elite athletes with different levels of stress resistance. Journal of Physical Education & Sport, 18(2), 550–554.View

Mirow, S., Wilson, S. H., Weaver, L. K., Churchill, S., Deru, K., & Lindblad, A. S. (2016). Linear analysis of heart rate variability in post-concussive syndrome. Undersea & Hyperbaric Medicine: Journal Of The Undersea And Hyperbaric Medical Society, Inc, 43(5), 531–547.

Bacon, C. E. W., Cohen, G. W., Kay, M. C., Tierney, D. K., & McLeod, T. C. V. (2018). Athletic Trainers’ Perceived Challenges Toward Comprehensive Concussion Management in the Secondary School Setting. International Journal of Athletic Therapy & Training, 23(1), 33–41.

Bryan, M. A., Rowhani-Rahbar, A., Comstock, R. D., Rivara, F., & on behalf of the Seattle Sports Concussion Research Collaborative. (2016). Sports- and Recreation-Related Concussions in US Youth. Pediatrics, 138(1), e20154635.View

Llewellyn, T., Burdette, G. T., Joyner, A. B., & Buckley, T. A. (2014). Concussion Reporting Rates at the Conclusion of an Intercollegiate Athletic Career. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 24(1), 76–79.

McAvoy, K., Eagan-Johnson, B., & Halstead, M. (2018). Return to learn: Transitioning to school and through ascending levels of academic support for students following a concussion. Neurorehabilitation, 42(3), 325–330.View

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). (n.d.). Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.View

Buckley, T. A., Baugh, C. M., Meehan, W. P., & DiFabio, M. S. (2017). Concussion Management Plan Compliance: A Study of NCAA Power 5 Conference Schools. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 5(4), 2325967117702606.View

Williamson, C. L., Norte, G. E., Broshek, D. K., Hart, J. M., & Resch, J. E. (2018). Return to Learn After Sport-Related Concussion: A Survey of Secondary School and Collegiate Athletic Trainers. Journal of Athletic Training, 53(10), 990– 1003.View

Iadevaia, C., Roiger, T., & Zwart, M. B. (2015). Qualitative Examination of Adolescent Health-Related Quality of Life at 1 Year Postconcussion. Journal of Athletic Training, 50(11), 1182–1189.View

Moran, L. M., Taylor, H. G., Rusin, J., Bangert, B., Dietrich, A., Nuss, K. E., Wright, M., Minich, N., & Yeates, K. O. (2012). Quality of Life in Pediatric Mild Traumatic Brain Injury and its Relationship to Postconcussive Symptoms. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 37(7), 736–744.View

Childers, C., & Hux, K. (2016). Invisible Injuries: The Experiences of College Students with Histories of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 29(4), 389–405.View

Hong, B. S. S. (2015). Qualitative Analysis of the Barriers College Students With Disabilities Experience in Higher Education. Journal of College Student Development, 56(3), 209.View

Hux, K., Bush, E., Zickefoose, S., Holmberg, M., Henderson, A., & Simanek, G. (2010). Exploring the study skills and accommodations used by college student survivors of traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 24(1), 13–26.View

Runyon, L. M., Welch Bacon, C. E., Neil, E. R., & Eberman, L. E. (2020). Understanding the Athletic Trainer’s Role in the Return-to-Learn Process at National Collegiate Athletic Association Division II and III Institutions. Journal of Athletic Training, 55(4), 365–375.View

Creswell, J. W. (2016). 30 Essential Skills for the Qualitative Researcher. Sage Publications.View

Welch Bacon, C. E., Erickson, C. D., Kay, M. C., Weber, M. L., &Valovich McLeod, T. C. (2017). School nurses’ perceptions and experiences with an interprofessional concussion management team in the secondary school setting. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 31(6), 725–733.View

Lyons, V. H., Moore, M., Guiney, R., Ayyagari, R. C., Thompson, L., Rivara, F. P., Fleming, R., Crawley, D., Harper, D., & Vavilala, M. S. (2017). Strategies to Address Unmet Needs and Facilitate Return to Learn Guideline Adoption Following Concussion. The Journal Of School Health, 87(6), 416–426.View

McGrath, N. (2010). Supporting the Student-Athlete’s Return to the Classroom After a Sport-Related Concussion. Journal of Athletic Training, 45(5), 492–498.View

Carzoo, S. A., Young, J. A., Pommeling, T. L., & Cuff, S. C. (2015). An Evaluation of Secondary School Educators’ Knowledge of Academic Concussion Management Before and After a Didactic Presentation. Athletic Training & Sports Health Care: The Journal for the Practicing Clinician, 7(4), 144–149.View

Glang, A. E., McCart, M., Slocumb, J., Gau, J. M., Davies, S. C., Gomez, D., & Beck, L. (2019). Preliminary Efficacy of Online Traumatic Brain Injury Professional Development for Educators: An Exploratory Randomized Clinical Trial. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 2, 77.View

McCart, M., Glang, A. E., Slocumb, J., Gau, J., Beck, L., & Gomez, D. (2020). A quasi-experimental study examining the effects of online traumatic brain injury professional development on educator knowledge, application, and efficacy in a practitioner setting. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(17), 2430–2436.View

Romm, K. E., Ambegaonkar, J. P., Caswell, A. M., Parham, C., Cortes, N. E., Kerr, Z., Broshek, D. K., & Caswell, S. V. (2018). Schoolteachers’ and Administrators’ Perceptions of Concussion Management and Implementation of Return-to-Learn Guideline. The Journal of School Health, 88(11), 813–820.View

Cover, R., Roiger, T., & Zwart, M. B. (2018). The Lived Experiences of Retired Collegiate Athletes With a History of 1 or More Concussions. Journal of Athletic Training, 53(7), 646–656.View

Dreer, L. E., Crowley, M. T., Cash, A., O’Neill, J. A., & Cox, M. K. (2017). Examination of Teacher Knowledge, Dissemination Preferences, and Classroom Management of Student Concussions: Implications for Return-to-Learn Protocols. Health Promotion Practice, 18(3), 428–436.View

Kerr, Z. Y., Register-Mihalik, J. K., Kroshus, E., Baugh, C. M., & Marshall, S. W. (2016). Motivations Associated With Nondisclosure of Self-Reported Concussions in Former Collegiate Athletes. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(1), 220–225.View

Buckley, T. A., Burdette, G., & Kelly, K. (2015). Concussion- Management Practice Patterns of National Collegiate Athletic Association Division II and III Athletic Trainers: How the Other Half Lives. Journal of Athletic Training, 50(8), 879–888.View

Heyer, G. L., Weber, K. D., Rose, S. C., Perkins, S. Q., &Schmittauer, C. E. (2015). High School Principals’ Resources, Knowledge, and Practices regarding the Returning Student with Concussion. The Journal of Pediatrics, 166(3), 594-599.e7.View